Solow noted that DSGE models have “a single representative consumer optimizing over infinite time with perfect foresight or rational expectations, in an environment that realizes the resulting plans more or less flawlessly through perfectly competitive forward-looking markets for goods and labor, and perfectly flexible prices and wages” (Solow 2003, Emphasis added). This bizarre construct is the consequence of the theoretical failure that lies below the apparent success of deriving macroeconomics from microeconomics.

This is chapter four of my draft book Rebuilding Economics from the Top Down. The previous chapter was The Impossibility of Microfoundations for Macroeconomics, which is published here on Patreon and here on Substack

If you like my work, please consider becoming a paid subscriber from as little as $10 a year on Patreon, or $5 a month on Substack.

PS Word doesn’t export footnotes or endnotes to blogs, so I’ve inserted footnote text here inside brackets [] and formatted them in italic

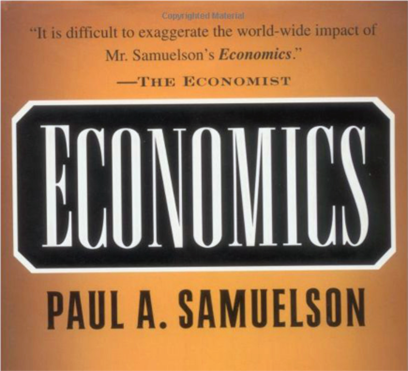

Neoclassical theory has an elaborate and internally consistent model of consumption by an individual consumer, from which it can prove, given its “Axioms of Revealed Preference” (Samuelson 1948), that the individual’s demand curve slopes down [Strictly speaking this is the “Hicksian Compensated Demand Curve”, which I explain in Chapter 3 of Debunking Economics (Keen 2011), “The Calculus of Hedonism”.]. An individual demand curve therefore obeys the so-called “Law of Demand” that, to cite Alfred Marshall:

There is then one general law of demand: The greater the amount to be sold, the smaller must be the price at which it is offered in order that it may find purchasers; or, in other words, the amount demanded increases with a fall in price, and diminishes with a rise in price. (Marshall 1890 [1920], p. 99)

Marshall thought that what applied to the individual would also apply to the market, because the “peculiarities in the wants of individuals” would cancel each other out, so that market demand would also fall as the price rose:

In large markets, then—where rich and poor, old and young, men and women, persons of all varieties of tastes, temperaments and occupations are mingled together—the peculiarities in the wants of individuals will compensate one another in a comparatively regular gradation of total demand. (Marshall 1890 [1920], p. 98)

The bad news, which was discovered decades later by a number of mathematical economists (Gorman 1953; Samuelson 1956; Sonnenschein 1972, 1973a, 1973b; Shafer and Sonnenschein 1982; Mantel 1974, 1976; Debreu 1974), was that this was not true: summing the demand curves from many individuals, each of whose personal demand curves obeyed the “Law of Demand”, can generate a market demand curve that does not necessarily slope downwards. (It can instead adopt any shape at all that you can draw that doesn’t cross itself, and which doesn’t generate two quantity outputs for one relative price input. This does not mean that empirically derived demand curves behave this way, by the way—since empirical data will inherently include the effect of the distribution of income. What it does mean is that Neoclassical economists cannot derive a core aspect of their model from their own core assumptions.)

The only way to avoid this result was to make the absurd assumptions that changes in relative prices did not affect the distribution of income, and that changes in the distribution of income had no impact upon market demand. This was put in terms of Engel curves by Gorman [Engel curves describe how an individual’s expenditure on a given good change with income, while relative prices are held constant. If a good is a necessity, then its Engel curve for a given individual will show this good becoming a smaller and smaller component of the individual’s total expenditure as his/her income rises. If it is a luxury, then its Engel curve for a given individual will show this good becoming a larger and component of the individual’s total expenditure as his/her income rises], who was the first economist to discover this result:

we will show that there is just one community indifference locus through each point if, and only if, the Engel curves for different individuals at the same prices are parallel straight lines. (Gorman 1953, p. 63)

Samuelson, three years later, quite correctly described this result as an “impossibility theorem”:

The common sense of this impossibility theorem is easy to grasp. Allocating the same totals differently among people must in general change the resulting equilibrium price ratio. The only exception is where tastes are identical, not only for all men, but also for all men when they are rich or poor. (Samuelson 1956, p. 5. Emphasis added)

Therefore, the “Law of Demand”, which played such an essential role in Marshall’s reasoning, did not apply to the market demand curve. This invalidated the very foundations of Neoclassical theory, of starting its analysis from the subjective utility of an individual consumer, and the profit-maximizing behaviour of an individual firm. Au contraire, it validated the practice of the preceding Classical school—including the much-loathed and derided Karl Marx—of treating society as consisting of social classes (capitalists, landlords, workers, bankers), each with different income sources (profits, rents, wages, interest) and differing consumption patterns (a Protestant abstemious focus on investment, profligate consumption, subsistence, and Veblenian conspicuous consumption). As Alan Kirman later put it:

If we are to progress further we may well be forced to theorise in terms of groups who have collectively coherent behaviour. Thus demand and expenditure functions if they are to be set against reality must be defined at some reasonably high level of aggregation. The idea that we should start at the level of the isolated individual is one which we may well have to abandon. There is no more misleading description in modern economics than the so-called microfoundations of macroeconomics which in fact describe the behaviour of the consumption or production sector by the behaviour of one individual or firm. (Kirman 1989, p. 138. Emphasis added)

This result—now known as the Sonnenschein-Mantel Debreu Theorem—showed that, not only can macroeconomics not be derived from microeconomics, but that even microeconomics itself—the analysis of demand for a single market—cannot be derived from microeconomics—the theory of the consumption behaviour of an individual.

This realisation should have been a moment of revolutionary change for economics. The “marginal revolution”, which rejected the objectively-based theory of value of the Classical School and replaced it with a subjective theory of the individual, had failed its first hurdle, the jump from the analysis of the isolated individual to the aggregate. Though the Classical School had its own problems (Keen 1993a, 1993b), the Neoclassical School was not a viable alternative, but instead was a dead-end.

Needless to say, that is not how Neoclassical economists—even those who discovered this result—reacted. Instead, faced with a result that meant they had to either abandon their paradigm or make ridiculous assumptions to hang onto it, they did the latter.

Gorman’s necessary and sufficient condition noted above means that the very concept of a market system disappears: it is equivalent to assuming that there is only one consumer, and only one commodity. But if there is, how can there be relative prices, let alone a market? Rather than being a model of an actual macroeconomy, this is a model of Robinson Crusoe, alone on his island, where all he can harvest and eat is coconuts.

And yet Gorman described his condition as “intuitively reasonable”, while simultaneously demonstrating that it was absurd:

The necessary and sufficient condition quoted above is intuitively reasonable. It says, in effect, that an extra unit of purchasing power should be spent in the same way no matter to whom it is given. (Gorman 1953, pp. 63-64. Emphasis added)

That is not “intuitively reasonable”: it is intuitively bonkers. Giving “an extra unit of purchasing power” to a billionaire will obviously result in totally different consumption than if it were given to a single mother.

Equally bonkers was Samuelson’s ultimate assumption that the entire economy could be treated as one big, happy family, in which income was redistributed prior to consumption, so that everyone was happy:

If within the family there can be assumed to take place an optimal reallocation of income so as to keep each member’s dollar expenditure of equal ethical worth, then there can be derived for the whole family a set of well-behaved indifference contours relating the totals of what it consumes: the family can be said to act as if it maximizes such a group preference function.

The same argument will apply to all of society if optimal reallocations of income can be assumed to keep the ethical worth of each person’s marginal dollar equal. (Samuelson 1956, p. 21. Bold emphasis added)

If? This is possibly the biggest “if” in the history of academic scholarship. Can this be assumed in the case of the United States of America—possibly the most fractious superpower in the history of human civilisation? The obvious answer is “of course not!”—and this applies to American families, let alone the entire country. But the obvious absurdity of this assumption doesn’t cause Samuelson one iota of worry or doubt. He immediately continued on with:

By means of Hicks’s composite commodity theorem and by other considerations, a rigorous proof is given that the newly defined social or community indifference contours have the regularity properties of ordinary individual preference contours (nonintersection, convexity to the origin, etc.)…

Our analysis gives a first justification to the Wald hypothesis that market totals satisfy the “weak axiom” of individual preference…

The foundation is laid for the “economics of a good society.” (Samuelson 1956, pp. 21-22. Emphasis added)

“A rigorous proof”? After possibly the most absurd assumption ever, even in a discipline renowned for absurd assumptions? It is more rigor mortis of the mind than intellectual rigour, that Samuelson, having proven that his endeavour to derive market demand from a logically coherent theory of individual demand that he developed (Samuelson 1938, 1948) had failed, could not bring himself to accept this, and instead made a manifestly false assumption to hide this contrary result. [This is not an unusual failing, unfortunately: Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (Kuhn 1970) shows that this is the norm in science. Once they are committed to a paradigm, it is extremely rare that scientists ever change their minds when confronted with evidence that contradicts it: they instead search for ways to modify the paradigm to cope with the irreconcilable anomaly. Max Planck, the discoverer of quantum mechanics, remarked on this poignantly in his autobiography: “It is one of the most painful experiences of my entire scientific life that I have but seldom—in fact, I might say, never—succeeded in gaining universal recognition for a new result, the truth of which I could demonstrate by a conclusive, albeit only theoretical proof” (Planck 1949, p. 22).]

Bizarrely, if his assumption of “optimal reallocations of income … to keep the ethical worth of each person’s marginal dollar equal” had indeed laid the foundation “for the ‘economics of a good society'”, then Samuelson had proven that this “good society” must have a benevolent dictatorship as its helm, so that those “optimal reallocations” can occur. Capitalism, to behave as Neoclassical economists think it does, must be run by a socialist dictator.

Unfortunately, Gorman’s and Samuelson’s bonkers reactions became the norm, out of which emerged the “representative agent”.

Students are generally given a mendacious explanation of this manifestly absurd construct. In the most childish of such texts—such as Gregory Mankiw’s Principles of Microeconomics (Mankiw 2001)—students are simply told that the market demand curve is the sum of individual demand curves:

MARKET DEMAND AS THE SUM OF INDIVIDUAL DEMANDS. The market demand curve is found by adding horizontally the individual demand curves. At a price of $2, Catherine demands 4 ice-cream cones, and Nicholas demands 3 ice-cream cones. The quantity demanded in the market at this price is 7 cones. (Mankiw 2001, p. 71)

Samuelson’s own textbook—now maintained by William Nordhaus, whose work on climate change is the worst “research” I have ever encountered (Keen 2020)—delivers the most blatant misrepresentation of these results:

Market Demand: Our discussion of demand has so far referred to “the” demand curve. But whose demand is it? Mine? Yours? Everybody’s? The fundamental building block for demand is individual preferences. However, in this chapter we will always focus on the market demand, which represents the sum total of all individual demands. The market demand is what is observable in the real world.

The market demand curve is found by adding together the quantities demanded by all individuals at each price.

Does the market demand curve obey the law of downward-sloping demand? It certainly does. (Samuelson and Nordhaus 2010, p. 48. Boldface emphasis added)

Only slightly less deceptively, Hal Varian’s Intermediate Microeconomics: A Modern Approach implies that the derivation of a market demand curve from individual demand curves is possible, but the process is too difficult for middle-level undergraduates to understand:

Since each individual’s demand for each good depends on prices and his or her money income, the aggregate demand will generally depend on prices and the distribution of incomes. However, it is sometimes convenient to think of the aggregate demand as the demand of some “representative consumer” who has an income that is just the sum of all individual incomes. The conditions under which this can be done are rather restrictive, and a complete discussion of this issue is beyond the scope of this book. (Varian 2010, p. 271. Emphasis added.)

Mas-Colell’s gargantuan postgraduate text Microeconomic Theory (Mas-Colell, Whinston, Green, and El-Hodiri 1996) provides the most honest statement of the theorem. In a section accurately described as “Anything Goes: The Sonnenschein-Mantel-Debreu Theorem“, it states that a market demand curve can have any shape at all:

Can … [an arbitrary function] … coincide with the excess demand function of an economy for every p [price]… Of course … [the arbitrary function] must be continuous, it must be homogeneous of degree zero, and it must satisfy Walras’ law. But for any [arbitrary function] satisfying these three conditions, it turns out that the answer is, again, “yes”. (Mas-Colell, Whinston et al. 1995, p. 602)

But Mas-Colell also uses Samuelson’s escape clause, of a “benevolent central authority” that redistributes income prior to trade, with nary a word on how absurd an assumption this is to apply to a market economy: [This is especially ridiculous coming from a school of thought in economics that champions a libertarian vision of capitalism—that it would be better off with no government intervention whatsoever.]

Let us now hypothesize that there is a process, a benevolent central authority perhaps, that, for any given prices p and aggregate wealth function w, redistributes wealth in order to maximize social welfare…

If there is a normative representative consumer, the preferences of this consumer have welfare significance and the aggregate demand function can be used to make welfare judgments by means of the techniques [used for individual consumers]. In doing so however, it should never be forgotten that a given wealth distribution rule [imposed by the “benevolent central authority”] is being adhered to and that the “level of wealth” should always be understood as the “optimally distributed level of wealth”. (Mas-Colell, Whinston, and Green 1995, pp. 117-118. Emphasis added)

It is therefore little wonder that student economists, taught in this fashion ever since 1953, saw no problem with the concept of a “representative agent”, and ultimately built models of the macroeconomy that they believed were consistent with microeconomics.

Older and more realistic hands like Solow could see through this subterfuge, but they were ignored until reality, in the form of the Global Financial Crisis, exposed the inadequacy of the foundations that no amount of adding of “frictions” could overcome.

The DSGE model populates its simplified economy with exactly one single combined worker, owner, consumer, everything else who plans ahead carefully, lives forever; and … there are no conflicts of interest, no incompatible expectations, no deceptions… Under pressure from skeptics and from the need to deal with actual data, DSGE modelers have worked hard to allow for various market frictions and imperfections like rigid prices and wages, asymmetries of information, time lags and so on… But the basic story always treats the whole economy as if it were like a person trying consciously and rationally to do the best it can on behalf of the representative agent, given its circumstances. This cannot be an adequate description of a national economy, which is pretty conspicuously not pursuing a consistent goal. A thoughtful person faced with that economic policy based on that kind of idea might reasonably wonder what planet he or she is on. (Solow 2010, p. 13. Emphasis added)

Despite these existential problems, Neoclassical economists have developed an answer of sorts to Solow and Kirman, with what are now called HANKs: “Heterogeneous Agent New Keynesian” models. These consider at least two different types of agents, with potentially differing income sources, consumption, and expectations (Chari and Kehoe 2008; Kaplan, Moll, and Violante 2018; Acharya and Dogra 2020; Alves, Kaplan, Moll, and Violante 2020; Acharya, Challe, and Dogra 2023). It can at least be asserted that they are treating “demand and expenditure functions … at some reasonably high level of aggregation” (Kirman 1989, p. 138).

But there is no answer to the next issue: the incompatibility of the real-world cost structure of firms with the Neoclassical theory of profit maximization.

Acharya, Sushant, Edouard Challe, and Keshav Dogra. 2023. ‘Optimal Monetary Policy According to HANK’, The American Economic Review, 113: 1741-82.

Acharya, Sushant, and Keshav Dogra. 2020. ‘Understanding Hank: Insights from a Prank’, Econometrica, 88: 1113-58.

Alves, Felipe, Greg Kaplan, Benjamin Moll, and Giovanni L. Violante. 2020. ‘A Further Look at the Propagation of Monetary Policy Shocks in HANK’, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 52: 521-59.

Chari, V. V., and Patrick J. Kehoe. 2008. ‘Response from V. V. Chari and Patrick J. Kehoe’, The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22: 247-50.

Debreu, Gerard. 1974. ‘Excess demand functions’, Journal of mathematical economics, 1: 15-21.

Gorman, W. M. 1953. ‘Community Preference Fields’, Econometrica, 21: 63-80.

Kaplan, Greg, Benjamin Moll, and Giovanni L. Violante. 2018. ‘Monetary Policy According to HANK’, The American Economic Review, 108: 697-743.

Keen, Steve. 1993a. ‘The Misinterpretation of Marx’s Theory of Value’, Journal of the history of economic thought, 15: 282-300.

———. 1993b. ‘Use-Value, Exchange Value, and the Demise of Marx’s Labor Theory of Value’, Journal of the history of economic thought, 15: 107-21.

———. 2011. Debunking economics: The naked emperor dethroned? (Zed Books: London).

———. 2020. ‘The appallingly bad neoclassical economics of climate change’, Globalizations: 1-29.

Kirman, Alan. 1989. ‘The Intrinsic Limits of Modern Economic Theory: The Emperor Has No Clothes’, Economic Journal, 99: 126-39.

Kuhn, Thomas. 1970. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (University of Chicago Press: Chicago).

Mankiw, N. Gregory. 2001. Principles of Microeconomics (South-Western College Publishers: Stamford).

Mantel, Rolf R. 1974. ‘On the Characterization of Aggregate Excess Demand’, Journal of Economic Theory, 7: 348-53.

———. 1976. ‘Homothetic Preferences and Community Excess Demand Functions’, Journal of Economic Theory, 12: 197-201.

Marshall, Alfred. 1890 [1920]. Principles of Economics ( Library of Economics and Liberty).

Mas-Colell, A., M. D. Whinston, J. R. Green, and M. El-Hodiri. 1996. “Microeconomic Theory.” In, 108-13. Wien: Springer-Verlag.

Mas-Colell, Andreu, Michael Dennis Whinston, and Jerry R. Green. 1995. Microeconomic theory (Oxford University Press: New York :).

Planck, Max. 1949. Scientific Autobiography and Other Papers (Philosophical Library; Williams & Norgate: London).

Samuelson, P. A. 1938. ‘A Note on the Pure Theory of Consumer’s Behaviour’, Economica, 5: 61-71.

———. 1948. ‘Consumption theory in terms of revealed preference’, Economica, 15: 243-53.

Samuelson, Paul A. 1956. ‘Social Indifference Curves’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 70: 1-22.

Samuelson, Paul A., and William D. Nordhaus. 2010. Economics (McGraw-Hill: New York).

Shafer, Wayne, and Hugo Sonnenschein. 1982. ‘Chapter 14 Market demand and excess demand functions’, Handbook of Mathematical Economics, 2: 671-93.

Solow, R. M. 2010. “Building a Science of Economics for the Real World.” In House Committee on Science and Technology Subcommittee on Investigations and Oversight. Washington.

Solow, Robert M. 2003. “Dumb and Dumber in Macroeconomics.” In Festschrift for Joe Stiglitz. Columbia University.

Sonnenschein, Hugo. 1972. ‘Market Excess Demand Functions’, Econometrica, 40: 549-63.

———. 1973a. ‘Do Walras’ Identity and Continuity Characterize the Class of Community Excess Demand Functions?’, Journal of Economic Theory, 6: 345-54.

———. 1973b. ‘The Utility Hypothesis and Market Demand Theory’, Western Economic Journal, 11: 404-10.

Varian, Hal R. 2010. Intermediate Microeconomics: A Modern Approach (W. W. Norton & Company: New York).

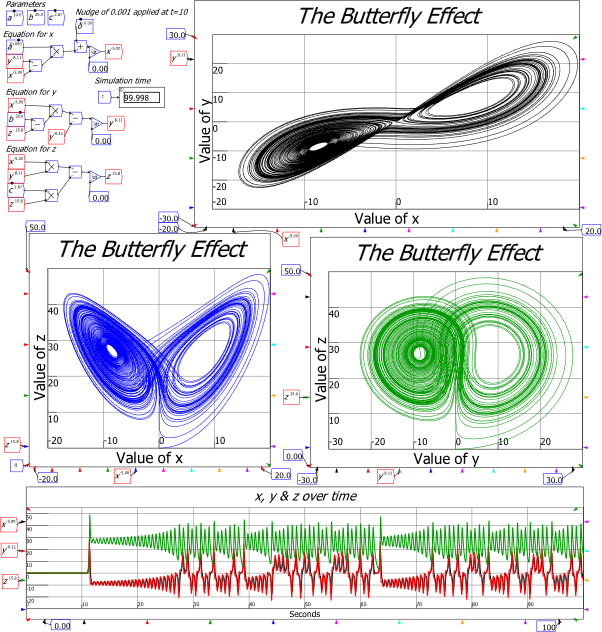

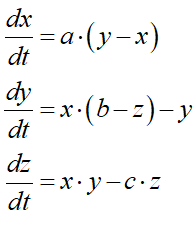

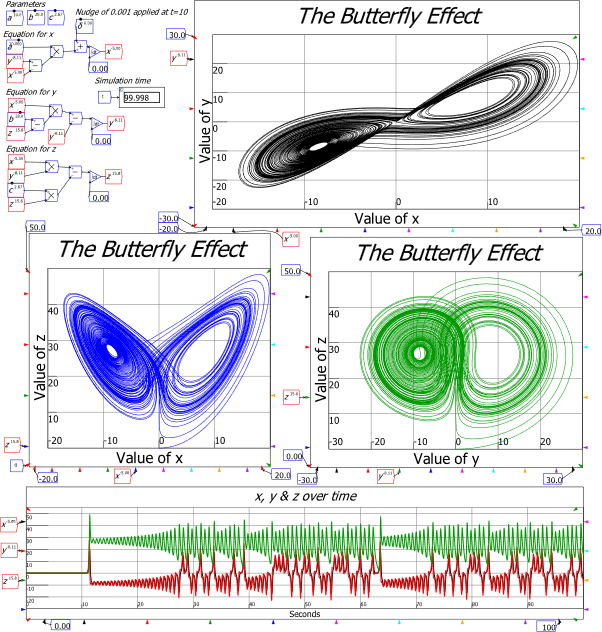

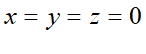

, which were the initial condition of the simulation shown in Figure 4. I then nudged the x-value 0.001 away from its equilibrium at the ten second mark. After this disturbance, the system was propelled away from this unstable equilibrium towards the other two—the “eyes” in the three phase plots. These equilibria are “strange attractors”, which means that they describe regions that the system will never reach—even though they are also equilibria of the system.

, which were the initial condition of the simulation shown in Figure 4. I then nudged the x-value 0.001 away from its equilibrium at the ten second mark. After this disturbance, the system was propelled away from this unstable equilibrium towards the other two—the “eyes” in the three phase plots. These equilibria are “strange attractors”, which means that they describe regions that the system will never reach—even though they are also equilibria of the system.