As I say in the first video in this short series, “come for the clickbait, stay for the education”. No, this post is not money-making advice: it’s telling you how money is actually made, by both banks and the government, using my Minsky software.

Firstly, here are the videos. If you’re a visual learner, you may prefer them to this post:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4tXW1hnqifo

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QcwPGLgYrwQ

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-of4i2vp77o

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nw5ePEyxoOU

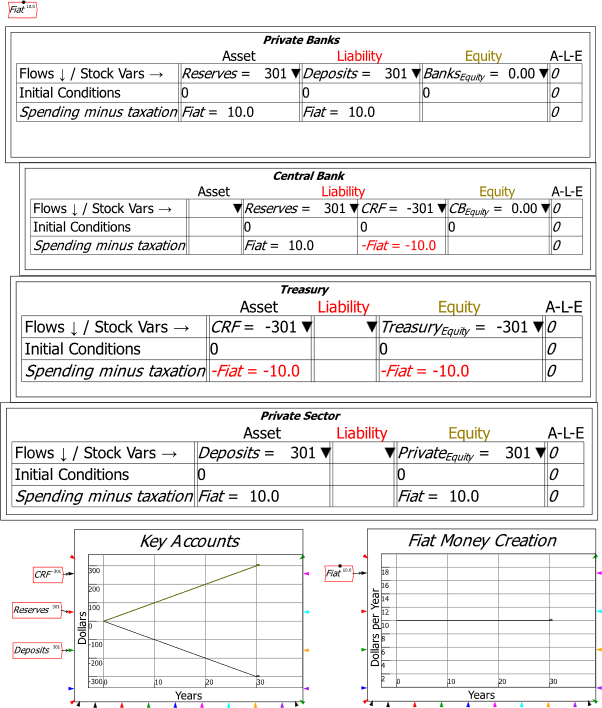

A Pure Credit Economy

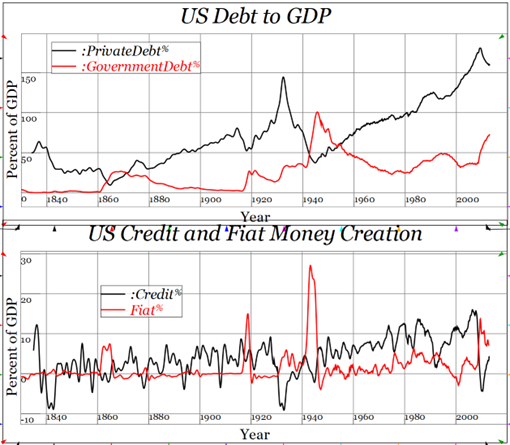

I start with a model of a pure credit economy—one in which there is no government. Though such a thing has never existed, it’s approximately the situation of 19th century America, when government debt never exceeded 26% of GDP (even during the Civil War), the government normally ran a balanced budget or a surplus, and government spending was normally under 10% of GDP—see Figure 1.

Figure 1: Private & Public Debt and money creation since 1830

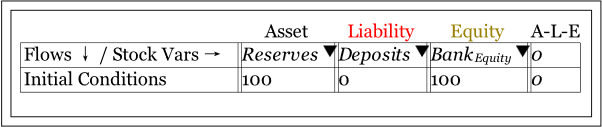

A bank must have positive equity: the value of its (short-term) assets much exceed the value of its (short term) liabilities. If you take a bank which has just been established, it will have assets, but no liabilities, and hence positive equity equal to its Assets. This initial position is shown in Figure 1. This bank’s assets are listed as “Reserves”, it has no liabilities, so its Equity starts equal to its Assets.

Figure 2: A bank must start with, and maintain, positive equity

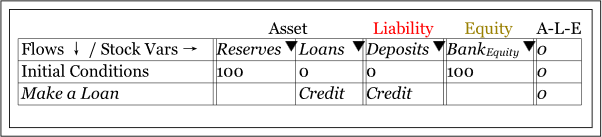

A bank creates money by issuing loans. It simply adds the amount Credit dollars per year to its depositors, and recording that much additional debt for them as well. This is shown in Figure 2—and notice that Reserves play no role at all.

Figure 3: Creating Loans and Deposits simultaneously

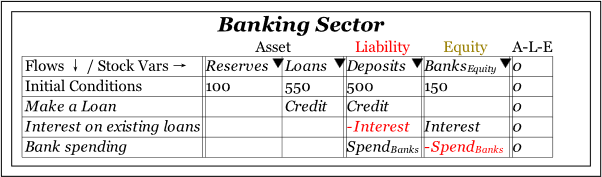

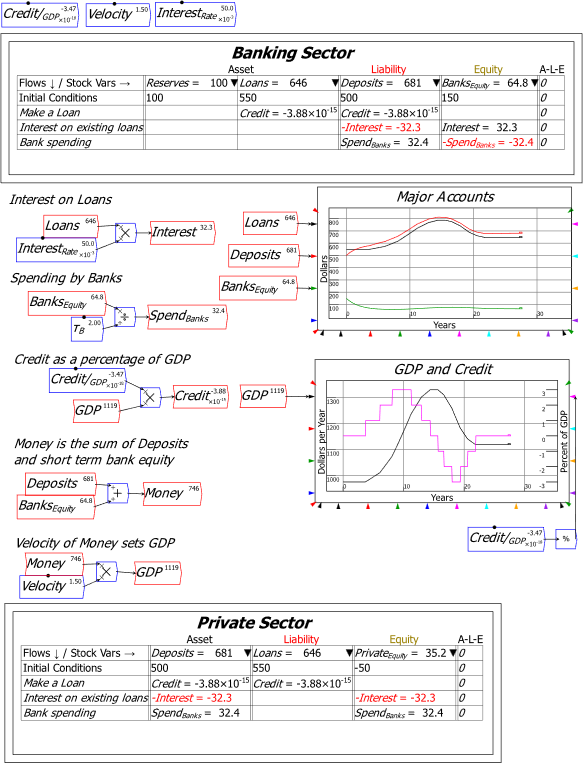

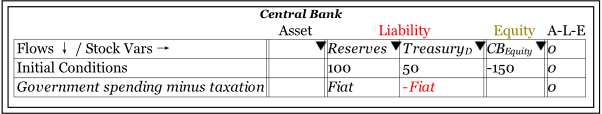

This applies at the aggregate level as well as at the individual bank, so I now consider the aggregate, economic level. Borrowers pay interest on outstanding debt, and banks purchase goods and services from the non-banks. That gives us Figure 4.

Figure 4: Interest payments and bank spending

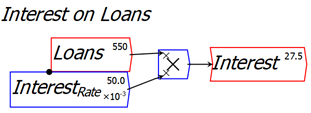

This is enough to start modelling a pure credit economy in Minsky. Minsky uses flowcharts to define mathematical relationships. The most obvious one here is that Interest equals Loans times the rate of interest. With an initial level of loans of $550 billion in Figure 4, and an interest rate of 5 percent per year, Interest payments start at $27.5 billion—see Figure 5.

Figure 5: Defining the flow “Interest”

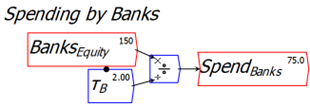

I relate spending by banks to the amount of money they hold—their short-term equity—using the engineering concept of a “time constant”. This basically asks the question “how many years could banks spend without any inflows into their accounts?” This will be a substantial time period, compared to (for example) how long workers could survive without getting any income. I set the time constant for banks to 2 years in Figure 6, so that with initial equity of $150 billion, they will spend $75 billion in the first year.

Figure 6: Spending by banks related to bank short-term equity by a time constant

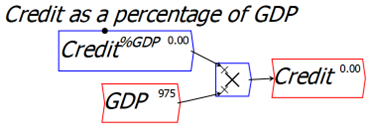

Now I need to define Credit. There are many ways to do this—I could, for example, argue that banks have a target Loans to Equity ratio, and lend till they reach it. But for simplicity, I model credit as a percentage of GDP—see Figure 7.

Figure 7: Credit as a percentage of GDP

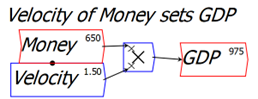

Now I have to define nominal GDP, and again for simplicity I model it as being caused by the turnover of money—a simple “velocity of money” model.

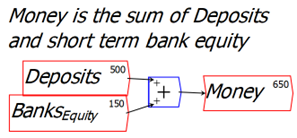

Money is the sum of the Liabilities plus short-term Equity of the banking sector—see Figure 8.

Figure 8: Money as the sum of Deposits plus short term bank equity

The Velocity of Money times Money defines GDP—see Figure 9.

Figure 9: Money times Velocity determines nominal GDP

With those definitions, I can model what happens to nominal GDP as credit rises and falls. Positive credit increases both the money supply and GDP; negative credit causes the money supply and GDP to fall.

Figure 10: A pure credit economy

Did you notice anything unconventional in the above explanation? Reserves, which play a pivotal role in the mainstream model of bank lending, played no role at all here. As I explain in “The Dead Parrot of Mainstream economics”, banks can’t “lend from Reserves” (you can read this post on Substack or Patreon). Instead, Reserves play a crucial role in the next aspect of money creation: government deficits.

A Pure Fiat Economy

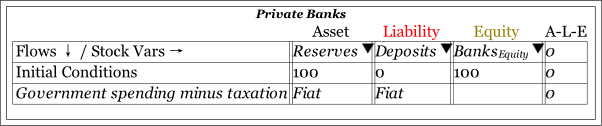

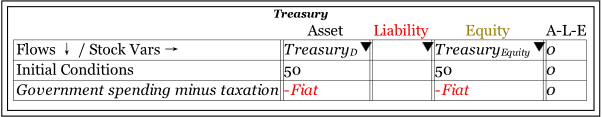

A pure fiat money economy is as much of an abstraction as a pure credit economy, but it lets us isolate the key factors in money creation by governments. This is shown in Figure 11: when a government spends more than it gets back in taxation, it adds Fiat dollars per year to Deposit accounts. That is creating money, just as bank lending creates money, but with one critical difference: the bank asset that is created along with Deposits is Reserves, rather than Loans.

Figure 11: The absolute basics of government money creation

Reserves, which played no role in the model of a pure credit economy, play a central role here. As is well known—even by Neoclassical economists—Reserves are a liability of the Central Bank. Therefore, we have to include the Central Bank to properly model government money creation, and this shows that the increase in Reserves is caused by a transfer of funds from the Treasury’s accounts at the Central Bank, as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12: The Central Bank’s main Liabilities are Reserves and the Treasury’s Deposit account

Finally, we need to look at the Treasury’s books: where does it get the funds? Figure 13 shows the source: the Treasury doesn’t “get” the funds from anywhere: it simply creates them by going into negative equity.

Figure 13: Treasury creates the funds by going into negative equity

I know lots of people will have a “that’s not right” response to this, and in sense that’s partially correct: it’s not right, it’s also “might”. The whole idea of a fiat currency is that the power controlling a nation, the government, can declare that its liabilities are to be used as the form of money in the domain it controls. It therefore needs to create those liabilities, and a deficit—spending more than it takes back in taxation—is the means by which it does that.

Furthermore, its liabilities become the asset of the non-governmental sectors, which is easily seen by looking at the economy from the private sector’s point of view—see Figure 14. The negative equity of the government creates the identical positive equity for the private sector. Therefore, rather than being a “bug” of the system, it is a critically important feature: negative equity for the government is a pre-requisite for the existence of a fiat currency.

Figure 14: The private sector’s positive equity is created by the government’s negative equity

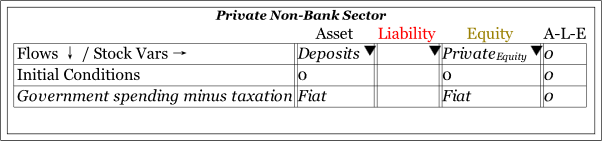

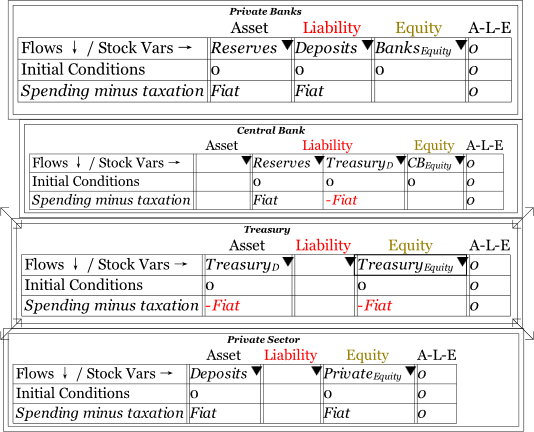

The full picture of government money creation by fiat is shown in Figure 15, and it makes it obvious that the negative equity for the government is the positive equity for the private sector. I’ve set all accounts to zero so that I can show in the next figure that the government can, effectively, create a monetary economy from nothing: whereas the banking sector needs to have positive equity to function, a government can hypothetically start from zero and establish a monetary economy.

Figure 15: The 4 primary sectors of a fiat economy

In Figure 16, I have the government creating $10 (billion) of fiat money per year, by spending $10 billion more than it takes back in taxes. Over 30 years, it creates negative equity for itself of $300 billion, and identical positive equity for the private sector.

Figure 16: Fiat creation of $10 (billion) a year creates money and positive equity for the private sector

I’ve deliberately omitted government bonds until now, because I want to emphasise the fundamental point that, whereas a bank creates money by expanding its assets and liabilities equally, a government creates money by creating negative equity for itself, and identical positive equity for the non-government sector. Bonds play no role in that. But if a government doesn’t issue bonds, then it wears its negative equity on its account at the Central Bank: notice that the Treasury’s account at the Central Bank goes into overdraft. Most governments have passed laws to prevent this: they require the Treasury to maintain a positive balance in its account at the Central Bank.

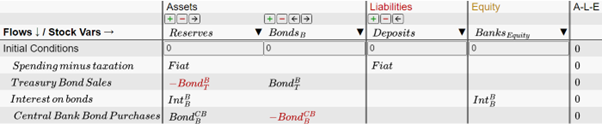

Figure 17 shows this legislatively required situation from the point of view of the banking sector: government spending in excess of taxation creates Fiat money; the government issues bonds equivalent to the amount of Fait money created, plus interest on outstanding bonds; and the Central Bank, in its “Open Market Operations” with private banks, can also purchase bonds as assets for itself on the secondary market (since the same laws also normally ban the Central Bank from buying bonds directly from the Treasury).

Figure 17: Bond sales, interest on bonds and Central Bank bond purchases

This only substantive difference this makes to the situation without bond sales is that, as well as Fiat creating money for the private non-bank sector, interest on bonds owned by the banks creates money (and positive equity) for the banking sector. In addition, because the sale of bonds is required by law to match the excess of government spending over taxation plus the interest paid on bonds owned by the banks, the Treasury’s account at the Central Bank does not go into overdraft.

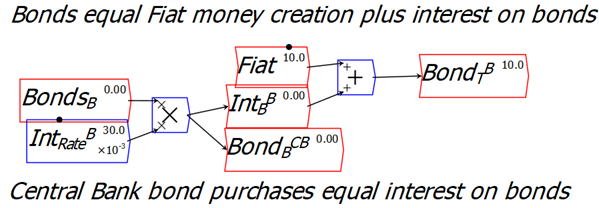

To model this in Minsky, I made bond sales equal to the sum of Fiat plus interest on existing bonds, and had the Central Bank purchase bonds equivalent to the interest on bonds—see Figure 18

Figure 18: Modelling the requirement to sell bonds in Minsky

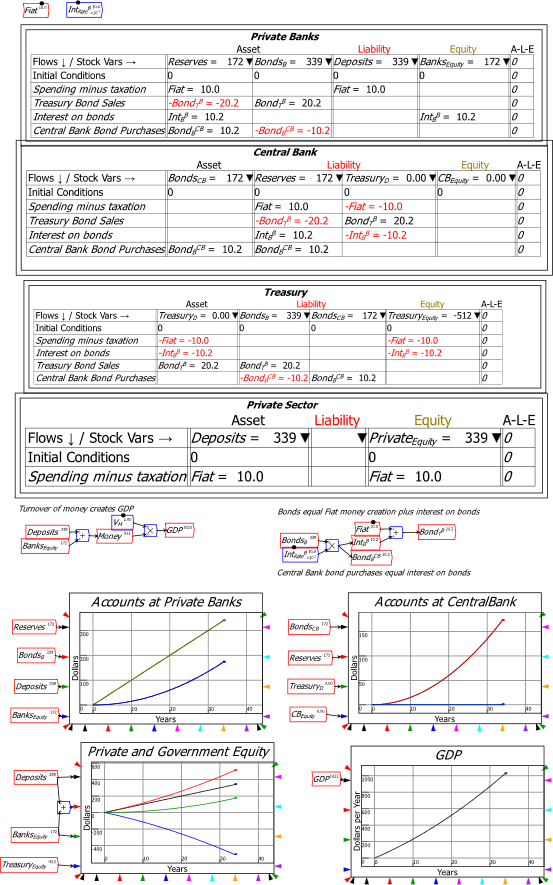

Figure 19 models this with Fiat creation (otherwise misleadingly known as the government deficit) of $10 (billion) per year and a 3% rate of interest on bonds. The outcome is that this creates a growing economy, and generates positive equity for both the private non-banking sector and the banking sector.

Figure 19: A Fiat Currency “lifting itself by its own bootstraps”

Fiat creates money for the non-bank private sector; interest on bonds creates money for the banking sector; and the turnover of money creates GDP. Far from the servicing of government debt being a burden on future generations, as Neoclassical economists claim, the payment of interest on government bonds finances the banking sector while the excess of government spending over taxation creates money and positive equity for the non-bank private sector.

The real world is a mixed fiat-credit system of course, and Minsky can model the two together—which I’ve done in posts before and will doubtless do again. Once you understand this system, the Neoclassical obsession with reducing government debt can be seen for what it is: it is an attitude born of ignorance of the actual system of money creation, and it results in policies that make capitalism malfunction even more so than it would do without their intervention.