One of my recurring fantasies is to reanimate Maggie Thatcher and Ronald Reagan on UK and Dutch trains, to tell them the year, and then ask them where they think they are—with only the ownership information and the performance and quality of the carriages to go on. The UK has privatised its rail system, the Netherlands’ system is still in public ownership; one has high quality modern fast trains, while the other is still operating museum pieces.

In researching this post, I’ve realised that I’m being a bit harsh on Thatcher—it was her successor John Majors who privatised the UK’s railways, and Thatcher herself was apprehensive about how privatisation would actually perform (McCartney and Stittle 2017, p. 2). But apart from that, I’d bet bottom dollar that they would get their locations 100% wrong. When sitting in the modern, high-speed trains, they’d think they were in the UK; and when sitting in the museum pieces slowly vibrating their way forward, they’d think they were in The Netherlands.

As someone who spends a lot of time on both rail systems, I know that the opposite is starkly true. British rail services are antiquated, unreliable, expensive, and slow. Dutch—and most European publicly owned and operated rail services—are modern, reliable, cheap and fast.

So, why did it all go do wrong, Maggie and Ronnie?

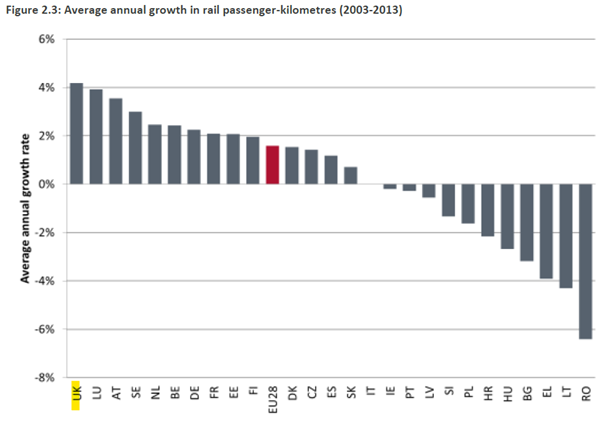

The numbers—charts here come from an EU survey (Steer-Davies-Gleave 2016)—are stark. Passenger miles, remarkably, have grown more in the UK than anywhere else in Europe (see Figure 1), so there’s reason to expect the UK might have benefited from economies of scale in this high-fixed-cost industry. If so, fares should have grown more slowly in the UK than elsewhere—and this is what (McCartney and Stittle 2017) predict would have happened, had the UK’s system not been privatised.

Figure 1: (Steer-Davies-Gleave 2016, p. 6 )

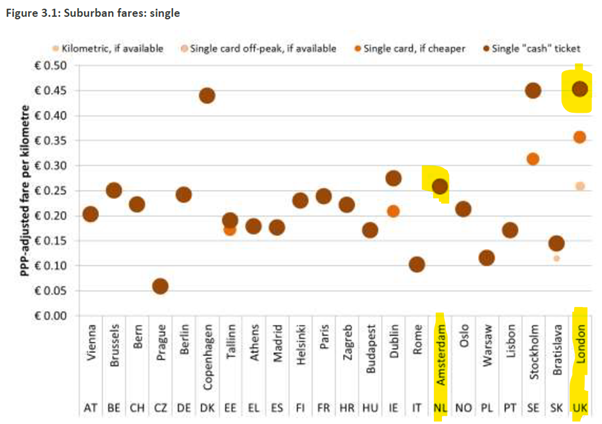

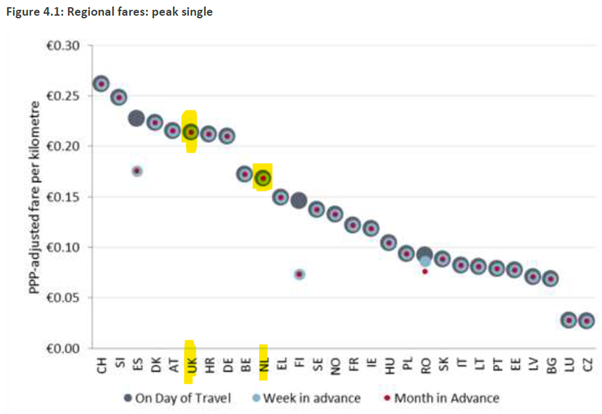

But the privatised system has resulted in much higher costs for UK commuters than their European counterparts, at every distance from suburban (see Figure 2) to interurban (see Figure 3, Figure 4, and Figure 5).

Figure 2: (Steer-Davies-Gleave 2016, p. 37) The list is alphabetical, and the UK tops the costs for suburban fares

Figure 3:(Steer-Davies-Gleave 2016, p. 56)

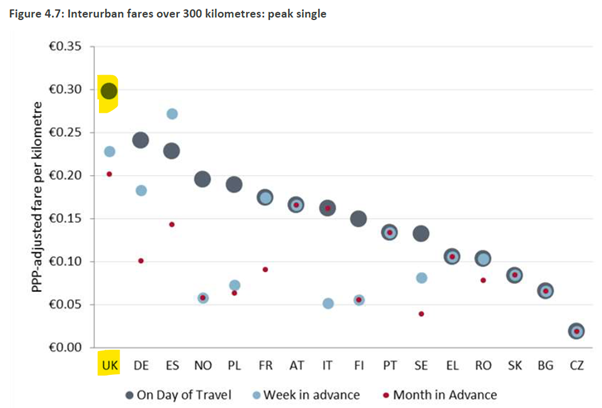

The outcome is worst at the interurban level, where UK trains are two to six times as expensive as their European counterparts—see Figure 4.

Figure 4: (Steer-Davies-Gleave 2016, p. 60)

The practical import of this is to make the UK into a set of isolated city economies, with only one of those—London—being of any significant scale. A rail journey of any distance in the UK is a prohibitively slow and expensive undertaking, so private sector economic activity remains small scale (or roads take the burden, but at higher monetary, environmental and time costs). The poor quality and high cost of the UK’s rail system has led to a fragmented and underperforming private sector as well.

Figure 5: (Steer-Davies-Gleave 2016, p. 63) The Netherlands isn’t listed because it’s too small for +300km interurban routes

McCartney and Stittle conclude that “in cost terms alone, the dismantling of British Rail was ill-judged and has proved to be a major public policy error… proponents of privatisation argued that the private sector would improve efficiency and provide ‘better value for money’ over the ‘dead hand’ of the state. But this was largely an illusion… (McCartney and Stittle 2017, pp. 16-17).

Why did privatisation fail, on its own grounds? McCartney and Stittle give a good analysis of this in terms of the conditions of the rail industry alone, but I’m thinking of the wider issue: is there a general issue behind the failure of privatisation to deliver what its proponents expected in so many areas, from rail to education to sewerage management?

The Payback Period

Avner Offer provides such a general principle in his recent book Understanding the Private-Public Divide: Markets, Governments and Time Horizons (Offer 2022): the time horizon for investment in ventures like railways, schools and sewerage systems lies outside the payback period that private investors expect:

in market societies, undertakings that pay off inside the credit time horizon are typically undertaken by business. This suggests a division of labour: market competition for short-term provision; government, not-for-profits, and the family for long or uncertain durations. This boundary predicts where the limit is likely to run and sets down where it ought to be. When violated in either direction, poor outcomes are likely, inefficiency, corruption, or failure. (Offer 2022, p. 13)

The current UK catastrophe with sewerage-laden rivers provides a particularly stark example of this: it is, as one TV commentator remarked, “immensely profitable” not to invest in the infrastructure that would stop raw sewerage being dumped into UK rivers. The returns from the investment are slow and occur over long time horizon; it’s actually more profitable to not make the investment now, and either dump the cost on the community (degraded waterways), or let some future management wear the disaster management costs in the distant future.

Public ownership, on the other hand, leads to public-service-oriented management, and the investment will be made because it’s the right thing to do in public service terms, and not because it creates a higher return today. Paradoxically, this can lead to lower costs and prices to the public from public ownership, because keeping the infrastructure up to date reduces maintenance and other costs indefinitely.

This perspective takes ideology out of the public-private question: businesses with short-term or medium-term returns are the private sector’s forte; services with long-term returns are best handled by the public sector.

I’d go one step further than Offer in defining the payback period—which he relates mainly to the length of time it takes for interest on a loan to equal the original loan itself:

The higher the market interest rate (or the private discount rate), the less time is available to break even… The time boundary between private and public enterprise is easy to draw. It is the ‘payback period’, the time required for interest on a loan to add up to the original advance, under the prevailing interest rate… A project which takes longer than the payback period to break even cannot pay its capital cost and cannot be undertaken for profit. (Offer 2022, pp. 13-14. Emphasis added)

Even at currently elevated interest rates, that implies that the time-division between favouring private and public ownership is 20 years. But the payback period that businesses contemplate is often much shorter than that: Offer notes that “Three different studies suggest rates of return around 15 per cent (payback 6.6 years)” (Offer 2022, p. 15). Also, investment advisors disparage the payback period “because it ignores the time value of money”. However, the mathematician-turned-economist John Blatt provided an ingenious explanation of how the payback period in fact includes not only “the time value of money” but also uncertainty about the future (Blatt 1983, 1980, 1979).

Standard time value of money calculations like Net Present Value discount expected future returns by the prevailing interest rate, plus sometimes an additional margin for uncertainty. Blatt points out that this implies that uncertainty is constant over time, but at the very least, uncertainty about future returns rises with time. So, he proposed discounting by the interest rate plus an additional amount multiplied by time: discount by , rather than just by : the additional factor accounts for the uncertainty of future returns.

This gives a sharply nonlinear profile to the discount, which can be factored into the desired rate of return and the probability of a failure of expected returns to occur. The payback period combines the two, and it is therefore more sophisticated, in terms of accounting for time, than Net Present Value.

It also explains the very short private sector payback period that Offer found rules in practice, of not 20 years but 6-7. Uncertainty about the future is more important than the interest rate.

Privatising the rail system was thus one of many own-goals in UK public policy. The expectations were that this policy would boost the UK’s performance:

When a commitment to privatise the railways was finally made by the Major government (in the Conservatives’ Election Manifesto in 1992) these problems [considered by Thatcher] were simply ignored. The subsequent White Paper, a slim document of 21 pages ‘rather lightweight’ on the economic rationale behind the privatisation plans blandly asserted that a privatised industry would ‘mean more competition, greater efficiency and a wider choice of services more closely tailored to what customers want’ and ‘provide greater opportunities to . . . reduce costs, without sacrificing quality’ (McCartney and Stittle 2017, p. 2).

Not only did the opposite occur, but fallacy led to farce, in that the UK’s poorly functioning private rail sector is largely owned by the EU’s well-functioning public one:

and indeed now, in a farcical twist that nobody could have foreseen, many of the franchises are actually run, not by private enterprise but by state-owned European rail operators—the very ones that British Rail was out-performing in the 1980s. (McCartney and Stittle 2017, p. 17)

Blatt, John M. 1979. ‘Investment Evaluation Under Uncertainty’, Financial Management Association, Summer 1979: 66-81.

———. 1980. ‘The Utility of Being Hanged on the Gallows’, Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 2: 231-39.

———. 1983. Dynamic economic systems: a post-Keynesian approach (Routledge: New York).

McCartney, S., and J. Stittle. 2017. ”A Very Costly Industry’: The cost of Britain’s privatised railway’, Critical perspectives on accounting, 49: 1-17.

Offer, Avner. 2022. Understanding the Private-Public Divide: Markets, Governments and Time Horizons (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge).

Steer-Davies-Gleave. 2016. “Study on the prices and quality of rail passenger services.” In, edited by European Commission Directorate General for Mobility and Transport. European Commission Directorate General for Mobility and Transport.