In contrast to its attitude to private debt, which it ignores, mainstream economics obsesses about government debt. But this volte-face doesn’t besmirch its record of being 100% wrong.

This is the first half of chapter nine of my draft book Rebuilding Economics from the Top Down, which will be published later this year by the Budapest Centre for Long-Term Sustainability

The previous chapter was Why Credit Money Matters, which is published here on Patreon and here on Substack.

If you like my work, please consider becoming a paid subscriber from as little as $10 a year on Patreon, or $5 a month on Substack

Government debt, mainstream economics tells us, is a scourge to be minimized, if it can’t be entirely avoided. These quotes are from Mankiw’s influential macroeconomics textbook {Mankiw, 2016 #6107}, with indicative passages highlighted:

When a government spends more than it collects in taxes, it has a budget deficit, which it finances by borrowing from the private sector or from foreign governments. The accumulation of past borrowing is the government debt… (555)

The government debt expressed as a percentage of GDP roughly doubled from 25 percent in 1980 to 47 percent in 1995. The United States had never before experienced such a large increase in government debt during a period of peace and prosperity. Many economists have criticized this increase in government debt as imposing an unjustifiable burden on future generations… (557)

These trends led to a significant event in August 2011: Standard & Poor‘s, a major private agency that evaluates the safety of bonds, reduced its credit rating on U.S. government debt to one notch below the top AAA grade. For many years, U.S. government debt was considered the safest around. That is, buyers of these bonds could be completely confident that they would be repaid in full when the bond matured. Standard & Poor’s, however, was sufficiently concerned about recent fiscal policy that it raised the possibility that the U.S. government might someday default. (559)

Increases in government debt are a concern because they place a burden on future generations of taxpayers and call into question the government’s own solvency. (595)

This attitude towards government debt and deficits—that government debt should be minimised, that deficits are undesirable, that interest payments on government debt are a punitive impost on future generations, and that high debt and high interest payments can even lead to a government going bankrupt—are key facets of contemporary politics. They were behind the attempt by the UK Cameron government to run surpluses rather than deficits, on the principle that, by “saving for a rainy day”, the government would have more money on hand when crises struck in the future. They lie behind the recurring “debt ceiling” debates in the US Congress. They are the basis of the Eurozone rules, enshrined in the Maastricht Treaty, that government debt should not exceed 60% of GDP, and deficits should be no more than 3% of GDP.

And they are all completely wrong, as is easily shown by looking at the accounting of the mixed credit-fiat monetary system in which we live. I will explain this very, very slowly. It may be tedious to read—it was tedious to write!—but this is necessary, given that utterly fallacious beliefs about the financial system are ingrained into, and damage, our political and social systems, thanks to erroneous mainstream economic thinking.

-

The Fundamentals of Fiat Money Creation

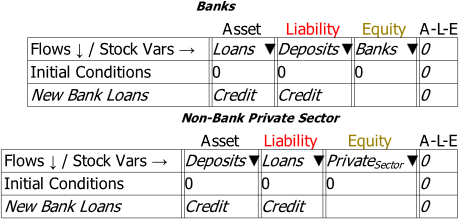

Figure 30 shows the absolute basic accounting for a Credit money system: banks create money by marking up both sides of their balance sheets. They add Credit dollars per year to Deposits, which are their Liabilities; and they add precisely the same sum to Loans, which are their Assets.

For the non-bank private sector, the act of borrowing also increases its Assets and Liabilities equally: Deposits, which are its Assets, rise by Credit dollars per year, and Loans, which are its Liabilities, rise by precisely the same amount. There is therefore no change in the net worth of either the Banking Sector, or the Non-Bank Private Sector from the creation of credit-money.

Figure 30: The fundamental accounting for Credit Money

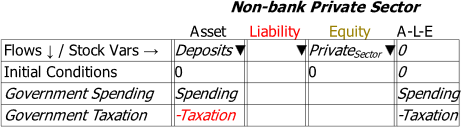

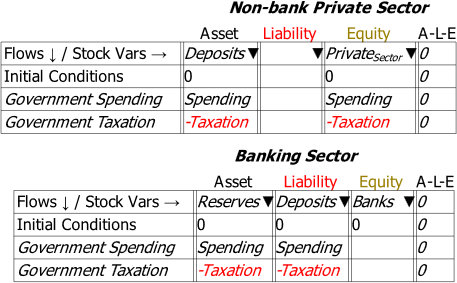

The Government’s role in money creation can be considered the same way, by modelling the two fundamental actions of governments: spending on the non-government private sector (either in the form of purchases or transfers), and taxation of the private sector. Figure 31 adds these to the Non-Bank Private Sector’s Godley Table in Figure 30, but without completing the double-entry.

Figure 31: Introducing Government Spending and Taxation without completing the double-entry

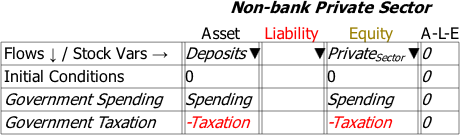

How should it be completed? I hope that it is obvious that the only way to complete this double-entry picture is that government spending increases the Equity—the net financial worth—of the non-bank private sector, while taxation reduces it.

This is shown in Figure 32. Government spending increases the net financial worth—the difference between financial assets and financial liabilities—of the private sector, and taxation reduces it.

Figure 32: The double-entry view of Government Spending and Taxation

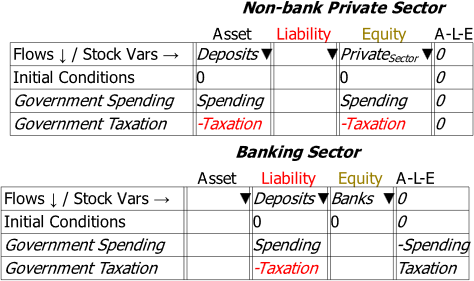

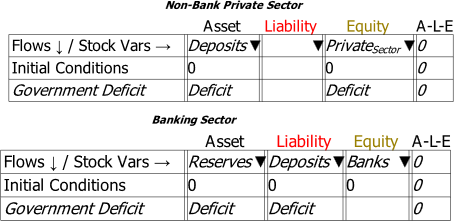

Figure 33 adds the Banking Sector’s Godley Table to the model, but also without completing the double-entry.

Figure 33: Government Spending and Taxation including the Banking Sector without completing the double-entry

The only sensible way to complete this picture is to add an Asset which is increased by government spending (and reduced by taxation)—and this Asset is normally called “Reserves”. That is done in Figure 34, which shows that government spending increases Reserves and Taxation reduces them.

Figure 34: Government Spending increases Reserves as well as Deposits—and taxation reduces them

At this point, several things should be obvious. Firstly, from the Liabilities side of the Banking system’s ledger, government spending creates money in the same way that new bank loans do, by increasing the Deposit accounts of the non-bank private sector. Similarly, taxation destroys money in the same way that the repayment of bank loans does, by reducing the Deposit accounts of the non-bank private sector.

Secondly, from the Assets side, net government spending—when government spending exceeds taxation—also increases the Assets of the banking sector, in the form of Reserves. This again is akin to how net loan growth—when new loans exceed the repayment of old loans—increases the Assets of the banking sector, in the form of Loans.

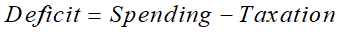

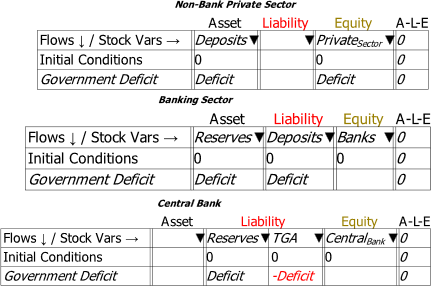

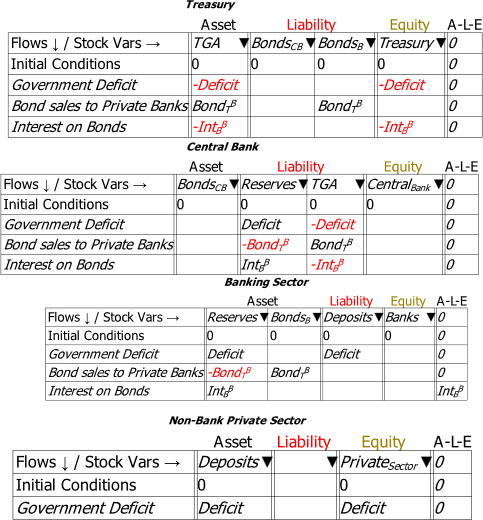

We can simplify the exposition of government money creation by defining the difference between government spending and taxation as the Deficit, and using that in future tables rather than using two rows for government spending and taxation respectively:

It follows therefore that a government Deficit—an excess of government spending over taxation—creates money for the Non-bank Private Sector, and creates Reserves for the Banking Sector, as shown in Figure 35.

Thirdly, since a Deficit adds to the Assets of the Non-bank Private Sector, without creating an offsetting Liability, as is the case with a bank loan, a Deficit increases the net worth—the Equity—of the Non-Bank Private Sector. Far from borrowing money from the private sector, as Neoclassical economists claim, the Deficit creates both money and net financial worth for the private sector.

Figure 35: A Government Deficit increases the net financial worth of the private sector

This is already a dramatically different assertion to the conventional wisdom that, as Mankiw puts it, a budget deficit is financed “by borrowing from the private sector” {Mankiw, 2016 #6107, p. 555}. And unlike the conventional wisdom, this assertion is logically sound. The only way the conventional wisdom could be correct would be if the Deficit had a negative impact on Deposit accounts. Then borrowing would occur as Deposits fell, another Asset of the non-bank private sector—”Loans to the Government”—rose. But in that case, government spending would have to decrease Deposits, and taxation would have to increase them! The conventional wisdom of economics, as is so often the case, is absurdly false.

Instead, just as bank lending creates money by increasing the banking sector’s Assets (Loans) and Liabilities (Deposits) simultaneously, a government deficit creates money by increasing the banking sector’s Assets (Reserves) and Liabilities (Deposits) simultaneously.

This leads to a general principle for money creation: since money is predominantly the Deposit accounts of the Non-Bank Private Sector, to create money, a financial operation must increase both the Assets and the Liabilities of the Banking Sector.

For banks, the process is easy—and this is why banks offer Deposit accounts in the first place. When a bank creates a loan, it marks up both sides of its balance sheet: it increases its Assets by adding to Loans, and it increases its Liabilities by adding to its customer Deposits. This is not possible for a Non-Bank Financial Institution: it can reallocate funds between its Assets, and gain when Assets increase in value, but it can’t increase the value of its Assets by its own operations. Banks can—so long as they can find willing borrowers.

The process of government money creation is more complicated than that of credit money creation, because the government can’t directly write up bank Assets and Liabilities. Instead, it has to increase a bank Asset—Reserves—after which banks will then allocate the same sums to the Deposit accounts of their customers.

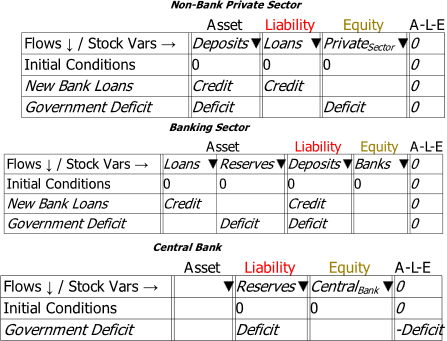

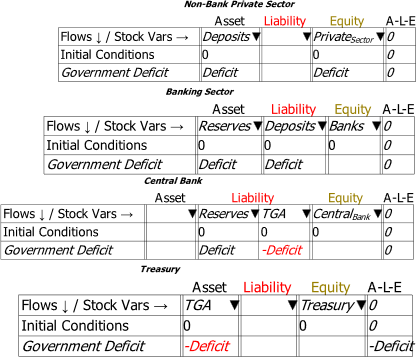

How are Reserves increased? To show that, we need to introduce a third Godley Table, that of the Central Bank. That is done in Figure 36, but without completing the double-entry logic.

Figure 36: Introducing the Central Bank without completing the double-entry

How do we balance that row? We could show this as negative equity for the Central Bank—if, as is the practice amongst many advocates of MMT (Modern Monetary Theory), we consolidated the Central Bank and the Treasury into one entity. But there’s no need to make that simplification with Minsky. We can, instead, show the financial sector in its realistic complexity, by adding another Liability of the Central Bank—the “deposit account” of the Treasury at the Central Bank. This is called the “Consolidated Revenue Fund” (CRF) in the UK, and the “Treasury General Account” in the USA (TGA). I use the American acronym in Figure 37.

Figure 37: The Central Bank with double-entry completed and the Treasury TGA introduced

Reserves rise because of a transfer of funds from the TGA to Reserves. To show how these funds are generated, we need to add the Treasury’s Godley Table. That is done in Figure 38, again without completing the double-entry.

Figure 38: The Treasury Table introduced, without completing the double-entry

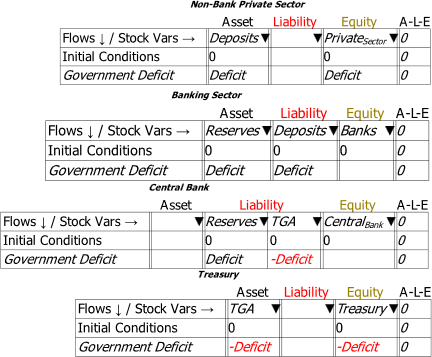

I hope it’s obvious that the only way to balance this line is the make the second entry in the Treasury’s Equity. That is done in Figure 39, which shows that the Treasury’s position is the exact opposite of the Non-Bank Private Sector’s: the positive Equity that the Deficit generates for the Private Sector is created by the Treasury going into identical negative Equity.

Figure 39: The completed basic picture of Government money creation

This simple picture appears unnatural to many people on first sight: what is the government doing, going into negative equity? Isn’t that a bad thing?

In fact, the government being in negative financial equity is the essence of fiat money. Banks create credit money by expanding their Assets and Liabilities equally; this results in a matching expansion of the non-bank private sector’s Liabilities and Assets. Governments create fiat money by going into negative Equity, which creates matching positive Equity for the non-bank private sector.

This can only work in the places in which a government’s liabilities are accepted as money, which define the locations in which it is the government. This is especially so for government operations on bank accounts. Sometimes, one country’s notes and coins are accepted as means of payment in another—you can sometimes use Euros to buy goods in Hungary, for example. But only the Hungarian government can directly add to Hungarian bank accounts by putting more Forints into them via government spending than it debits from them via taxation.

It is also of the essence of financial assets—claims on other entities—that the sum of all financial assets is zero. If one entity is in positive financial equity, then all other entities in an economy as in precisely the same negative financial equity with respect to it. What entity can sustain permanent negative financial equity? Not banks, because, by definition, banks must be in positive financial equity: a bank whose liquid liabilities exceed its liquid assets is bankrupt. The non-bank private sector can sustain negative financial equity, if its income is sufficient to service its debts, but it’s not a comfortable situation for individuals or companies to have liabilities that exceed their assets.

But a government, whose liabilities are money in its country, can always service its net negative financial position because it creates its own money. Finally, fiat money is backed by the extensive nonfinancial assets of a government: the unalienated land, the buildings, infrastructure, military, etc., of a nation state. There is, in other words, no problem with a government being in negative financial equity with respect to its own currency. It also means that, by running a sufficiently large deficit, it can ensure that both the Banking Sector and the Non-Bank Private Sector are in positive equity.

At this absolutely fundamental level then, net government spending does not involve borrowing from the private sector, and in fact it creates fiat money for the private sector. But what about government bonds? How do they change the picture? Don’t they mean that the government is borrowing from the private sector?

-

Government Bond Sales

One obvious consequence of the fundamental situation outlined above is that the Treasury’s account at the Central Bank must go negative. In and of itself, this isn’t a problem, since the Treasury and the Central Bank are both wings of the government, and in terms of where the Central Bank’s income is remitted, the Treasury is the effective owner of the Central Bank. It also has no implications for the solvency of the Central Bank, since the negative value of the TGA is precisely offset by the positive value of Reserves. Finally, as Central Banks themselves acknowledge {Bholat, 2016 #6037}, unlike a private bank, it is not necessary for a Central Bank to be in positive equity.

However, virtually all governments have passed laws requiring the TGA to not go negative—and this is the real function of Treasury Bond sales. The upshot of these laws is that Treasuries are required to sell bonds equivalent in value to the deficit, plus interest on existing bonds.

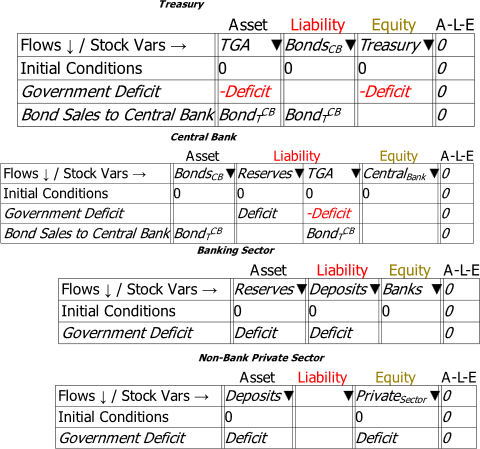

I’ll introduce government bond sales in the simplest possible way—as a sale of a bond to the Central Bank. This is in fact illegal in most countries, since they have also enacted laws that forbid the Central Bank from buying Bonds directly from the Treasury. But there is absolutely no practical impediment to this operation. It also has the side effect that interest payments are unnecessary: in most countries, the Treasury doesn’t pay interest on bonds owned by the Central Bank, and in those which do, the interest income is remitted back to the Treasury anyway. Therefore, interest payments on bonds—the cause of much angst in mainstream economics—can be omitted from the model.

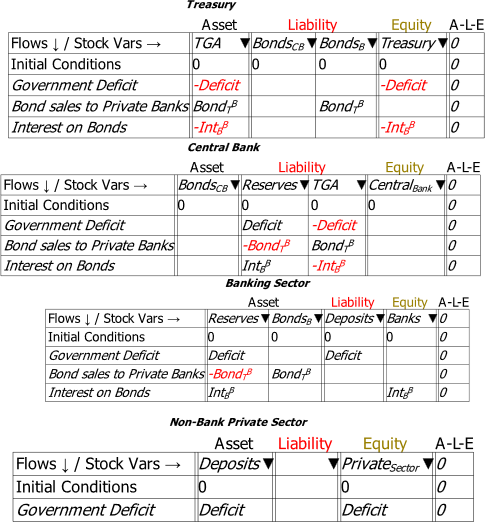

This hypothetical situation is shown in Figure 40. If the value of bonds sold by the Treasury to the Central Bank—shown as the flow —was equal to the Deficit, then the TGA would remain positive (or at least non-negative). This makes no practical difference to fiat money creation—that relies solely upon the Treasury going into negative equity—but is an aesthetic improvement on the situation shown in Figure 39, in that both Liability accounts of the Central Bank (Reserves and the TGA) would be positive. The Central Bank also has positive Assets, whereas in Figure 39 they are zero.

Figure 40: Treasury Bond Sales Direct to the Central Bank

The upshot of this arrangement for the Banking Sector is that the Asset that Deficits generate for it—Reserves—don’t normally earn income (by “normally” I mean “before the “Global Financial Crisis”). I suspect this detail—and not any desire to force prudence upon government money creation—is why most countries have made direct purchases of Treasury Bonds by the Central Bank illegal. Instead, these laws require the Treasury to sell Bonds to the private banks (and primary dealers), with the Central Bank then able to buy bonds from private banks in the “secondary market”.

The “magic” of this arrangement for the Banks is that the funds that private banks use to buy Bonds are created by the deficit itself—both the current deficit and the accumulation of past deficits known as government debt. Banks swap non-income-earning and non-tradeable Reserves for income-earning and tradeable Treasury Bonds. Since the Treasury does have to pay interest on bonds owned by the non-government sector, the act of selling Bonds to the Private Banks also necessitates paying interest on existing Bonds—which is otherwise known as existing Government debt. This generates an income stream for the Banking Sector.

Figure 41 shows this legally required situation, without completing the double-entry details for the impact of interest on bonds for Private Banks. It should be obvious that this payment of interest adds to the net worth of the Banking Sector. And, just as the positive equity from the deficit for the non-bank private sector is created by the Treasury going into negative equity, the positive equity for the Banking Sector from government interest payments is also created by the Treasury going into negative equity.

Figure 41: Bond Sales to Private Banks, without completing the double-entry

A comparison of Figure 39 to Figure 40 and Figure 41 shows how absurd it is to describe the Treasury selling Bonds to the Banking Sector as the Treasury borrowing from the Banking Sector.

Neither arrangement is needed for the Treasury to create fiat money: the deficit alone does that, as Figure 39 shows, and it is financed by the Treasury going into negative equity, not by it selling Bonds to anyone. The only thing preventing Figure 39 from being the normal situation is a law requiring the TGA to not go into overdraft; if that law were repealed, there would be no need for Bond sales at all. Similarly, the only thing preventing Figure 40—direct Treasury bond sales to the Central Bank—is a law prohibiting it. These laws benefit the Banking Sector by letting it earn interest income on the Asset created for it by the Treasury, rather than (normally) not earning interest on Reserves.

Figure 42 completes the picture by showing interest on bonds as increasing the Equity of the Banks. It is then obvious that, just as the deficit creates net equity for the non-bank private sector, the payment of interest on bonds creates net equity for the banking sector.

Figure 42: Treasury Bond sales complicate the process, but don’t change the nature of fiat money

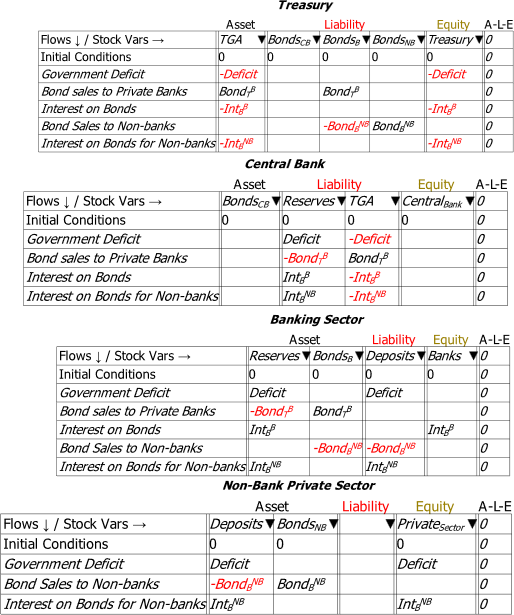

The final operation needed to complete the basic picture of government finances is the sale of Treasury Bonds by Banks to the non-bank private sector. Most of these sales are to Non-Bank Financial Institutions (NBFIs), but for simplicity I simply show this as a sale to the Non-Bank Private Sector in Figure 43. Once again, it would be ridiculous to describe this sale of a financial asset by the Banking Sector to the Non-bank Private Sector as “the government borrowing from the private sector”, but that’s how it’s described by Neoclassical economists.

Figure 43: Bond Sales to Non-Banks by Banks

However, this operation is the only type of Bond sale that affects the quantity of money, and it reduces it rather than increasing it: Deposit accounts at banks fall, while the Non-bank Private Sector’s holdings of an income-earning Asset rise. The sale of Treasury Bonds by Banks to the Non-bank Private Sector—mainly to Non-Bank Financial Institutions (NBFIs)—thus destroys money.

We can now combine this model of fiat money creation—for that is what a Deficit actually is—with the model of credit money creation outlined in the previous chapter to show the real-world consequences of misunderstanding money creation. There is no better indication of the negative impact of mainstream misunderstandings about money than its role in causing the Great Depression.