I made the macabre joke at the end of my post on losing David Graeber, that “Now we know why we speak of 20:20 vision, and 20:20 hindsight. We thought it was an ophthalmologist’s crazy numbering system. In fact, it was a warning from a time traveler.” That year is about to pass, and we’ll soon look back on 2020 in hindsight—as we once did on 1920, when the Spanish Flu ended.

Will we be any the wiser? I unfortunately expect that the wish to see this year in the rear vision mirror will translate into a wish to “return to normal”, where normal is defined as “what was happening before 2020”. However, that pre-2020 normal itself was based on so many unsustainable trends—most significantly of all, the unsustainable trend of human exploitation of the biosphere. 2020 will probably be looked back upon as the year in which the unsustainability of those trends was first made apparent by Covid-19. But we humans are likely not to learn that lesson, given our desire to escape the pain this year has caused.

Some Twitter correspondents have wondered whether The Roaring Twenties were a similar response, after the privations forced upon America by the Spanish Flu. I think there’s wisdom in that thought, and I do expect we’ll attempt likewise. But we will be bereft of the low levels of private debt, and low relative levels of the stock market, that made that euphoria possible in 1920.

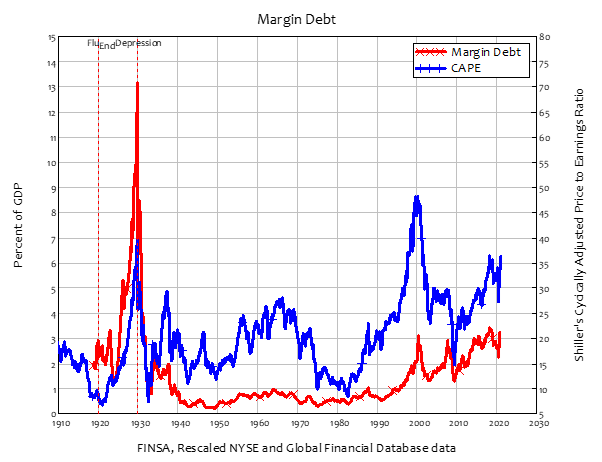

This will mainly be a personal reflection on 2020, but I can’t not post the following chart, showing the level of margin debt and the stock market valuation over the last century. When the Spanish Flu ended, the stock market was at almost its lowest level in history (it hit that level just six months later) and margin debt was comparable to today’s levels, which are six times the post-WWII median of about 0.5% of GDP, but exploded during the 1920s to 13% of GDP (after adjusting pre-WWII data slightly to match post-WWII records).

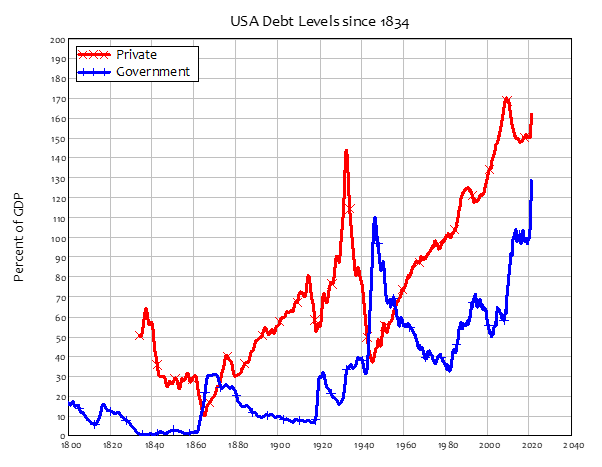

Especially when combined with the historically high levels of private debt, I simply can’t see the 2020s being anything like the 1920s.

Instead, I think it will be the decade where our foolishness in trusting economists on climate change comes back to bite the economy big-time.

For me, 2020 has been a year of enormous change, all driven by Covid-19. I began the year in Amsterdam, where I had bought a flat with my partner Nisa. I’ve ended it in Bangkok, where we fled in March to escape the Netherlands, which has been as much of a shit-show on Covid-19 as the UK or Sweden—and we formalized our relationship by getting married yesterday.

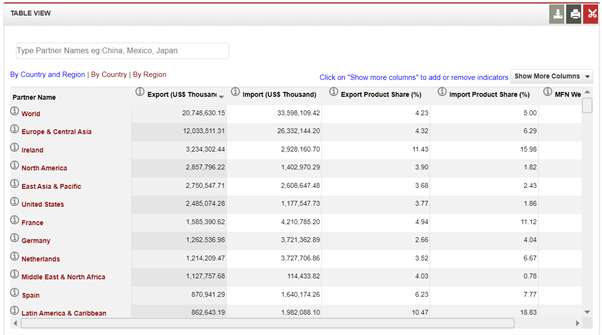

We’ll now look to buy a place here, for both personal and climate-change related reasons. One reason I bought in Amsterdam was that, on some metrics, it was better placed than any other country in Europe to cope well with climate change. The Dutch are the best in the world at managing water, both in terms of keeping it out with dykes, and in managing it in agriculture; and as by far the world’s leading exporter of food in per capita output terms, they were likely to cope better with the climate-change-driven breakdown of agriculture.

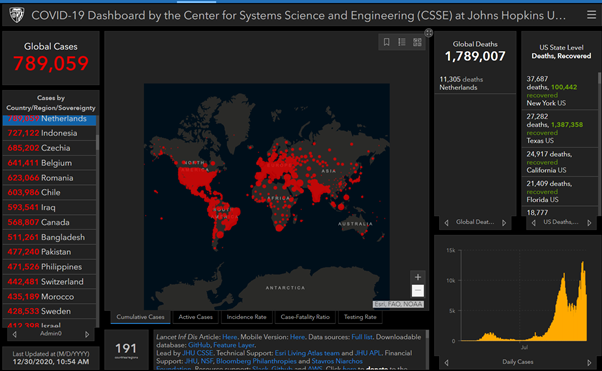

Then they made a complete fist of Covid-19, I expect by falling for the same “herd immunity” nonsense as did Sweden, though not as explicitly. This country of 17 million has as bad a record on Covid-19 as the UK.

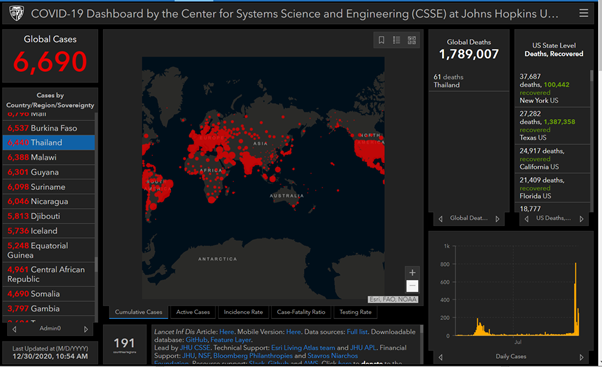

I was lucky to have the option of moving to Thailand, given Nisa’s nationality: though she has lived in The Netherlands for over 25 years, she is still a Thai citizen, and moving here was straightforward for her. I made the move initially thinking that it would slow down how quickly I would get the virus, thus giving more time for a vaccine to be developed. Until the recent huge outbreak in a Burmese-migrant-worker enclave on the outskirts of Bangkok, it looked like I had instead drawn the Ace of Hearts from the pack, by choosing somewhere that had eliminated the virus completely.

Even with the recent outbreak—which also illustrates the weakness, in our “spaceship Earth” world, of treating any subgroup as something we can just exploit without consequences—I think Thailand will succeed in eradicating its second wave, as The Netherlands blunders into its third.

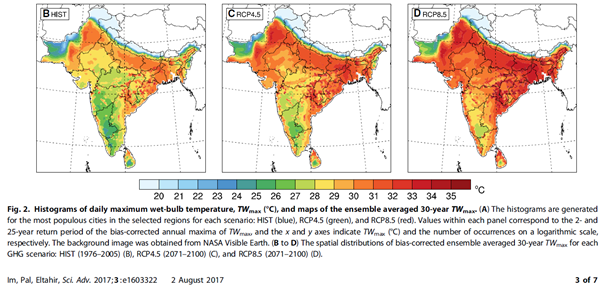

There are family reasons for having a home here as well—we live in the same suburb as Nisa’s eldest son, and several sisters—but for me it’s also another climate change hedge. Though Thailand is likely to suffer from higher heat thanks to global warming, it isn’t projected to suffer from the “35°C wet bulb” crisis that will hit the Indian subcontinent.

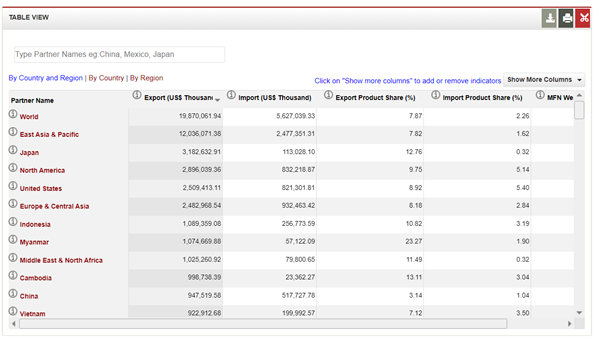

It is also a net food exporter, and the food supply chain is a lot shorter, even in Bangkok, than for any Western city—including Amsterdam. So that implies relative safety, if food supplies are challenged—and prices rise dramatically as a result.

Places like the UK, which imports about 30% of its food, are likely to be severely challenged when food exporters are hit by climate change breakdowns of major weather systems.

My main reason for wanting hedges against climate change, apart from the merely selfish motivation, is that it seems I’m the person who is best placed to expose the fraud that has underpinned the sanguine forecasts of the economic impact of climate change made by Neoclassical economists like Nordhaus. I want to pursue that all the way from academic articles like “The appallingly bad neoclassical economics of climate change” to being an expert witness if, as I hope, they are eventually prosecuted under the developing laws against ecocide.

Looking forward(?) to 2021, I’ll be developing more research to support that critique of Nordhaus and friends, as well as working on monetary policies to address climate change. I have been invited to write a review paper on economic analysis of climate change Proceedings of the Royal Society A, which I’ll start as soon as I finish the first draft of The New Economics: A Manifesto for Polity Press.

I had hoped to finish that book before the end of the year—that is, in less than two days’ time! I’m close, but I won’t make it. However, I think I’ll have it done by the end of the first week of January, and I’ll post that first draft here (for patrons only).

Next cab off the rank—probably simultaneously with Royal Society paper—will be a policy paper on carbon rationing. Having read the drivel on carbon pricing by economists like Nordhaus, I’m convinced that carbon pricing is far too little, far too late, and rationing of carbon (with tradeable Universal Carbon Credits) is the only feasible monetary means to slow down climate change.

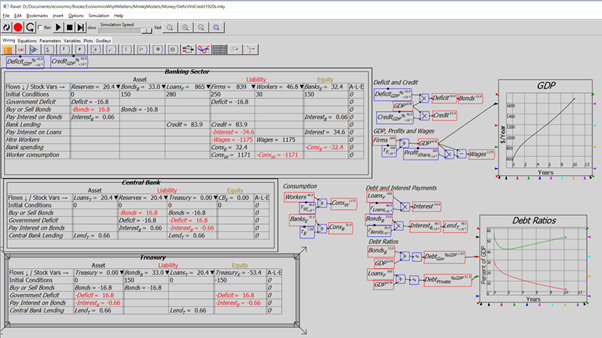

I’m also about to apply for another grant from Friends Provident Foundation to continue the development of Minsky. It has come a long way already thanks to their £200,000 grant, and we have a great development team now, with Russell Standish still the chief programmer, but ably supported by Wynand Dednam, whom we’ve been able to employ fulltime thanks to the grant.

There’s a lot more to do though: we have only just started adding new tabs as part of the interface, the plots need a lot of work, we want to be able to import models from other system dynamics programs (to encourage more use of Minsky, which is one of the very few Open Source system dynamics programs). With the grant, we’ve taken Minsky from a program that didn’t support basic editing operations like copy, cut and paste to an up-to-date GUI. Now we need to round out its system dynamics features and make it a first-class presentation tool.

There’s a ton more work in the pipeline—far too much work, and I’m always playing catch-up with my commitments. One day I hope to have a fully-funded research team working with me, but for now I’m very grateful to my Patrons for the support you give me that enables me to do this work full-time. I just wish there wasn’t so much of it!

Keep safe everyone. Vaccines have started to roll out, but there are many months to go before they will enable us to put Covid-19 in the same category as smallpox or polio. You’ll need as much of your good health as you can hang on to to cope with what I think the 2020s have in store for us.