For those that are too young to remember, the legendary English comedy show Monty Python had a famous sketch about a disgruntled customer of a pet shop, who realised he had been sold a dead Parrot. The shopkeeper steadfastly refused to admit that the Parrot was dead:

CUSTOMER: I wish to complain about this parrot what I purchased not half an hour ago from this very boutique.

SHOPKEEPER: Oh yes, the, uh, the Norwegian Blue … What’s, uh … What’s wrong with it?

CUSTOMER: I’ll tell you what’s wrong with it, my lad. ‘E’s dead, that’s what’s wrong with it!

SHOPKEEPER: No, no, ‘e’s uh, … he’s resting.

CUSTOMER: Look, my lad, I know a dead parrot when I see one, and I’m looking at one right now.

SHOPKEEPER: No no, he’s not dead, he’s, he’s restin’! …

Why has this sketch come to mind for me? Because Gregory Mankiw, the author of one of the world’s most popular economics textbooks, has just shown that this fictional shopkeeper has nothing on Mankiw and his mainstream economics colleagues, when it comes to pretending that something which is dead is actually alive and well.

The Dead Parrot in question is the “Money Multiplier”: the theory that banks create money by lending out reserves. It’s also called “Fractional Reserve Banking”.

The 6th edition of Mankiw’s Macroeconomics textbook (there’s now a 9th edition, but I’m not about to waste money buying a dead parrot) explains the Money Multiplier by starting with “an imaginary economy” in which the money supply is initially $100 in cash. Then the population deposits all that cash in “First National Bank”. The money supply now consists of $100 in bank deposits, while all the cash is in the vault of First National Bank. Next First National Bank decides to make loans, so it lends out $90 in cash. The money supply now consists of $100 in demand deposits and $90 in cash. Mankiw declares that:

The depositors still have demand deposits totaling $100, but now the borrowers hold $90 in currency. The money supply (which equals currency plus demand deposits) equals $190. Thus, when banks hold only a fraction of deposits in reserve, banks create money. (Mankiw 2012, p. 333)

The process then repeats, with the loan recipients depositing their $90 in cash in another bank, which also hangs on to 10% of the cash ($9) and lends out the rest ($81), also in cash. Mankiw explains that:

The process goes on and on. Each time that money is deposited and a bank loan is made, more money is created… The amount of money the banking system generates with each dollar of reserves is called the money multiplier…

The money multiplier is the reciprocal of the reserve ratio. If R is the reserve ratio for all banks in the economy, then each dollar of reserves generates 1/R dollars of money. In our example, R = 1/10, so the money multiplier is 10. (Mankiw 2012, p. 334)

There are numerous problems with this as a model of bank money creation, not the least of which is that it only works if all loans are in cash (a point that Mankiw at least notes). Though that may have happened in the 19th century Wild West, today, banks make loans by increasing a customer’s deposit account, and recording precisely the same sum as a debt of the customer to the bank. No cash is involved, nor are bank reserves “lent out”.

Non-mainstream economists like me and my contemporaries and predecessors have been trying to kill this false theory for decades—see these references for a sample of the anti-Money-Multiplier literature (Moore 1979, 1983; Dymski 1988; Graziani 1989; Minsky, Nell, and Semmler 1991; Minsky 1993; Keen 1995; Dow 1997; Werner 1997; Rochon 1999; Palley 2002; Fontana and Realfonzo 2005; Carney 2012; Fullwiler 2013; Werner 2014; Schumpeter 1934; Holmes 1969).

But we’re used to being ignored. Mainstream economists reject our papers when we submit them to their journals, and they never read our journals or books. We were resigned to being right, but not taken seriously at the same time.

Then in 2014, a miracle occurred: the Bank of England published a paper that supported our realistic analysis, and rubbished the mainstream myths. Entitled “Money creation in the modern economy“, it began with the declaration that:

Money creation in practice differs from some popular misconceptions — banks do not act simply as intermediaries, lending out deposits that savers place with them, and nor do they ‘multiply up’ central bank money to create new loans and deposits. (McLeay, Radia, and Thomas 2014, p. 14. Emphasis added)

It took direct aim at textbook writers like Mankiw with the statement that:

The reality of how money is created today differs from the description found in some economics textbooks:

- Rather than banks receiving deposits when households save and then lending them out, bank lending creates deposits.

- In normal times, the central bank does not fix the amount of money in circulation, nor is central bank money ‘multiplied up’ into more loans and deposits.” (McLeay, Radia, and Thomas 2014, p. 14. Emphasis added)

I remember how much this paper excited me when it first came out: surely the textbook writers couldn’t ignore the Bank of England? I felt the same thrill in 2017 when the Bundesbank came out with a very compatible paper, in which it declared that:

It suffices to look at the creation of (book) money as a set of straightforward accounting entries to grasp that money and credit are created as the result of complex interactions between banks, non-banks and the central bank. And a bank’s ability to grant loans and create money has nothing to do with whether it already has excess reserves or deposits at its disposal. (Deutsche Bundesbank 2017, p. 13. Emphasis added)

We monetary rebels now had two central banks on our side, opposing the textbook writers, and over time many other Central Banks also joined the fray. Surely now, textbook writers would be forced to change their tune?

Well bollocks to that, as Mankiw’s post on April 5th of this year showed. Entitled “The Importance of Teaching Fractional Reserve Banking“, it was written as if these Central Bank refutations of the Money Multiplier model hadn’t been written. I certainly doubt that Mankiw has read them.

In his post, Mankiw recounted a conversation with a fellow mainstream economist who “does not teach the students about money creation under fractional reserve banking”—and not because it’s a fallacy, but because he believes it’s “an unnecessary technicality”. Mankiw then defended the false theory on the basis that it explains how “a lower interest rate on reserves increases bank lending and expands the money supply by increasing the money multiplier”, and that it’s necessary to teach “the traditional pedagogy about how banks influence the money supply … if students are to understand the economics of inflation”.

“The traditional pedagogy”, as Mankiw puts it, is no more necessary for students of economics to learn than it is necessary for students of astronomy to learn Ptolemy’s Earth-centric view of the cosmos before they can understand the Copernican system. It’s a fallacy, it belongs in the garbage bin of science, and its continued presence in mainstream economics textbooks is a major reason why mainstream economists don’t understand money, or inflation, or the causes of financial crises.

I’d long ago given up on persuading the mainstream to see reason on this any many other issues, but this ludicrous blog post by Mankiw, and the Twitter conversation initiation by Jason Furman that alerted me to it, was a real “aha moment” for me: why bother trying to reason with these people? They get hit in the face by a wet fish dose of reality, the wet fish is wielded by someone they normally listen to, and yet they continue on regardless with their fantasies.

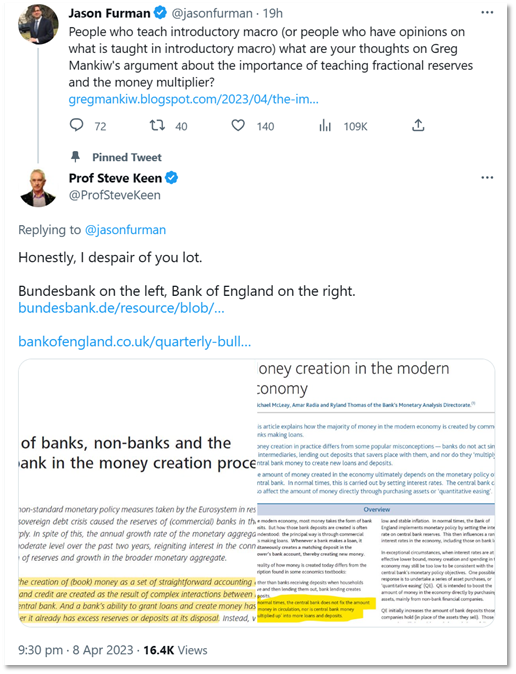

Figure 1: The tweet that alerted me to Mankiw’s blog post, and my acerbic reply

There’s just no point talking with them: they won’t listen to anything that disturbs their paradigm in any way. But they obviously dominate the training of economists: it’s as if the academic astronomy departments were still teaching students to believe in crystalline spheres, equants and epicycles, while Elon Musk and friends were using Newton’s and Einstein’s math to shoot for the stars.

So, what to do? By sheer happenstance, I have started teaching my alternative approach to economics in an online course for which I’m charging US$500. The main reason to charge for it is that most of the money goes to a marketing firm that is motivated by the money to reach a far larger audience than I could ever hope to reach by teaching my ideas for free here on Substack and Patreon. Their early marketing methods were annoying—and I apologise for that—but they’re learning about my audience, and improving their messaging over time.

I give ten lectures over ten weeks, which at $50 a lecture is pretty good value. It’s certainly better for your brain (and your pocket!) than paying for a degree in economics that teaches you the fantasies that Mankiw and other mainstreamers peddle. If you’d like to experience these lectures (with a money-back guarantee if you ask for a refund within the first 30 days), click on this link:

https://start.profstevekeen.me/products/email-am-rebel-economist

Tell them Greg sent you.

Carney, John. 2012. “What Really Constrains Bank Lending.” In NetNet, edited by John Carney. New York: CNBC.

Deutsche Bundesbank. 2017. ‘The role of banks, non- banks and the central bank in the money creation process’, Deutsche Bundesbank Monthly Report, April 2017: 13-33.

Dow, Sheila C. 1997. ‘Endogenous Money.’ in G. C. Harcourt and P.A. Riach (eds.), A “second edition” of The general theory (Routledge: London).

Dymski, Gary A. 1988. ‘A Keynesian Theory of Bank Behavior’, Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 10: 499-526.

Fontana, Giuseppe, and Riccardo Realfonzo (ed.)^(eds.). 2005. The Monetary Theory of Production: Tradition and Perspectives (Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke).

Fullwiler, Scott T. 2013. ‘An endogenous money perspective on the post-crisis monetary policy debate’, Review of Keynesian Economics, 1: 171–94.

Graziani, Augusto. 1989. ‘The Theory of the Monetary Circuit’, Thames Papers in Political Economy, Spring: 1-26.

Holmes, Alan R. 1969. “Operational Constraints on the Stabilization of Money Supply Growth.” In Controlling Monetary Aggregates, edited by Frank E. Morris, 65-77. Nantucket Island: The Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.

Keen, Steve. 1995. ‘Finance and Economic Breakdown: Modeling Minsky’s ‘Financial Instability Hypothesis.”, Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 17: 607-35.

Mankiw, N. Gregory. 2012. Principles of Macroeconomics, 6th edition (South-Western, Cengage Learning: Mason).

McLeay, Michael, Amar Radia, and Ryland Thomas. 2014. ‘Money creation in the modern economy’, Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin, 2014 Q1: 14-27.

Minsky, Hyman P. 1993. ‘On the Non-neutrality of Money’, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Quarterly Review, 18: 77-82.

Minsky, Hyman P., Edward J. Nell, and Willi Semmler. 1991. ‘The Endogeneity of Money.’ in, Nicholas Kaldor and mainstream economics: Confrontation or convergence? (St. Martin’s Press: New York).

Moore, Basil J. 1979. ‘The Endogenous Money Supply’, Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 2: 49-70.

———. 1983. ‘Unpacking the Post Keynesian Black Box: Bank Lending and the Money Supply’, Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 5: 537-56.

Palley, Thomas I. 2002. ‘Endogenous Money: What It Is and Why It Matters’, Metroeconomica, 53: 152-80.

Rochon, Louis-Philippe. 1999. ‘The Creation and Circulation of Endogenous Money: A Circuit Dynamique Approach’, Journal of Economic Issues, 33: 1-21.

Schumpeter, Joseph Alois. 1934. The theory of economic development : an inquiry into profits, capital, credit, interest and the business cycle (Harvard University Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts).

Werner, R. 1997. ‘Towards a new monetary paradigm: a quantity theorem of disaggregated credit, with evidence from Japan’, Kredit und Kapital, 30: 276-309.

Werner, Richard A. 2014. ‘Can banks individually create money out of nothing? — The theories and the empirical evidence’, International Review of Financial Analysis, 36: 1-19.