I have just commenced a six-month research project at the Budapest Centre for Long-Term Sustainability (https://bc4ls.com/), and one of my allotted tasks is to write a 30,000 word book. With apologies to my good friend Blair Fix, my working title echoes that of his blog (https://economicsfromthetopdown.com/): “Rebuilding Economics from the Top Down”.

I start with the hubris of mainstream economics prior to the Global Financial Crisis. The next instalment will discuss their failed attempt at soul-searching after the crisis, which has resulted in models that failed to anticipate the Global Financial Crisis still dominating the profession today.

I will post draft chapters as I complete them on my Patreon (https://www.patreon.com/ProfSteveKeen) and Substack (https://profstevekeen.substack.com/) pages. Please consider signing up to one or the other, so that I can continue to make my research freely available. My intention is to post at least one chapter each week for the next three months.

The Magnificent Failure of Mainstream Economics

For the last fifty years, the development of economics has been driven by the desire to derive macroeconomic analysis directly from microeconomic theory. This research program was a theoretical success and a practical failure.

Modern macroeconomic modelling, initially in the form of Real Business Cycle (RBC) and later Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DSGE) models, is firmly based on the utility and profit maximizing principles of microeconomics, and in particular, the growth model developed by Frank Ramsey in 1928 (Ramsey 1928). The success of this process of derivation, combined with the economic conditions of the last decade of the 20th century and the first half-decade of the 21st, led mainstream economists to believe that they had found the economic “Holy Grail”: a well-grounded theory of economics which also enabled economists to manage the economy successfully.

Robert Lucas, one of the key architects of the “microfoundations revolution”, gave a triumphalist perspective on the state of economics in his Presidential Address to the American Economic Association in January 2003:

Macroeconomics was born as a distinct field in the 1940’s, as a part of the intellectual response to the Great Depression. The term then referred to the body of knowledge and expertise that we hoped would prevent the recurrence of that economic disaster. My thesis in this lecture is that macroeconomics in this original sense has succeeded: Its central problem of depression prevention has been solved, for all practical purposes, and has in fact been solved for many decades… Taking U.S. performance over the past 50 years as a benchmark, the potential for welfare gains from better long-run, supply-side policies exceeds by far the potential from further improvements in short-run demand management. (Lucas 2003, p. 1)

A similar triumphalism pervaded policy circles. Ben Bernanke, speaking just 16 months before he became Chairman of the Federal Reserve, declared in October 2004 that:

the low-inflation era of the past two decades has seen not only significant improvements in economic growth and productivity but also a marked reduction in economic volatility, both in the United States and abroad, a phenomenon that has been dubbed “the Great Moderation.” Recessions have become less frequent and milder, and quarter-to-quarter volatility in output and employment has declined significantly as well. The sources of the Great Moderation remain somewhat controversial, but as I have argued elsewhere, there is evidence for the view that improved control of inflation has contributed in important measure to this welcome change in the economy. (Bernanke 2004)

Likewise, economic modellers were confident that their mathematical models of the economy could accurately predict its future behaviour. Though, as I note below, there were some elements of conflict, criticism and scepticism within mainstream academic economics, model builders, who were the dominant faction, were boastfully loud and proud. In June 2007, the authors of the most celebrated DSGE model proclaimed its capacity to out-perform mere econometric techniques, and to forecast the economy’s future path:

Using a Bayesian likelihood approach, we estimate a dynamic stochastic general equilibrium model for the US economy using seven macroeconomic time series. The model incorporates many types of real and nominal frictions and seven types of structural shocks. We show that this model is able to compete with Bayesian Vector Autoregression models in out-of-sample prediction. We investigate the relative empirical importance of the various frictions. Finally, using the estimated model, we address a number of key issues in business cycle analysis: What are the sources of business cycle fluctuations? Can the model explain the cross correlation between output and inflation? What are the effects of productivity on hours worked? What are the sources of the “Great Moderation”? (Smets and Wouters 2007, p. 586).

This confidence rubbed off on international economic bodies, with the OECD entitling the editorial to its June 2007 Economic Outlook report “Achieving further rebalancing”, and declaring that:

the current economic situation is in many ways better than what we have experienced in years. Against that background, we have stuck to the rebalancing scenario. Our central forecast remains indeed quite benign: a soft landing in the United States, a strong and sustained recovery in Europe, a solid trajectory in Japan and buoyant activity in China and India. In line with recent trends, sustained growth in OECD economies would be underpinned by strong job creation and falling unemployment. (Cotis 2007, p. 7)

“Pride”, as the proverb goes, “goeth before destruction, and an haughty spirit before a fall”. Just 2 months after the OECD foresaw “strong job creation and falling unemployment”, and Smets and Wouters crowed about the out-of-sample predictive powers of their DSGE model, less than three years after Bernanke heralded “this welcome change in the economy”, and less than five years after Lucas proclaimed that the “problem of depression prevention has been solved”, the global economy collapsed into the greatest economic crisis since the Great Depression.

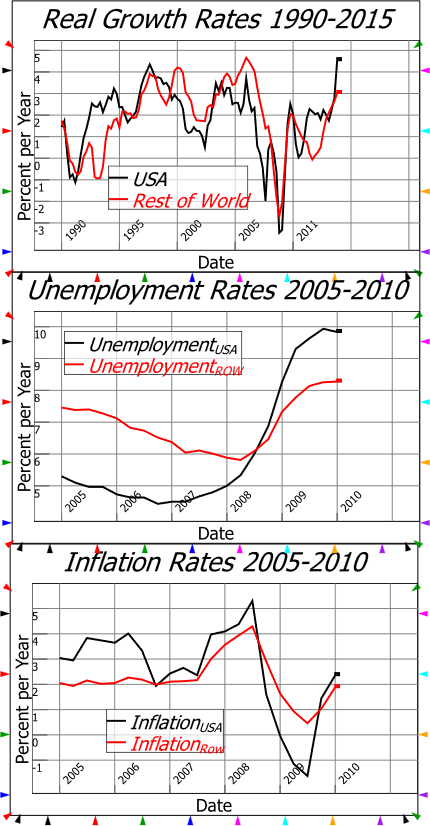

As the top plot in Figure 1 shows, the rate of economic growth crashed from 4.5% per year to minus 3%, the opposite of the “buoyant activity in China and … sustained growth in OECD economies” that the OECD advised was in store for 2008 and 2009. Just as worryingly, the rise in unemployment that always occurs during a recession was accompanied this time by a phenomenon that had not been seen since The Great Depression itself: deflation. Though in the end, in response to significant government policy interventions, the period of deflation was short-lived, it nonetheless occurred: the rate of growth of consumer prices in the USA collapsed from over 5% per year in late 2007 to under minus 1% per year by mid-2009. In stark contrast to Lucas’s confidence that “welfare gains from better long-run, supply-side policies exceeds by far [his emphasis] the potential from further improvements in short-run demand management”, economists who were ill-equipped for the job found themselves desperately trying to boost short-run economic demand.

Figure 1: Growth rates from 1990-2015 for the USA & 25 other major economies

Here they also failed, in comparison to the “Keynesian” economic orthodoxy which preceded them. The hapless President Obama, whose degrees were in political science and law, took the advice of dominant mainstream economics figures—such as Larry Summers, whom he appointed Director of the USA’s National Economic Council, and Timothy Geithner, whom he appointed Secretary of the Treasury—that the way to end the crisis quickly was to pump the banking system full of excess Reserves. This, Obama was assured, would stimulate the economy more rapidly than, for example, putting money directly into the hands of households. Obama lent his oratorical skills to this mainstream economic advice, stating in a speech at Georgetown University in April 2009 that:

although there are a lot of Americans who understandably think that government money would be better spent going directly to families and businesses instead of banks—”where’s our bailout?,” they ask—the truth is that a dollar of capital in a bank can actually result in eight or ten dollars of loans to families and businesses, a multiplier effect that can ultimately lead to a faster pace of economic growth. (Obama 2009. Emphasis added)

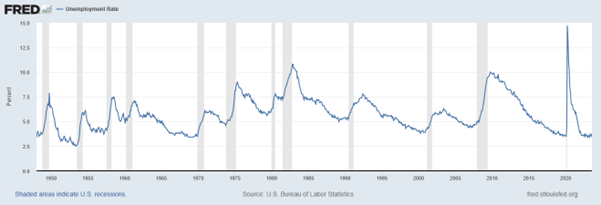

The incredibly brief Covid recession threw into high relief just how wrong this conventional economic advice was. When Covid lockdowns forced people out of work, the government response was to give households immediate financial stimulus—and the recession was over in 2 months. The “Great Recession”, as Americans christened what the rest of the world called the “Global Financial Crisis”, lasted one and a half years, making it the second-longest recession in the USA in the past century. Only the first phase of the Great Depression, from August 1929 till March 1933, lasted longer.

Figure 2: The drawn-out recession of the Global Financial Crisis, versus the almost instantly-over Covid Recession

A theoretical and practical failure as big as this—to have models that did not show that the biggest macroeconomic event in a century was imminent, and to be so unprepared for a crisis that the policies advocated by economists made the recovery worse—did provoke some critical reflection amongst economists. But their reflections lacked any capacity to imagine any other way to build macroeconomics apart from the method that had already failed them.

References

Bernanke, Ben S. 2004. “Panel discussion: What Have We Learned Since October 1979?” In Conference on Reflections on Monetary Policy 25 Years after October 1979. St. Louis, Missouri: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Cotis, Jean-Philippe. 2007. ‘Editorial: Achieving Further Rebalancing.’ in OECD (ed.), OECD Economic Outlook (OECD: Paris).

Lucas, Robert E., Jr. 2003. ‘Macroeconomic Priorities’, American Economic Review, 93: 1-14.

Obama, Barack. 2009. “Obama’s Remarks on the Economy.” In. New York: New York Times.

Ramsey, F. P. 1928. ‘A Mathematical Theory of Saving’, The Economic Journal, 38: 543-59.

Smets, Frank, and Rafael Wouters. 2007. ‘Shocks and Frictions in US Business Cycles: A Bayesian DSGE Approach’, American Economic Review, 97: 586-606.