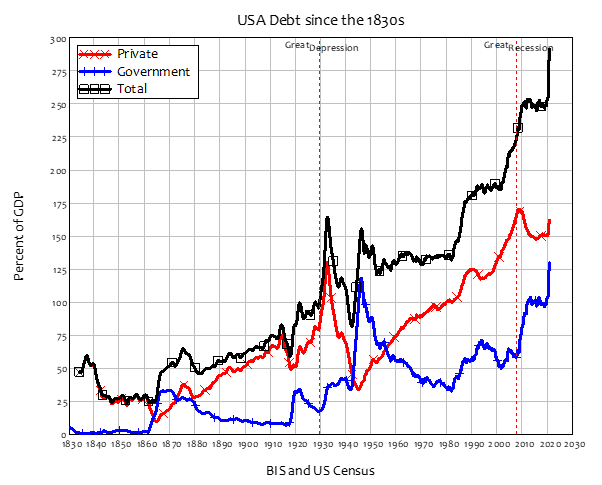

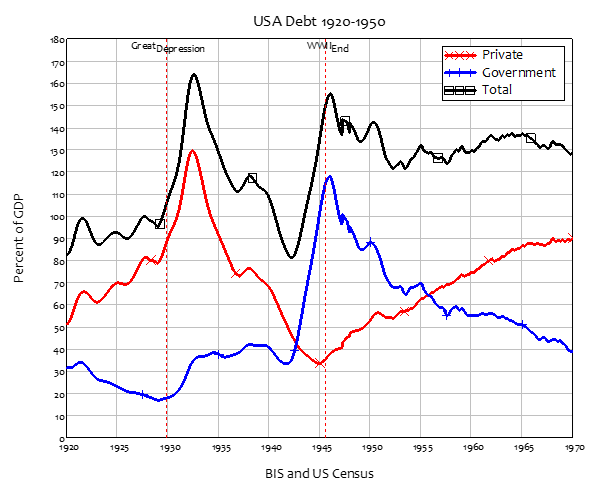

The world is drowning in debt, and the situation is only getting worse—especially after Covid. All types of debt—government, household and corporate—have been rising, relative to GDP, in almost all countries. Debt in the USA is the highest it has ever been—see Figure 1.

Figure 1: USA Debt since the 1830s

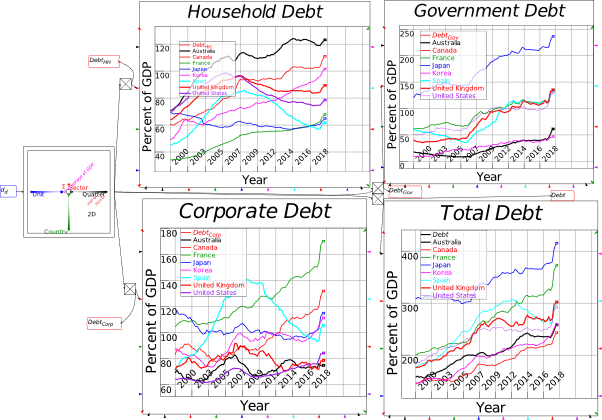

Figure 2 shows a representative sample of major economies since WWII. Australia is the worst on household debt, France on corporate debt, and Japan on both government and total debt. Almost all countries have experienced rising total debt since WWII.

Figure 2: Debt levels for selected economies (BIS Data)

All schools of economic thought think a high level of debt is a problem—they just differ on what sort of debt they worry about.

Neoclassical (and “Austrian”) economists worry about government debt. They claim that government debt “crowds out” private sector investment, by borrowing money that the private sector could have used to invest, and that it saddles future generations with the burden of paying back that debt (Mankiw 2016, pp. 556-57). They don’t worry about private debt, because they see changes in the level of private as simply a transfer of spending power from one private individual to another, and they claim that, unless there are huge differences in their tendency to spend money, the effect on the macro economy should be slight (Bernanke 2000, p. 24).

Post-Keynesian (and “MMT”) economists worry about private debt. They claim that bank lending creates money, and this adds to demand, directly affecting the macro economy. Financial crises are caused by too high a level of private debt, followed by credit—the change in debt—turning negative (Keen 2020). They don’t worry about government debt, because they point out that the government “owns its own bank”, and can create the money needed to pay interest on its debt, so long as it is denominated in its own currency (Kelton 2020).

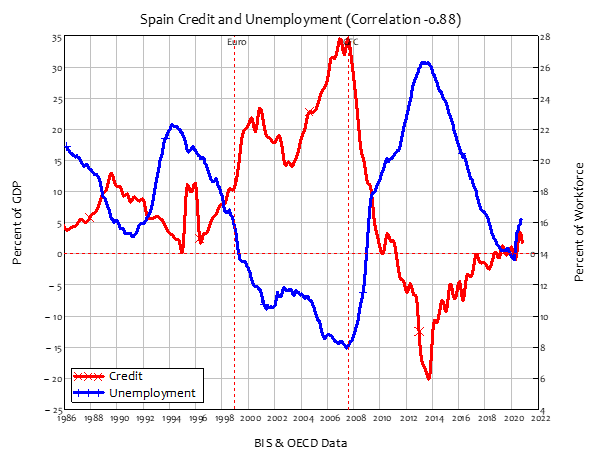

In 2014, The Bank of England came down on the side of the Post Keynesians in this dispute (McLeay et al. 2014): contrary to what economic textbooks argue, bank lending creates money. This new money is borrowed in order to be spent, so that new private debt adds to aggregate demand, driving both GDP (see Figure 3) and asset prices (see Figure 4 and Figure 5). The primary explanation for the savage decline in the Spanish economy from 2008 till 2014 was the plunge in credit—the change in private debt—from plus 35% of GDP in 2008 to minus 20% in 2014.

Figure 3: Credit and Unemployment in Spain

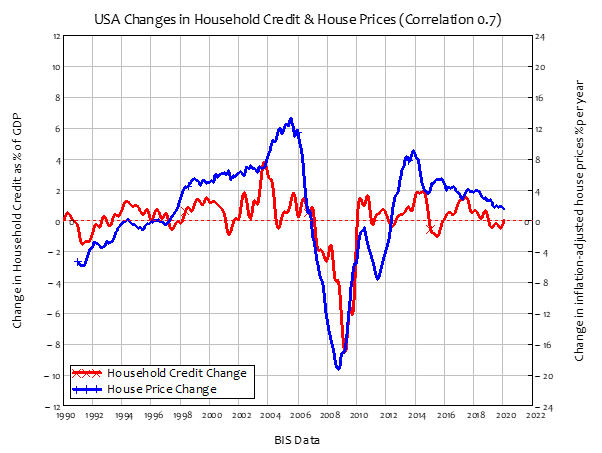

The boom, bust and recovery of American house prices between 1997 and now was driven by changes in the level of household credit—see Figure 4.

Figure 4: USA Household Credit and House Prices

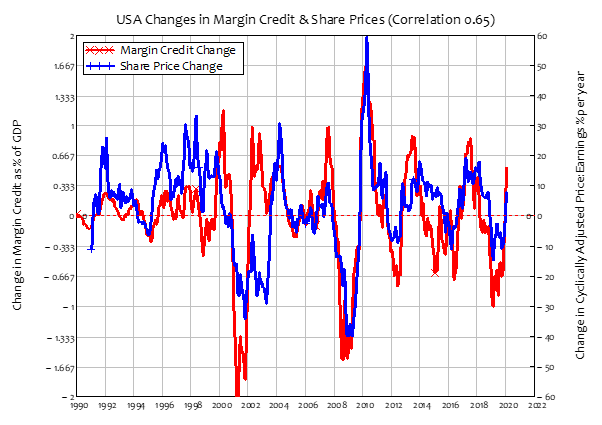

Though the underlying factor in the stock market boom since 2009 has been Quantitative Easing, changes in margin debt have driven the ups and downs of the market—see Figure 5.

Figure 5: USA Margin Credit and Share Prices

Our post-Global-Financial-Crisis world is thus characterized by excessive private sector debt and a moribund private sector, with economic performance kept afloat predominantly by government schemes (like Quantitative Easing) and large budget deficits that in turn lead to high levels of government debt. To escape from this impasse, we need to reduce private debt relative to GDP—and preferably without also further increasing the government debt to GDP ratio.

Conventional ideas about how to reduce the level of debt compared to GDP boil down to three solutions: to simply pay the debt down, to grow GDP faster than debt, or to “inflate our way out of debt”. However, the empirical record implies that none of these methods will work.

Irving Fisher, who developed the “Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions” pointed out that the “pay it down” route fails because reducing debt directly also destroys money dollar for dollar: just as a new loan increases the money supply, paying debt down reduces it:

A man-to-man debt may be paid without affecting the volume of outstanding currency, for whatever currency is paid by one … is received by the other, and is still outstanding. But when a debt to a commercial bank is paid by check out of a deposit balances that amount of deposit currency simply disappears. (Fisher 1932, p. 15)

The fall in money can cause a greater fall in GDP, thus resulting in a rising debt to GDP ratio from direct repayment of debt—a phenomenon that I call “Fisher’s Paradox“:

the very effort of individuals to lessen their burden of debts increases it, because of the mass effect of the stampede to liquidate in swelling each dollar owed. Then we have the great paradox which, I submit, is the chief secret of most, if not all, great depressions: The more the debtors pay, the more they owe. (Fisher 1933, p. 334)

Philanthropist and ex-banker Richard Vague reports in his recent book A Brief History of Doom (Vague 2019) that growing out of debt only worked for economies experiencing sudden, huge export booms, while inflation has never reduced debt significantly.

The only way that debt was reduced, he found, was by writing it off: debt cancellations of one form or another were the only way that countries had reduced their debt burdens substantially.

A debt-cancellation obviously benefits debtors, but it could force creditors—specifically, banks—into bankruptcy. It also rewards those who borrowed to speculate on rising house and share prices, but does nothing for those who weren’t party to the gambling. We need a way to reduce debt relative to GDP, without tanking the economy, without creating moral hazard by letting debtors off the hook while bankrupting creditors, and without rewarding those who rode the debt bubble over those who didn’t, wouldn’t, or couldn’t speculate with borrowed money. And, preferably, without causing a Great Depression and a World War, events that accompanied the last major reduction in debt levels between 1932 and 1953—see Figure 1 and Figure 11.

A “Modern Debt Jubilee” could achieve this. A Modern Debt Jubilee uses the capacity of the government to create money to reduce private debt by effectively swapping credit-backed money for fiat-backed money:

- Rather than debtors having their debt reduced, everyone—borrower or saver—is given the same amount of government-created money;

- Debtors must reduce their debt; savers get cash that must be used to buy newly-issued corporate shares;

- The proceeds from selling these shares must be used to pay down corporate debt; and

- The Jubilee gives banks the finances needed to buy Jubilee Bonds, the interest income from which compensates them for the fall in their income from private debt.

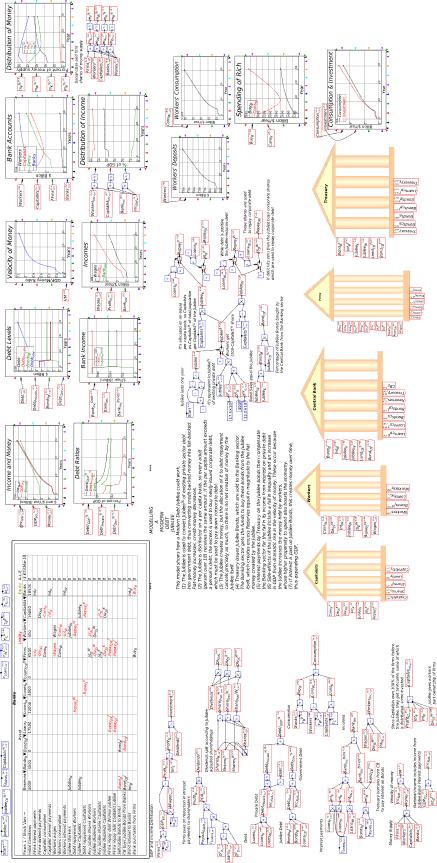

This paper models a Modern Debt Jubilee using Minsky, an Open Source (i.e., free) system dynamics program. Minsky’s unique feature, called a “Godley Table”, is a double-entry bookkeeping table that makes it much easier to model financial dynamics than it is in standard system dynamics programs.

The key outcomes of the model are:

-

The Jubilee reduces overall debt levels, relative to GDP;

- The private debt to GDP ratio falls immediately because of the Jubilee;

- Government debt rises as much as private debt falls, but the government debt to GDP ratio rises less because of the stimulatory effects of the Jubilee on GDP;

- The total debt to GDP ratio therefore falls immediately as a result of the Jubilee; and

- Over time, the Jubilee stimulates the economy because the fall in indebtedness boosts aggregate demand, by transferring money from those who spend slowly (primarily bankers) to those who spend quickly (workers).

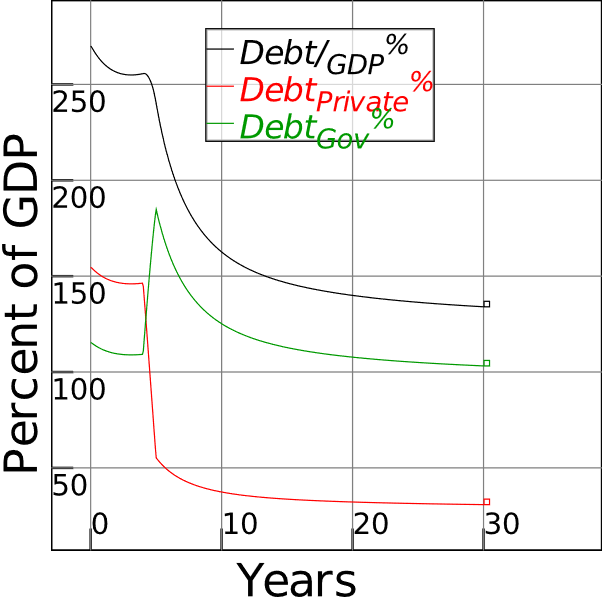

A policy which requires an initial increase in government debt—as fiat-created money replaces credit-based money—thus ends up reducing both government and private debt relative to GDP—see Figure 6.

Figure 6: A Modern Debt Jubilee reduces both private and government debt ratios

How does this magic happen? The basic mechanism is that the Modern Debt Jubilee (MDJ) reduces the inequality that rising level of private debt have caused.

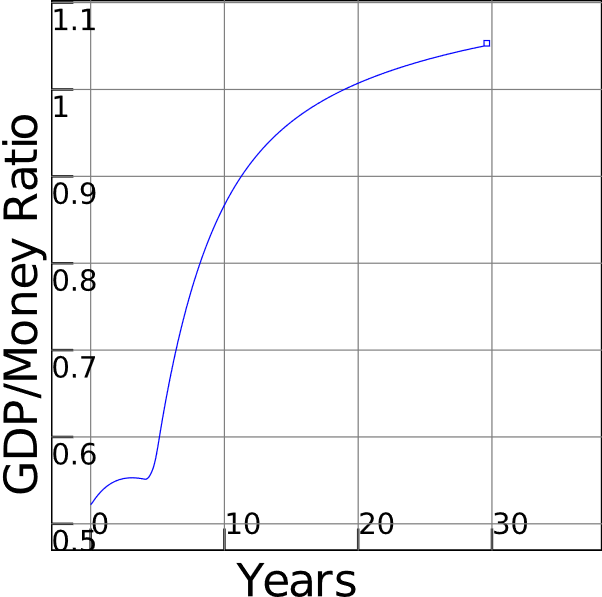

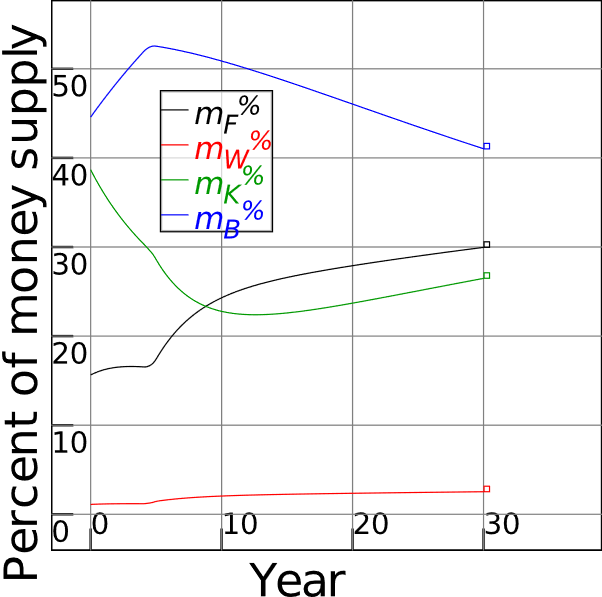

A higher level of private debt, even with falling interest rates, results in a larger fraction of the economy’s money residing in the financial sector rather than the real economy—the shops and factories where physical output are produced, and profits and wages are actually generated. The Modern Debt Jubilee reverses this: by reducing private debt levels, less debt-servicing is needed, and therefore more of the existing amount of money turns up in the hands of workers, who spend much more rapidly than do bankers. Because they spend more rapidly, that money expands activity in the firm sector, causing GDP to rise. The increase in what mainstream economists call the “velocity of money” (see Figure 7) generates more GDP from the same amount of money, and debt to GDP ratios fall over time.

Figure 7: Rising velocity of money because of the Jubilee

A Modern Debt Jubilee thus reverses Fisher’s Paradox. Private debt is reduced, but the stock of money remains constant, and as a bonus, it ends up in the hands of people who spend more rapidly. So private debt falls, and GDP rises as a result, reducing the private debt to GDP ratio even further. The increase in economic activity is so great that, over time, even the government debt to GDP ratio falls as a result of the Jubilee.

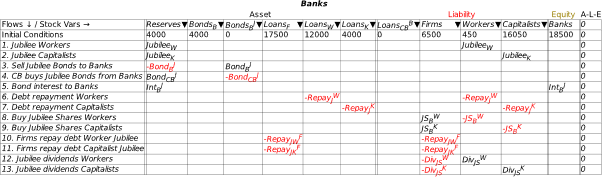

To those who ask, “Who’s going to pay for it?”, a lesson in accounting is in order. Figure 8 shows the basic operations of the MDJ, with the financing operations in the top five rows.

Firstly, the Treasury makes a per capita payment to every adult in the economy. Since most people are employees (“Workers”) rather than employers (“Capitalists”), the vast preponderance—say 95%—of the money goes to workers, with the rest going to capitalists: that’s shown in the first two rows of Figure 8. Note that this operation, like all actions in double-entry bookkeeping, has two components: the bank accounts of both workers and capitalists are credited; and simultaneously the Reserve accounts of the private banks at the Central Bank are credited. The Assets (Reserves) of the private banks rise precisely as much as their Liabilities (Deposits) rise.

Figure 8: The basic operations in a Modern Debt Jubilee

The increase in Reserves enables the next step on the 3rd row: the sale of Jubilee Bonds by Treasury to the private banks. The Jubilee has increased the Reserves of the banking sector; the sale of Jubilee Bonds lets the banks swap this non-income-earning, non-tradeable asset for Jubilee Bonds, which can be traded and can earn interest, just like standard Government Bonds.

This is the key truth to “Modern Monetary Theory”: because the government is a money creator, government spending is self-financing. Financing, in other words, is not the problem: problems, if any, lie with the consequences of that spending, rather than its financing.

Here we have not spending but a “gift” to the private, non-bank public: the government gives the public money which must be used to pay down private debt (rows 6 and 7 in Figure 8). To do so, it also gifts the banking sector with additional reserves—an asset that earns no income. The sale of new government bonds (“Jubilee Bonds”) to the banking sector is another gift, in that it enables the banking sector to swap a non-income-earning, non-tradeable asset for an income-earning, tradeable asset. Of course the banking sector will accept this gift—which is why every government bond issue in history has been oversubscribed. There are no “Bond Vigilantes”, only “Bond Idiots” who would turn down not one gift but two.

How much this second gift costs—in terms of the interest payments made on the bonds—depends on how much of the bond issue remains with private banks. It is quite possible for the Central Bank to buy all of the Jubilee Bonds from the private banks if it wishes (row 4 of Figure 8): all it has to do is credit their Reserve balances (the Central Bank’s Liability to private banks) and put the bonds on its balance sheet as an Asset of equivalent value. This would then mean that the Jubilee would cost the government nothing, because it would be financed by one part of the Government (the Treasury) going into debt with another part (the Central Bank).

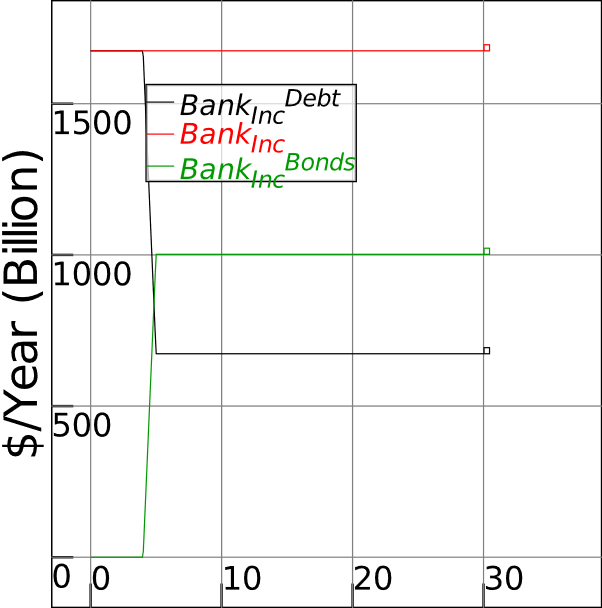

But the biggest objectors to that happening would probably be the private banks themselves, because the reduction in private debt—by roughly 100% of GDP in the simulations here—would reduce their income dramatically. Here, row 5 of Figure 8 comes into play: the Treasury paying interest on the bonds to the banks. This is the “cost” of the Jubilee: it’s the amount of interest needed to keep the banking sector happy, after it loses a large source of income from the repayment of private debt. It is quite possible for interest rate on Jubilee Bonds to be set at a level which fully compensates the banking sector for the loss of income from interest on private debt, as illustrated by Figure 9.

Figure 9: Bank income when Jubilee Bonds pay the same rate as interest on private debt

The interest itself can be raised by Treasury borrowing from the Central Bank—so if the Jubilee were of the order of 100% of GDP, as in these simulations, the annual “cost” of this would be an increase in the Treasury’s debt to the Central Bank of 5% of GDP, or $1 trillion per year.

There is also a social bonus to paying interest on the Jubilee Bonds: as well as compensating the banks for lost income on private debt, it also creates money: it increases the Reserves (Assets) of the banking sector and its Equity at the same time. So the “cost” of the Jubilee would be a $1 trillion injection of new money into the banking sector every year.

A Modern Debt Jubilee would thus overcome the problem of an excessive ratio of debt to GDP by affecting the denominator—GDP—more than the numerator—debt, both public and private. It main effects occur because of its effects on the money supply—both who has it, and how it grows. This reallocation of existing money—see Figure 10—reverses the historic mistake Central Banks have made via Quantitative Easing, which was undertaken ostensibly to stimulate the economy, and did by making the wealthy wealthier, via higher share prices.

Figure 10: Distribution of money under a Jubilee. more money for Firms, Workers and Capitalists and less for Banks

The model still abstracts from much of the detail of the real world, but it is realistic about money creation, in stark contrast to mainstream Neoclassical economic models, which ignore money creation completely. It implies that there is a way out of our current impasse, and the main impediment to it happening is the ignorance about money creation that mainstream economics itself has caused.

More policies would be needed to support a Jubilee: you wouldn’t want to reduce the private debt burden, and then have banks recreate it via the irresponsible lending practices they have followed in the last 40 years. This would include curbs on bank lending for asset purchases, and encouragement to banks to lend to firms and entrepreneurs, rather than to speculators, as they have been predominantly doing since the 1970s.

Government policy after the Jubilee should be expanded from targeting only unemployment and inflation to include targeting private debt as well. It needs to be kept at sustainable levels—of the order of the 50% of GDP that it was in capitalism’s Golden Age after WWII.

It’s possible to see this last time we escaped from a private debt trap—the 1930s and 1940s—as a crude version of what I’m proposing here. Increased government spending, firstly for the New Deal and then for World War II, enabled the private sector to drastically reduce its debt level—see Figure 11.

Figure 11: How we escaped from the last private debt bubble

We just need to avoid the mistakes made back then, of reducing private sector debt by a War rather than a Jubilee, and of allowing the private banking genie to get out of the bottle again afterwards. A well-functioning economy needs a balance of fiat and credit money, and once this is restored by a Modern Debt Jubilee, it needs to be maintained by a government that is well aware of the dangers of surrendering control over the money supply to those whom Marx so aptly characterized as “the Roving Cavaliers of Credit” (Marx 1894, Chapter 33).

Figure 12: The full Minsky model of a Modern Debt Jubilee

References

Bernanke BS (2000) Essays on the Great Depression. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Fisher I (1932) Booms and Depressions: Some First Principles. Adelphi, New York

Fisher I (1933) The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions. Econometrica 1 (4):337-357

Keen S (2020) Emergent Macroeconomics: Deriving Minsky’s Financial Instability Hypothesis Directly from Macroeconomic Definitions. Review of Political Economy 32 (3):342-370. doi:10.1080/09538259.2020.1810887

Kelton S (2020) The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and the Birth of the People’s Economy. PublicAffairs, New York

Mankiw NG (2016) Macroeconomics. 9th edition edn. Macmillan, New York

Marx K (1894) Capital Volume III. International Publishers, Moscow

McLeay M, Radia A, Thomas R (2014) Money creation in the modern economy. Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin 2014 Q1:14-27

Vague R (2019) A Brief History of Doom: Two Hundred Years of Financial Crises. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia