As a close friend and colleague of Michael Hudson (Hudson 2004, 2018), I was aware of much of the content of David’s Debt: the First 5000 Years (Graeber 2011) before I read it. But David weaved the tale of debt into the recorded history of humanity in a way that made it revelatory, even to cognoscenti like Michael and me.

He communicated the true tale of how money did not spring out of barter, but evolved out of debt, better than anyone before him. His quirky, bemused writing style took that tale to a huge popular audience, bigger than any in economics since the heyday of J.K. Galbraith—and David was arguably the wittiest public intellectual since JK.

My personal debt to David is for his exposition of the evolution and role of credit throughout history. As a non-mainstream economist, I have always rejected the economic textbook myth of barter. But though I failed to succumb to the standard pedagogical brainwashing that rinses thoughts of money from the minds of mainstream economists, I lacked the knowledge of where and when this pivotal human social construct originated.

David provided that knowledge, and showed how the chains of private debt which enslave us today emanated out of the glue that binds us together as social animals.

The famous intuition by Robin Dunbar, that humans lived in groups of about 150, indicated that this was about the maximum number of interpersonal relations that one human mind could track. Pre-sedentary-civilisation societies were bonded by the human desire to be well regarded. This created many networks, including those of interpersonal debt: who had done a favour to you, to whom did you owe a favour?

Once agriculture allowed the development of much larger communities, the role of keeping track of debts was institutionalised. Originally this was within the priesthood of the society’s religion, which made the religious community a focal point in commercial as well as ideological life. In our time, the banks have taken on that role—and abused it more than most priesthoods would contemplate doing.

David’s vision enabled me to see our modern financial institutions as a continuity, and a perversion, of that quintessential human trait, of keeping track of our debts. What we have now is an institution that wishes to create more such debts, for its own profit. Whereas religions extolled the virtue of not being in debt—”neither a borrower nor a lender be“—supported Jubilees (Hudson 2018), and railed against the practice of usury, banks encourage the creation of debt, champion the creditor over the debtor, and have pushed interest-based financing into every corner of our lives.

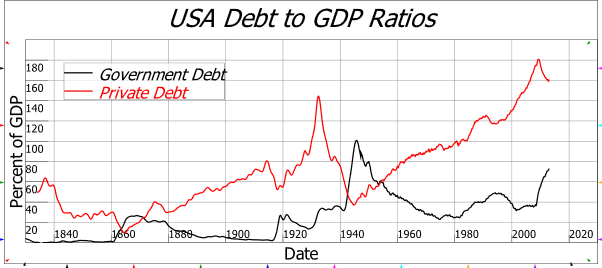

This aspect of modern society is what gave David’s historical detective work such contemporary significance. Those of us who understand the role of private debt in capitalism—and David was one of that tiny band—know that it is the explosion of private debt, and not of government debt, that has caused almost all of capitalism’s periodic financial crises (Vague 2019). And yet in contrast with reality, mainstream economics ignores private debt, with its fiction that banks are “mere intermediaries” who take in the deposits of savers and lend them out to borrowers, and rails against government debt.

The former is a fallacy, the latter is a farce. Banks are not intermediaries between savers and borrowers, but are instead the originators of both debt and debt-based money. The government does not borrow from the public when its spending exceeds taxation revenue, but in fact creates money for the public which, unlike credit money, does not come with a debt obligation for the public itself.

But because this fallacy and this farce are believed by much of the public, and most politicians and journalists, skyrocketing levels of private debt have gone unnoticed, while their demonising of government debt has led to far too little fiat-based money being created—which further drives the public into private debt.

Figure 1: Private debt has almost always been higher than government debt, and its booms and busts are the root causes of economic turmoil, to which government debt rises in response

I thought I would always have David’s voice to join with mine, Michael Hudson’s, and the small band of monetary realists, in fighting against this fallacy and this farce. His sudden death in 2020 was, for me personally, the most shocking event in that systemically shocking year. We’ll soldier on regardless, but we’ll soldier less well without him, and with far less panache and wit than we would have done, had he continued to be one of our number.

Graeber, David. 2011. Debt: The First 5,000 Years (Melville House: New York).

Hudson, Michael. 2004. ‘The Archaeology of Money: Debt versus Barter Theories of Money’s Origins.’ in L. Randall Wray (ed.), Credit and state theories of money: The contributions of A. Mitchell Innes (Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, U.K).

———. 2018. …and forgive them their debts: Lending, Foreclosure and Redemption From Bronze Age Finance to the Jubilee Year (Islet: New York).

Vague, Richard. 2019. A Brief History of Doom: Two Hundred Years of Financial Crises (University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia).