The previous post in this series confirmed the MMT assertion the deficit creates the funds (in Bank Reserves) that are used by the finance sector to buy Treasury Bonds. Therefore, leaving aside the foreign sector and countries like those in the EU that don’t issue their own currency, there is never a problem with a government selling bonds to cover a deficit: their purchase is actually a favourable asset swap for the finance sector, exchanging non-income-earning Reserves for income-earning Bonds.

Though this is still a very simple and stylized model, it lets us do something we can’t do in the real world: separate out the economic impact of the government undertaking a policy from the private sector’s reaction to that policy. This allows us to isolate causal factors when there is more than one cause at play. That’s vitally necessary to be able to interpret historical data on whether running deficits is a good idea or not, because (leaving aside the foreign sector) there are two ways to create money: by the government running a deficit, or by the banks lending out more than they get back in repayments.

Historical Deficits & Surpluses

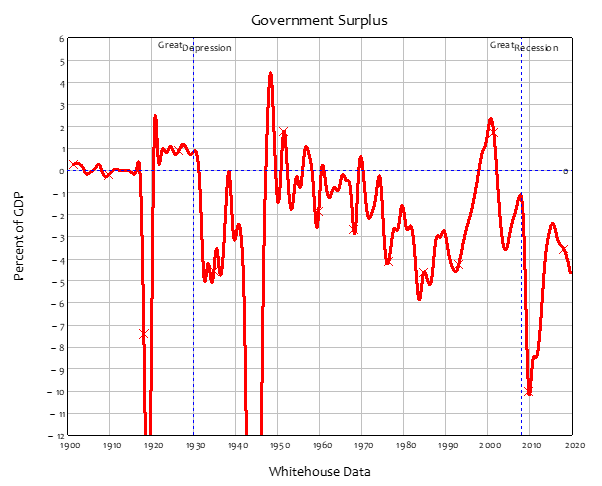

The US government has, on average over the last 120 years, run a deficit equivalent to 2.3% of GDP. The post-WWII average has been -2.5%—see Figure 1. The peak deficit occurred during WWII, at almost 26% of GDP.

Figure 1: US Government surplus since 1900

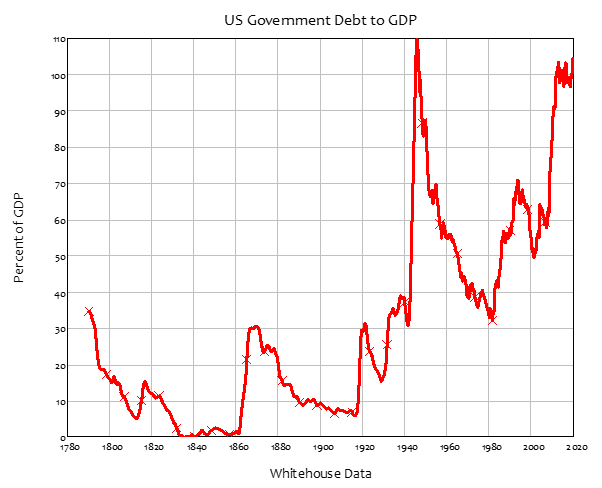

These deficits, and some surpluses—most notably, the decade of the 1920s, and the late Clinton to early Bush II years—have led to the Government debt to GDP ratio varying substantially over time—see Figure 2.

Figure 2: The US Government’s debt to GDP ratio since 1790

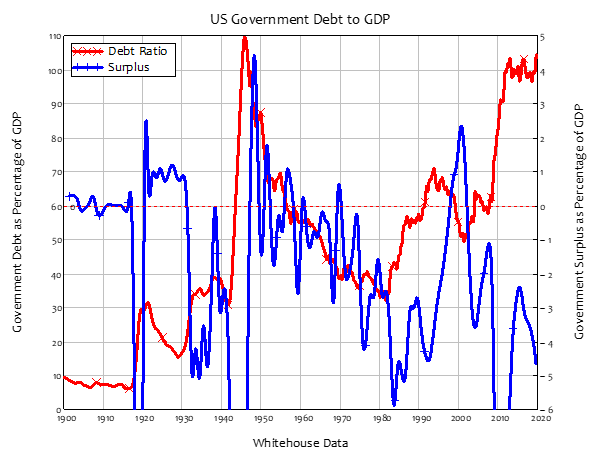

The relationship between deficits and the government debt to GDP ratio is not straightforward: there are substantial periods where the government is running a deficit and the debt ratio is falling. The clearest example of this is between 1950 and 1980, when there were only brief periods of surplus and the deficit averaged 1% of GDP; the government debt ratio fell from 87% of GDP to 34% of GDP over that time. This period includes the so-called “Golden Age of Capitalism” between the start of the 1950s and the middle of the 1970s, when GDP growth was high, and unemployment and inflation were low.

Figure 3: Government Debt Ratio vs Government Surplus

But there were also “Gilded Ages”—like the 1920s and the Clinton Years till 9/11—when the government ran a surplus and the economy boomed. During these periods, surpluses were lauded as a sign of true economic success.

This was President Calvin Coolidge’s position. He maintained a 1% of GDP surplus throughout his term, and in his final State of the Union speech in December 1928, he lauded his surplus as the cause of the prosperity of the 1920s:

No Congress of the United States ever assembled, on surveying the state of the Union, has met with a more pleasing prospect than that which appears at the present time…

We have substituted for the vicious circle of increasing expenditures, increasing tax rates, and diminishing profits the charmed circle of diminishing expenditures, diminishing tax rates, and increasing profits.

Four times we have made a drastic revision of our internal revenue system, abolishing many taxes and substantially reducing almost all others. Each time the resulting stimulation to business has so increased taxable incomes and profits that a surplus has been produced. One-third of the national debt has been paid, while much of the other two-thirds has been refunded at lower rates, and these savings of interest and constant economies have enabled us to repeat the satisfying process of more tax reductions. Under this sound and healthful encouragement the national income has increased nearly 50 per cent, until it is estimated to stand well over $90,000,000,000. It has been a method which has performed the seeming miracle of leaving a much greater percentage of earnings in the hands of the taxpayers with scarcely any diminution of the Government revenue. That is constructive economy in the highest degree. It is the corner stone of prosperity. It should not fail to be continued. {Coolidge, 1928 #6057}

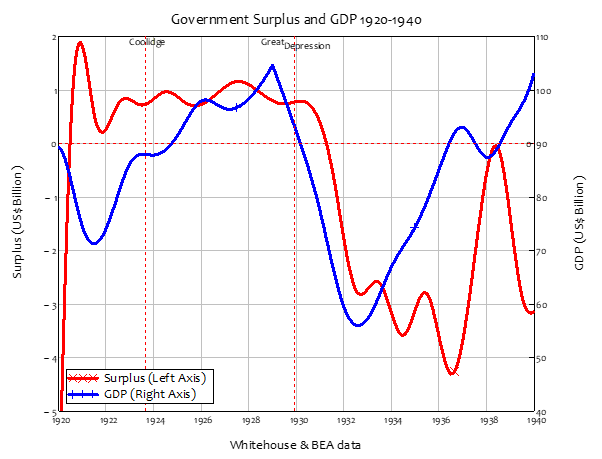

Looking at the data, it appears that Coolidge had a point: GDP rose from $70 billion to over $100 billion across the 1920s, as his government maintained a surplus of about $1 billion per year. Did the surplus cause the “Roaring Twenties” boom? In a classic case of “correlation is not causation”, superficially it seems that the decline into a deficit caused the Great Depression.

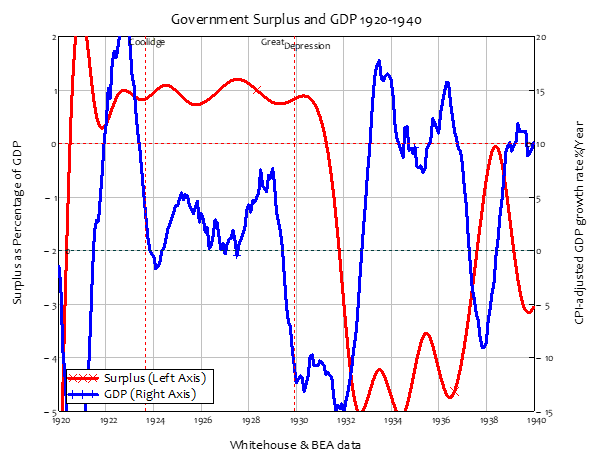

Figure 4: Government surplus and GDP 1920-1940

However, the decline in the growth rate, from 7% to minus 10%, preceded the change from surplus to deficit (see Figure 5), so perhaps the Great Depression caused the change from surplus to deficit. Also, after the original crash between 1920 and 1932, the rate of real economic growth was extremely high between 1933 and 1936, exceeding 10% per annum when the deficit was 5% of GDP. A return to a balanced budget (if not quite a surplus) between 1937 and 1938 coincided with a collapse in economic growth, from over 15% per annum in 1936 to almost minus 10% in 1938.

Figure 5: Surplus as % of GDP versus real GDP growth rate

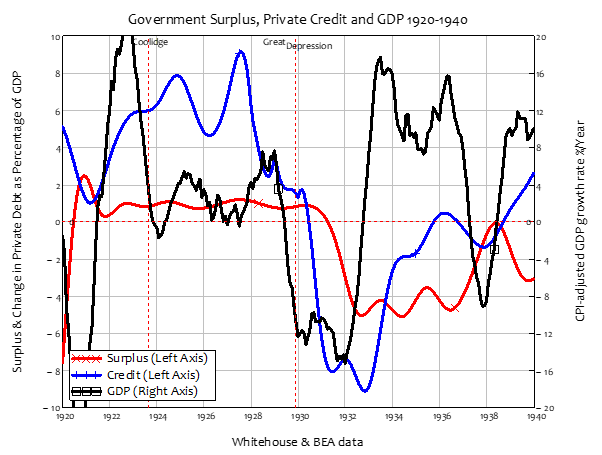

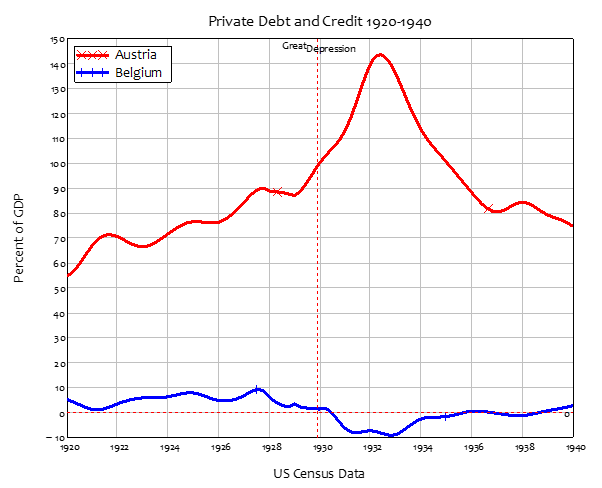

This analysis ignores the factor that (following Irving Fisher and Hyman Minsky) I focus upon as the main cause of capitalism’s booms and busts: private credit. As Figure 6 shows, credit was positive during the 1920s, and negative during the 1930s—matching much more closely the pattern of GDP change. It was also much bigger than the government surplus or deficit: credit was as high as 9% of GDP in 1929, versus a surplus of 1%; and it was as low as -9% of GDP in 1933, versus a deficit of 5%.

Figure 6: Surplus, Credit, and Change in GDP

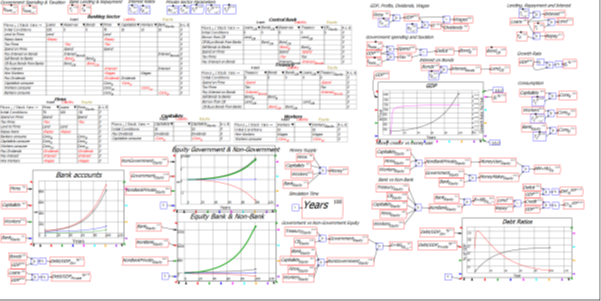

Let’s cut through this historical confusion with some simple simulations using this model in which we can separate out periods of deficit and surplus from periods of private sector leveraging and deleveraging.

Phase 1: A deficit for 100 years

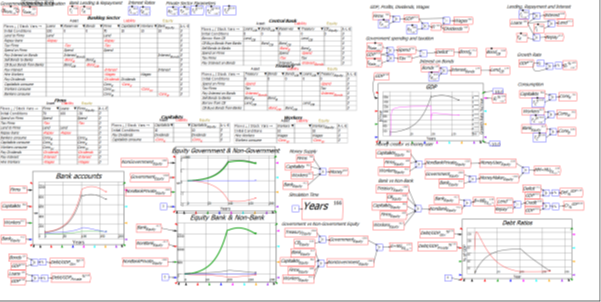

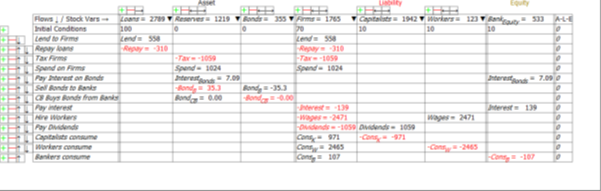

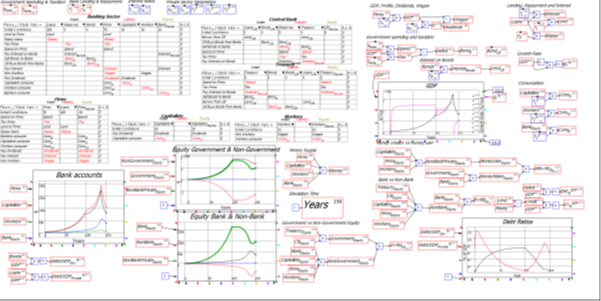

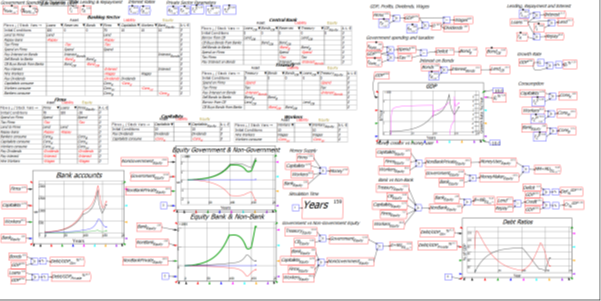

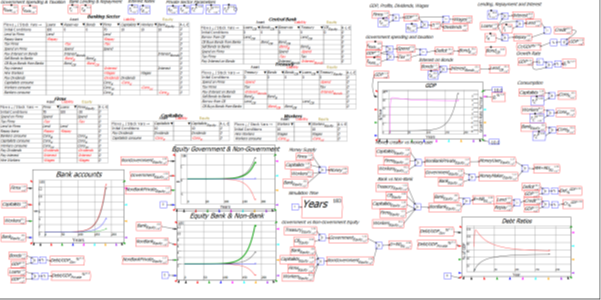

The first simulation has a deficit of 2.5% of GDP—roughly equal to the average US government deficit since 1900—for 100 years. Spending is 32.5% of GDP and taxation is 30% of GDP. The Treasury sells Treasury Bonds to the Banks, and pays interest on those bonds to the Banks by borrowing from the Central Bank.

Figure 7: Deficit for 100 Years

The deficit is expansionary, and pushes the whole private sector—Firms, Capitalists and Workers as well as Banks—into positive equity, to the tune of $1,734. This positive equity is of course precisely equal in magnitude to the negative equity of the Treasury of $1,734.

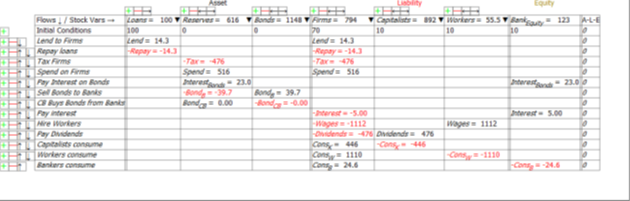

At the end of this part of the simulation, the total assets of the banking sector are $1,834, backing an identical amount of money in the bank accounts of the non-bank private sector plus the banking sector’s equity. This is split between $100 in private debt (of the Firm sector), $616 in Reserves created entirely by the interest being paid on Bonds, and $1,148 in Bonds, created entirely by the government deficits.

Because there is no private sector borrowing, the private sector debt ratio also falls, from 70% of GDP at the beginning of the simulation to 6.3% by the end, as GDP rises from $140 per year to $1,588 at the end. Because the Treasury is selling Treasury Bonds to match the deficit and maintain its account at the Central Bank at a $0 balance, the ratio to GDP of Treasury Bonds owned by the Banking Sector rises from zero to 72% of GDP—at which point the “deficit hawks” are likely to intervene and insist that the government “gets its books in order” by running a surplus.

Figure 8: Banking sector’s books after 100 years of a 2.5% of GDP Deficit

Phase 2: A 1% of GDP surplus until Government Debt hits 10% of GDP

In this next phase, the government runs a 1% of GDP surplus by reducing spending to 29% of GDP. The immediate effect of this surplus is a slowdown in the rate of growth of GDP, from 4% p.a. to initially -2%. The growth rate bounces back for a while, but ultimately turns negative, and by the time the Government debt ratio has hit the 10% of GDP target (after 64 years), GDP has fallen from $1,588 per year to $1,418 per year.

Figure 9: A 1% of GDP surplus until government debr ratio hits 10%

The government’s debt level—the ratio to GDP of Treasury Bonds owned by the Banking sector—has fallen from 72% of GDP ($1,148/$1,1588) to 10% ($144/$1,430), as intended. However, the scale of the government’s negative equity has barely shifted, from $1,734 to $1,581. The reason is that a substantial part of the money that was created in Phase 1 was via interest payments on Bonds, which were financed by borrowing from the Central Bank. Even though Bonds owned by the Banks were declining at the rate of 1% of GDP per year, the interest on the outstanding debt remained high initially. These interest payments created money, countering the destruction of money by the surplus. The momentum of this plunged towards the end, hence the rate of decline of GDP increased.

The same effect applies with private sector equity, which reaches a peak when the additions to private sector equity from interest on Treasury Bonds is matched by the cancellation of bonds by the surplus. Then it falls as the scale of the government’s negative equity also falls. A surplus thus depresses economic activity, and reduces private sector equity.

But that’s not what Calvin Coolidge saw, and claimed: he claimed that a surplus causes the economy to boom, not slump. What was he, and this simulation, missing?

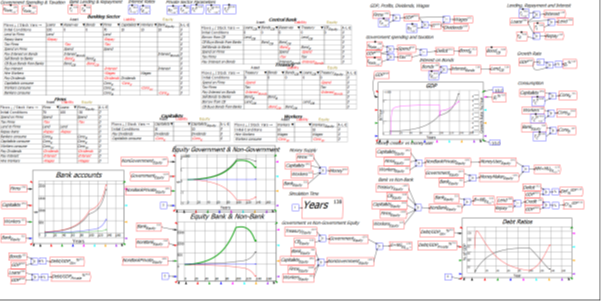

Phase 3: A surplus and Private sector borrowing

It, and Calvin Coolidge, missed the private sector borrowing. This simulation starts from the same point as Phase 2, but as well as the government running a 1% of GDP surplus, there is also net private sector borrowing as the time constant on lending falls to 5 years and that for repayment rises to 9 years. Credit is as high as 11% of GDP.

Figure 10: A surplus and private sector borrowing

Here the economic performance appears much better: GDP growth is sustained, and by the time the government debt ratio hits the target of 10% of GDP—after a mere 38 years in this simulation versus 64 year in the surplus-only case—GDP has risen from $1,588 per year to $3,529—a total boom.

However, because this was a boom financed by the firm sector borrowing money from the banks, by the end of it, the private debt to GDP ratio has risen from 6% to 79% of GDP. This is a bigger rise in private debt that occurred during the 1920s—and then abruptly went into reverse in 1920 (see Figure 11).

Figure 11: Private sector debt and credit (change in private debt per year) 1920-1940

Figure 12: The Banking sector’s books after 38 years of a 1% of GDP surplus and private sector borrowing.

What happens to the economy in this model if the private sector switches from borrowing to deleveraging while the government is still running a surplus?

Phase 4: Government surplus and private sector deleveraging

The answer, in so many words, is a Depression. With both the government surplus and private sector deleveraging taking money out of the economy, GDP plunges, from $3,529 when deleveraging began to $1614 just 12 years later.

Figure 13: The private sector switches from borrowing to deleveraging

What happens if, as occurred during the 1930s, the government switches from a 1% of GDP surplus to a 5% of GDP deficit, while the private sector continues to de-lever?

The result is a return to growth, as the deficit counteracts the reduction in the money supply caused by private sector deleveraging.

Figure 14: Government switches from Coolidge surplus to Roosevelt Deficit

Phase 0: What should be done?

I hope the previous simulations have clarified that deficits are indeed “unsustainable, irresponsible, and dangerous”, as Representative Hern’s motion puts it. The question is though, “which deficits?”. The clearly dangerous deficit is the private sector’s. The government can sustain deficits and accumulate substantial negative equity because it owns its own bank. The private sector cannot sustain deficits for a substantial period of time, because it doesn’t. Since one sector’s negative equity is the rest of society’s positive equity, the safe situation is for the government to have negative equity and the private sector to have positive equity.

It is possible for this to occur with the government running a deficit and the non-bank private sector borrowing from the banks at the same time. This final simulation shows the impact of a sustained government deficit of 2.5% of GDP—roughly the average for the USA for the last 120 years—and the private sector borrowing with a 7-year time constant for lending and 11 for repayment. This results in a nominal rate of growth of 5.25% p.a., a private debt ratio of 57.5% of GDP and a government debt ratio of 47.5%. That is the combination to which we should aspire, in our current monetary regime.

Figure 15: Deficits and limited credit, the ideal situation

Conclusion

The obsession politicians have with running a government surplus results from a partial perspective on the monetary system. With a holistic view, the real danger is the private sector’s deficit—which is the mirror image of the government’s. The best situation for the long term is to enable the private sector to sustain a surplus, which requires that the government sustains a deficit. This is possible for the government because, with a Treasury, a Central Bank, and a fiat currency, the Treasury can sustain and finance its negative equity indefinitely (leaving aside what happens on the external account for now).

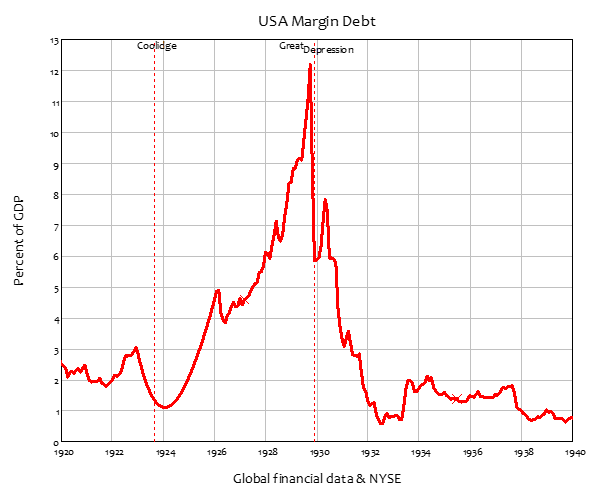

If the government instead becomes obsessed with achieving positive equity itself, then the private sector is pushed towards negative equity. The private sector response to this can be to gamble on financial assets: to borrow from banks and take levered positions in assets like property and shares. I haven’t included these factors in this simple model, but it is notable that the two periods where the US Government ran a surplus coincided with the two biggest stock market bubbles in American history, and the aftermath were its two deepest downturns (before Covid).

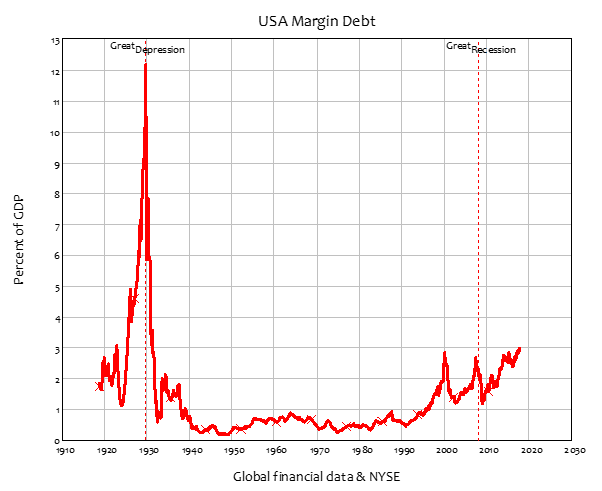

The scale of speculative borrowing when Coolidge was lauding his government’s surplus is staggering: margin debt rose from about 1% of GDP when he came to office to over 12% by the time of the 1929 Crash. It plunged even faster than it rose in the aftermath, to bottom at ½% of GDP in 1933. During the post-WWII period, it remained well below 1% of GDP until the Clinton administration came to power—obsessed, as Coolidge was, with achieving a government surplus.

Figure 16: When governments run surpluses, the private sector gambles

Correlation is not causation, but once again, the level of margin debt rose, from ½% of GDP in 1992 to the Triple Peaks of 2000, 2007, and … now (the data is incomplete because of changes in how it is recorded—whoever designed the latest data set at https://www.finra.org/investors/learn-to-invest/advanced-investing/margin-statistics needs to do some basic courses in data management!).

Figure 17: Margin debt over the long term

The bottom line of this set of posts is that we have to think about finances in an integrated manner, and not just focus upon one component, as “deficit hawks” like Hern do. With an integrated perspective, the sensible conclusion is the one MMT reaches: that the government should run deficits and be in negative equity, to enable the private sector to run surpluses and be in positive equity. Periods of apparent prosperity that coincided with the surpluses of the Coolidge and Clinton eras were the result of private sector levered speculation by a private sector that was experiencing (identical) deficits at the time. Rather than “saving for a rainy day”, these government surpluses helped set off speculative bubbles whose later crashes caused the greatest economic downturns in America’s pre-Covid history.

Private sector deficits as “unsustainable, irresponsible, and dangerous”. Public sector deficits are sustainable, responsible (subject to their impact on inflation and the balance of trade), and safe. It’s time for the “Deficit Hawks” to worry about private sector deficits, not the public sector deficit.

9 thoughts on “The Mathematical Model of Modern Monetary Theory 3”

Comments are closed.