As Graeber pointed out in Debt: The First 5000 Years, the assumption that money originated in barter is an enduring myth in economics: “First comes barter, then money; credit only develops later” (Graeber 2011, Chapter 2). This myth permeates the discipline, from Adam Smith’s assertion in 1776 that “the propensity to truck, barter, and exchange one thing for another” (Smith 1776, Chapter 2) was an innate characteristic of humans, to modern economics textbooks, like Gregory Mankiw’s Macroeconomics, that argue that an economy without money would be “a barter economy” (Mankiw 2016, p. 82).

Armed with this myth, economists have constructed a fantasy model of capitalism in which money plays no significant role: it is a mere trifle that sensible economists look through, to see the real face of barter lying behind the veil of money. Consequently, mainstream economists ignore banks, debt and money, while credit plays no role in their mathematical models of the macroeconomy.

This is why they not only didn’t see the 2007 Global Financial Crisis coming, but in fact expected 2008 to be a cracker of a year. The OECD’s Economic Outlook in June 2007 trumpeted that “sustained growth in OECD economies would be underpinned by strong job creation and falling unemployment” (Cotis 2007, p. 5).

Yeah, right. Two months after this forecast was published, the biggest economic crisis before Covid-19 and since the Great Depression began.

Why were they so wrong? Because they ignore Graeber’s central message that debt and credit drive the development, and sometimes the collapse, of economies.

Their logic rests, as usual, on a naïve assumption. They assume that banks are simply “intermediaries” between people who save money, and people who borrow money, and therefore that redistributing this money has little effect on economic activity. As ex-Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke put it, “Absent implausibly large differences in marginal spending propensities among the groups … pure redistributions should have no significant macroeconomic effects.” (Bernanke 2000, p. 24).

What the hell does that jargon mean? It means that mainstream economists pretend that banks don’t create money when they lend—something that they can no longer do after The Bank of England categorically said that they do (McLeay, Radia et al. 2014)—or that this doesn’t really matter. A little arithmetic is enough to show they’re wrong, and David was right.

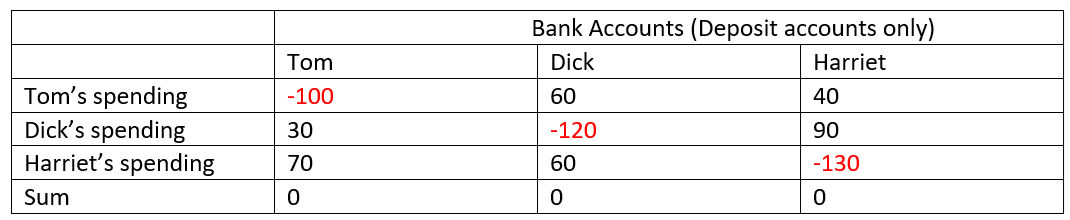

One of the incontrovertible truisms of economics is that your spending is someone else’s income: what is expenditure to you is income to someone else. For simplicity, imagine a three-person economy—Tom, Dick, and Harriet—where Tom spends $60 a year on Dick & $40 a year Harriet, Dick spends $30 a year on Tom and $90 a year on Harriet, and Harriet spends $70 a year on Tom and $60 a year on Dick. Total income and total expenditure in this toy economy, shown in Table 1, is therefore $350 per year.

Table 1

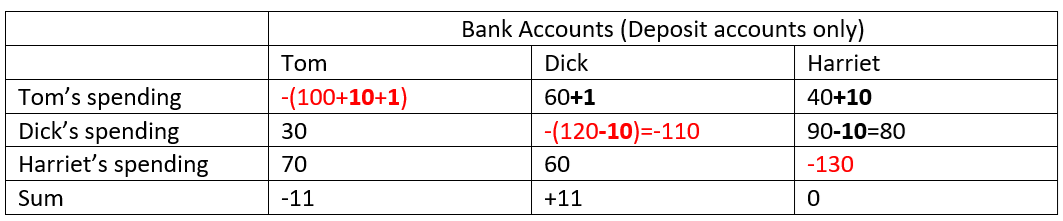

The mainstream economic fantasy that banks are “financial intermediaries”, can be illustrated by imagining that Dick lends $10 to Tom at 10% interest, and Tom uses this to spend another $10 on Harriet, while also having to pay Dick $1 interest. Do the sums on Table 2, and you’ll find that total income and total expenditure is $351: the $1 in interest has turned up as extra expenditure by Tom and income to Dick. But the $10 that Tom borrowed from Dick cancels out: to lend $10 to Tom for him to spend, Dick had to spend $10 less on Harriet.

Table 2

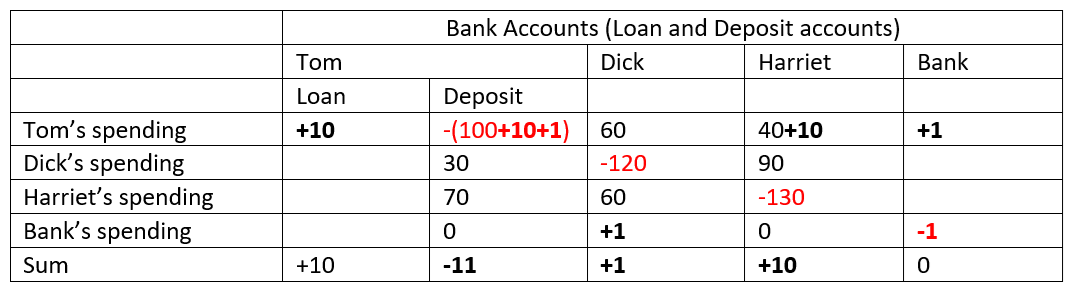

But what if Tom got a loan, not from Dick, but from the bank? This toy economy is closer to the real world. Here, the increase in Tom’s spending power comes from increasing his indebtedness to the bank. The additional $10 spending on Harriet does not come at the expense of Dick’s spending, as in the mainstream economics fantasy, but from the bank loan creating $10 of new money, which Dick then spends on Harriet. Include the bank also spending its $1 in interest income on Dick, and you will find that income and expenditure in this more realistic toy m odel is $361: the credit money that the bank loan created has increased both expenditure (Tom’s, by $10) and incomes (Harriet’s, by $10).

Table 3

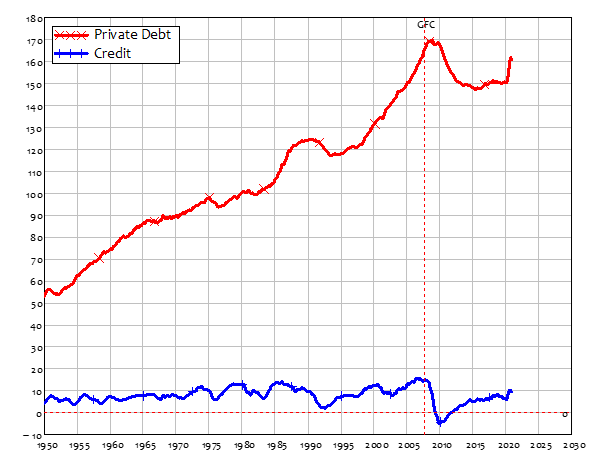

This simple monetarist arithmetic is what mainstream economists are ignoring when they leave banks, debt, and money out of their models. It’s why they have never seen an economic crisis coming, because they ignore what causes it: too much credit during a boom, and credit turning negative during a slump. Because of their fallacious advice to ignore the level of private debt and its growth (credit), policymakers ignored clear signs that a crisis was imminent in 2007. Then credit turned negative for the first time since WWII, and the OECD’s assurance that the world would experience “sustained growth” in 2008 was in tatters.

Figure 1: USA Private Debt and Credit since 1950

One of the great tragedies of 2020 is that David is no longer with us, but mainstream economics still is. We should honor his memory by, as he wished, killing the delusional fantasy that is mainstream economic theory. We should also bring to life the idea he, Michael Hudson and I have championed, of a Modern Debt Jubilee, to free us from our bondage to those who have profited out of this explosion of private debt: free us from those whom Marx aptly called “the Roving Cavaliers of Credit” (Marx 1894, Vol.3, Chapter 33).

Bernanke, B. S. (2000). Essays on the Great Depression. Princeton, Princeton University Press.

Cotis, J.-P. (2007). Editorial: Achieving Further Rebalancing. OECD Economic Outlook. OECD. Paris, OECD. 2007/1: 7-10.

Graeber, D. (2011). Debt: The First 5,000 Years. New York, Melville House.

Mankiw, N. G. (2016). Macroeconomics. New York, Macmillan.

Marx, K. (1894). Capital Volume III. Moscow, International Publishers.

McLeay, M., A. Radia and R. Thomas (2014). “Money creation in the modern economy.” Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin

2014 Q1: 14-27.

Smith, A. (1776). An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Indianapolis, Liberty Fund.