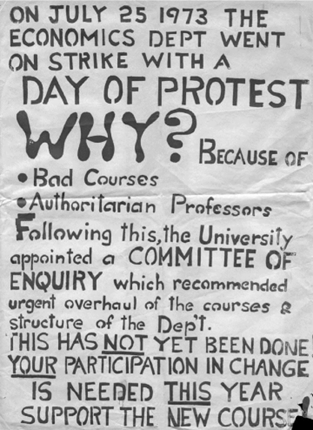

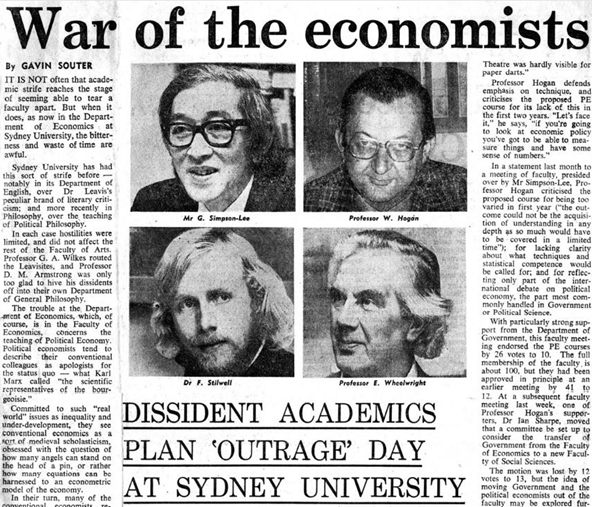

Pardon two nostalgia posts in a row, but after writing The Day I Pranked Paul Samuelson, I realised that I’d let pass possibly the most important anniversary in my peripatetic life: the 50th anniversary of “The Day of Protest” at Sydney University on July 25th 1973.

It was, to my knowledge, the first ever protest over economic theory and how it was taught at a university. Nothing like it happened again for almost 30 years, when French students created the Protest Against Autistic Economics (PAECON) in September 2000.

Another dozen years passed before students at Manchester University formed the Post-Crash Economics Society to revolt against their Neoclassical curriculum in the aftermath to the Global Financial Crisis.

All three protests had the same motivation. To quote from the first issue of the Post-Autistic Economics Newsletter, the French protesters called for “an end to the hegemony of neoclassical theory and approaches derived from it, in favour of a pluralism that will include other approaches, especially those which permit the consideration of “concrete realities”.”

Each of these protests was successful in the short-term. Our protest at Sydney University led to the formation of a Department of Political Economy; the French students’ protest gave birth to the Real-World Economics Review, which is still going today; and the Manchester protests led to the formation of Rethinking Economics, which supports students around the world who are dissatisfied with the state of economics today.

But more than 50 years after our protest, that same hegemony is alive and well—or at least undead. The Neoclassical pedagogy that I railed against in the 1970s has evolved into something even more absurd and anti-realistic than the absurd and anti-realistic dogmas I protested against in 1973 (Krueger 1991). So, since the objective of our protests was to replace the fantasies of Neoclassical economics with a realistic approach to economics, they have failed.

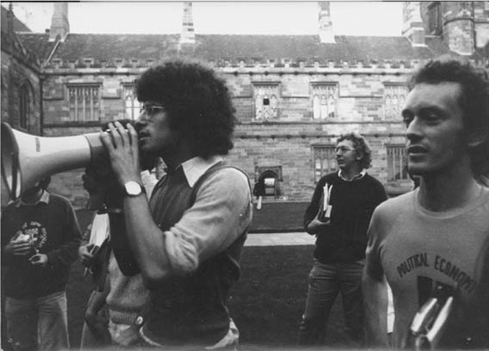

Of course, we didn’t know that we would fail, back in July 1973, when 300+ students voted to hold a “Day of Protest” against the boring and delusional theories we were being fed by the conservative curriculum at Sydney University. Instead, we experienced the thrill of openly challenging our Professors, giving alternative lectures on the actual day, marching, chanting, waving banners, partying, and, in subsequent years, occasionally occupying the Vice-Chancellor’s office.

It was an exciting and life-changing experience for us all—for me more than most, since I devoted the rest of my life to continuing the rebellion we started in 1973. The buzz of optimistic rebellion is hard to explain to today’s harassed students, flitting between one part-time job and another as they try to pay their student debts. In 1973, it felt like real change was possible.

What do we want?

Political Economy!

When do we want it?

Now!

But what have we got, 50 years later? Political economy has continued on, but the mainstream is as ascendant as ever—despite its numerous failings at the time and since.

I had hoped, in those subsequent years, that a clear failure by Neoclassical economics would help expose it for the fraud it is: the failure to realise, in the Noughties, that a serious economic crisis was imminent (Keen 2006, 1995, 2020). Not only did they not realise it, they actually thought that they had eliminated the very possibility of crises. Speaking as the incoming President of the American Economic Association, Robert Lucas—one of the fountainheads of modern Neoclassical macroeconomics—made the following bold and utterly false statement in his Presidential lecture at the end of 2002:

Macroeconomics was born as a distinct field in the 1940’s, as a part, of the intellectual response to the Great Depression. The term then referred to the body of knowledge and expertise that we hoped would prevent the recurrence of that economic disaster. My thesis in this lecture is that macroeconomics in this original sense has succeeded: Its central problem of depression prevention has been solved, for all practical purposes, and has in fact been solved for many decades. (Lucas 2003, p. 1. Emphasis added)

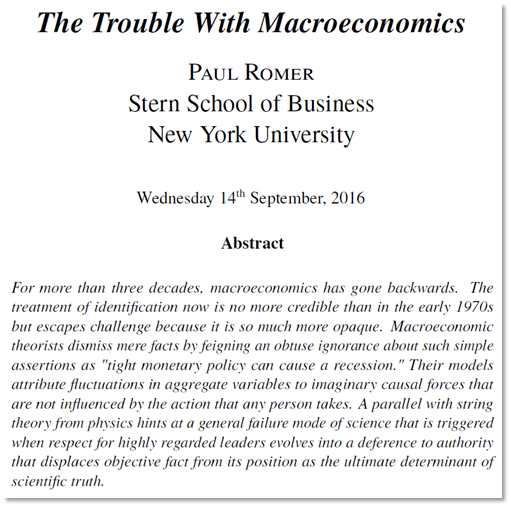

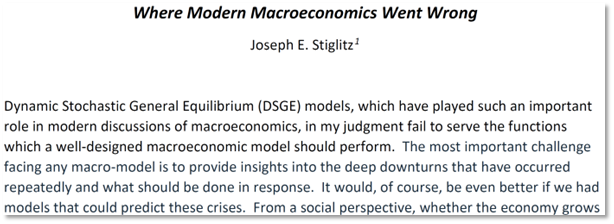

Two decades later, despite the failure of Neoclassical “Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium” models to anticipate the biggest economic crisis since the Great Depression, and despite Nobel Laureates like Paul Romer and Joseph Stiglitz rubbishing them, they are still the workhorses of Neoclassical economics.

Today’s students are still required to learn these arcane and misleading models, as if the crisis they failed to anticipate did not occur.

Why has Neoclassical economics persisted, despite its many failures? Mainly because, as Max Planck put it, a real science overthrows a false paradigm, not by persuading existing believers to change their minds, but by generational change:

It is one of the most painful experiences of my entire scientific life that I have but seldom—in fact, I might say, never—succeeded in gaining universal recognition for a new result, the truth of which I could demonstrate by a conclusive, albeit only theoretical proof… A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it. (Planck 1949, pp. 22-4. Emphasis added)

Generational change occurs in sciences because, once an anomaly is discovered that contradicts a prediction of the dominant paradigm, the anomaly exists forever, and any student can replicate it for themselves. Once the Michelson-Morely experiment disproved the theory of the “aether“—a substance that, according to the Maxwellian theory of electromagnetics, was supposed to fill space to enable light waves to be transmitted through it—then any student could find the anomaly for themselves.

But in economics, anomalies are historical and transient. The Great Depression, WWII, the post-War “Golden Age of Capitalism”, the 70s Stagflation, the 80s stock market bubble, the 90s recession, the Great Recession, now the post(?)-Covid boom and inflation… Each new crisis knocked the previous one off its pedestal. The fact that Neoclassical economics can’t explain the Great Depression—or that it has an explanation which is an insult to anyone who lived through it (Prescott 1999)—doesn’t matter to any modern economist who is working on the Covid inflation issue. Old failures can be forgotten.

Just as importantly, the underlying Neoclassical vision of capitalism is a highly seductive one: it is a meritocracy in which what you earn is what you deserve, where harmony rules because of equilibrium, and which is free of coercion: there’s no need for government control when the market works perfectly. Therefore, even if some students break away from Neoclassical economics because of one of its failures, enough “true believers” can be found in the student body to replace existing “true believers” when they retire. I spent my late teens fighting against believers in Neoclassical economics who were then two to three times my age. Now in my seventies, I am fighting believers in Neoclassical economics who range from being my contemporaries (Paul Krugman is one month older than me) to being one third of my age.

In a nutshell, funerals aren’t enough for a true scientific revolution in economics.

The final factor that enables economics to escape the revolutionary change it desperately needs is rather ironic: myths in economics survive because, despite the dominance of our politics by economic ideas, you don’t need economic theory or economists to have an economy. The economy exists independently of economists, and would probably function a lot better if economists simply didn’t exist. In contrast, engineering doesn’t exist independently of engineers: you need engineers to create the technological marvels the rest of us take for granted, and when something goes wrong with the things that engineers create, engineers face real consequences: a collapsing bridge fingers the engineers who didn’t take account of its harmonics, a crashing plane implicates the engineers (or their managers) who approved a faulty design.

To use Nicholas Taleb’s phrase, economists don’t have any “skin in the game”: they don’t suffer any serious consequences when their advice is badly wrong, and there is a myriad of complicating factors that they can point at to explain away any failure. Ironically, the fact that economists aren’t strictly necessary is something that gives them great power—they are the witchdoctors of capitalism, holding the leaders of our society in their thrall, while at the same time having no idea how that society actually works.

So, do I regret organizing The Day of Protest, half a century ago? Not a bit of it.

Firstly, though our protest failed to dislodge the mainstream, we were as right about Neoclassical economics being a false paradigm as Galileo was about the Ptolemaic model of the universe—and these days I’ve taken to referring to Neoclassical economics as Ptolemaic Economics to highlight that point. One should never regret fighting for truth and against fallacy.

Secondly, it was rewarding hard work. The 50 or so of us who put The Day of Protest together had never worked so hard in our lives before, and possibly since, and we worked for passion and a commitment to truth, rather than for money. Richard Osborne first proposed the idea, and became a pivotal part of our negotiating team; Greg Crough, Graham Kerridge, Richard Fields and I initiated the revolt and gave several of the alternative lectures; Bill Nichols responded to the need for banners by producing two 25 metre-long calico banners and numerous smaller ones; Kevin McAndrew churned out posters like an automaton.

Thirdly, I saw real courage at work. Several of the staff openly sided with the students: Paul Roberts, Jock Collins, and above all Frank Stilwell, put their careers on the line by speaking out in our favor, literally in full view of the Professors. Margaret Powers and Geelum Simson-Lee assisted us within the confines of the University’s administrative system. Other departments—including Accounting and Politics (then called Government) surreptitiously assisted us with printing facilities, and voted with us in the eventual successful Faculty motion to investigate the Department of Economics.

Fourthly, it was great, great fun. Hundreds of students attended the alternative lectures we put on, and most stayed for the mother of all parties that finished the evening.

Finally, it pointed the right way when the world was about to embark on a journey in the opposite direction. We didn’t realise it then, but our rebellion in 1973 was the counterpoint to the ascendancy of Neoclassical economics in the world of policy: at the same time that we were trying to pull it down, politicians, administrators and journalists around the world were succumbing to its fantasies. The stagnant and crisis-ridden decades that followed showed the gap between its promises and the impact of imposing its false beliefs on the real world.

If I had done nothing else of significance in the following 50 years, I could still look back on The Day of Protest with great pride and pleasure. So, from my 70-year-old self in 2023, to the 20-year old rebel in 1973, here’s lookin’ at you, kid.

Keen, Steve. 1995. ‘Finance and Economic Breakdown: Modeling Minsky’s ‘Financial Instability Hypothesis.”, Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 17: 607-35.

———. 2006. “Steve Keen’s Monthly Debt Report November 2006 “The Recession We Can’t Avoid?”.” In Steve Keen’s Debtwatch, 21. Sydney.

———. 2020. ‘Emergent Macroeconomics: Deriving Minsky’s Financial Instability Hypothesis Directly from Macroeconomic Definitions’, Review of Political Economy, 32: 342-70.

Krueger, Anne O. 1991. ‘Report of the Commission on Graduate Education in Economics’, Journal of Economic Literature, 29: 1035-53.

Lucas, Robert E., Jr. 2003. ‘Macroeconomic Priorities’, American Economic Review, 93: 1-14.

Planck, Max. 1949. Scientific Autobiography and Other Papers (Philosophical Library; Williams & Norgate: London).

Prescott, Edward C. 1999. ‘Some Observations on the Great Depression’, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review, 23: 25-31.