As I write these words, Spain is suffering from its second wave of Covid-19, and it ranks 7th in the world for Covid-19 cases, when its rank in world population is far lower. It has, and is, experiencing more than its fair share of pain from the novel coronavirus.

Spain suffered far more than its fair share of pain during the Global Financial Crisis too. There is now a terrible danger that these two crises will compound each other, because neither Spain nor the rest of the world had truly recovered from the financial crisis when Covid-19 began.

I use the USA for most of my examples in this book, but in many ways Spain is a textbook example of the economic forces that caused the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), and how conventional economic thinking—epitomized most dramatically in the European Union’s limits on government debt and government deficits—helped cause the crisis, and made its impact even worse.

The data on Spain’s crisis and its bungled aftermath are so obvious that you might wonder why the thesis I defend in this book—that economic crises are caused not by government debt, but by private debt—is not the conventional wisdom. The role of Euro in triggering the boom in private debt, and thus making a crisis more likely, is also obvious. After an exciting first eight years, the Euro and its “Growth and Stability Pact” have led to contraction and instability.

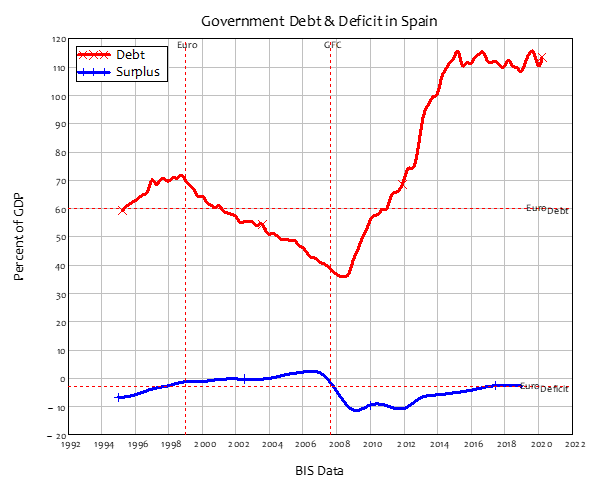

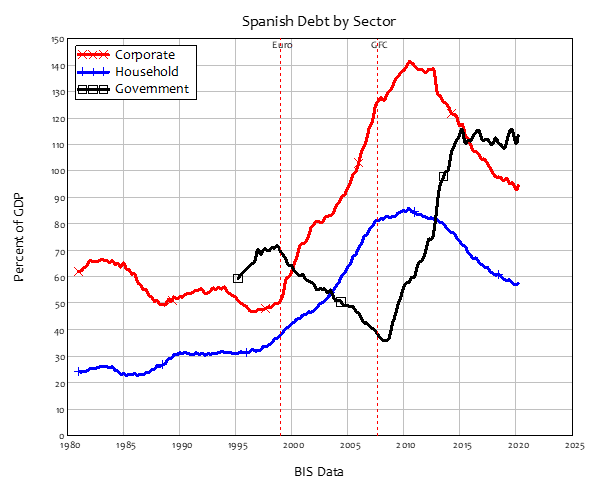

Much was made of Spain’s success in meeting the Growth and Stability Pact’s target of government debt being below 60% of GDP. Government debt was 70% of GDP when the Euro commenced in 1999, and it fell to a low of 35% of GDP by mid-2008. It was almost the only country in the Euro to meet and exceed both of the Euro’s policy targets: a government debt level of less than 60% of GDP, and a deficit of less than 3% of GDP. In fact, it exceeded the deficit target handsomely, running not a merely a small deficit, but a substantial surplus between 2004 and the crisis, peaking at 2.5% of GDP in mid-2006—see Figure 1.

If the Euro’s rules had the effect they were intended to have, this should have meant that Spain was less likely to experience a crisis, and well prepared to handle it if one did occur. This proved to be the opposite of the truth.

Figure 1

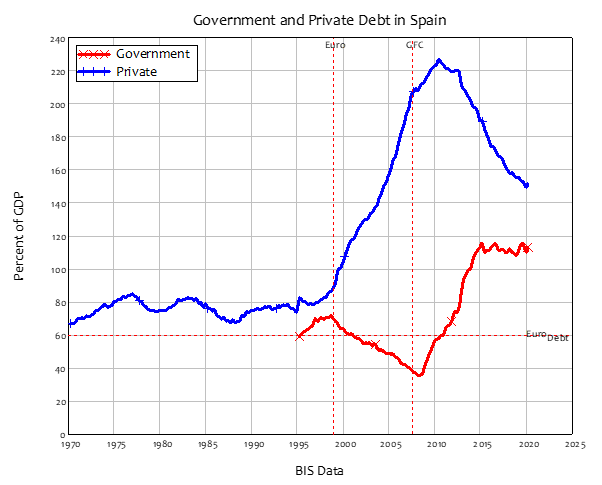

The reason is starkly evident in Figure 2: while Spain was lauded for halving its level of Government debt, across the same time span, private debt almost trebled—and throughout, it dwarfed government debt. Private debt had no trend before the introduction of the Euro: it was 67% of GDP in 1970, rose as high as 85% in 1977, but by the start of the Euro, it had risen not at all: it was also 85% of GDP in 1999.

However, from the introduction of the Euro until 2010, it rose far more rapidly than government debt fell: as government debt fell by 35% of GDP, private debt rose by 140%.

Figure 2: Spanish Debt Levels

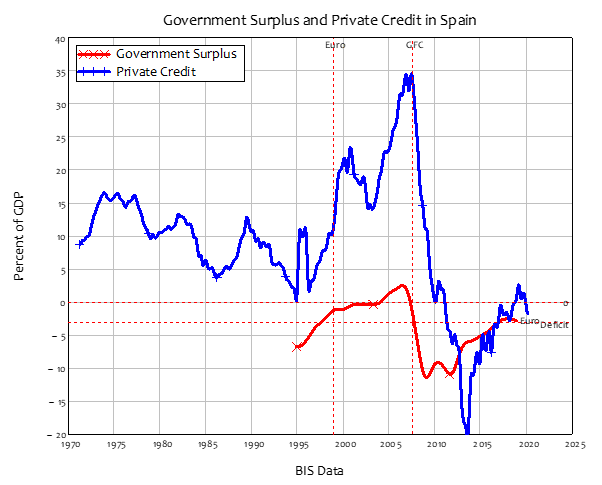

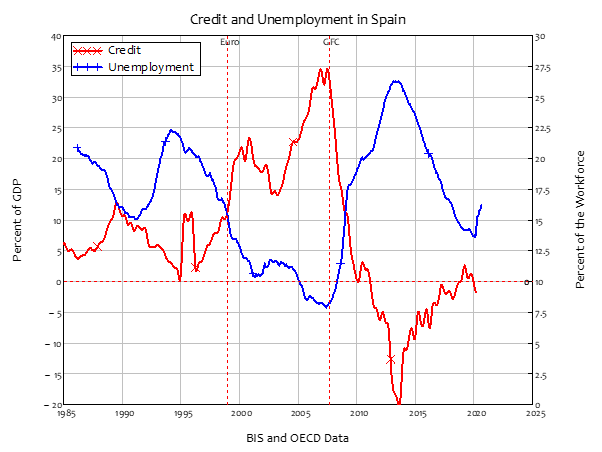

As I explain in this book, private debt drives economic performance, because the change in private debt—which I call credit, using the terminology of accounting—is a significant, and by far the most volatile, source of aggregate demand. It is therefore the dominant determinant of whether the economy will be in a boom or in a slump. And a credit-driven boom will contain the seeds of its own destruction in a crash, as I explain in this book.

While the Spanish government sector did what conventional wisdom regards as the right thing—reducing its debt by “living within its means”—the Spanish private sector did the opposite. It spent far more than it earned, and made up the difference with credit. This caused a credit-based boom in aggregate demand, which was a major reason why the government could run a surplus of as much as 2.5% of GDP per year at the same time. The government mistakenly attributed the economy’s strong performance in 2000-2007 to its surplus, but the real source of Spain’s boom was the growth of credit, from zero in 1995, to 10% of GDP when the Euro began, to a peak of 35% of GDP in 2008—almost 15 times the size of the government’s surplus.

Figure 3

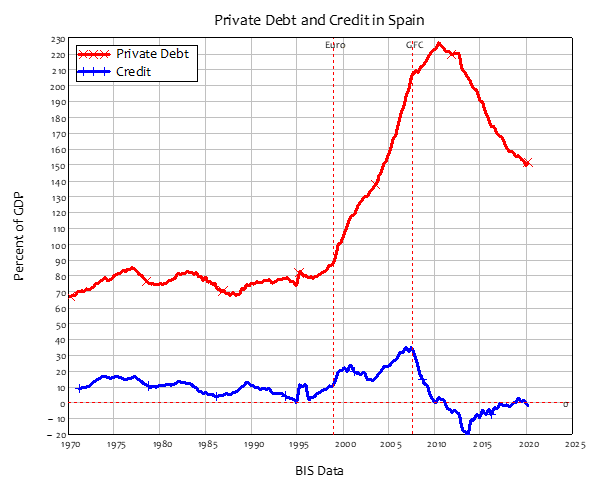

That huge credit-debt-driven stimulus to demand came at a price: a huge increase in Spain’s private debt, from 80% of GDP when the Euro commenced, to 210% when the financial crisis began—see Figure 4.

Figure 4

Both the household and corporate sector indulged in the debt bubble—though the impact of the Euro was more marked on bank lending to the corporate sector than to households. The household sector doubled its debt level from the start of the Euro till the crisis, while corporate borrowing almost trebled.

Figure 5

The crisis began when credit started falling—a pattern which was repeated across the world, but was extremely obvious in Spain. When credit goes up, unemployment goes down, and vice versa, as Figure 6 illustrates.

Figure 6

You might wonder, if the relationship is this strong and this obvious, the why did the government do nothing about it?

It is largely because their economic advisors, who are trained in mainstream economics, learn a model of banking in which credit plays no significant role in macroeconomics. That model, known as “Loanable Funds”, is technically false, as the Bank of England explained in 2014 (Michael McLeay et al., 2014). A false theory can play the role of blinkers on a horse, stopping you from looking at data that contradicts it, like Figure 6. That data makes it abundantly clear that the mainstream theory is wrong—but the mainstream didn’t pay any attention to that data before the GFC, and it hasn’t altered its model of banking since. Mainstream economics textbooks continue to teach the same false model of banking, even after being told, not only by the Bank of England but also by the Bundesbank (Deutsche Bundesbank, 2017), that this model is wrong.

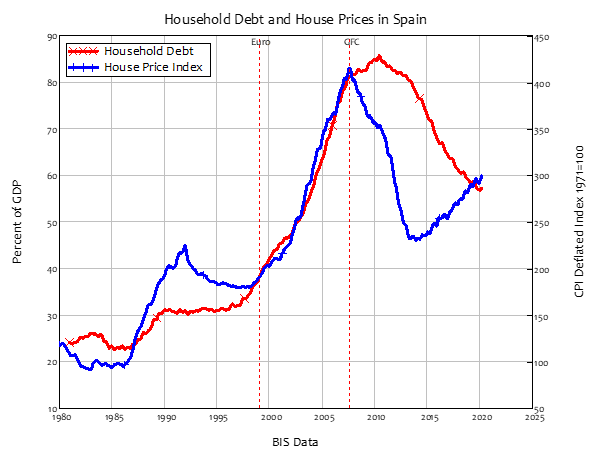

What even mainstream thinkers can’t deny is that bank lending drove a bubble in Spanish house prices, which had been falling before the Euro, but rose dramatically under its influence, doubling between the start of the Euro and the crisis.

Figure 7

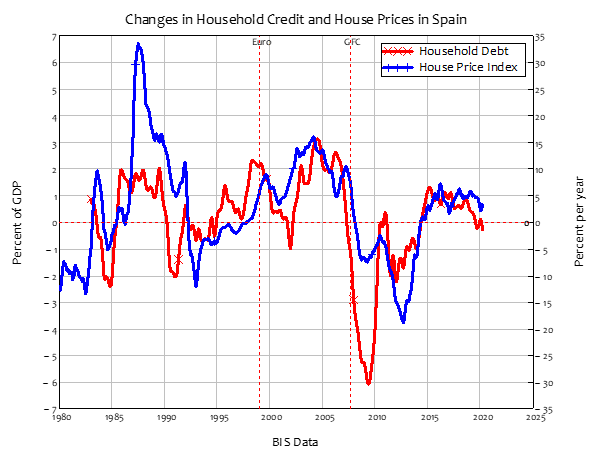

The link between household debt and house prices is not obvious: in Figure 7, the price index rises as the debt level rises from 1999 till the GFC, and falls as debt falls until 2014, but from then on, house prices are rising while debt is still falling. However, as I explain in this book, the real causal link is between change in household credit, and change in house prices. As Figure 8 indicates, this link holds across all of the data, from well before the Euro commenced until today.

Figure 8

Spain’s boom under the Euro prior to the GFC was caused by a private debt bubble, its crisis was caused by that bubble bursting, and the limits on government spending imposed by the rules of the Euro made its decline worse. The economy only recovered when its period of negative credit—which reduces aggregate demand—came to an end. But that period lasted almost a decade, and was far deeper than in the USA, where the maximum level of negative credit was 5.3% of GDP, versus 20% for Spain.

Private debt was still too high after the crisis, at 150% of GDP, versus roughly 80% of GDP for the 30 year. That alone was a problem without Covid-19. With it, the financial consequences of Covid-19 could be as great as its health consequences. The Covid-19 crisis has drastically exacerbated the impact of being highly levered. Laid-off workers are not able to pay their rent or mortgage without government support, landlords lose the cash flow to service their mortgages, corporations are forced into short-term debt where they have access to it to make up for diminished cash flow, and many corporations have gone and will go bankrupt, undermining the viability of the banks which lent to them. Government policies have reduced the impact to some extent, but the pressure of pre-Covid-19 financial commitments on a post-Covid-19 world are a major reason why there has been so much political opposition to the lockdown measures used to constrain the virus’s spread.

In this light, a proposal I make in the book is now needed much more. A “Modern Debt Jubilee” (see pages 117-119) would use the State’s limitless capacity to create money to reduce private debt significantly—by as much as 100% of GDP. But an essential aspect of that policy is that government has both a Treasury and a Central Bank that can together create its currency. Because of the Euro, Spain does not have that—nor does any other member of the Euro. I therefore believe that, unless there is a drastic change of not only heart but thinking at the ECB and the upper levels of European politics, the Euro in particular—and European economic policy in general—is a hindrance to managing the twin crises of private debt and Covid-19.

Deutsche Bundesbank. 2017. “The Role of Banks, Non- Banks and the Central Bank in the Money Creation Process.” Deutsche Bundesbank Monthly Report, April 2017, 13-33.

McLeay, Michael; Amar Radia and Ryland Thomas. 2014. “Money Creation in the Modern Economy.” Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin, 2014 Q1, 14-27.