“I fancy that over-confidence seldom does any great harm except when, as, and if, it beguiles its victims into debt.” (Fisher 1933, p. 341)

The man who penned those words wrote them from bitter experience. Irving Fisher, who is far better known for the statement that “Stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau“, was the Paul Krugman of his day: the world’s most famous Neoclassical economist.

Fortunately, unlike Krugman, Fisher recovered from this mental illness.

Unfortunately, he didn’t do so until after his belief in the Neoclassical theory of finance—which he developed (Fisher 1930)—effectively sent him bankrupt in The Great Crash of 1929.

Believing that stock prices accurately reflected future earnings, and that leverage plays no role in determining asset prices, Fisher used margin debt to parlay a personal worth of about US$10 million into a US$100 million share portfolio—and then was reduced to penury when the stock market crashed.

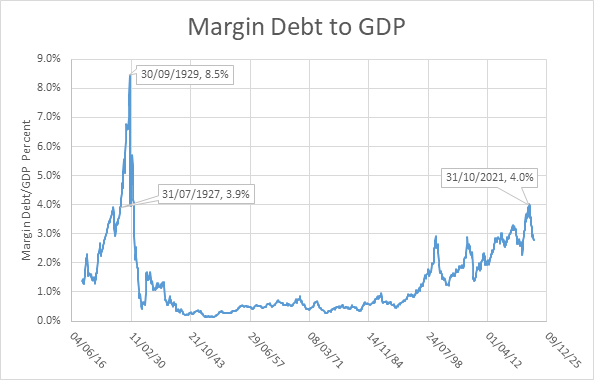

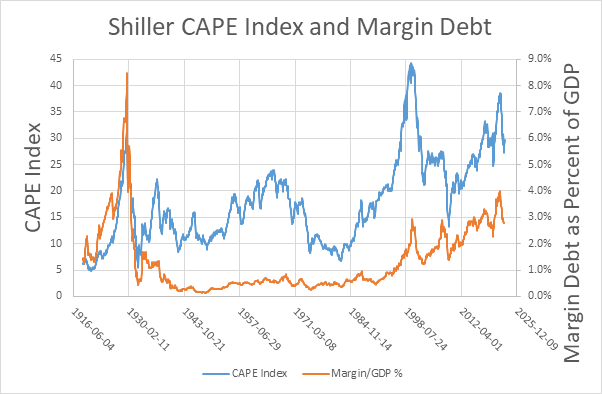

I raise this historical anecdote today because margin debt is now at levels that were previously only seen during the height of the Roaring Twenties, from mid-1927 until it all came crashing down with The Great Crash on October 29, 1929—see Figure 1.

Figure 1: Margin debt as a percentage of GDP

The allure of margin debt is that it amplifies your gains: in the 1920s, levered speculators salivated at the prospect of doubling their money every time the stock market rose by just 10%.

The pitfall they ignored was that, when the stock market crashed, the peculiar feature of a margin loan—the “margin call”, which requires the speculator to add more money to return the value of the portfolio to its initial level—kicked in. When the market fell 10% on one day in 1929, most speculators couldn’t make the margin—even after liquidating everything.

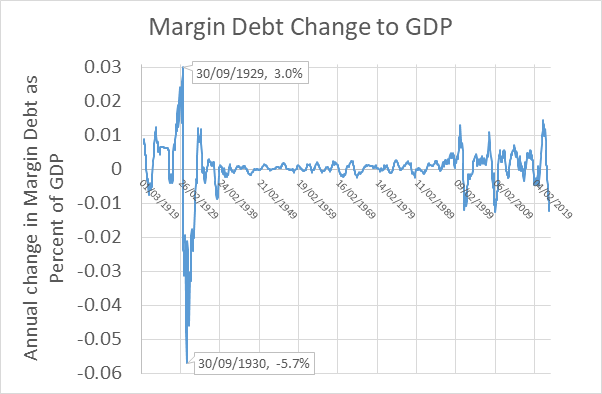

When you look at the sheer scale of margin debt in the 1920s, it’s no wonder that the Great Depression ensued afterwards. Right before the crash, the growth in margin debt peaked at 3% of GDP. By the 3rd quarter of 1930, it was almost minus 6% of GDP—see Figure 2.

Figure 2: Change in margin debt as a percentage of GDP

Fisher the mainstream economist was bewildered by these developments at first. But Fisher the rebel economist finally worked out why this mattered: money borrowed from a bank (even if indirectly via a broker) adds to the supply of money, and to demand for goods and services as well as shares, while debt repaid reduces the money supply and demand just as much. Therefore, the repayment or writing off of debt caused a decline in aggregate demand:

A man-to-man debt may be paid without affecting the volume of outstanding currency j for whatever currency is paid by one, whether it be legal tender or deposit currency transferred by check, is received by the other, and is still outstanding. But when a debt to a commercial bank is paid by check out of a deposit balance that amount of deposit currency simply disappears.(Fisher 1932, p. 15)

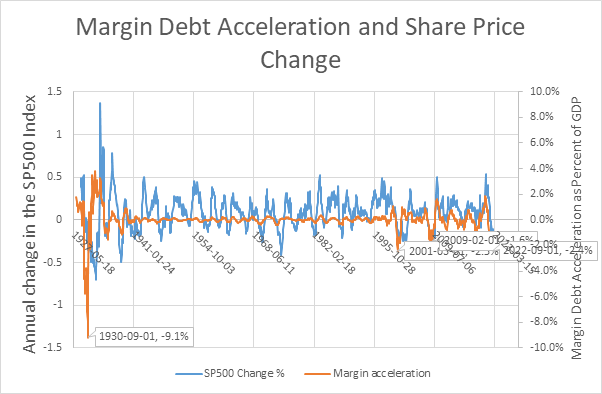

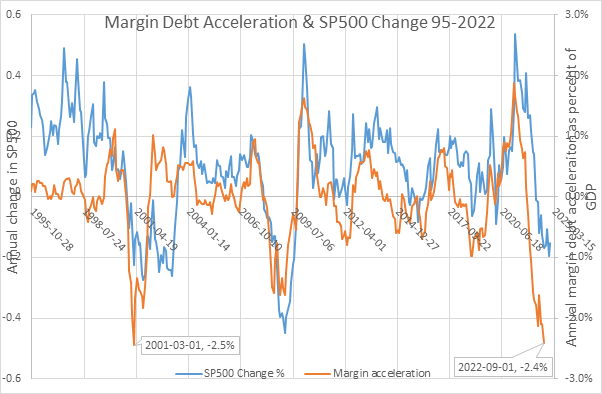

This phenomenon hits asset markets particularly hard, because debt is used to buy assets far more than it is used to buy goods and services. New debt—in this case, new margin debt—is a substantial source of the demand for shares, so that the acceleration of margin debt drives change in share prices—see Figure 3.

Figure 3: Margin Debt Acceleration to Share Price Change 1920s-2020s

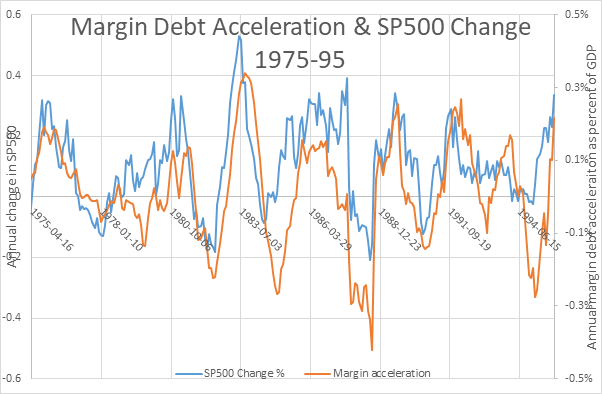

The tsunami-scale of the collapse of both margin debt and share prices in The Great Crash makes it hard to see how relevant this force still is today, so here are 2 extracts from that chart, Figure 4 for 1975 till 1995 (the era before and after the Greenspan Put) and Figure 5 for 1995 till today (the era before and after Bernanke’s Quantitative Easing).

Figure 4: The relationship from 1975-95

Figure 5: The relationship from 1995 till today

There’s one caveat in comparing margin debt today to back in Fisher’s day: in part thanks to Fisher’s campaign against margin debt during the 1930s, a “margin loan” today allows the borrower to no more than double the value of shares she can buy: a speculator with $100,000 to bet on stock prices can buy $200,000 with a margin loan. In Fisher’s day, the factor was tenfold: $100,000 in cash could be used to buy a $1 million portfolio, with the other $900,000 supplied by the broker.

Given that lesser leverage, the pressure of decelerating margin debt isn’t as severe as in Fisher’s day. But the message that these chart scream is that the current stock market downturn still has a long way to go.

Happy New Year everyone…

Fisher, Irving. 1930. The Theory of Interest: as determined by impatience to spend income and opportunity to invest it (Porcupine Press: Philadelphia).

———. 1932. Booms and Depressions: Some First Principles (Adelphi: New York).

———. 1933. ‘The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions’, Econometrica, 1: 337-57.