One year ago today, on March 18th 2020, my wife Nisa and I took off from Amsterdam’s Schipol Airport, bound for Bangkok.

The motivation wasn’t tourism, but escape from what was clearly turning into a disaster in Europe in general, and the UK and The Netherlands in particular. I had worked in London since 2014, and bought a flat in Amsterdam in 2018. Covid was out of control in both places, and I wanted to minimize my chances of catching it. With my income coming from my supporters on Patreon (at https://www.patreon.com/profstevekeen), I had the rare privilege of being able to move anywhere on the planet, without jeopardizing my income. From my research into Covid-19 trends, Thailand was the place to be.

Back then, I still thought that I was merely delaying the inevitable: I expected that I would eventually catch Covid, and find out the hard way whether my 67-year-old immune system was up to the challenge. A year later, it’s obvious that moving to Thailand was the one of the best decisions I’ve ever made: so long as I remain here, I am highly unlikely to catch Covid-19, since Thailand is one of the few countries to have effectively eliminated it.

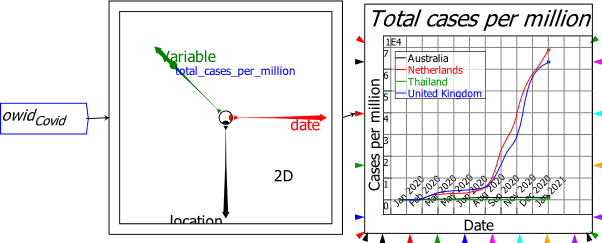

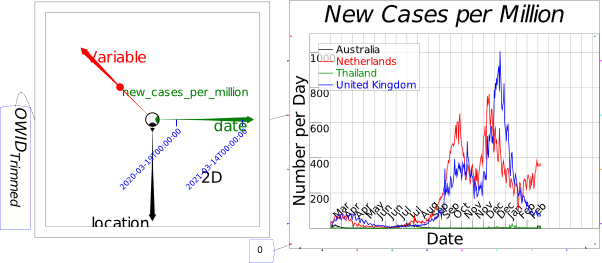

The UK and The Netherlands, on the other hand, have been Covid basket cases. Total verified cases in both countries now exceed 6% of the population (60,000 per million inhabitants)—see Figure 1.

Figure 1: The Our World in Data Covid database in Ravel©™, focusing on the UK, Netherlands, Thailand & Australia

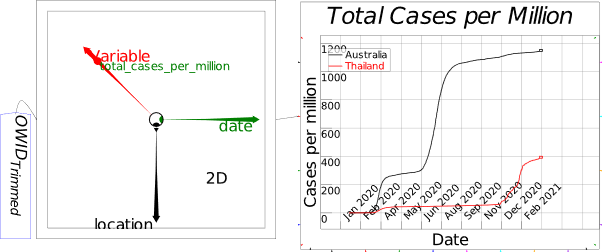

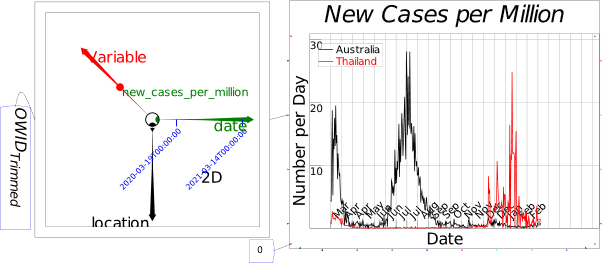

Cases are so much lower in Thailand (and my home country of Australia) that they’re best shown on a separate graph: see Figure 2. In percentage terms, 0.04% of Thailand’s population have had Covid; Australia’s figure is just over 0.1%.

Figure 2:Covid total cases per million inhabitants in Australia and Thailand

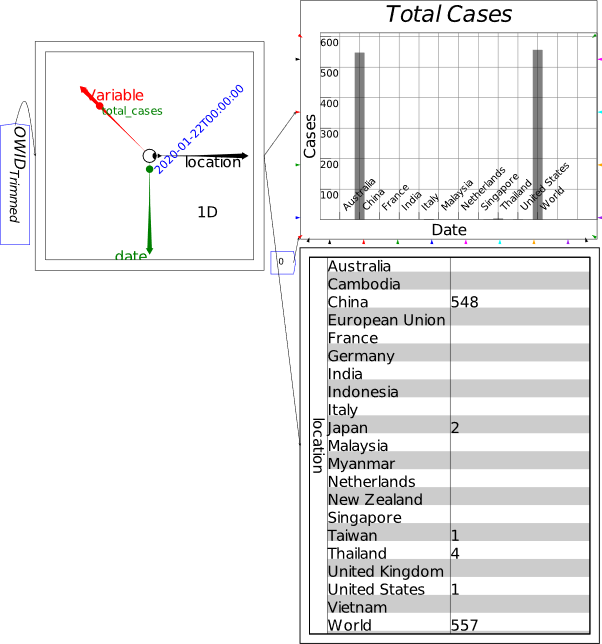

This long-term success is despite Thailand being the second country, after China, to record a Covid case. The Our World In Data Covid database starts on January 22nd, 2020. Figure 3 shows that back then, Asia was the hotspot—and therefore, the part of the world to avoid. But the trend over time told a different story: numbers in the rest of the world rose much faster than in Asia.

Figure 3: Total cases as of January 22nd 2020

There was one puzzle for me too. I was keeping a close eye on the 4 countries where I could choose to live during the pandemic—Australia (my country of birth); the UK (where I worked and had a resident visa until 2022); The Netherlands (where Nisa lived); and Thailand (Nisa’s country of birth, though she hadn’t lived there for 25 years). All the way through February, as cases rose virtually everywhere, there were NO cases in The Netherlands. This didn’t make sense to me: Amsterdam is the biggest tourist city in Europe: surely someone had come in from Wuhan with the virus?

Then on February 27th, Holland’s Covid “drought” broke: 1 case turned up. There were 6 cases two days later on the 29th, 18 another two days later March 2nd. Cases trebling every two days was not a good look.

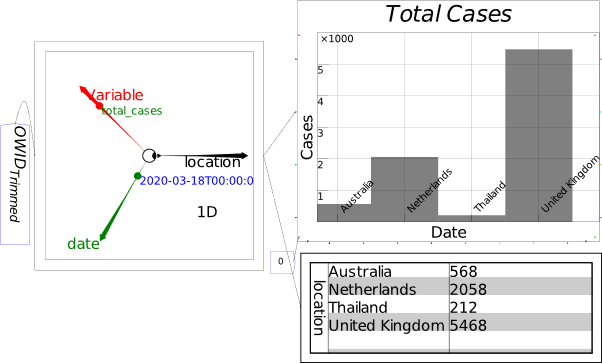

I was in Sydney at the time, working with Drs Russell Standish and Wynand Dednam on Minsky—and also Ravel ©™, the program I’m using to create the figures in this post (see the end of this post for more about Ravel). When I left Sydney on March 11, there were 503 cases in The Netherlands, and just 59 in Thailand. By the 18th, when we departed for Thailand, The Netherlands had 2058 cases to Thailand’s 212 (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Case levels in the countries where I could have lived during the pandemic on my day of departure from Europe

We arrived with barely a day to spare: on March 20, Thailand started closing its borders to foreigners. We were also amongst the last to get in without a compulsory 14 day quarantine—though we had to sign up to a contact-tracing App before we could get through customs.

I could have made a mistake of course: Thailand’s early results could have been a fluke, and we could have been stuck in a 3rd world country where only one of us was a citizen. Only it wasn’t a fluke, as later events showed—see Figure 5, which illustrates the multiple waves that have overwhelmed the UK and The Netherlands. This “3rd World” country continued to do much, much better than its “1st World” rivals.

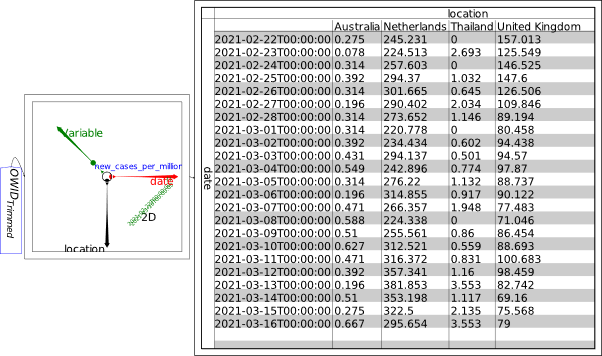

Figure 5: New cases per million from our arrival in Thailand on March 19 2020

Thailand is currently experiencing a second wave, which I am confident it will manage to suppress. Where is it, you ask? You have to drop the scale of the plot from hundreds to tens to see it—and Australia’s successfully suppressed second and third waves as well. Thailand’s second wave peaked at under 30 new cases per million, versus the thousand cases per million in the UK—see Figure 6.

Figure 6: Australia and Thailand’s well-managed second and third waves

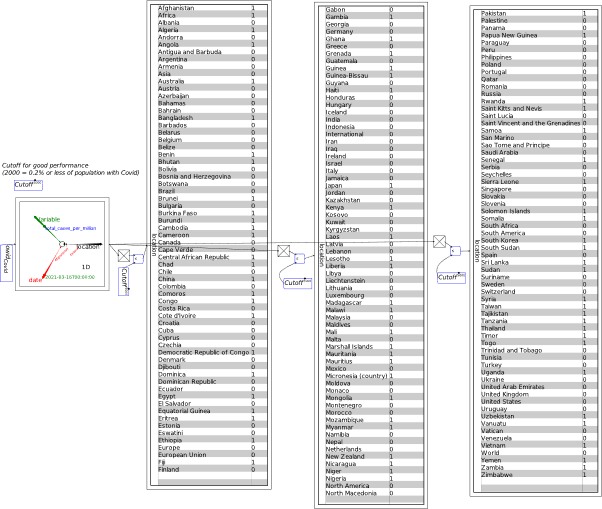

Why has Thailand—along with Australia, New Zealand, Taiwan, China, Mongolia, Vietnam, and Cambodia and quite a few others—been a success story, while the rest of the world, especially Europe, the USA and South America, have been failures (see Figure 7)?

Figure 7: Covid success & failure: countries with 0.2% or less of population with Covid shown as 1, others as 0

I’ve seen so many one-factor arguments—or rather, excuses—made by people residing in one of the basket-case countries. With obvious exceptions from the data shown in brackets, the key fallacious arguments are that:

- It’s the heat (New Zealand, Mongolia);

- It’s being an island (China, Thailand, Vietnam, Mongolia—with the UK itself an obvious counter example);

- It’s the low population density (Taiwan, Thailand, China, Vietnam);

- It’s the public’s previous experience with SARS (Australia, New Zealand);

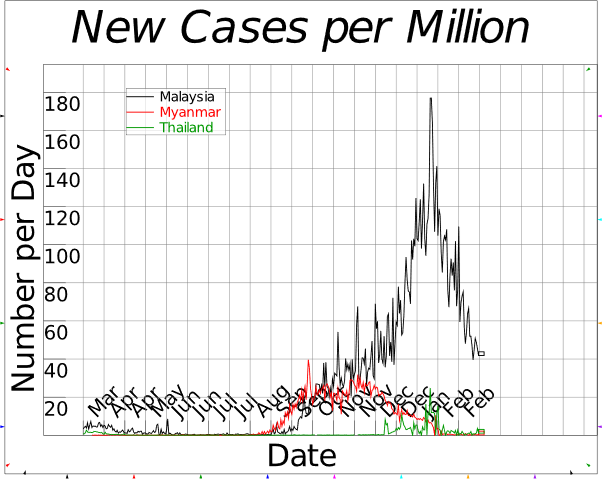

- Asians have natural immunity (New Zealand, Australia—with Malaysia and Burma as counter examples: both border Thailand, are ethnically similar, and yet are relative failures);

- It’s obesity and co-morbidities in the West, making old people more susceptible there (Australia and New Zealand have high obesity & co-morbidity rates too); and

- Only authoritarian governments have suppressed it (New Zealand, Australia, Taiwan, Thailand—with Burma as an example of an authoritarian failure, until recently);

Figure 8: If it’s all about race, why then is Malaysia (and Burma) a relative failure, compared to Thailand?

From my perspective of living in one of the success stories, and with friends and family in another (Australia), it comes down not to any mono-causal explanation, but to good multifaceted public policy, followed well by the public. This involved a multitude of interventions:

- strictly enforced lockdowns;

- strict quarantine for international arrivals, so that cases can’t be imported from overseas;

- isolation of regions, so that an outbreak in one can’t spread to another;

- effective contact tracing, so that any outbreak was limited to immediate contacts, who themselves were put into total lockdowns while being tested daily for symptoms;

- universal mask wearing, so that on two occasions, a quarantine breach in Thailand led to zero new cases;

- widespread availability of masks (surgical masks were distributed by the government in Thailand for the princely sum of 10 cents each—which still allowed the Thai manufacturers a 20% profit);

- compulsory mask-wearing on public transport and in all large enclosed public venues (shopping centres, etc.);

- bans on small venues like restaurants and bars, with financial compensation for owners and staff; and reduced utility costs; and

- government financial support to workers and businesses, which allowed poor people to survive despite their jobs disappearing because of lockdown.

Yes, there have been stuff-ups—Australia’s several quarantine breaches, Thailand’s outbreaks in migrant worker enclaves—but well designed, enforced and followed public policies have worked every time to bring the outbreaks back under control. These countries have done what pandemic specialist Yaneer Bar-Yam said would work—and he was right, it has worked.

When I look at what has happened in the UK in particular, I can only manage a macabre laugh. I see good friends like John Hearn whine about the impact of lockdowns on the economy (and challenge the veracity of the data as well), when what happened in the UK is better described as not a lockdown, but a “mockdown“. Reactive politicians delaying action until the outbreak forced it? Check. Tourists flying in without facing mandatory quarantine? Check. An inability to manufacture masks and other Personal Protective Equipment? Check. Mask-wearing not enforced on public transport, or virtually anywhere? Check. Huge social events allowed? Check. Restaurants opened to stimulate the economy? Check. Contact tracing that was more a handout to rich friends than a program? Check. Restrictions lifted well before zero cases were achieved, let alone sustained? Check. No wonder the UK’s numerous “lockdowns” haven’t worked. It’s had the worst of both worlds.

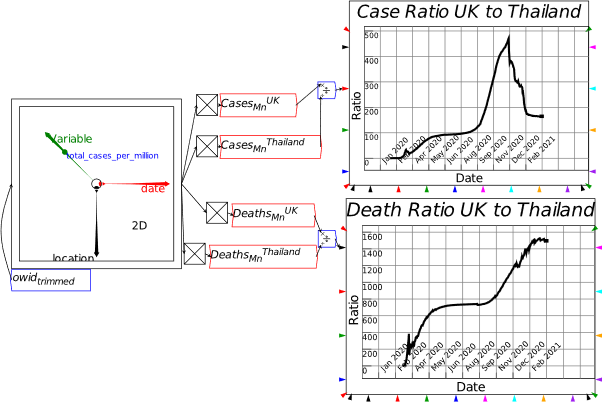

In sum, the UK’s outcome, compared to Thailand’s, is a record of staggering British incompetence. These two countries have very similar populations (66 2/3rd million versus 69 2/3rd million), and similar exposures to the rest of the world through tourism and trade. One has the advantage of a sea border (bar Northern Island), a much higher per capita GDP (the UK’s is 7 times Thailand’s), and a long and proud history of national health. Yet the UK’s total case count peaked at almost 500 times Thailand’s, while its death rate hit 1500 times—see Figure 9.

Figure 9: UK’s total cases and deaths per million compared to Thailand

Things aren’t all rosy in Thailand, but mainly because tourism was 20% of its GDP, and the failure of much of the rest of the world to contain Covid has trashed this core part of its economy. Sporadic outbreaks in the various Covid success stories have also stopped the revival of tourism between them. Clearly, some policy will need to be introduced to enable tourism to open up despite these flare-ups, without requiring residents of these countries to go into lengthy quarantine on arrival: as with Thailand itself, an outbreak with a maximum of 1750 cases in one day, and well under 5 cases per million per day, is a totally different ballgame to the UK, which is still experiencing almost 100 cases per million per day (see Figure 10), even with the benefit of its first Covid success story, the rapid rollout of vaccines.

Figure 10: Thailand’s recent outbreak is still well below the UK and Netherlands levels

The odds that a tourist to Thailand from China or Australia will have the virus is extremely low, even if new cases aren’t zero. Perhaps there could be a brief quarantine in a luxury resort, contact tracing, plus acceptance of basic restrictions (masks in public places), for people from almost-zero-Covid countries? With China alone responsible for about half of Thailand’s pre-Covid tourism, this could halve the damage to Thai incomes from Covid.

Emotionally, my decision to move to Thailand has made tracking Covid in the rest of the world feel like watching a slow-motion train-wreck: it’s awful, but you can’t avert your eyes. Other people who made a similar move to safe countries from dangerous ones—such as my friend and Patreon supporter Craig Tindale, who moved back to Australia from the USA, or my ex-PhD student Tim Gooding, who moved from the UK to Taiwan—feel likewise. We’re emotionally affected, because we worry about friends who weren’t able to uproot and move like we were, but we’re detached at the same time, because we know that what we’re witnessing in Europe and the USA can’t happen to us.

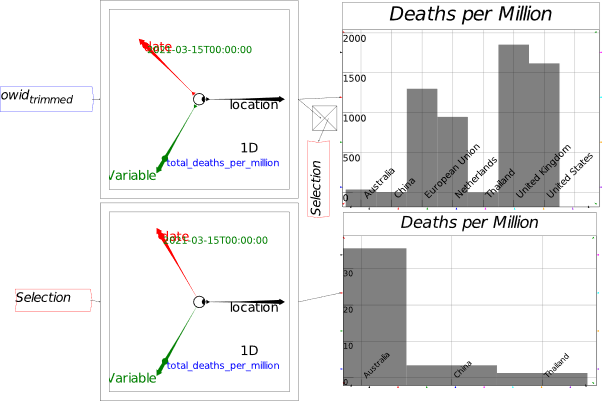

Two things that I have found truly remarkable over the past year is how little countries that have failed have learnt from those that have succeeded, and how little the leaders of these countries have been punished by their electorates. To me, it beggars belief that Boris Johnson would easily win an election right now, when his bumbling has given the UK the worst death toll in the world—see Figure 11, as well as Figure 9. My only explanation for this is that most people simply aren’t doing what I’m doing: looking at the comparative data.

Figure 11: US and UK Death rates are several orders of magnitude greater than Thailand’s

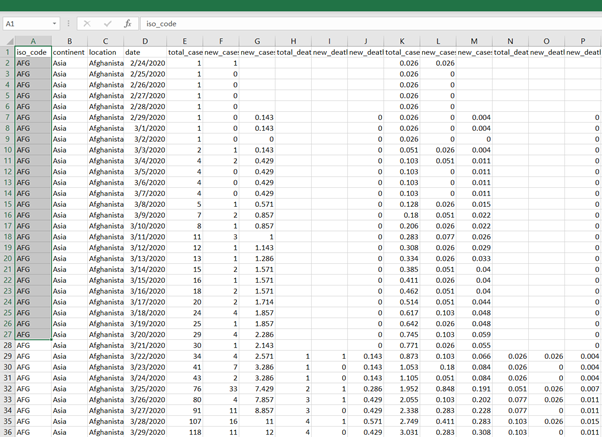

Partly that’s because data on Covid, though readily accessible, is hard for people who aren’t data professionals to analyze: they are forced instead to rely on standard selections made by news media, or on readily accessible webpages. Comprehensive data, like the Our World in Data database I’m using in this post, looks like Figure 12 when loaded into Excel. That’s enough to stop most users in their tracks.

Figure 12: The Our World in Data Covid-19 database, loaded into Excel

Ravel©™

The inaccessibility of data like that shown in Figure 12 in standard programs like Excel inspired me to develop Ravel, the program I’ve used to display the data in the previous figures. Ravel is a visual interface to complicated, multi-dimensional data, and it is far easier to manipulate than the Pivot Tables which Excel uses for data like this. I’ve been working on it for a long time with Russell Standish, and we’ve finally developed an “alpha” version that we’re willing to put into the hands of novice users. It’s still some way from a full commercial version, but it is stable enough now for it to be used by people who are put off by Excel’s Pivot Tables. Experienced Pivot Table users will, I expect, also find Ravel far easier to use, though it is still rough at the edges (for one thing, our bar charts suck).

At the end of the month—specifically on my birthday on March 28th, because, well, why not?—I’ll give a free copy of Ravel to my Patreon supporters. It’s a generic data analysis tool which can handle any data you have in CSV format (at present: more formats will come later). What I’ve shown here is just the tip of the iceberg of Ravel‘s capabilities: I’ll post some more blog entries in the next few days to demonstrate what else Ravel can do.

If you’d like to take Ravel for a test drive yourself, then sign up to either my Patreon page https://www.patreon.com/ProfSteveKeen, or to Minsky’s at https://www.patreon.com/hpcoder/, for as little as $1 a month, and download a copy on March 28th.