Over the last few days, a mystery in which I have a cameo role has been solved on Twitter: “which famous wit made the observation that white Anglo-Saxon Australians, as well as being descended from convicts, were also descended from warders—Clive James or Peter Ustinov?”

Matthew eventually concluded—correctly—that it was Peter Ustinov. I know he was correct, because Ustinov first used that line on me, on September 11 1978.

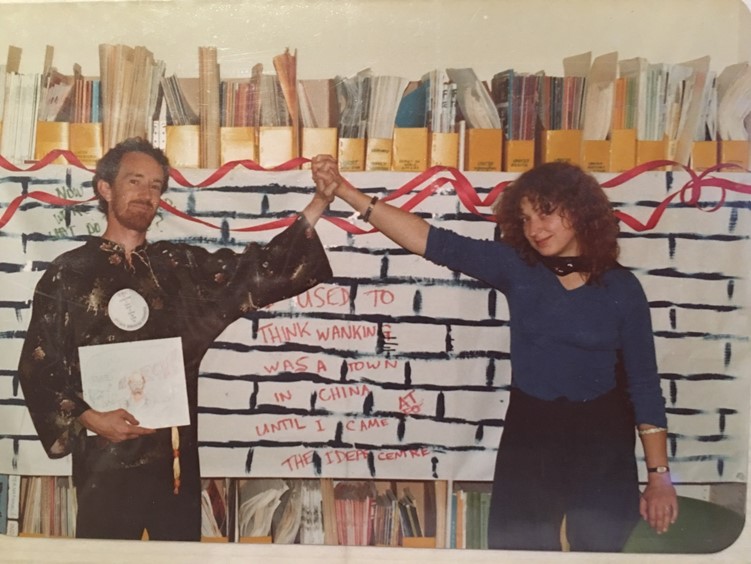

At the time, I was Education Officer for the Australian Freedom From Hunger Campaign (FFHC), and worked in its innovative library The Ideas Centre, which was housed in a since-demolished 4-storey building on the corner of Clarence and Margaret Streets, on the periphery of Sydney’s Central Business District.

Ustinov had been a famous actor—and tasted fame once more very shortly afterwards, as Hercule Poirot in Agatha Christie’s Death on the Nile and several subsequent movies.

But at the time, he was best-known as the Goodwill Ambassador for UNICEF, the United Nations Children’s Fund. For some reason, FFHC’s then public relations manager Mary Leggett thought that it would be a good idea to bring Ustinov out to Australia to promote Freedom from Hunger. I thought it was a silly idea: at the time Ustinov was Mr UNICEF, and we’d effectively be giving UNICEF some free publicity. But my misgivings were ignored, and the tour went ahead.

Inexplicably, no plans were made to greet Ustinov at the airport, and he was left to get a taxi to my office, before flying to Canberra the next day. So, as a 25-year-old, I rehearsed several greetings for the most famous person I’d ever met—none of which I got to use. Instead, my first words were

“What on Earth happened???”

Ustinov, who was a bear of a man, had simply collapsed into the chair next to my desk, in obvious distress. “I’ve just had the worst taxi drive of my life!”, he exclaimed.

This was in the days when the main road linking Sydney’s CBD to its airport was O’Riordan Street, a narrow, twisting 4 lane road running through an industrial area, with 2 of its lanes full of parked cars and its bitumen cracked by countless heavy vehicles. I had visions of Ustinov sitting fearfully on the back seat as a kamikaze driver ran intersections and overtook trucks.

But that wasn’t it at all, as Ustinov explained:

As soon as I sat in the cab, the driver took one look at me in the rear vision mirror, saw that I was white, thought that since I was white I’d have the same opinions as him, and launched into the most vile racist diatribe I’ve ever heard. He said how he had flats in the suburbs that he rented out to “Wogs”, and how he’d happily smash their TV sets when he came to collect the rent, and otherwise terrorise them.

Then he took another look in the rear vision mirror, and saw that I was appalled. His whole demeanour changed, and he suddenly snarled:

(Ustinov put on a rough Australian drawl and said) “I suppose you don’t give a fuck what I think. I suppose you think all us Australians are descended from fucking convicts!”

“What did you say?”, I asked. Ustinov replied:

I said “On the contrary, my dear man, I’m convinced you’re descended from one of the warders”.

Magnificent, I thought! What a brilliant way to summarise the weird schism in the Australian psyche, between the larrikin willing to give authority the finger, and the authority figure imposing order upon the rabble.

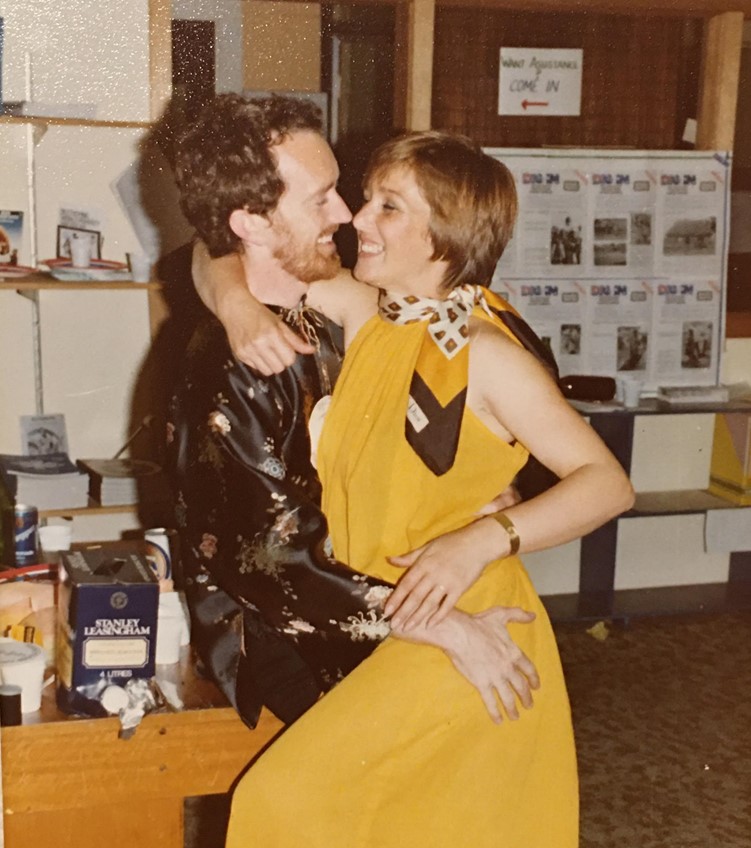

I first recounted this story in 2011, in disgust at the police shutting down the Occupy Sydney protest: “Australia: beautiful one day, police state the next“. What I didn’t add then is that, a couple of years later, I got a taxi ride from the same racist driver, en route to my resignation party from Freedom From Hunger.

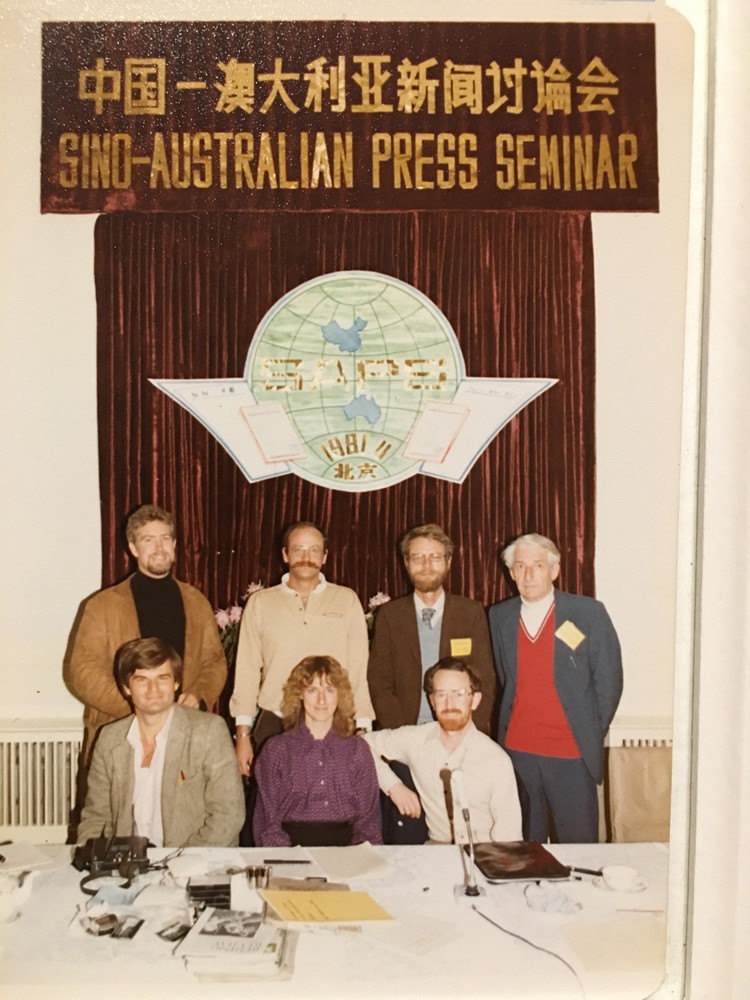

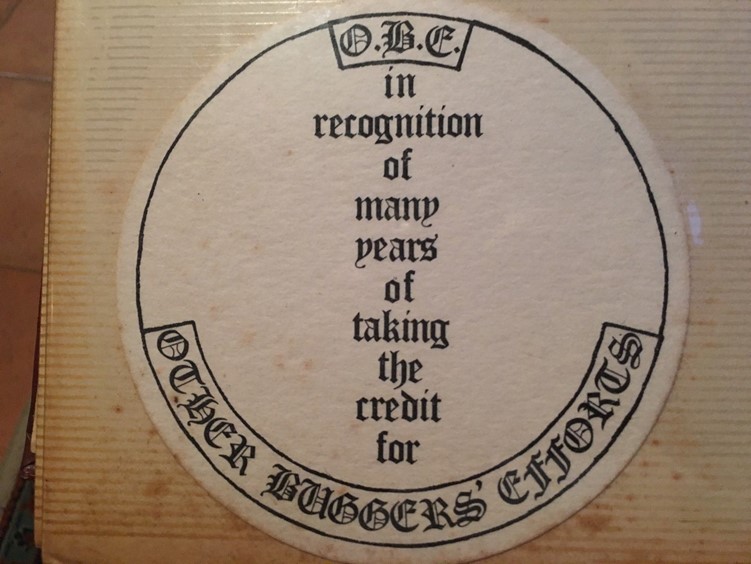

Though I loved the work and the community of overseas aid activists I worked with, I was sick of our initiatives being blocked by the useless SOBs (“Sons—and daughters—of the Bourgeoisie”) who chaired the governing committees of organisations like Freedom From Hunger. Bill Hobbin, FFHC’s President at the time, satirised them as OBEs: people who take the credit for “Other Buggers’ Efforts”. They had turned down one too many of my proposals—this time, to run a seminar between Australian and Chinese journalists on the coverage of each country in the other’s press—so I resigned to do it myself.

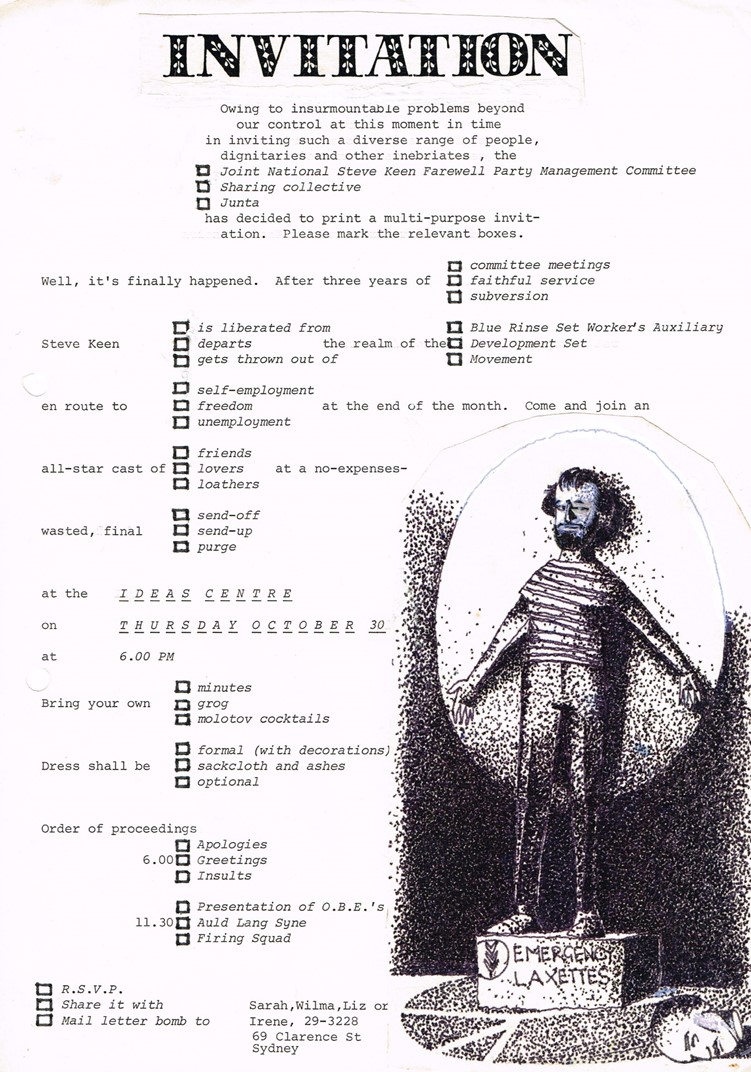

I decided to leave Freedom from Hunger with a bang rather than a whimper. I sent out an invite that parodied the tribes that inhabited overseas aid organisations—the libertarian leftists, the do-gooders hanging out for a knighthood, the bureaucrats and the revolutionaries:

I produced suitable drink coasters:

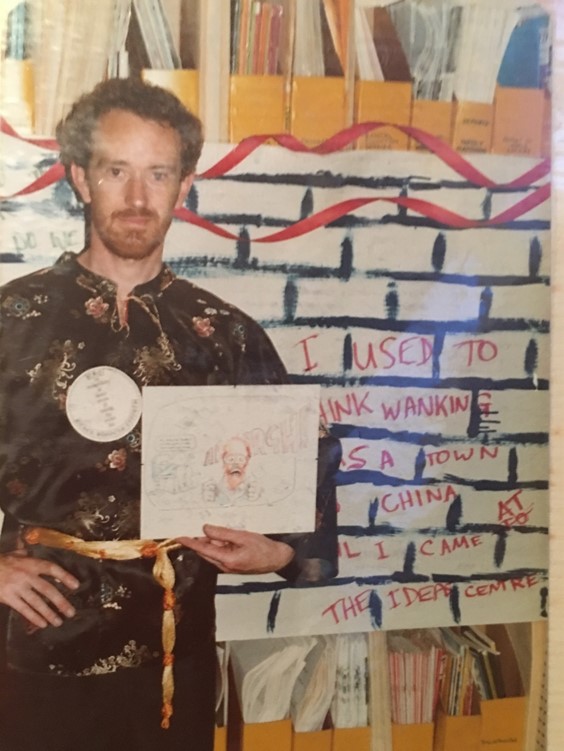

And I wore a provocative take on the “black silk pyjamas” of the Vietcong:

There was no way that I was going to take public transport wearing that getup, so I called a taxi.

Because I was wearing this gear, I sat in the back seat—back then (and still to some extent today), the Australian custom was to sit in the passenger seat next to the driver, but I wasn’t going to freak my driver out by plonking down next to him wearing this gear.

And the driver took one look at me in the rear vision mirror, saw that I was white, thought that since I was white I’d have the same opinions as him, and launched into the most vile racist diatribe I’ve ever heard.

It was not merely word perfect for what Ustinov had recounted two years earlier, it was pitch perfect as well. Ustinov was a brilliant linguist and mimic, and he had captured this arsehole’s voice brilliantly. So I listened as he told me how he had flats out west that he rented out to “Wogs” (and “Chinks”), how he’d bust their TV sets up when he went to collect the rent… The whole damn thing.

Unlike Ustinov, I managed to keep a straight face—probably partly in shock that this was happening at all, let alone on the day that I was leaving this caring career for good.

When he deposited me at 69 Clarence Street, I said “Thank you, for reminding me why I did the work I’ve done for the last three years”, and went in to party with the good people who were the polar opposite of this despicable descendant of a warder.

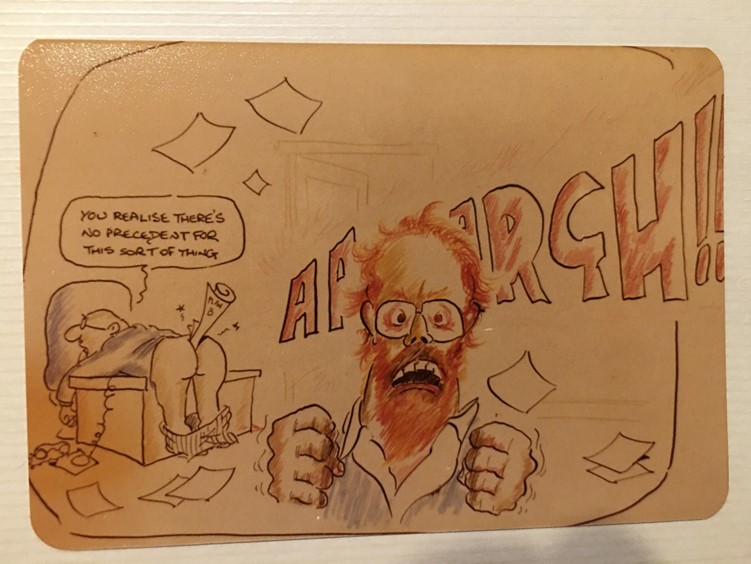

My partner in crime at the Ideas Centre, Sarah Sargent, arranged a priceless farewell present for me: a Patrick Cook cartoon:

So raise a glass to toast Peter Ustinov, one of the wittiest, nicest, and wisest humans ever.