If those words mean absolutely nothing to you, please buy The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy now. If your local bookshop is too many planetary systems away, you can buy it from local outlet of the one of the great publishing corporations of Ursa Minor at https://www.amazon.com/Complete-Hitchhikers-Guide-Galaxy-Boxset/dp/1529044197/ or https://www.amazon.com/Hitchhikers-Guide-Galaxy-Douglas-Adams-ebook/dp/B000XUBC2C/. Read at least the first volume immediately, before you continue with this post. You can thank me later.

If you have already read it, and that sentence still doesn’t make sense to you, that’s OK iff (not a misprint) you’ve drunk too many (i.e., more than 1/50th of one) Pan Galactic Gargle Blasters: it’s a known side-effect.

If you have, and it (the title of this post: please pay attention!) still doesn’t make sense, and you haven’t, then shame on you. Go back and read all five volumes in the trilogy now, while drinking a 1/5th of a Pan Galactic Gargle Blaster. You can thank me if and when you sober up.

Where was I? Ah, yes: I am Zaphod Beeblebrox.

Like I am sure many male readers of Douglas Adams’s brilliant novellas, I have often wondered which of the male characters I was most like.

Was I the bumbling Arthur Dent, the human so often surprised by the turn of Galactic—and indeed, interpersonal—events, and permanently attired in a dressing gown? Or Ford Prefect, the poorly named but dashing, cocky and cynical Galactic traveller, bon vivant and researcher for The Guide? Surely, I was not Zaphod Beeblebrox, the reckless, ludicrously gifted and erratically driven inventor of the Pan Galactic Gargle Blaster, Galactic President and the (two-headed) man who stole, on its maiden voyage, the spaceship The Heart of Gold, with its unique and wildly improbable Infinite Improbability Drive?

I’d always leant towards being Ford Prefect. I clearly had his knack for getting into trouble but somehow surviving, and we shared the same respect for authority—which is to say, none. But as my life unfolds, so have the similarities to Zaphod. The clincher was this bot (that was a misprint, but I like it, so it’s staying) of dialog as the Heart of Gold orbited above what Zaphod insisted was the fabled planet-building planet of Magrathea, which Ford insisted was a myth:

‘You’re crazy, Zaphod,’ he was saying, ‘Magrathea is a myth, a fairy story, it’s what parents tell their kids about at night if they want them to grow up to become economists, it’s . . .’

Oh dear. There was Douglas Adams saying, as only he can, that economics is a fantasy.

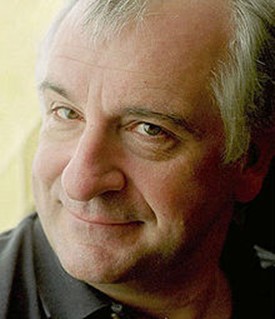

Figure 1: The one, the only, the late and oh-so-much lamented Douglas Adams

I could have remained Ford in my own mind at that point, except that the story continued on to ponder Zaphod’s two heads, their weird mental gifts, and how those gifts had ruled Zaphod’s unruly life:

‘I freewheel a lot. I get an idea to do something, and, hey, why not, I do it. I reckon I’ll become President of the Galaxy, and it just happens, it’s easy. I decide to steal this ship. I decide to look for Magrathea, and it all just happens. Yeah, I work out how it can best be done, right, but it always works out.’

‘It’s like having a Galactic credit card which keeps on working though you never send off the cheques…’ Zaphod paused for a while. For a while there was silence. Then he frowned and said, ‘Last night I was worrying about this again. About the fact that part of my mind just didn’t seem to work properly. Then it occurred to me that the way it seemed was that someone else was using my mind to have good ideas with, without telling me about it’.

That has been my life. Weird ideas pop into my head that turn out to be right, before I am able to prove that they are, and with me having no idea how they came about. I did not deduce them from any set of logical premises, they simply turned up in my head, largely fully formed. Often, they occurred to me when I wasn’t working—the last one occurred on a late-night trip back from the bathroom during an interrupted sleep. In Paris.

The first was that Marx’s philosophy contradicted his economics, which led to the conclusion that there was no “scientific” necessity for socialism (Keen 1993a, 1993b). The Labor Theory of Value, which is an article of faith for Marxists, was wrong, and the “Tendency for the Rate of Profit to Fall”, which is critical to the notion that capitalism must give way to socialism, was false.

The second was that the “Hicks Hansen Samuelson Second Order Difference Equation” model of the trade cycle was based on an economic fallacy of equating desired (“ex-ante”) investment to actual (“ex-post”) savings (Keen 2020, 2000). There is no theory of economics that says they are equal: Keynes’s “Savings=Investment” is based on equating actual savings to actual investment (“ex-post” to “ex-post”). I therefore knew that Minsky’s own attempt at a mathematical model of his own “Financial Instability Hypothesis” must be wrong, since he built it by turning a parameter in that model into a variable. That in turn led to my decision to do my PhD on building a proper mathematical model of the Financial Instability Hypothesis (Keen 1995).

There have been about ten all up. The last one I’ve published came from the insight that “labour without energy is a corpse, capital without energy is a sculpture” (Keen, Ayres, and Standish 2019), which let me finally show that energy was an integral aspect to production—when both Neoclassical and Post Keynesian “production functions” ignore energy.

Occasionally I knew a stimulus to the thought, but the formation of the thought itself was and remains a mystery. Whether I’ll have any more remains a mystery too, though perhaps having one more too many Pan Galactic Gargle Blasters might resolve that mystery in the negative.

It’s worth a try…

Keen, Steve. 1993a. ‘The Misinterpretation of Marx’s Theory of Value’, Journal of the history of economic thought, 15: 282-300.

———. 1993b. ‘Use-Value, Exchange Value, and the Demise of Marx’s Labor Theory of Value’, Journal of the history of economic thought, 15: 107-21.

———. 1995. ‘Finance and Economic Breakdown: Modeling Minsky’s ‘Financial Instability Hypothesis.”, Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 17: 607-35.

———. 2000. ‘The Nonlinear Economics of Debt Deflation.’ in William A. Barnett, Carl Chiarella, Steve Keen, Robert Marks and H. Schnabl (eds.), Commerce, complexity, and evolution: Topics in economics, finance, marketing, and management: Proceedings of the Twelfth International Symposium in Economic Theory and Econometrics (Cambridge University Press: New York).

———. 2020. ‘Burying Samuelson’s Multiplier-Accelerator and resurrecting Goodwin’s Growth Cycle in Minsky.’ in Robert Y. Cavana, Brian C. Dangerfield, Oleg V. Pavlov, Michael J. Radzicki and I. David Wheat (eds.), Feedback Economics : Applications of System Dynamics to Issues in Economics (Springer: New York).

Keen, Steve, Robert U. Ayres, and Russell Standish. 2019. ‘A Note on the Role of Energy in Production’, Ecological Economics, 157: 40-46.

Did you happen to have one head two arms and call yourself Phil?