I’m writing a book for Polity Press entitled The New Economics: A Manifesto. It has a long way to go, but this is the reasonably complete first chapter.

-

Why this Manifesto?

Even before the Covid-19 crisis began, the global economy was not in good shape, and nor was economic theory. The biggest economic crisis since the Great Depression began late in first decade of the 21st century. Called the “Global Financial Crisis” (GFC) in most of the world and the “Great Recession” in the USA, it saw unemployment explode from 4.6% of the US workforce in early 2007 to 10% in late 2009. Inflation turn into deflation— inflation of 5.6% in mid-2008 fell to minus 2% per year in mid-2009—and the stock market collapsed, with the S&P500 Index falling from 1500 in mid-2007 to under 750 in early 2009. The economy recovered very slowly after then, under the influence of an unprecedented range of government interventions, from the “cash for clunkers” scheme that encouraged consumers to dump old cars and buy new ones, to “Quantitative Easing”, where the Federal Reserve purchased a trillion-dollars-worth of bonds from the financial sector every year, in an attempt to stimulate the economy by making the wealthy wealthier.

This crisis surprised both the policy economists who advise governments on economic policy, and the academic who develop the theories and write the textbooks that train the vast majority of new economists. They had expected a continuation of the boom conditions that had preceded the crisis, and they in fact believed that crises could not occur. In his Presidential Address to the American Economic Association in January 2003, Nobel Prize winner Robert Lucas declared that crises like the Great Depression could never occur again because “Macroeconomics … has succeeded: Its central problem of depression prevention has been solved, for all practical purposes, and has in fact been solved for many decades. (Lucas 2003 , p. 1 ; emphasis added). Just two months before the crisis began, the Chief Economist of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the world’s premier economic policy body, declared that “the current economic situation is in many ways better than what we have experienced in years“, and predicted that “sustained growth in OECD economies would be underpinned by strong job creation and falling unemployment.” (Cotis 2007 , p. 7; emphases added)

How could they be so wrong? Economists could be excused for this failure to see the Great Recession coming if the crisis were something like Covid-19, when a new pathogen suddenly emerged out of China. That such a plague would occur was predicted as long ago as 1995 (Garrett 1995). But predicting when the pathogen would emerge, let alone what its characteristics would be, was clearly impossible. However, the epicentre of the Great Recession was the US financial system itself: the crisis came from inside the economy, rather than from outside. Surely there were warning signs? As Queen Elizabeth herself put it when she attended a briefing at the London School of Economics in 2008, “If these things were so large, how come everyone missed them?” (Greenhill 2008).

Not all economists did: there were some who warned that a crisis was not merely likely, but imminent. The Dutch economist Dirk Bezemer identified a dozen, of whom I was one (Keen 1995; Keen 2007; Bezemer 2009; Bezemer 2009; Bezemer 2010). Though these economists came from disparate backgrounds, Bezemer noted that they had one negative characteristic in common: “no one predicted the crisis on the basis of a neo-classical framework” (Bezemer 2010, p. 678).

“Neoclassical” economics is the method of thinking about and modelling the economy that the majority of economists use today—both Lucas and the OECD Chief Economist (then and now) are Neoclassical economists. For this reason, it is often also called “mainstream economics”. But it is not the only framework. Though the Neoclassical approach has dominated the discipline since the 1870s, it has never completely replaced previous approaches to economics, and rival approaches to it have developed since the 1870s.

These rival approaches in economics are very different to divisions of thought in sciences like physics. Albert Einstein’s General Relativity and Max Planck’s Quantum Mechanics have supplanted Isaac Newton’s physics in the realms of the very large (the Universe) and very small (the atom), but in between, Newton’s equations work very well. They are fundamentally different visions of the how the Universe operates, but anyone who rejects any of these approaches in physics in their relevant realm is highly likely to be a “crank”, who could never get a position in an academic physics department.

But in economics, different schools of thought have visions of how the economy works that are fundamentally in conflict. There is no way to partition the economy into sections where Neoclassical economics applies and others where Austrian, Marxian or Post Keynesian theory applies. On the same topic—say, for example, the role of private debt in causing financial crises—these schools of thought will have answers that flatly contradict each other.

Economists who do reject the mainstream, the so-called “heterodox” economists, also make up a significant minority of academic economists—as much as 1/6th of the discipline, going on a campaign by French academic economists in 2015 to establish a separate classification there (Lavoie 2015; Orléan 2015). So there is something fundamentally incompatible between the Neoclassical and heterodox approaches to economics, and the heterodox economists cannot be dismissed as cranks.

The common themes that Bezemer identified in the work of those who warned of the Global Financial Crisis indicate one of the key incompatibilities. Mainstream macroeconomic models ignore banks, debt, and money (Bezemer 2010, p. 678), while most heterodox economists regard banks, debt and money as crucial concepts in economics.

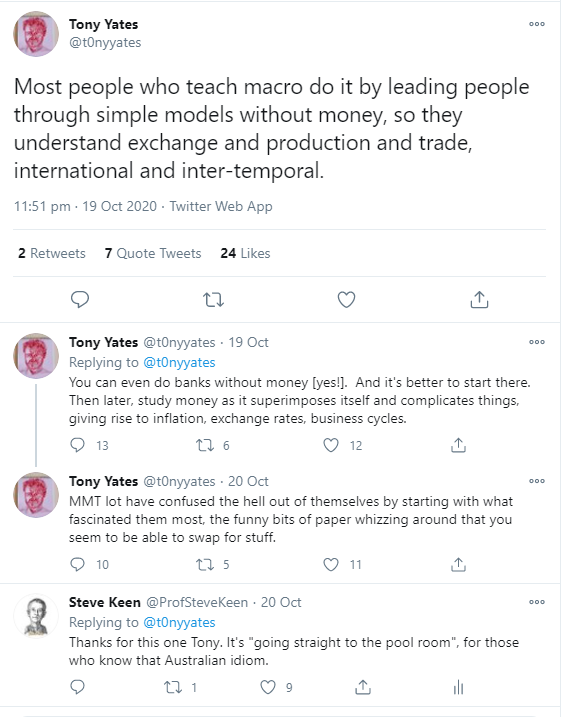

If you haven’t yet studied economics, or you’re in your early days of doing so at school or university, I hope this gives you pause: “Neoclassical economics doesn’t concern itself with money? But isn’t economics about money?” I, and many other heterodox economists, would respond “Yes, it is!”. But the mainstream long ago convinced itself that money doesn’t really affect the economy, and hence monetary phenomena are omitted from Neoclassical models. One Neoclassical economist put it this way on Twitter:

Most people who teach macro do it by leading people through simple models without money, so they understand exchange and production and trade, international and inter-temporal. You can even do banks without money [yes!]. And it’s better to start there. Then later, study money as it superimposes itself and complicates things, giving rise to inflation, exchange rates, business cycles.

Figure 1: Tony Yates defending moneyless macroeconomics on Twitter on October 19th 2020

This statement was made in late 2020—a dozen years after the failure of Neoclassical models to anticipate the crisis.

Why didn’t mainstream economists change their beliefs about the significance of money in economics after their failure in 2007? Here, paradoxically, economics has been like physics, in that significant change in physics does not, in general, occur because adherents of an old way of thinking become convinced by an experiment whose results contradicted their theory. Instead, these adherents continued to cling to their theory despite the experimental evidence it had failed. Humans, it appears, are more wedded to their beliefs about reality—their “paradigms”, to use Thomas Kuhn’s famous phrase (Kuhn 1970)—than reality itself. Science changed, not because these scientists changed their minds, but because they were replaced by new scientists who accepted the new way of thinking. As Max Planck put it:

“a new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.” (Planck 1949, pp. 33-34)

Here, economics is different, largely because economic truths are different to scientific ones in that they are historical, whereas scientific truths are unchanging. The key scientific experiment that led to Einstein’s theory of relativity was the Michelson-Morley experiment in 1887, which attempted to measure the speed of the Earth relative to “the aether”, the medium that scientists then thought allowed light to travel through space. Michelson and Morley’s experiments found that there was no discernible relative motion—which implied that the aether did not exist. This experiment can be repeated at any time—and has been repeated, with increasingly more sophisticated methods—and the result is always the same. There is no way of getting away from it and returning to a pre-Relativity science—nor is there any desire to do so by post-Relativity physicists.

In economics, it is possible to get away from failures of theory to play out as expected in reality. An event like the GFC occurs only once in history, and it cannot be reproduced to allow old and new theories to be tested against it. As time goes on, the event itself fades from memory. History can help sustain a memory, but economic history is taught at very few universities. Economics don’t learn from history because they’re not taught it in the first place.

Economics is also a moving target, whereas physics, relatively, is a stationary one. When a clash between theoretical prediction and empirical results occurs in physics, the state of unease persists until a theoretical resolution is found. But in economics, though a crisis like the GFC can cause great soul searching at the time, the economy changes over time, and the focus of attention shifts.

Finally, unlike physicists, economists do want to return to pre-crisis economic theory. Events like the GFC upset the totem that characterises Neoclassical economics, the “supply and demand” diagram, in which the intersecting lines determining both equilibrium price and equilibrium quantity, and in which any outside intervention necessarily makes things worse by moving the market away from this equilibrium point. This image of a self-regulating market system that always returns to equilibrium after an “exogenous shock” is a powerful emotional anchor for mainstream economists.

These factors interact to make economics extremely resistant to fundamental change. In physics, anomalies like the clash between the results of the Michelson-Morley experiment and the predictions of pre-Relativity physics persist until the theory changes, because the experimental result is eternal. The anomaly doesn’t go away, but the theory that it contradicted dies with the pre-anomaly scientists, who can’t recruit followers amongst new students, because they are aware of the anomaly, and won’t accept any theory that doesn’t resolve it.

In economics, anomalies are forgotten, and new students can be recruited to preserve and extend the old beliefs to cover new phenomena. School and university economics courses become ways of reinforcing the Neoclassical paradigm, rather than fonts from which new theories spring in response to failures of the dominant paradigm.

This means that intellectual crises in physics are intense but, to some extent, short-lived. The crisis persists until a new theoretical breakthrough resolves it—regardless of whether that breakthrough persuades existing physicists (which as a rule, it doesn’t). The “anomaly”, the empirical fact that fundamentally contradicts the existing paradigm, is like the grain of sand in an oyster that ultimately gives birth to a pearl: the irritation cannot be avoided, so it must be dealt with. It is the issue that believers in the existing paradigm know they cannot resolve—though it may take time for that realisation to sink in, as various extensions of the existing paradigm are developed, each of which proves to be partially effective but inherently flawed. It is the thing young scientists are most aware of, the issue they want to be the one to resolve. As their lecturers who stick to the old paradigm age, the students take in the old ideas, but are actively looking for where they are wrong, how these contradictions might be resolved.

Once a solution is found, the protestations of the necessarily older, aged and often retired champions of the previous paradigm, mean nothing. Ultimately, all the significant positions in a university department are filled by scientists who are committed to the new paradigm.

As that is pushed further, then, as philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn (Kuhn 1970) explains, the new paradigm undergoes a period of rapid extension just like its predecessor, but ultimately this new paradigm will confronts its own critical anomaly, and the science falls into crisis once more.

This is a punctuated path of development. It starts with the development of an initial paradigm by a great thinker, around whom a community of followers develop. They extend the core insights and thus form a science, and initially enjoy a glorious period of the dance between observation and theory, where observations confirm and extend the paradigm. But finally, some prediction the theory makes is contradicted by observation. After a period of denial and dismay, the science settles into an unhappy peace: the paradigm is taught, but with less enthusiasm, the anomaly is noted, and the various withing-paradigm attempts to resolve it are discussed. Then, out of somewhere, whether from a Professor (Planck) or a patents clerk (Einstein), a resolution comes. Rinse and repeat.

Those punctuations never occur in economics, and because the punctuations don’t occur, neither does the kind of revolutionary change in the discipline that Kuhn vividly describes for physics and astronomy.

An economic crisis, when it strikes, does disturb the mainstream. Their textbook advice—if the crisis is empirical rather than theoretical—is thrown out the window by policymakers while the crisis lasts. But mainstream economists react defensively. They justify the extraordinary measures by the unexpected nature of the crisis, then treat the contradiction the crisis poses for their theory as an aberration, which can be handled by admitting some modifications to the core theory. One example is the concept of “bounded rationality” promoted by Joe Stiglitz (Stiglitz 2011; Stiglitz 2018). This can be invoked to say that, if everyone were strictly rational, then no problem would arise, but because of “bounded rationality”, the general principle doesn’t apply and, in this instance, a deviation from the theoretical canon is warranted.

Minor modifications are made to the core Neoclassical paradigm, but fundamental aspects of it remain sacrosanct.

Over time, the crisis passes—whether that was aided or hindered by the advice of economists. A handful of economists break with the majority, which is how heterodox economists are born. But the majority of students become as entranced as their teachers were by the fundamentally utopian vision of Neoclassical economics—a world without power, in which everyone receives their just rewards, and in which regulation and punishment are unnecessary, because The Market does it all. These new students replace their masters, and they continue to propagate the Neoclassical paradigm.

That fraction which breaks away—the roughly one in six academic economists who refuse to ignore the crisis, reject the mainstream, and then get attracted to a competing paradigm (like Post Keynesian, Marxian or Austrian Economics)—live on in universities, but don’t get the positions, promotions or research funds that accrue to the true believers in Neoclassical economics. Instead, they get positions in lowly ranked universities which leading Neoclassicals aren’t interested in—like the University of Western Sydney, and Kingston University London, where I was respectively a Professor and Head of School, or in Departments of Business or Management. The influence of heterodox economists is limited, but they exist at all times.

Given this failure to break the dominant Neoclassical paradigm despite numerous crises, both empirical and logical (Keen 2011), the discipline sits in a state of perpetual and understated crisis: a minority of heterodox economists vocally reject the Neoclassical mainstream, but the Neoclassical paradigm remains dominant. It evolves over time, but it is never replaced in the way that obsolete paradigms are replaced in science.

If you’re thinking “But what about the Keynesian revolution?”, that was snuffed out by John Hicks, with a paper that purported to reach a reconciliation between “Mr Keynes and the Classics” (Hicks 1937) by developing what became known as the IS-LM model. Though this model was presented and accepted by the majority of economists as “a convenient synopsis of Keynesian theory”, Hicks later admitted that it was a Neoclassical, “general equilibrium” model he had sketched out “before I wrote even the first of my papers on Keynes” (Hicks 1981, p. 140).

The gap between what this model alleged was Keynesian economics, and the actual economics of Keynes, was enormous, as can readily be seen by comparing Hicks’s “suggested interpretation” of Keynes, and Keynes’s own 24-page summary of his economics in “The General Theory of Employment” (Keynes 1937), which was published 2 months before Hicks’s paper. The key passage in Keynes’s summary is the following:

The theory can be summed up by saying that … the level of output and employment as a whole depends on the amount of investment… More comprehensively, aggregate output depends on … But of these several factors it is those which determine the rate of investment which are most unreliable, since it is they which are influenced by our views of the future about which we know so little.

This that I offer is, therefore, a theory of why output and employment are so liable to fluctuation. (Keynes 1937, p. 221. Emphasis added)

Keynes model sees the level of investment as depending primarily upon investors’ expectations of the future, which are uncertain and “unreliable”. Hicks completely ignored expectations—let alone uncertainty—and instead, modelled investment as depending upon the money supply and the rate of interest:

This brings us to what, from many points of view, is the most important thing in Mr. Keynes’ book. It is not only possible to show that a given supply of money determines a certain relation between Income and interest…; it is also possible to say something about the shape of the curve. It will probably tend to be nearly horizontal on the left, and nearly vertical on the right…

Therefore, … the special form of Mr. Keynes’ theory becomes valid. A rise in the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital only increases employment, and does not raise the rate of interest at all. We are completely out of touch with the classical world. (Hicks 1937, p. 154)

The schism between Hicks’s Neoclassical purported model of Keynes and Keynes’s own views was so great that it gave rise to one of the key heterodox schools of thought, “Post Keynesian Economics”. So “the Keynesian revolution” didn’t happen, though Post Keynesians themselves—including myself (Keen 2020)—have developed approaches to economics that are revolutionary. But a revolution in thought, like that from Ptolemy’s earth-centric vision of the solar system to Copernicus’s sun-centric vision, has not happened.

The above paints a bleak picture of the prospects of replacing Neoclassical economics with a fundamentally different and far more realistic paradigm. But there have been changes over time that make this more feasible now than it was at Keynes’s time.

Foremost here is the development of the computer, and computer software that can easily handle large scale dynamic and even evolutionary processes. These developments have occurred outside economics, and especially in engineering, physics and meteorology. There are limitations of the applicability of these techniques to economics, largely because of the fact that economics involves human behaviour rather than the interaction of unconscious objects, but as I will argue in the following chapters, these limitations distort reality far less than the Neoclassical fantasy that economic processes occur in or near equilibrium.

The development of the Post Keynesian school of thought after the Great Depression is also important. There were strident critics of the Neoclassical mainstream before the Great Depression, such as Thorstein Veblen (Veblen 1898; Veblen 1908; Veblen 1909), but no truly revolutionary school of economic thought. The development of this heterodox school over the 8 decades between the Great Depression and the GFC meant that, when that crisis struck, there were coherent explanations of it—indeed, prescient warnings of it (Keen 1995; Godley and Wray 2000; Godley 2001; Godley and Izurieta 2002; Keen 2006; Keen 2007)—that did not exist when Keynes attempted his revolution.

Social media has also allowed student movements critical of Neoclassical economics to evolve, flourish and persist in a way that was impossible before the Internet. I led the first student revolt against Neoclassical economics at Sydney University in 1973 (Butler, Jones et al. 2009), but that was restricted to just one university in far-away Australia. French students established the “Protest Against Austistic Economics” in 2000, which had somewhat more traction, but whose main legacy was an online journal called the Real World Economic Review. The real breakthrough came with a protest by economics students at the University of Manchester in the UK in 2012, in response to the failure of their teachers to take the GFC seriously in their macroeconomics courses. As they put it, “The economics we were learning seemed separate from the economic reality that the world was facing, and devoid from the crisis that had made many of us interested in economics to begin with”. Their Post Crash Economics movement in turn spawned the international Rethinking Economics campaign, which now has groups in about 100 universities across the world.

There are therefore students eager for approaches to economics that break away from the Neoclassical mainstream, methods of analysis which can easily supplant the dated equilibrium methods used by Neoclassical economics, and rival schools of thought with an intellectual tradition spanning 70 years on which an alternative paradigm can be constructed. What we lack is a university system in which these conditions can foment change as occurs in physics.

Hence this Manifesto: I want to reach potential students of economics before they embark on a university course of study that will attempt to inculcate belief in the Neoclassical paradigm, and that will drive away those that can’t accept it.

-

Appendix

-

References

Bezemer, D. J. (2009). “‘No one saw this coming’ – or did they?” VOX EU, from https://voxeu.org/article/no-one-saw-coming-or-did-they.

Bezemer, D. J. (2009). “No One Saw This Coming”: Understanding Financial Crisis Through Accounting Models. Groningen, The Netherlands, Faculty of Economics University of Groningen.

Bezemer, D. J. (2010). “Understanding financial crisis through accounting models.” Accounting, Organizations and Society

35(7): 676-688.Butler, G., E. Jones, et al. (2009). Political Economy Now!: The struggle for alternative economics at the University of Sydney. Sydney, Darlington Press.

Cotis, J.-P. (2007). Editorial: Achieving Further Rebalancing. OECD Economic Outlook. OECD. Paris, OECD. 2007/1: 7-10.

Garrett, L. (1995). The coming plague : newly emerging diseases in a world out of balance / Laurie Garrett. New York, New York : Penguin Books USA Inc.

Godley, W. (2001). “The Developing Recession in the United States.” Banca Nazionale del Lavoro Quarterly Review

54(219): 417-425.Godley, W. and A. Izurieta (2002). “The Case for a Severe Recession.” Challenge

45(2): 27-51.Godley, W. and L. R. Wray (2000). “Is Goldilocks Doomed?” Journal of Economic Issues

34(1): 201-206.Greenhill, S. (2008). ‘It’s awful – Why did nobody see it coming?’: The Queen gives her verdict on global credit crunch. Mail Online. London.

Hicks, J. (1981). “IS-LM: An Explanation.” Journal of Post Keynesian Economics

3(2): 139-154.Hicks, J. R. (1937). “Mr. Keynes and the “Classics”; A Suggested Interpretation.” Econometrica

5(2): 147-159.Keen, S. (1995). “Finance and Economic Breakdown: Modeling Minsky’s ‘Financial Instability Hypothesis.’.” Journal of Post Keynesian Economics

17(4): 607-635.Keen, S. (2006). Steve Keen’s Monthly Debt Report November 2006 “The Recession We Can’t Avoid?”. Steve Keen’s Debtwatch. Sydney. 1: 21.

Keen, S. (2007). Deeper in Debt: Australia’s addiction to borrowed money. Occasional Papers. Sydney, Centre for Policy Development.

Keen, S. (2011). Debunking economics: The naked emperor dethroned? London, Zed Books.

Keen, S. (2020). “Emergent Macroeconomics: Deriving Minsky’s Financial Instability Hypothesis Directly from Macroeconomic Definitions.” Review of Political Economy

32(3): 342-370.Keynes, J. M. (1937). “The General Theory of Employment.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics

51(2): 209-223.Kuhn, T. (1970). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Lavoie, M. (2015). “Should heterodox economics be taught in economics departments, or is there any room for backwater economics?” INET Economics https://www.ineteconomics.org/uploads/papers/Lavoie.pdf.

Lucas, R. E., Jr. (2003). “Macroeconomic Priorities.” American Economic Review

93(1): 1-14.Orléan, A. (2015). Economists also need competition. Le monde. Paris.

Planck, M. (1949). Scientific Autobiography and Other Papers. London, Philosophical Library; Williams & Norgate.

Stiglitz, J. E. (2011). “Rethinking Macroeconomics: What Failed, and How to Repair It.” Journal of the European Economic Association

9(4): 591-645.Stiglitz, J. E. (2018). “Where modern macroeconomics went wrong.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy

34(1-2): 70-106.Veblen, T. (1898). “Why is Economics not an Evolutionary Science?” THE QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

12(4): 373-397.Veblen, T. (1908). “Professor Clark’s Economics.” THE QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

22(2): 147-195.Veblen, T. (1909). “The Limitations of Marginal Utility.” The Journal of Political Economy

17(9): 620-636.