In my previous post “It’s not a Deficit, it’s a Fiat” (which, like this post, is open access on Patreon and Substack), I showed that the so-called “Deficit” is actually government creation of “Fiat” money. If you haven’t read that post yet, read it now and come back to this one later.

In that post, I rejected the use of the word “Deficit” to describe government spending in excess of taxation, because mainstream economists have made it a pejorative word. Rather like the Pigs in Animal Farm, they declare that “Deficit BAD! Surplus GOOD”, when a deficit for one party in a financial system necessarily requires an identical surplus for another. What a government “deficit” actually does is create “Fiat” money for the non-government sectors of the economy, and from now on I’m going to use that word—Fiat—to describe the gap between government spending and taxation.

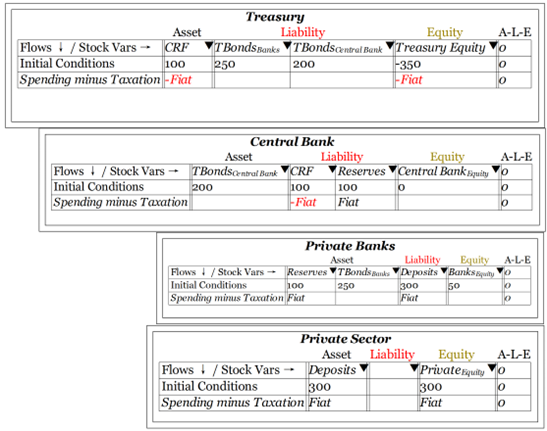

This post starts where that one ended, with the full 4-sector accounting of how the government, when it spends more than it collects in taxes, creates money for the private sector—as shown in Figure 1 here. The key point is that negative entry for Fiat in the Treasury’s Assets causes an identical positive entry in the private sector’s Assets: this is how a government creates Fiat money.

Figure 1: The basics of how a government creates Fiat money

What Figure 1 lacks is an explanation of government “debt”—which is another misnomer, since it doesn’t involve borrowing from banks at all, but rather banks swapping one Asset (Reserves) for another (Treasury Bonds, or TBonds for short).

I’m going to show why by starting with an operation which, in most countries in the world, is illegal: the Central Bank buying bonds directly from the Treasury. This operation is illegal for the same reason that smoking marijuana is illegal in most countries in the world, while drinking alcohol is not. It’s not because the former is more dangerous than the latter, but because legislators followed conventional wisdom rather than scientific research, and banned the safer drug while making the more dangerous one legal.

If the government doesn’t sell bonds, then what will happen is obvious from Figure 1: a sustained Fiat (“Deficit” for those who still haven’t got the memo) will drive the CRF (the “Consolidated Revenue Fund”, the Treasury’s account at the Central Bank) into overdraft. Without bond sales, there’s only one entry in the CRF account, and it’s negative.

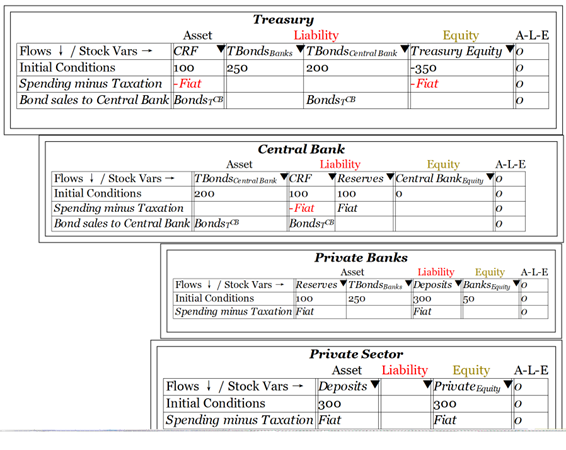

On the other hand, if the Treasury sells bonds to the Central Bank, as shown in Figure 2, then there is a positive entry in the CRF—the proceeds of bond sales—as well as a negative. The CRF can then remain positive. In fact, if bond sales precisely equal Fiat, then the CRF will remain constant.

Figure 2: Treasury Bond sales to the Central Bank

Which situation is better: no bond sales and the CRF going into overdraft, as in Figure 1, or bond sales and the CRF remaining positive, as in Figure 2? Personally, I prefer Figure 2, since then the CRF, which is the Treasury’s deposit account at the Central Bank, remains positive, like deposit accounts in private banks. It would feel strange that a crucial deposit account in the overall financial system is negative while all others are positive, which is the case for Figure 1.

But that’s all that is involved here: it’s just a feeling. Practically, there is no significant difference between Figure 1 and Figure 2: in both cases, the government creates money for the private sector by going into negative equity itself, to a level that is precisely equal to the positive equity it creates for the private sector. This is simply how a fiat currency works.

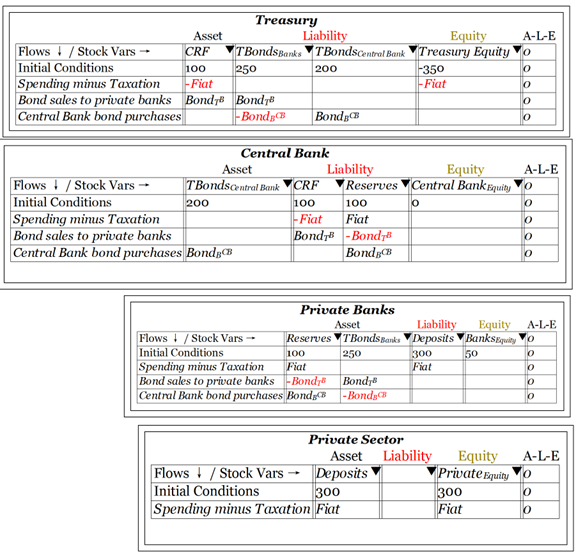

Unfortunately, stupid laws mean that neither Figure 1 nor Figure 2 is legal. Instead, just like a stoner is forced by stupid laws to buy his dope from a dealer, the Central Bank is forced by stupid laws to buy Treasury Bonds from Private Banks. What actually happens in practice is shown in Figure 3: the Treasury sells to Primary Dealers, and the Central Bank buys off the Dealers.

Figure 3: Treasury sells to (Primary) Dealers, the Central Bank buys off Dealers

“Primary Dealers” is a very apt label for private banks, given that they function like drug dealers selling to drug consumers today. They only have a market because stupid laws enable their trade.

The end result of this process is, potentially, equivalent to the direct sale of Bonds by the Treasury to the Central Bank—if the Central Bank bought all the Bonds sold to the private banks. It certainly has no impact on the core fact that the government creates Fiat money by spending more than it gets back in taxation, which in turn increases private sector bank deposit accounts by precisely the same amount.

I haven’t shown interest payments yet for two reasons. Firstly, I’m making the false assumption that the Central Bank buys all the bonds. This is something it’s entirely capable of doing, but normally it doesn’t. Secondly, in most countries, the Treasury is not required to pay interest on bonds held by the Central Bank—and in countries where it is so required, the Treasury receives most of that back, because technically the Treasury owns the Central Bank.

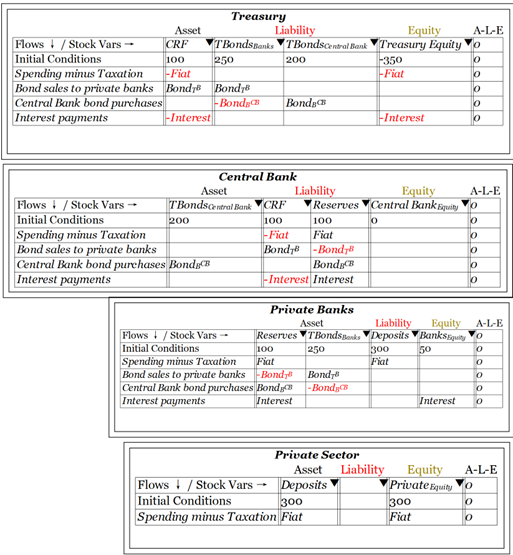

Removing this assumption means that the Treasury has to pay interest on the bonds owned by the private banks—and that gets us to Figure 4, which is the real-world situation (minus one detail of the real world, that private banks sell a lot of the bonds they buy to NBFIs: non-bank financial institutions).

Figure 4: Interest payments on bonds create net worth for the banks

This changes the situation shown in Figure 1 in one important respect: as well as the Fiat creating money for the private non-bank sector, interest payments on bonds create money for the banking sector.

The reason that I describe the sale of bonds to banks as a gift is that, because of this sale, the Government pays the banks an income stream which it could easily avoid by having the Central Bank buy all the bonds issued by the Treasury.

Why should the government bestow this gift on the banks? One good reason is that the interest payments compensate the private banks for the costs they incur by running the economy’s payments system. Without interest on government-created money, the banks would have to profit solely from their dealings with the non-bank public: from charging interest on private debt, fees on depositors, etc. They do that anyway of course, but the higher the income banks make directly from the government, the less is the pressure on them to entice the non-bank public into debt.

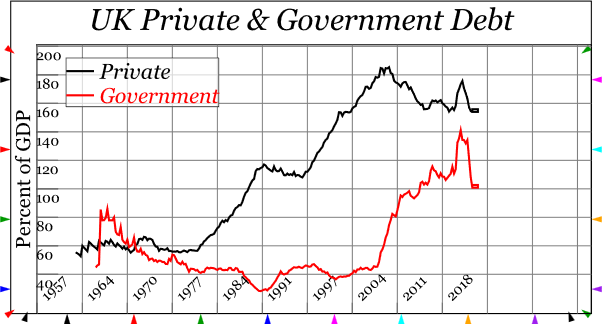

The UK provides a striking example of how the erroneous obsession with reducing government debt—which, to labour the point, reduces the amount of Fiat-based money in the economy—encouraged banks to create private debt to compensate for the fall in their income from the government. Prior to 1980, private debt in the UK was normally below 70% of GDP, and stable. After then, it more than trebled—and this started at a time of high and rising official and private interest rates.

Figure 5: UK Private debt took off when government debt fell & banks were allowed to lend for house purchases

Two causal factors can be identified: the decline in private sector holdings of government bonds relative to GDP, and Thatcher’s decision to allow banks to lend for house purchases (before Thatcher, building societies had an effective monopoly on mortgage issuance in the UK). The former reduced the income of banks substantially, the latter opened up a market for private debt that banks took full advantage of—setting off a house price bubble in the process.

If we had people in charge of the monetary system who actually understood how money works, then private debt, not government debt, would be kept low, the Deficit Fiat would be kept at a level commensurate with the needs of the private sector for money for commerce and savings, and the finance sector would be kept in check.

Instead, with the anti-government debt obsession, we have inadequate government spending on vital services, inadequate amounts of Fiat money in circulation, and the Dealers rather than the authorities, are in charge of the joint. The “War on Deficits Fiat” has been about as successful as the “War on Drugs”.