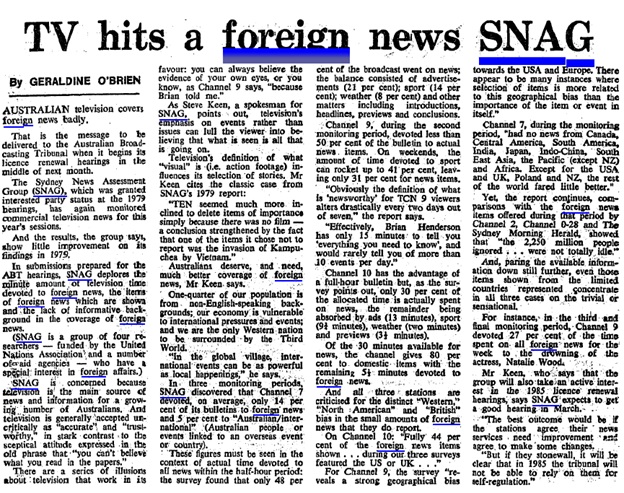

Yesterday, Greg Jericho of The Guardian posted this tweet about the movie Don’t Look Up, and I lost the plot:

Figure 1: https://twitter.com/GrogsGamut/status/1475997904342896641?s=20

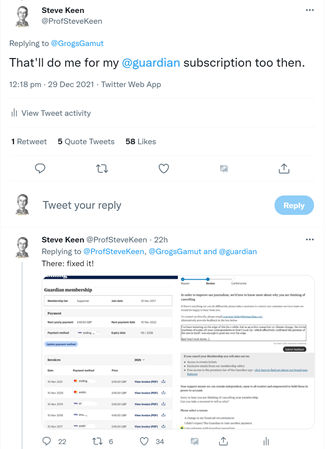

You don’t need to subscribe to read The Guardian—unlike many major newspapers—but I have been doing so since 2017. I’d been thinking about ending it for some time, and this was the trigger:

Figure 2: https://twitter.com/ProfSteveKeen/status/1475999567690682368?s=20

Greg took this as a juvenile reaction—which, without any background, was a reasonable interpretation:

Figure 3: https://twitter.com/GrogsGamut/status/1476156247573286916?s=20

In fact, this was just the catalyst to throw in the towel on something I’ve been trying to do for about forty years: to improve how the media handles complex issues like climate change—though when I started, in 1978, the focus was on how it tackled news from developing countries.

I threw in the towel on that activity—which I’ll detail below—a long time ago. But I still continued trying to support journalism directly. I subscribed to three newspapers—The Guardian, The Sydney Morning Herald, and The New York Times, and also a news aggregation service called Inkl.

After Greg’s tweet—but not only because of it, by any means—I decided to throw in the towel on my personal financial support for old-fashioned journalism as well. I’ll extricate myself from the SMH and the NYT at some point—as a correspondent pointed out, The Guardian deserves credit for making it dead easy to unsubscribe—and I’ll just use Inkl when I want to read a newspaper article, as opposed to a tweet or blog.

I’ve been thinking of doing this quietly for a year or more now. What led to me doing it noisily was the incredibly polarized way that different audiences have reacted to Don’t Look Up.

The public, it appears, has embraced it: it’s the most highly watched movie of 2021—and if you haven’t yet watched it, I do recommend adding to its numbers.

Climate scientists and activists, many of whom I know personally—though only a handful face-to-face, thanks to Covid—have been strongly moved by it, and that applies to me too.

Journalists and movie critics, on the other hand, have—like Greg—tended to pan it. This included The Guardian’s movie critic in a review entitled “Look away: why star-studded comet satire Don’t Look Up is a disaster“. I was willing to ignore movie critics on this, but there were also many similar reactions from other journalists. Why the divide?

I think it’s because the movie triggered the two very different perspectives that journalists on the one hand, and climate scientists and other experts on the other, have of today’s media process. The astronomer Neil deGrasse Tyson summed up the feelings of my side of this divide very nicely:

Figure 4: https://twitter.com/neiltyson/status/1476293956153581578?s=20

Tyson was right: anyone who has been on the scientist’s side of today’s media circuit felt the message of the movie deeply, and were moved by it. But many people who sit on the other side of that circuit—the media side—felt caricatured by the movie, and were insulted by it.

This is not to personally disparage any of the journalists I’ve dealt with in the many media interviews, daytime talk shows, morning and evening business programs, blah blah blah, that I have undertaken over the last two decades. There’s quite literally not one person I’ve interacted with in the media who was anything like the profoundly shallow hosts of the TV show that DiCaprio, as “Professor Mindy”, interacted with. It’s “the system”, rather than the individuals, that generates the shallowness. But Blanchett and Perry had to personally embody that systemic shallowness, to effectively convey what it feels like for climate scientists, to raise the alarm and not be heard, within the confines of a 2 ½ hour movie.

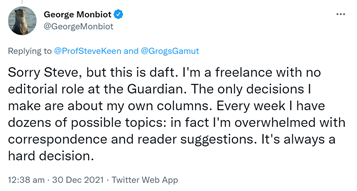

I did have one gripe, which also involves The Guardian, and which was the reason I pulled the trigger on my views on this issue with them rather than, say, the Sydney Morning Herald or the New York Times. That was that I had discussed my paper exposing the real shallowness of the economic analysis of climate change with George Monbiot, sent the paper to him pre-press, and then heard nothing back—until he responded to my dummy spit yesterday:

Figure 5: https://twitter.com/GeorgeMonbiot/status/1476185955287633924?s=20

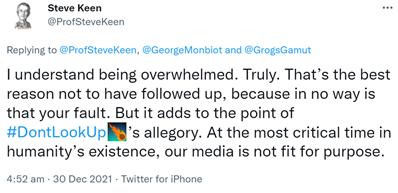

As I wrote back, this is absolutely fine. George had the time to correspond with me beforehand, but was overwhelmed with other correspondence, and didn’t get the time to look at the paper after I sent it to him. I know the feeling—to a lesser degree—with the 1-5 requests I get a week from young academics to comment on their research. I just can’t: if I did, I’d never get my own work done.

Figure 6: https://twitter.com/ProfSteveKeen/status/1476249676558991361?s=20

This raises the issue of why the media is not fit for purpose.

Some of this relates to the failure of the mainstream print and broadcast media to respond to the challenge of the Internet. The obvious thing to do was to establish a micro-payments system, so that, if you read an article, you paid a very small fee to the media outlet providing it. But there were and still are enormous technical difficulties with making that possible, and even today—almost 40 years after the birth of the internet—a viable micropayments system for media consumption doesn’t exist. It should be possible to pay a tiny amount—a cent or so—for every article you read, with the individual cents developing into a substantial revenue flow for the media company and its journalists. But it still isn’t: Inkl is about the best I’ve seen out there, and I’ll continue to support it, but it hasn’t developed the following amongst either media consumers or producers to make the media itself a viable business once again.

The end result of this has been a drastic fall in the funding of mainstream media from news alone—or rather, from selling advertisements alone. This is probably the nub of the problem that mainstream media had in adapting to the Internet. Its business model was to sell you, the media watcher, to the advertisers. You never were the media’s consumer: you were instead, its product: they sold eyeballs to advertisers. The Internet required a 180° flip to see the media watcher as the consumer, and to sell content to you, rather than to sell you to the advertisers (this is an argument that I first heard put, very entertainingly, by the Australian historian and commentator Humphrey McQueen).

Since it never managed to make the flip, media companies adopted various mixtures of three losing strategies:

- Paywall your content so only subscribers can see it, just as only buyers of physical newspapers in the past could read them;

- Make it free, but continue selling eyeballs to advertisers; and

- Make it free and encourage a body of loyal supporters as well.

Since none of these schemes has come anywhere near approaching the “rivers of gold” that used to flow from having a monopoly of classified advertisements in the pre-Internet days, today’s newspapers are a shadow of their former selves. Some star journalists make a decent living still—I hope George Monbiot is one, and Larry Elliott another, to mention my two favorite journalists at The Guardian. But they have to do their research with far less support than they could have counted on in the pre-Internet days. Hence George has to scan his own mail, and misses a paper showing that economists have made up their own numbers on climate change.

That’s not to say that everything was perfect in the media in the pre-Internet days, however. One obvious weakness—to me—of media coverage then was the focus on “events” rather than “issues”. The media would report that “the peasants are revolting” (or starving); they wouldn’t report on “why the peasants are revolting”.

From my perspective as the newly hired Education Officer for the Australian Freedom from Hunger Campaign (AFFHC) in late 1977, this was one reason why the Australian public had such a dim view of developing countries, even though Australia was the anomaly of a predominantly white, developed nation, in close proximity to a predominantly brown, under-developed region of the world.

I developed several campaigns to address this, in concert with my colleagues at the AFFHC, and activists in various other overseas aid charities including Community Aid Abroad (CAA), Australian Catholic Relief (ACF), and the Australian Council of Churches (ACC). These included a very successful letter-writing campaign, a submission to the Australian Broadcasting Tribunal—which showed that Channel Ten, then owned by Rupert Murdoch, did not report the invasion of Cambodia by Vietnam until ten days after it started, when the capital Phnom Penh fell—and (of most relevance to my dummy spit yesterday), a series of seminars on coverage of Third World news in the Australian media, which I established with the assistance of Ranald MacDonald (no, not Ronald), then the Managing Director of Melbourne’s paper of record, The Age.

Ranald was committed to what he called “Issues Oriented Journalism”, and he and his right-hand person Sally White teamed up with me to run the first seminar for journalists on a key issue at the time, the unexpected collapse of India’s fledgling Janata (“People’s”) Party in 1977, and the return to power of the authoritarian figure of Indira Gandhi.

Figure 7: 1st page of the Janata Party comparative press coverage seminar

The seminar was a great experience (with one hiccup, which I won’t elaborate upon here), and I gave a talk on it to a conference at Griffith University in 1979. The audience included Jocelyn Chey, then Director of the Australia-China Council, and she approached me to run a similar seminar between Australian and Chinese journalists in Beijing in the winter of 1981/82. To prepare for it, I produced a dossier covering every article in the leading Australian newspapers on China in the period from July of 1980 till June of 1981—which, as the Australian Journalists’ Association noted, ran to over 3,000 pages.

Figure 9: The Australian Journalists’ Association note on the dossier on Australian coverage of China that I assembled for SAPS in 1980/81

The seminar was a great success.

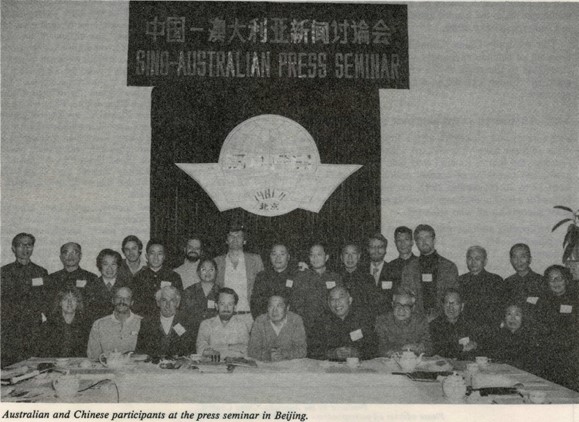

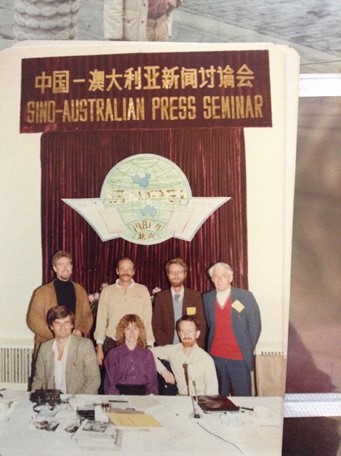

Figure 10: The Australian and Chinese delegates to SAPS in Beijing, 1981/82

But a subsequent one on Southeast Asia, held in Australia, was not—probably because there wasn’t the same appeal to journalists of a sponsored trip to China during the very early days of China’s abandonment of socialism (the trial of the Gang of Four occurred while the seminar was being held).

I am sure that if I had established this venture in the USA at the time, then the much larger media there would have enabled a viable market, and I could have turned improving the media into a successful business—which the Internet would have then ruined. But that wasn’t possible in Australia, so I went on to other activities before I finally decided to go back to university and do a PhD in Economics, to challenge Neoliberalism at the source.

That career change didn’t extinguish my interest in, and to a degree, love for the media though.

I used my media knowledge to raise awareness of the approaching Global Financial Crisis between 2006 and 2008—and then saw Kevin Rudd respond to my warnings by restarting the Australian housing bubble.

That is also one of the messages of Don’t Look Up. The fictional scientists in the movie, like actual climate scientists in real life, also felt that by alerting politicians (starting with The President, no less), and then by alerting the Press, that the People in Charge would Do Something!

Which they did: they developed a scheme to mine the comet for minerals (while—spoiler alert—also building an escape rocket just-in-case). Watching the movie just played back the message that experience has given me that everything about our society—our media, our political system, our economy—is dysfunctional in the face of a systemic crisis.

I had this realization before seeing Don’t Look Up, which is why I decided to accept Victor Kline’s invitation to become the primary Senate candidate for The New Liberals at the next Australian election. If getting the ear of politicians (via the media) hasn’t worked, why not see what I can do if I get the mouth of one instead?

But trying to change the trajectory we’re on, simply by informing the media that economists don’t know what they’re talking about, and the threats from climate change are far, far greater than a few percent fall in GDP some time in the distant future? Someone tell me I’m dreaming.

So, was my dummy spit over Greg Jericho’s tweet immature? For a 68-year-old, probably yes. But after 50 years of seeing the deterioration of the media, from both its own internal weaknesses and its ineffective response to the rise of the Internet, it was an immature way to admit to myself that my hope for a substantial media is probably forlorn.

The twitter storm over Don’t Look Back was as good a time as any to end my subscription to old-time media outlets.