Most people who haven’t studied economics expect economists to be experts on money—after all, isn’t that what economics is about? In fact, Neoclassical macroeconomics ignores banks, and private debt, and money. Neoclassical economists justified this omission, at least before the 2007 Global Financial Crisis, with the assertion that banks—and their products, debt and money—were largely irrelevant to macroeconomics.

Ex-Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke put it this way, when he dismissed Irving Fisher’s argument that the Great Depression was caused by a process that Fisher termed “debt-deflation”:

Fisher envisioned a dynamic process in which falling asset and commodity prices created pressure on nominal debtors, forcing them into distress sales of assets, which in turn led to further price declines and financial difficulties… Fisher’s idea was less influential in academic circles, though, because of the counterargument that debt-deflation represented no more than a redistribution from one group (debtors) to another (creditors). Absent implausibly large differences in marginal spending propensities among the groups, it was suggested, pure redistributions should have no significant macroeconomic effects. (Bernanke 2000, p. 24. Emphasis added)

By “pure redistribution”, what Bernanke meant is that, in the Neoclassical model of banking, lending and the repayment of debt transfer money from one group to another—from saver to borrower in the case of lending, and from borrower to saver in the case of repayment—but no new money is created. Unless there is a substantial difference in the rate at which savers and borrowers spend, this model predicts that the macroeconomic impact of a substantial fall in the level of debt—a “debt-deflation”—will be slight.

“Nobel Prize” winner (Offer and Söderberg 2016, Mirowski 2020) Paul Krugman elaborated on this argument in his New York Times column, where he has regularly explained and promoted the “Loanable Funds” model of banking (Krugman 2009, Krugman 2011, Krugman 2011, Krugman 2013, Krugman 2015, Krugman 2015). In this model, banks are intermediaries between “more patient people” who want a return on their savings, and “less patient people” who want to spend more than their incomes at some point in time:

Think of it this way: when debt is rising, it’s not the economy as a whole borrowing more money. It is, rather, a case of less patient people—people who for whatever reason want to spend sooner rather than later—borrowing from more patient people. (Krugman 2012, p. 147)

In this model, lending simply shuffles existing money from one set of people to another: banks take in deposits from some customers, and lend them out as loans to other customers. There is also no relationship between the level of private debt and the amount of money in the economy.

If this

description of how banks operate were correct, the amount of money couldn’t change—just its distribution between the bank accounts of the different customers of the banks. So how could money be created then? In Neoclassical economics, money creation is primarily the province of the government, via what is known as “Fractional Reserve Banking”, or the “Money Multiplier”. A bank, it is asserted, takes in deposits from savers, and then lends out a large fraction of these to borrowers. This lending creates money in an iterative process involving many banks. The amount created is largely determined by the government via its Central Bank, but actions by banks and the non-bank public can only reduce the amount of money created, not increase it. Gregory Mankiw explains it in this way his textbook Macroeconomics:

If the Federal Reserve adds a dollar to the economy and that dollar is held as currency, the money supply increases by exactly one dollar. But as we have seen, if that dollar is deposited in a bank, and banks hold only a fraction of their deposits in reserve, the money supply increases by more than one dollar. As a result, to understand what determines the money supply under fractional–reserve banking, we need to take account of the interactions among (1) the Fed’s decision about how many dollars to create, (2) banks’ decisions about whether to hold deposits as reserves or to lend them out, and (3) households’ decisions about whether to hold their money in the form of currency or demand deposits. (Mankiw 2016, pp. 93-94)

There are three factors that determine the money supply in this model: the “monetary base”, which “is directly controlled by the Federal Reserve”; the fraction of any bank deposits that banks hold on to, which “is determined by the business policies of banks and the laws regulating banks”, and the amount of money the public hold in cash versus the amount they deposit in banks.

The only point in this model at which banks have an active role is their capacity to hold a higher fraction of deposits as reserves than they are required to do by law, and the only impact this can have is to reduce the amount of money created. Bank customers can also reduce the amount of money created by keeping more of their money as cash. The Central Bank therefore has the dominant role in determining the money supply, according to Neoclassical economics. For this reason, in his Essays on the Great Depression, Bernanke blamed the calamity of the Great Depression on the Federal Reserve itself:

our analysis provides the clearest indictment of the Federal Reserve and U.S. monetary policy. Between mid-1928 and the financial crises that began in the spring of 1931, the Fed not only refused to monetize the substantial gold inflows to the United States but actually managed to convert positive reserve inflows into negative growth in the M1 money stock. Thus Fed policy was actively destabilizing in the pre-1931 period… our methods attribute a substantial portion of the worldwide deflation prior to 1931 to these policy decisions by the Federal Reserve. (Bernanke 2000, p. 111)

In contrast, Post Keynesian economists followed Irving Fisher (Fisher 1932, Fisher 1933) and blamed the Great Depression on the disequilibrium dynamics of private debt. Hyman Minsky combined Fisher’s ideas with Keynes’s to develop what he christened the “Financial Instability Hypothesis” (Minsky 1963, Minsky 1975, Minsky 1977, Minsky 1978). Private debt, which Neoclassical economists ignore, was an essential component of Minsky’s analysis of the instability of capitalism. He put it this way:

The natural starting place for analyzing the relation between debt and income is to take an economy with a cyclical past that is now doing well… As the period over which the economy does well lengthens, two things become evident in board rooms. Existing debts are easily validated and units that were heavily in debt prospered; it paid to lever… As a result, over a period in which the economy does well, views about acceptable debt structure change… As this continues the economy is transformed into a boom economy.

Stable growth is inconsistent with the manner in which investment is determined in an economy in which debt-financed ownership of capital assets exists, and the extent to which such debt financing can be carried is market determined. It follows that the fundamental instability of a capitalist economy is upward. The tendency to transform doing well into a speculative investment boom is the basic instability in a capitalist economy. (Minsky 1982, p. 66. Emphasis added)

For rising debt to cause rising economic activity, there must be some mechanism by which rising debt boosts aggregate demand—in contrast to the Neoclassical argument that changes in the level of debt were “pure redistributions” with “no significant macroeconomic effects” (Bernanke 2000, p. 24 ). The Neoclassical “Loanable Funds” and “Fractional-Reserve-Banking—Money Multiplier” models must therefore be wrong: bank lending must somehow create money, and this must also increase aggregate demand.

Post Keynesian economists—and some policy economists in Central Banks as well (Holmes 1969)—have argued for many decades that these Neoclassical models are false, and that banks create money when they lend (Fisher 1933, Schumpeter 1934, Minsky 1963, Moore 1979, Moore 1988, Graziani 1989, Minsky 1990, Minsky and Vaughan 1990, Keen 1995, Moore 1997, Moore 2001, Fontana and Realfonzo 2005, Fullwiler 2013, Werner 2014, Werner 2014), but their protestations were ignored by Neoclassicals. However in 2014, no less an institution than the Bank of England sided with the Post Keynesians (McLeay, Radia et al. 2014, McLeay, Radia et al. 2014, Kumhof and Jakab 2015, Kumhof, Rancière et al. 2015), and stated emphatically that the Neoclassical models of banking—”Loanable Funds”, “Fractional Reserve Banking” and “The Money Multiplier”—were false:

The reality of how money is created today differs from the description found in some economics textbooks:

- Rather than banks receiving deposits when households save and then lending them out, bank lending creates deposits.

- In normal times, the central bank does not fix the amount of money in circulation, nor is central bank money ‘multiplied up’ into more loans and deposits. (McLeay, Radia et al. 2014, p. 1. Emphasis added)

The Bundesbank made a similar pronouncement in 2017:

It suffices to look at the creation of (book) money as a set of straightforward accounting entries to grasp that money and credit are created as the result of complex interactions between banks, non- banks and the central bank. And a bank’s ability to grant loans and create money has nothing to do with whether it already has excess reserves or deposits at its disposal. (Deutsche Bundesbank 2017, p. 13. Emphasis added)

Neoclassical economists could not completely ignore these flat-out contradictions of their models of banking by establishment bodies like Central Banks, but rather than accepting the critique and abandoning their models, their reaction was defensive. For example, Krugman argued that the Bank of England’s paper was nothing new—and therefore it did not challenge the relevance of the Loanable Funds model, even though the model itself was technically wrong:

OK, color me puzzled. I’ve seen a number of people touting this Bank of England paper (pdf) on how banks create money as offering some kind of radical new way of looking at the economy. And it is a good piece. But it doesn’t seem, in any important way, to be at odds with what Tobin wrote 50 years ago … Don’t let monetary realism slide into monetary mysticism! (Krugman 2014. Emphasis added)

Since then, Neoclassical textbooks have continued to teach the Loanable Funds and Fractional Reserve Banking models of banking (Mankiw 2016, pp. 71-76, 89-100), as if there’s nothing wrong in teaching factually incorrect models—as if the change from a model in which banks do not create money, to one in which they do, makes no difference to macroeconomics.

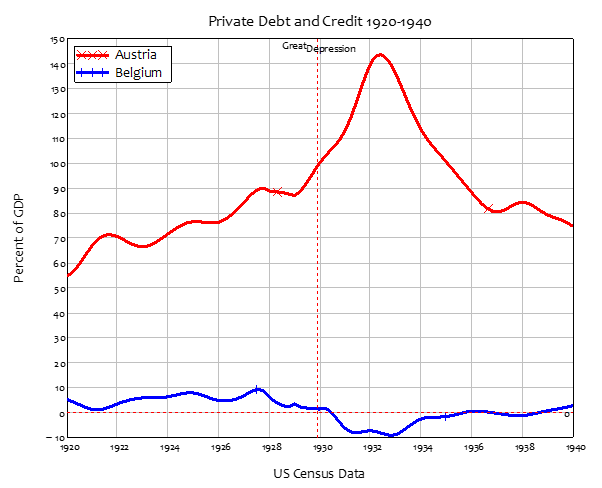

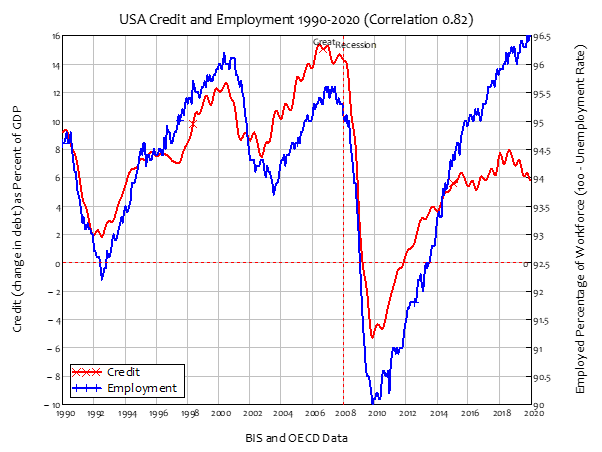

However, the fact that banks create money when they lend has an enormous impact on macroeconomics, and models which pretend that banks don’t create money are utterly inaccurate models of capitalism. This can be seen simply by contrasting Bernanke’s dismissal of Fisher’s debt-deflation explanation for the Great Depression with the data. Bernanke asserted that the change in debt (which he called a “pure redistribution”, following the Loanable Funds model of banking) should have “no significant macroeconomic effects” (Bernanke 2000, p. 24). That can be framed as the statistical hypothesis that the correlation coefficients between the change in private debt and important macroeconomic variables should be not significantly different from zero.

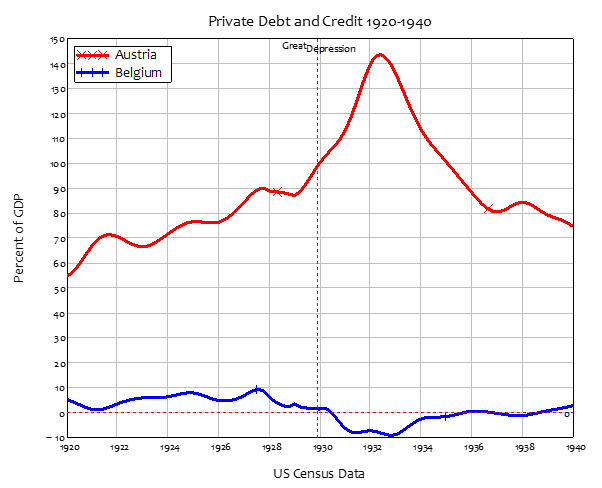

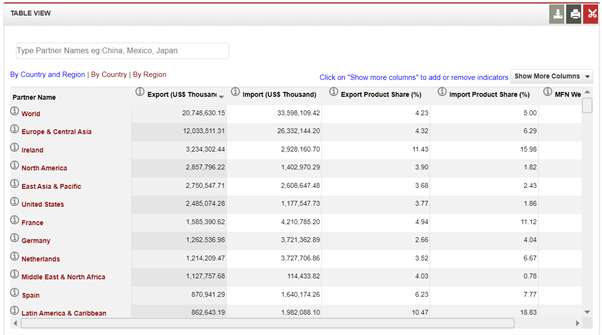

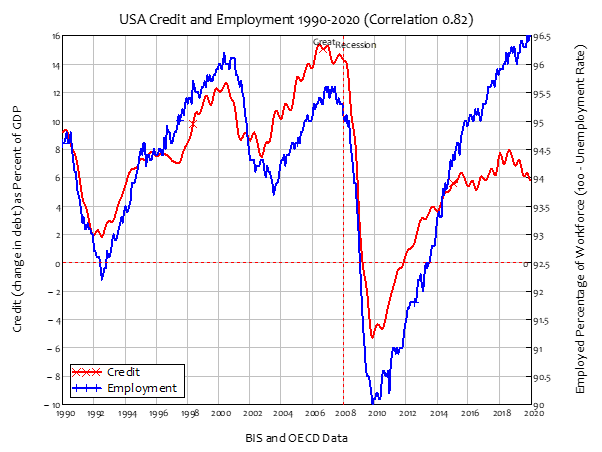

In fact, the correlation between credit (the annual change in private debt, measured in percent of GDP) and employment between 1920 and 1940 was 0.81. Between 1990 and 2020, it was as 0.82 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The correlation between credit and employment across 1990-2020 was 0.82

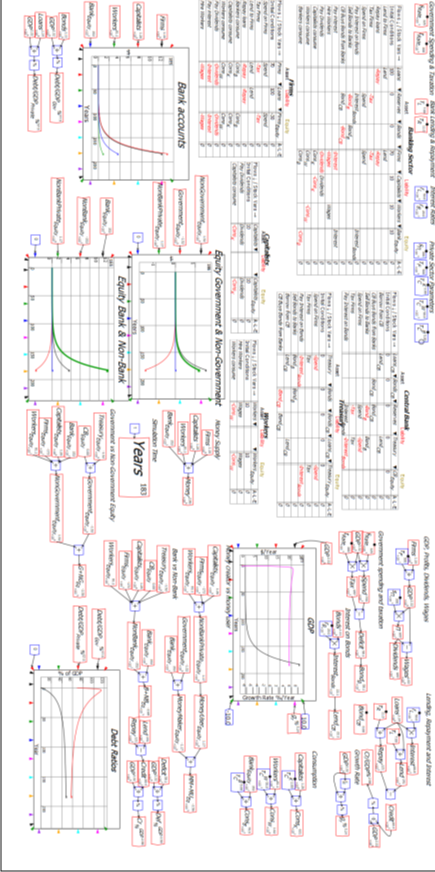

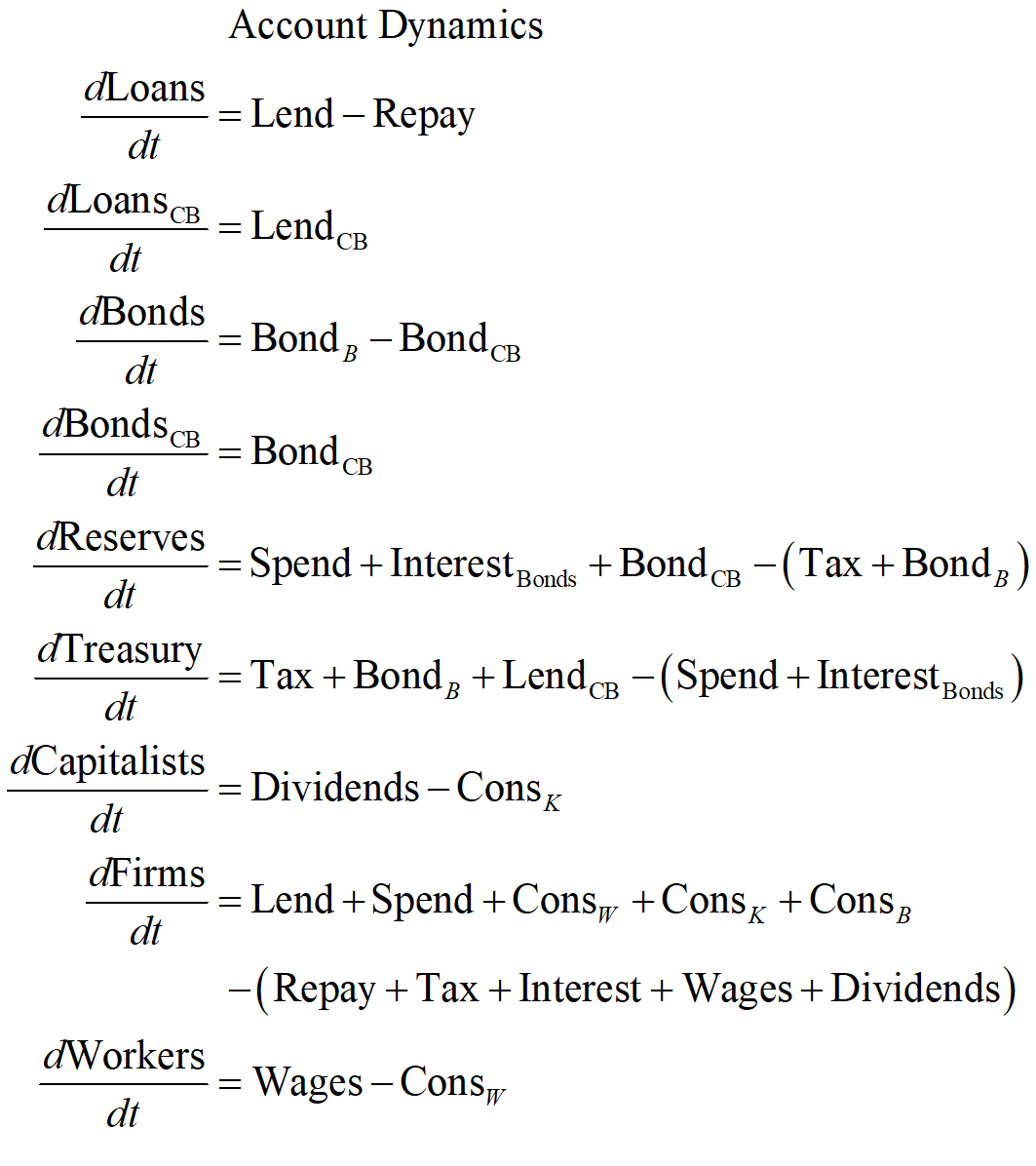

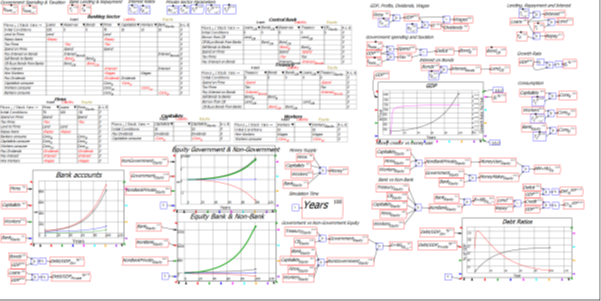

There is therefore a striking anomaly between Neoclassical economic theory and the real world. Let’s investigate this anomaly—and start constructing a new, monetary approach to economics—using one of the new computer software tools I alluded to earlier: the Open Source (that is, free) “system dynamics” program Minsky.

-

Modelling Credit Money in Minsky

Minsky was built to model money, which raises the vexed question “Well, what is money?”. The question is vexed because, especially today, people hold vehement views about what money should be—rather than what it currently is. Some argue that gold is money (Sennholz 1975); others assert that crypto-currencies should be money (Chambers 2019). However, in practical terms, gold and cryptocurrencies primarily fulfil only the last of the three accepted characteristics of money: a unit of account, a means of payment, and a store of value. The first two characteristics, which are essential to commerce in a market economy, are today fulfilled predominantly by national currencies.

Secondly, the vast majority of transactions today involve, not transfers of physical notes and coins, but electronic transfers between bank accounts, in return for goods. This is an exchange of records in a computer database, in return for a commodity or a service. The Post Keynesian monetary theorist Augusto Graziani pointed out that this meant that “any monetary payment must therefore be a triangular transaction, involving at least three agents, the payer, the payee, and the bank” (Graziani 1989, p. 3).

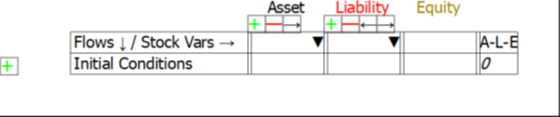

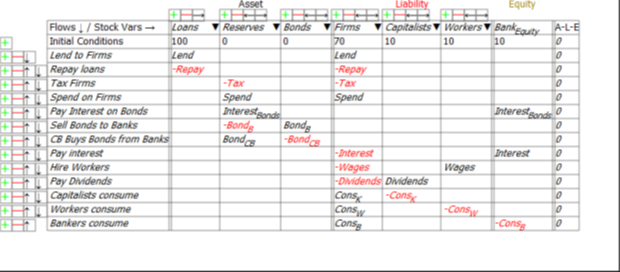

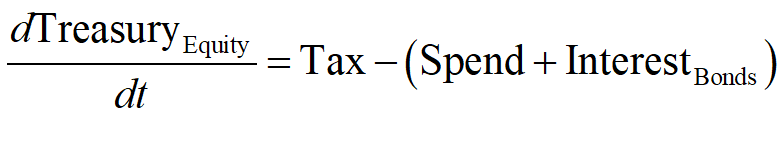

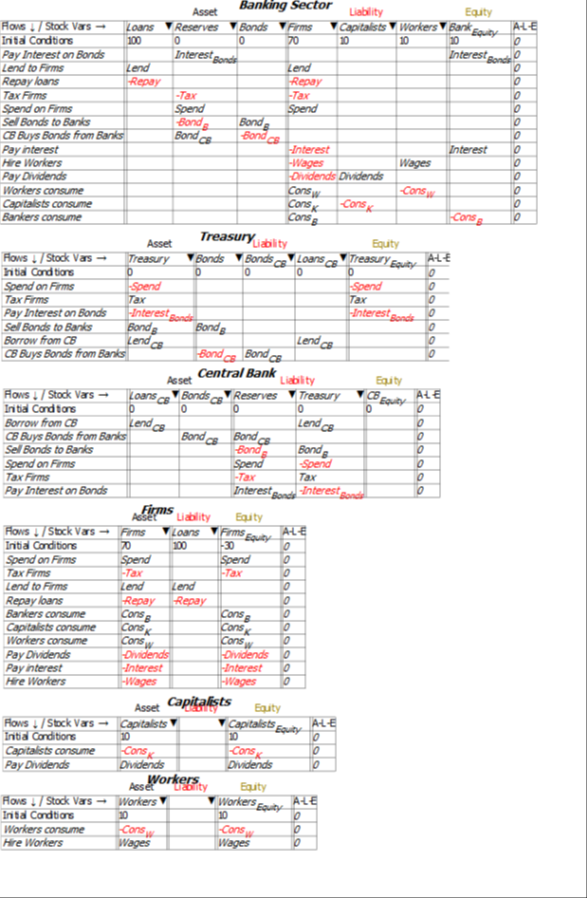

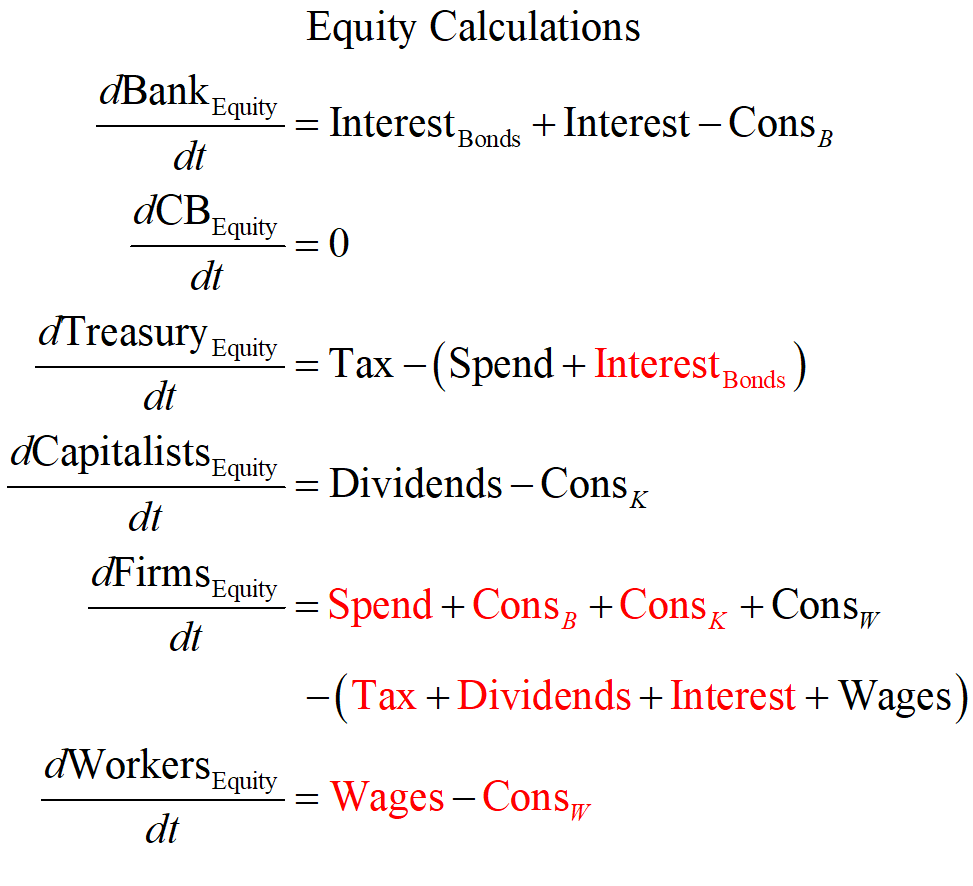

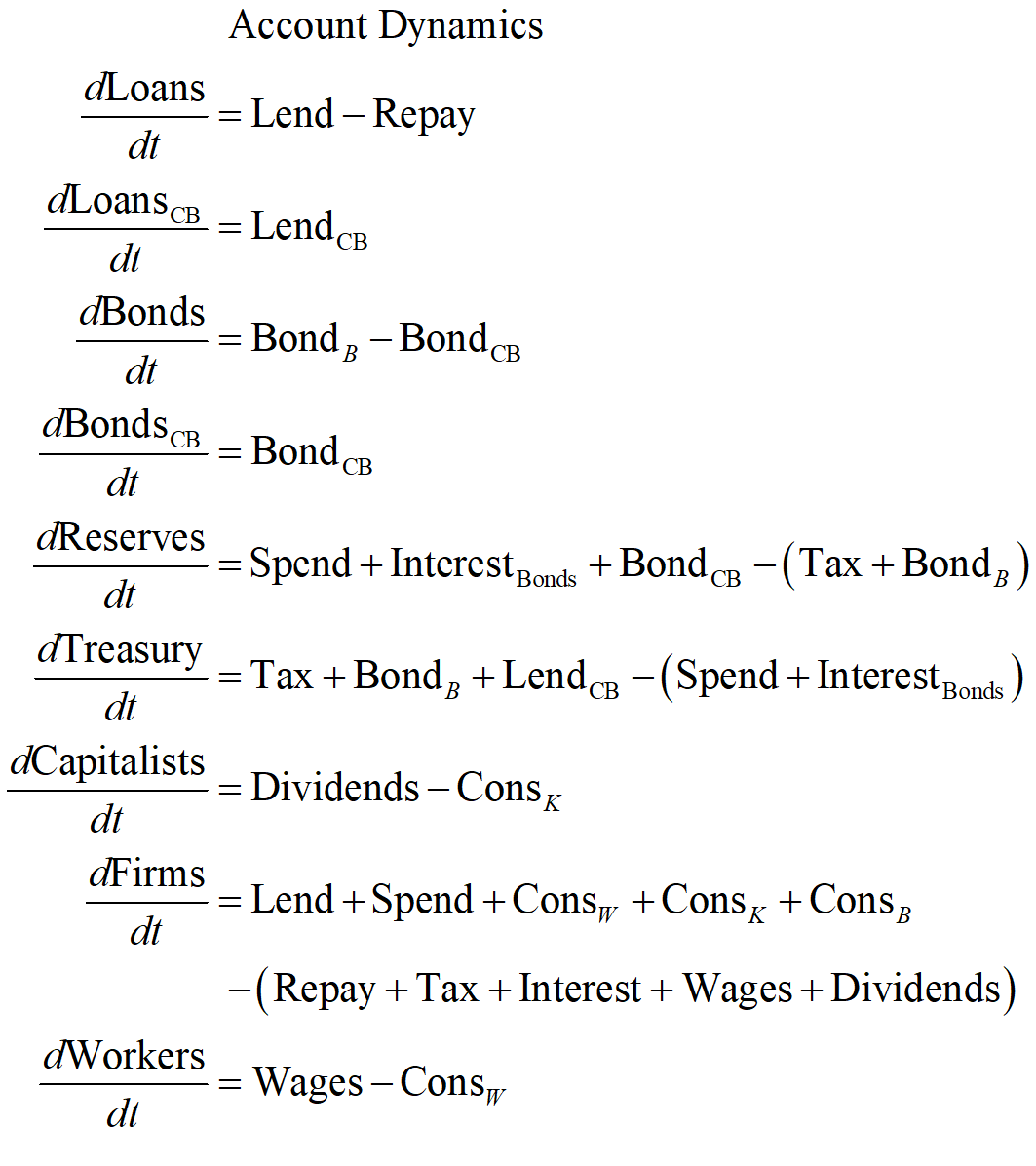

Banks themselves developed out of the double-entry bookkeeping system designed by accountants to keep track of financial commitments (Gleeson-White 2011): all transactions are recorded twice, once from the source account and once in the destination account. Accounts are classified as Assets, Liabilities, or Equity, following the rule that Assets minus Liabilities equals Equity. Minsky employs these accounting rules to build macroeconomic models based on monetary transactions, using double-entry bookkeeping tables we call “Godley Tables”.

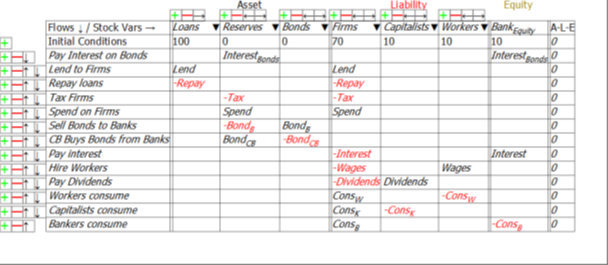

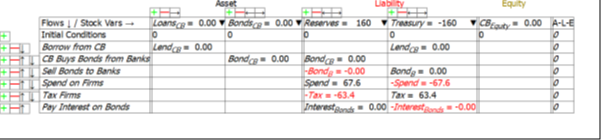

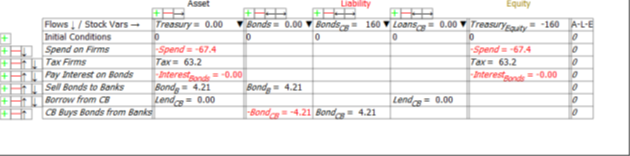

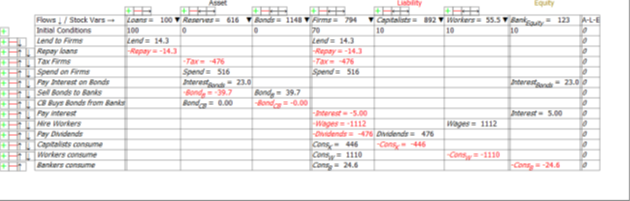

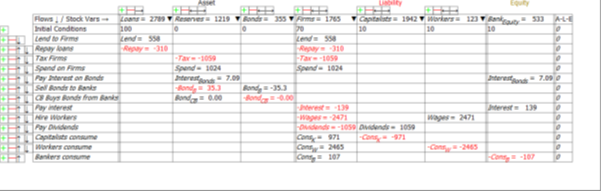

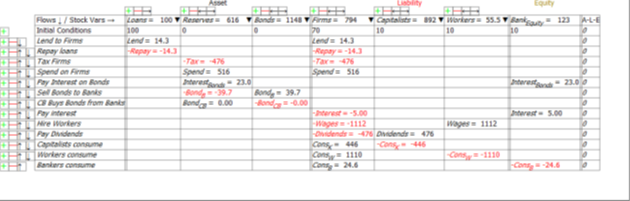

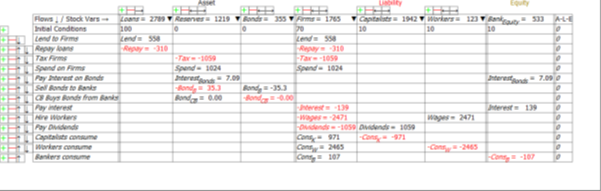

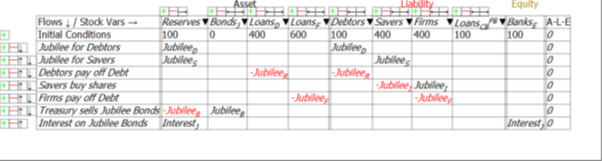

This method of modelling money is both remarkably simple and remarkably powerful. It can easily demonstrate the key differences between Loanable Funds and a realistic model of what banks actually do, which I call “Bank Originated Money and Debt” (BOMD)—see Figure 2.

Figure 2: Loanable Funds versus Bank Originated Money and Debt

The first table in Figure 2 shows the basics of the Loanable Funds model of banking, in which banks do not create debt themselves, but facilitate lending from one group of non-Bank entities (“Savers”) to another (“Borrowers”). The key features of this false, Neoclassical model of banking are:

- Money is the sum of the amounts in the Liability and Equity accounts of the banking sector;

- Banks don’t lend money. Instead, they facilitate loans between some of their customers (“Savers”) and others (“Borrowers”);

- The lending and repayment action occurs on the Liabilities side of the banking sector’s ledger—nothing happens on the Asset side;

- Because Loans are neither an Asset nor a Liability of the Banks, Loans don’t appear on the Banking Sector’s ledger;

- Reserves are needed to back the deposits made by savers, borrowers, and the banking sector itself;

- Interest income on loans accrues to Savers rather than to the Banks;

- Banks earn income not from interest on loans, but from charging “intermediation fees” to borrowers or savers; and

- Finally, and most importantly for the significance of banking in macroeconomics, money is neither created by lending, nor destroyed by repayment. Instead the existing stock of money in this model is shuffled between the bank accounts of Savers and Borrowers.

The second table in Figure 2 shows the basics of actual lending, with the differences between real-world lending and the Loanable Funds model highlighted in italics:

- Money is the sum of the amounts in the Liability and Equity accounts of the banking sector;

- Banks do lend money;

- The lending and repayment action occurs on both the Assets and the Liabilities side of the banking sector’s ledger. Lending increases Loans, which are an Asset of the banking sector, and it also increases the deposit accounts of Borrowers—which are Liabilities of the banking sector. Repayment reduces the banking sector’s Assets (Loans) and Liabilities (Deposit accounts);

- Loans are Assets of the banking sector (Reserves don’t appear in this simplified model, because they’re not involved in lending—a topic I’ll return to below);

- Interest income accrues to the banking sector: one of its Liabilities (the deposit accounts of Borrowers) falls and its Equity rises; and

- Finally, and most importantly for the significance of banking in macroeconomics, money is created by lending and destroyed by repayment.

The only thing these two models agree upon is the definition of money. It would be astounding if they didn’t have different predictions for the impact of bank lending on the economy.

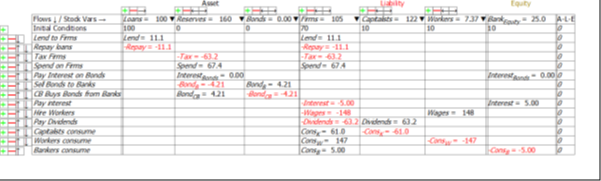

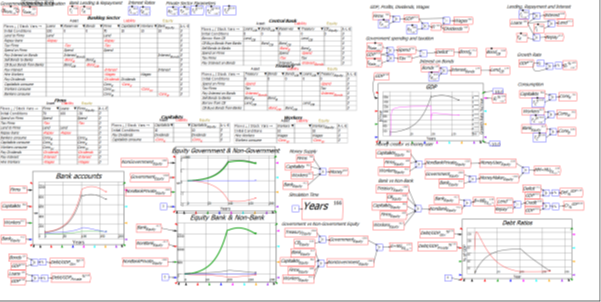

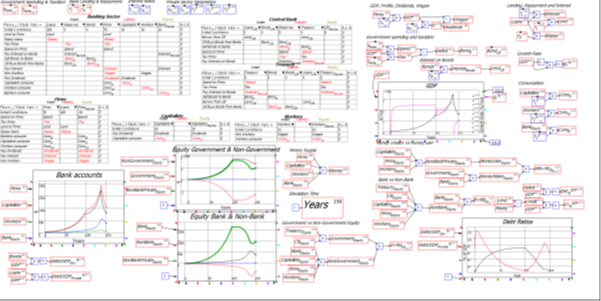

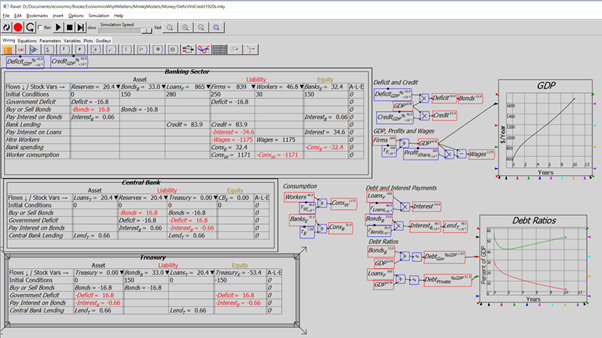

Figure 3: A quick primer on Minsky

Figure 3: A quick primer on Minsky

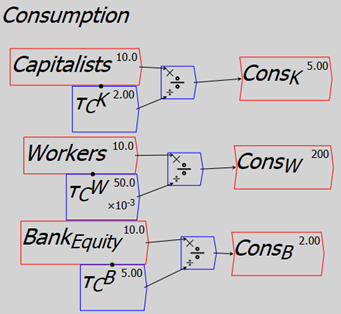

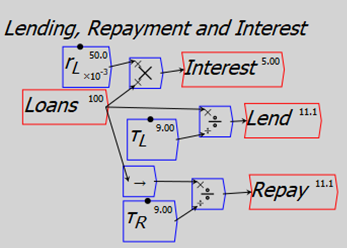

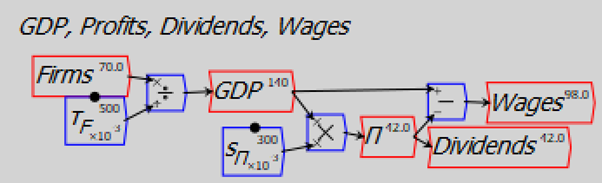

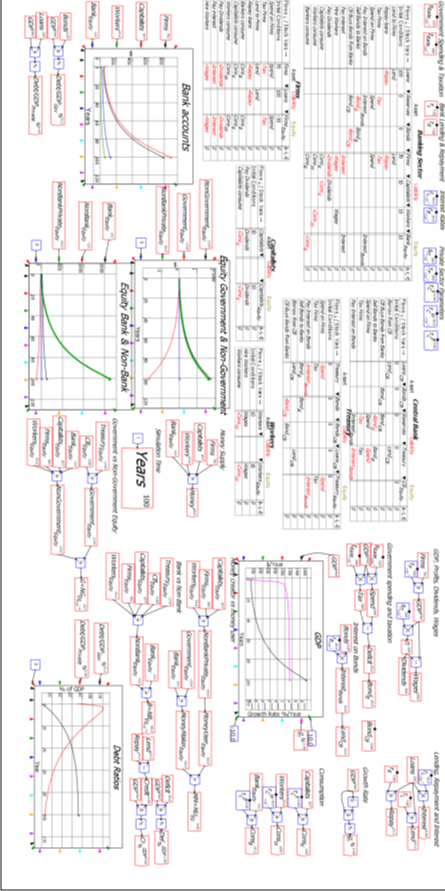

Using Minsky, it’s easy to show how profoundly different these predictions are. Figure 4 shows a model of Loanable Funds in which:

- Capitalists lend to Firms;

- Firms hire Workers, pay dividends and interest to Capitalists, and intermediation fees to the Banks; and

- Capitalists, Workers and Bankers buy the output of the Firm sector.

The rates of lending and repayment have been varied during the simulation, so that credit—the difference between new loans and the repayment of old loans—is positive for a while, then negative, then positive again, and finally neutral. This results in large changes in debt, from 50% of GDP to over 150%, and then back again. The changes in the level of debt have some impact on GDP and incomes, but they move in the opposite direction: GDP falls with rising private debt, and rises with falling private debt. But there is no impact of changing levels of private debt upon the total money supply: this remains fixed at $200 billion throughout the simulation.

Figure 4: A Loanable Funds model in which capitalists lend to firms

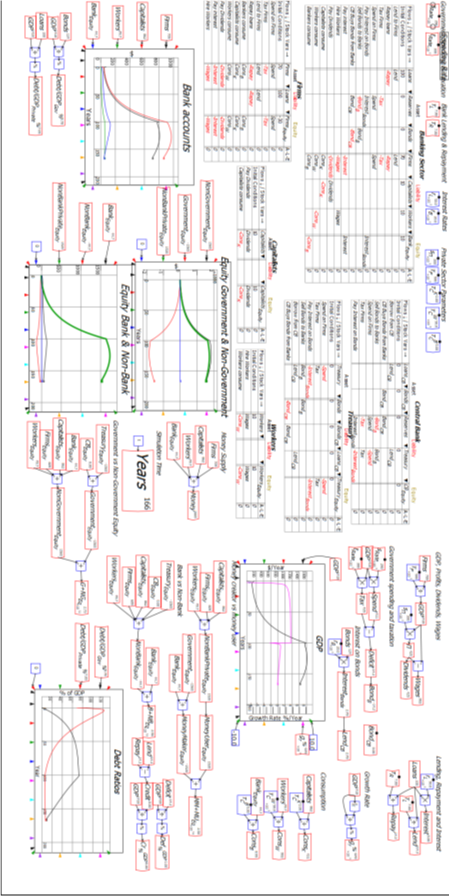

This model can be easily converted into the real-world model of “Bank-Originated-Money-and-Debt” (BOMD), simply by showing Loans as an Asset of the Banks, rather than the Capitalists. Interest payments are shifted from Capitalists to Banks as well, and the superfluous Fee to banks is deleted. The result is a dramatically different vision of how a monetary economy works. Most importantly, the rising level of debt causes a rising level of money: as debt rises and falls, so does the money supply. Also, rather than the debt to GDP ratio and GDP moving in opposite directions, they move in the same direction: a rising debt to GDP ratio causes a rising level of income, and falling debt causes falling income.

Figure 5: A Bank Originated Money and Debt model where banks lend to firms

These simulations show that the real world of “Bank Originated Money and Debt” is vastly different to the Neoclassical fantasy model of Loanable Funds. But why is it so? How does credit add to aggregate demand?

-

The logic of credit’s role in aggregate demand

One of the guiding principles of macroeconomics is that one person’s expenditure is another person’s income. Thus, if you spend $250 a year at your local Pizza shop, the sum of your expenditure on Pizza (minus $250 from your bank account) and the Pizza shop’s income from you (plus $250 into the Pizza shop’s bank account) is zero. This is because what is an expenditure to you (buying the pizza) is an income to the recipient (selling the pizza). Expenditure and income are two perspectives on precisely the same transaction.

The same principle applies at the macroeconomic level: expenditure IS income.

We can use this to construct a table showing expenditure and income for any economy, where the rule is that each row shows expenditure by one entity on all other entities in the economy, and that row must sum to zero. Let’s divide the economy into three sectors—say, Manufacturing, Services, and Households, and use capital letters to indicate spending per year by each sector on the other two: so Manufacturing spends A dollars per year on Services, and $B per year on Households. Table 1 shows this view of the economy—which I have named a Moore Table after the Post Keynesian economist Basil Moore (Moore 1979). Notice that each row sums to zero, that each column can differ from zero, and that the whole table sums to zero.

Table 1: A Moore Table showing expenditure IS income for a 3-sector economy

We can now classify parts of the table as aggregate expenditure and aggregate income. The negative of the sum of the diagonal elements is aggregate expenditure. The sum of the off-diagonal elements is aggregate income. They are necessarily identical.

We can now classify parts of the table as aggregate expenditure and aggregate income. The negative of the sum of the diagonal elements is aggregate expenditure. The sum of the off-diagonal elements is aggregate income. They are necessarily identical.

Table 1 is a monetary economy without lending. We can modify it to show the Neoclassical vision of lending, Loanable Funds, by imagining that one sector (say, Services) lends Credit dollars per year to another sector (say, Households), and then Households use this borrowed money to buy more goods from Manufacturing. However, the lending by Services lending comes at the expense of the Service Sector’s spending on Manufacturing (you can’t spend money you’ve lent to someone else). So Services spends (D-Credit) dollar per year on Manufacturing, whereas Households spend (B+Credit) dollars per year on Manufacturing. Lending from the Services Sector to the Household Sector is neither Expenditure nor Income, so the transfer of money can’t be shown horizontally: it is instead shown as a transfer across the diagonal, reducing the expenditure of the lender (Services) and increasing the spending of the borrower (Households). Households pays Interest dollars per year on its outstanding debt to Services, and since this is both an expenditure and an income, it is shown horizontally.

Table 2: The Moore Table for Loanable Funds

When you add up expenditure and income in this table, Credit cancels out: for every positive entry for Credit in either Aggregate Demand (the negative of the sum of the diagonal cells) or Aggregate Income (the sum of the off-diagonal cells), there’s an offsetting negative entry that cancels it out. The only effect of lending on this model of the economy is that Interest payments turn up as part of both expenditure and income:

When you add up expenditure and income in this table, Credit cancels out: for every positive entry for Credit in either Aggregate Demand (the negative of the sum of the diagonal cells) or Aggregate Income (the sum of the off-diagonal cells), there’s an offsetting negative entry that cancels it out. The only effect of lending on this model of the economy is that Interest payments turn up as part of both expenditure and income:

Table 3 shows the real-world situation of “Bank Originated Money and Debt”. It’s more complicated than the other tables, because we have to add the Banking Sector to the model, and we have to include the Banking Sector’s Assets—where Credit appears as an increase in the Banking Sector’s loans to the Household Sector—as well as its Liabilities and its Equity. Table 3 explicitly shows all spending as passing through the Liabilities (Deposit accounts) and Equity sides of the banking sector’s accounts. The Household Sector’s expenditure on Manufacturing includes Credit, as in Loanable Funds, but this credit-financed spending does not come at the expense of any other sector’s expenditure: instead, it comes from the creation of new money via the expansion of the Banking Sector’s Liabilities and Assets.

Table 3: The Moore Table for Bank Originated Money and Debt

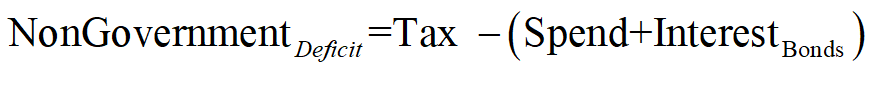

The key outcome is that Credit does not cancel out, as it does in Loanable Funds: there is a single entry for Credit in Aggregate Expenditure—it finances part of the Household Sector’s purchases from the Manufacturing Sector—and a single entry in Aggregate Income—where it is part of the Manufacturing Sector’s income:

The key outcome is that Credit does not cancel out, as it does in Loanable Funds: there is a single entry for Credit in Aggregate Expenditure—it finances part of the Household Sector’s purchases from the Manufacturing Sector—and a single entry in Aggregate Income—where it is part of the Manufacturing Sector’s income:

Consequently, in the model shown in Table 3—and in the real world—credit is a substantial source of both Aggregate Demand and Aggregate Income. This is the logical explanation of the difference in behavior between the “Loanable Funds” model shown in Figure 4 and the BOMD model shown in Figure 5. It is also the explanation for the real-world phenomena of debt-deflationary crises like the Great Recession, the Great Depression, and the Panic of 1837. Neoclassical economics, by ignoring banks, debt and money in its macroeconomic models, is ignoring the main factors that drive economic performance, and also cause economic crises.

-

Negative credit, economic crises, and economic policy

Neoclassical economists appropriated Nassim Taleb’s phrase “The Black Swan” (Taleb 2010) to assert that the Great Recession was impossible to predict, because crises like it are so rare, and because their causes are fundamentally random. Called “exogenous shocks” by Neoclassicals, random events are the only factors that cause Neoclassical models of the economy to deviate from equilibrium. So, “exogenous shocks” must have caused the Great Recession. The Boston College Economics Professor Peter Ireland put it this way:

In terms of its macroeconomics, was the Great Recession of 2007–09 really that different from what came before? The results derived here from estimating and simulating a New Keynesian model provide the answer: partly yes and partly no.

These results suggest that largely, the pattern of exogenous demand and supply disturbances that caused the Great Moderation to end and the Great Recession to begin was quite similar to the patterns generating each of the two previous downturns in 1990–91 and 2001. Compared to those from previous episodes, however, the series of adverse shocks hitting the U.S. economy most recently lasted longer and became more intense, contributing both to the exceptional length and severity of the Great Recession. (Ireland 2011, p. 51).

The policy prescription from this analysis is … to do nothing at all, beyond the Boy Scout motto of “be prepared”. From the perspective of the Neoclassical paradigm, crises like the Great Recession can’t be anticipated, let alone made less likely by economic policy. We can only deal with their consequences after they happen.

This is akin to Aristotle’s theory of comets (which was preserved in Ptolemaic astronomy) that comets were unpredictable, because they were atmospheric phenomena (Aristotle and (translator) 350 BCE [1952], Part 7). The Copernican scientific revolution, which overthrew this worldview, showed that comets were inherently predictable, as they are celestial objects orbiting the Sun.

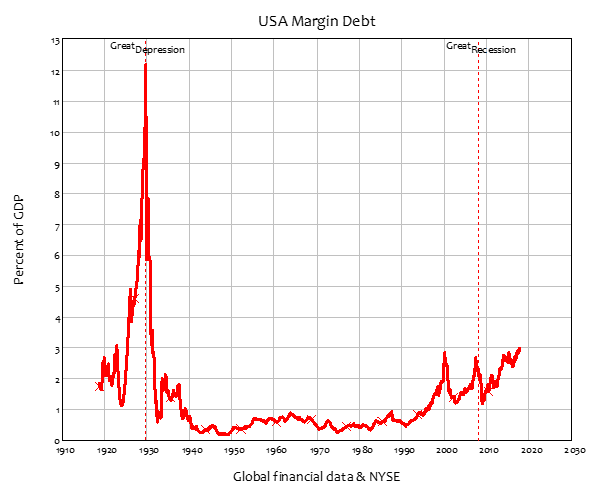

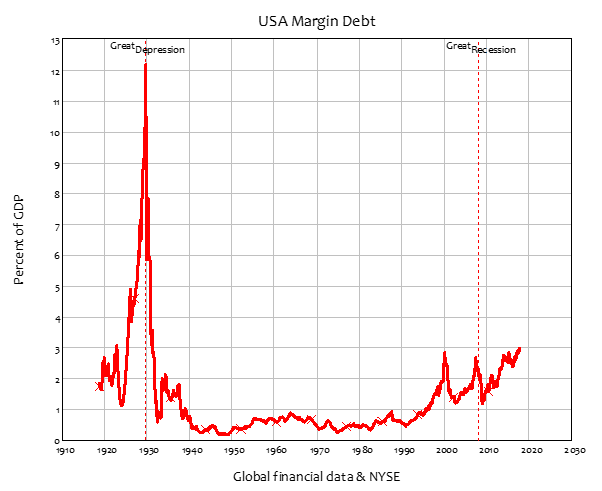

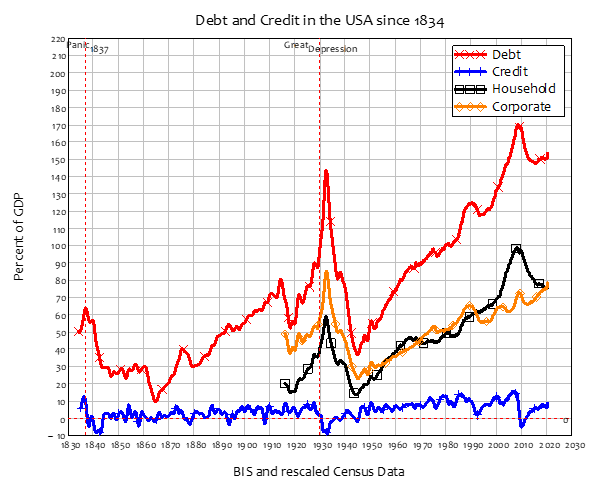

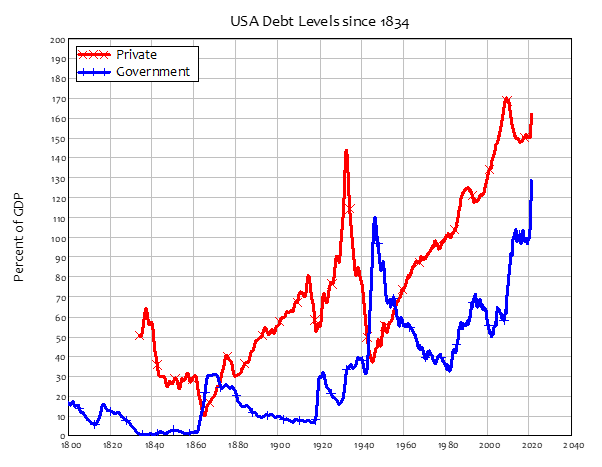

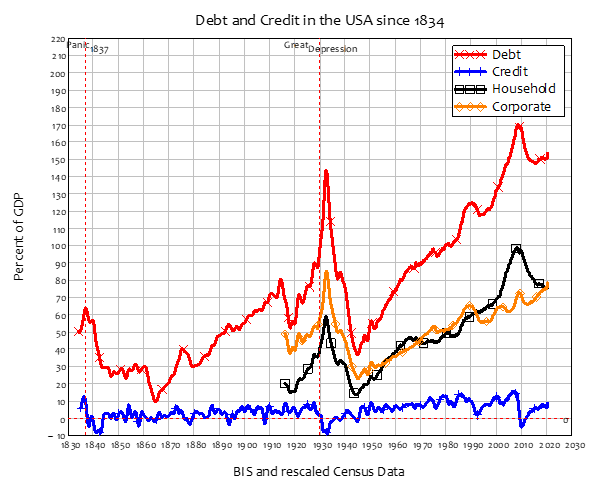

Similarly, the “unpredictability” of crises like the Great Recession is a product of the Neoclassical paradigm’s false Loanable Funds model of money. The correct Bank Originated Money and Debt model shows that crises are caused by credit turning negative (Vague 2019), and that most recessions are caused by credit declining, but not quite going negative. This causal relationship between credit (which is identical in magnitude to the annual change in private debt) and economic performance endows capitalist economies with a tendency to accumulate higher and higher levels of private debt. This phenomenon is most evident in that most capitalist of economies, the United States of America—see Figure 6.

Figure 6: Private Debt and Credit in the USA since 1834

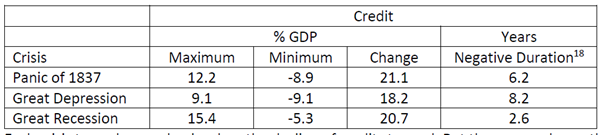

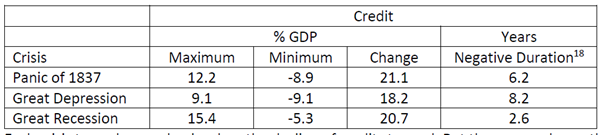

This chart identifies America’s three great economic crises: the Great Recession, the Great Depression, and the “Panic of 1837”. What, you haven’t heard of the “Panic of 1837”? Neither had I, until I produced this chart (Census 1949, Census 1975), but after doing so, I found it was described at the time as “an economic crisis so extreme as to erase all memories of previous financial disorders” (Roberts 2012, p. 24). In each of these crises, credit plunged from a historically high level, turned negative, and remained negative for a substantial period—see Table 4.

Table 4: Magnitude of Credit and duration of negative credit in the USA’s major economic crises

Each crisis turned around only when the decline of credit stopped. But the renewed growth engendered by rising credit came at the expense of a rising private debt to GDP ratio, with this rise terminated either by another crisis, or by wars that drove the private debt ratio down dramatically because of the “War Economy” boost to GDP: nominal GDP growth reached 32% p.a. during the US Civil War in (1861-65), 29% during WWI (1914-1918), and 29% again during WWII (1939-45), far exceeding the maximum growth rate of credit during those periods (0.2% of GDP p.a., 8.6% and 4.5% respectively).

Each crisis turned around only when the decline of credit stopped. But the renewed growth engendered by rising credit came at the expense of a rising private debt to GDP ratio, with this rise terminated either by another crisis, or by wars that drove the private debt ratio down dramatically because of the “War Economy” boost to GDP: nominal GDP growth reached 32% p.a. during the US Civil War in (1861-65), 29% during WWI (1914-1918), and 29% again during WWII (1939-45), far exceeding the maximum growth rate of credit during those periods (0.2% of GDP p.a., 8.6% and 4.5% respectively).

This is no way to run an economy, but it is what we are stuck with while economic policy is dominated by a theory of economics that ignores banks, private debt, money, and credit. However, with a new, monetary paradigm, several things become evident: we should stop the level of private debt from getting too high, and credit-based demand should not be allowed to become too large a component of aggregate demand. But how could we do that?

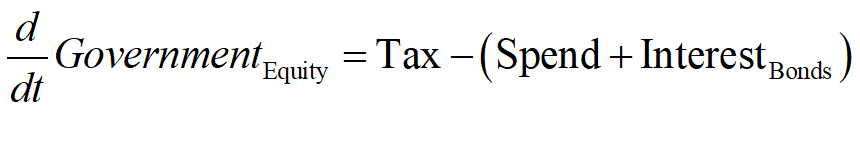

It’s time to take a monetary look at the other type of debt: government debt.

-

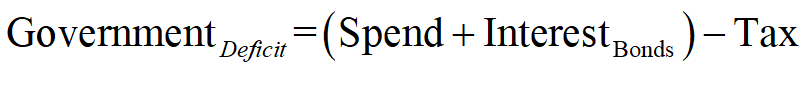

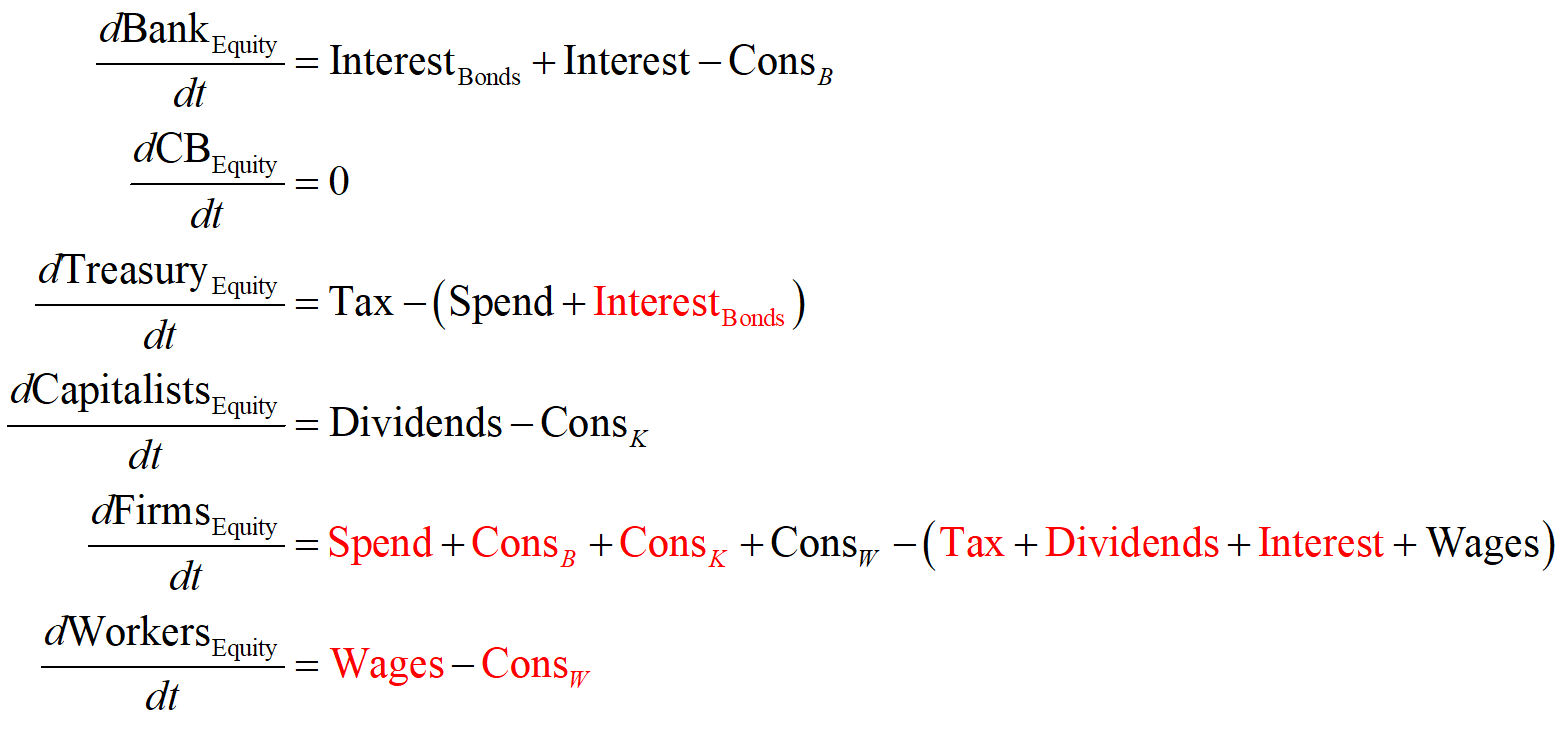

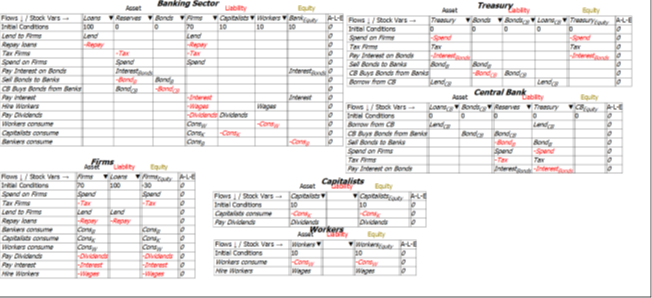

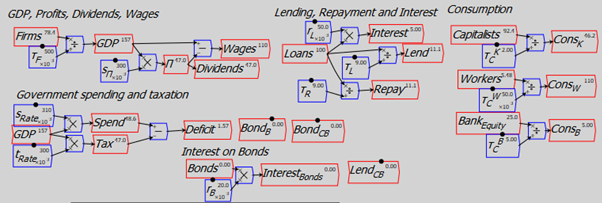

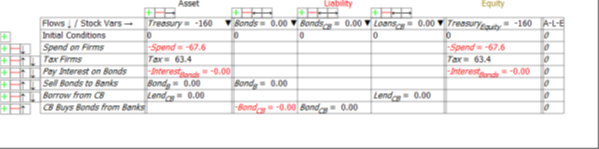

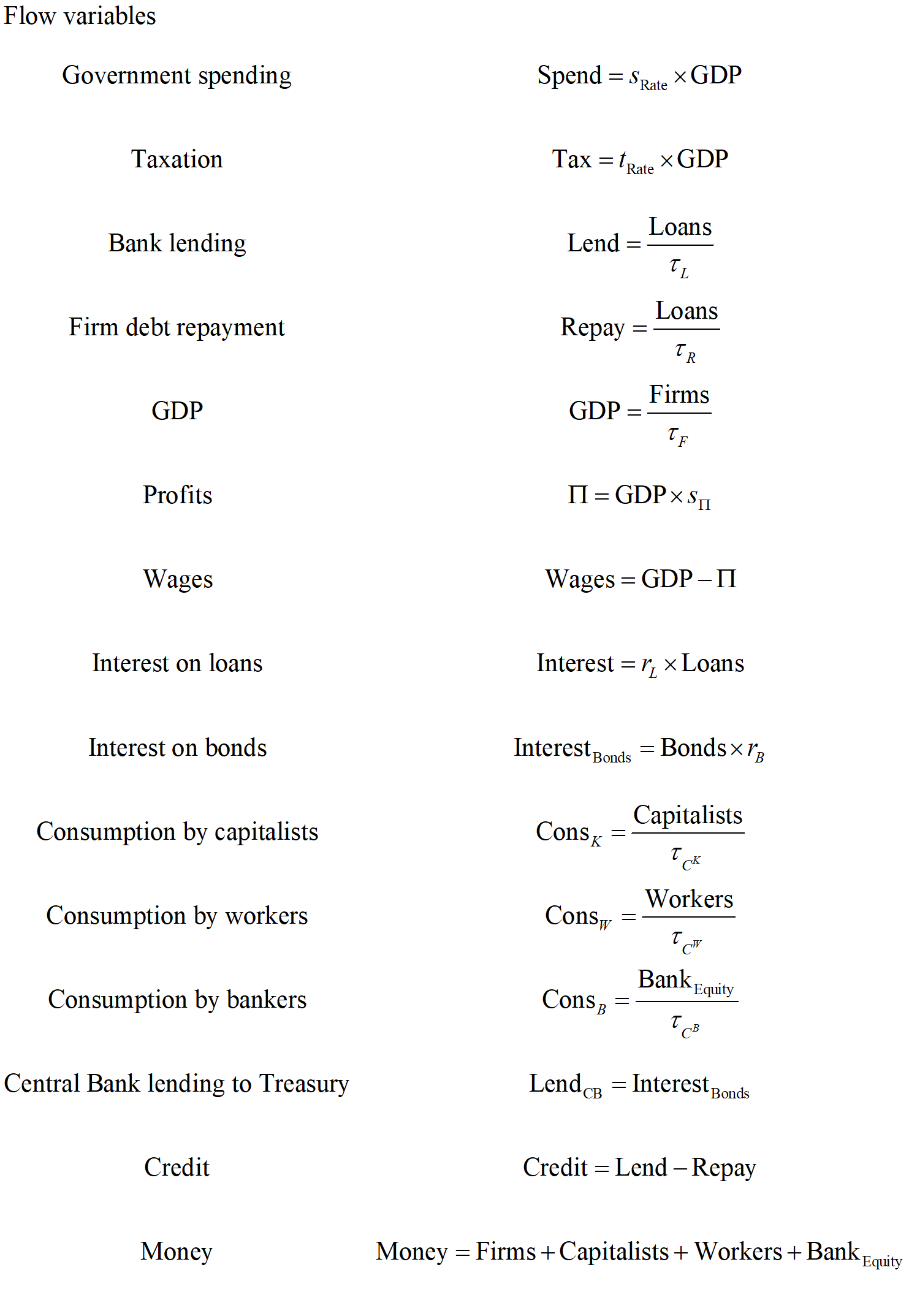

Modelling Fiat Money in Minsky

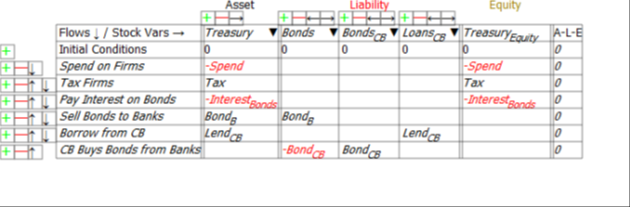

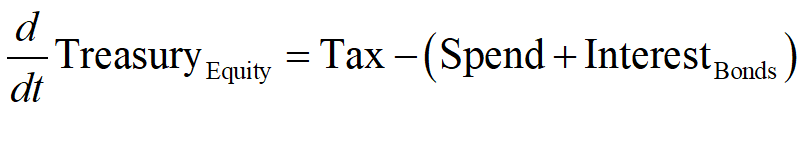

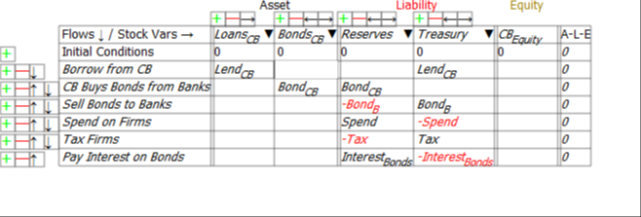

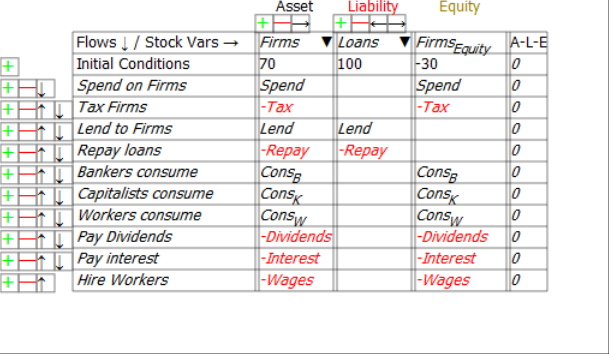

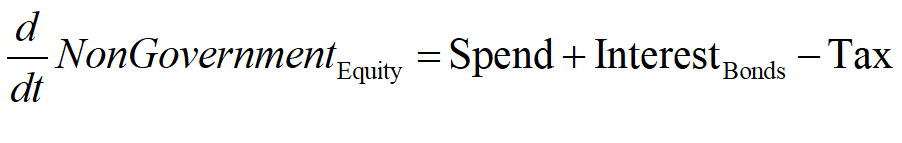

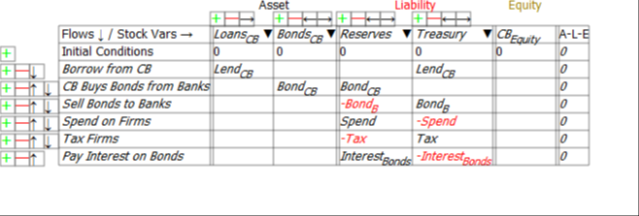

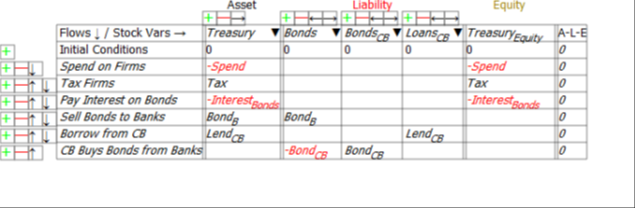

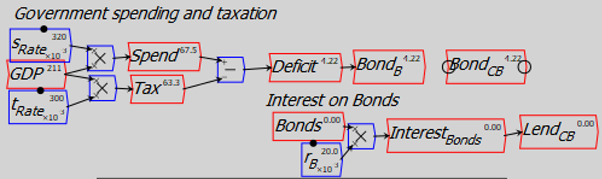

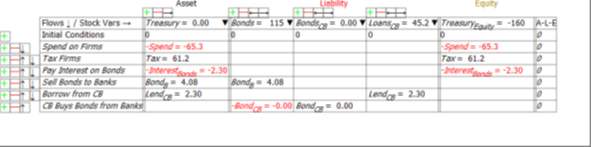

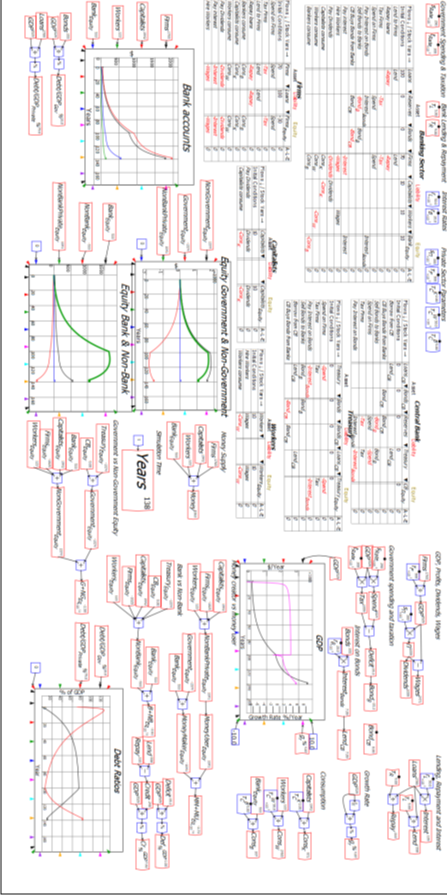

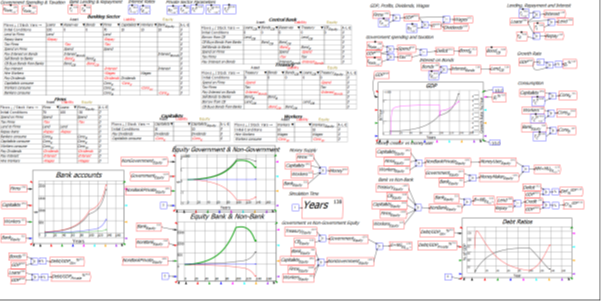

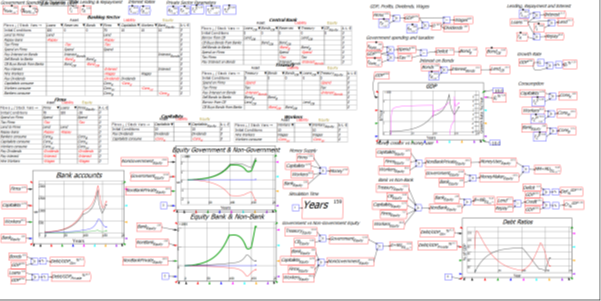

Minsky can model government money creation—fiat money—just as easily as it can credit money. Figure 7 shows the basic monetary operations of a government involve spending on the public (either via purchases of goods or direct income support), taxing the public, selling bonds to the financial sector to cover any gap between spending and taxation, paying interest on those bonds, the Central Bank buying some of those bonds off financial entities in “Open Market Operations”, and Banks selling Treasury Bonds to the non-bank private sector.

Figure 7: The fundamental monetary operations of the government

Though a complete picture requires looking at the Central Bank and Treasury balance sheets as well (see Figure 8), several facts about government financing can be deduced from it that are the opposite of conventional beliefs—conventional beliefs which originate with Neoclassical economists, and are promulgated in their textbooks, such as Mankiw’s Macroeconomics (Mankiw 2016).

Firstly, Neoclassicals allege that the government has to borrow from the public to finance any excess of government spending over taxation:

When a government spends more than it collects in taxes, it has a budget deficit, which it finances by borrowing from the private sector or from foreign governments. The accumulation of past borrowing is the government debt. (Mankiw 2016, p. 555. Emphasis added)

Secondly, they claim that this debt burdens future generations:

“government borrowing reduces national saving and crowds out capital accumulation… Many economists have criticized this increase in government debt as imposing an unjustifiable burden on future generations” (Mankiw 2016, pp. 556-57)

Figure 7 shows that the first conventional (Neoclassical) belief is the exact opposite of the truth. Firstly, when government spending exceeds taxation (when Spend is greater than Tax in Figure 7) then the amount of money in the private sector increases by the same amount: government spending increases the Deposits of the non-bank, non-government sector of the economy. This means that the Banking Sector’s liabilities to the Non-Bank Private Sector rise, and this is matched by an identical increase in the Banking Sector’s assets of Reserves. Since both the Assets and the Liabilities of the Banking Sector have risen, and money is the sum of the Liabilities and Equity of the Banking Sector, then the deficit has created money (Kelton 2020). The government doesn’t need to borrow what it has already created.

But what about the sale of Treasury Bonds to the Banking Sector? Is that borrowing? Technically yes, because Treasury Bonds are a debt of the government to the holder of those bonds. But where does the Banking Sector get the money it uses to buy these bonds? The real-world process is more complicated, but fundamentally, as well as creating additional money (when Spend is greater than Tax in Figure 7) the deficit creates an identical amount of Reserves. Reserves are an Asset of the Banking Sector that normally earns no interest. So, when the government then offers to sell Treasury Bonds equal to the size of the deficit, it is presenting the Banking Sector with an offer to convert non-income-earning Reserves into income-earning Treasury Bonds. This is why every sale of Treasury Bonds in history has been not merely successful, but oversubscribed: an auction of Treasury Bonds is an offer to convert a non-income-earning gift (the additional Reserves created by the deficit) into an income-earning one (Treasury Bonds). Of course, the Banking Sector takes advantage of that offer.

What would happen if the Treasury didn’t sell the bonds—so that all the bond-related flows in Figure 7 would not exist? Money creation would still occur, because, in that case, the only entries in the Liabilities & Equity side of the Banking Sector’s accounts would be Spend minus Tax: the deficit itself creates money, regardless of whether or not bonds are sold to cover the deficit. The consequences of not selling bonds therefore lies elsewhere in the financial system.

The Treasury’s balance sheet in Figure 8 (the 3rd table in the Figure) shows what these are. The first column is the Treasury’s “deposit account” at the Central Bank. Without the bond sales, the only guaranteed flows into and out of that account are Tax minus Spend—the same terms as for the creation of money, but with the opposite sign. Therefore, the impact of the government not selling bonds equal to the deficit each year would be that, with sustained deficits over time, the Treasury’s deposit account at the Central Bank would go negative—it would turn into an overdraft account.

For a private entity, an overdraft at a private bank means a much higher interest rate than on a standard loan on the negative balance in its deposit account, limits on how high the overdraft can be, other possibly punitive measures, and the prospect, if the overdraft gets too large, of bankruptcy. But for the Treasury, there are no such consequences, since the Treasury is the effective owner of the Central Bank. In some countries, the Treasury is required by law to pay interest to the Central Bank on any loans, including overdrafts, but in all countries, the profits of the Central Bank are remitted to the Treasury—so in effect the Treasury pays zero interest on its “debt” to the Central Bank. There are effectively no consequences for the Treasury from having an overdraft at the Central Bank.

All bond sales do is enable the Treasury to avoid an overdraft, by keeping its Central Bank account positive (or at least non-negative). Most governments have passed laws requiring its Treasury to not be in overdraft to its Central Bank—though these laws were waived by some countries during the Covid-19 crisis. New laws, based on a realistic appreciation of the role of government money creation in a well-functioning economy, could enable the Treasury to always run an overdraft—or let it run up a debt to the Central Bank—obviating the need to sell bonds at all.

What about the interest on Treasury Bonds? That can be paid by the Treasury borrowing from the Central Bank—(the term LendCB in Figure 7)—and thus adding to a loan on which it effectively pays zero interest. This is a case of the government being in debt to itself, and only for the interest it pays on the bonds it has sold.

The interest payments themselves are another way in which the government creates fiat money in the non-Government sector, this time by adding to the equity of the Banking Sector (or whoever the Banking Sector has sold bonds to). Banks would be the first to complain if the government decided to stop issuing bonds, and took away an easy source of bank profits.

Figure 8: The same operations including the perspective of the Central Bank, Treasury and Non-Bank Private Sector

The Central Bank also does not “monetize” the government deficit when it buys Treasury Bonds off the Banking Sector. This common expression is simply wrong, because the deficit is already “monetized”: to labour the point illustrated by the first two rows of Figure 7, the deficit itself creates money when it increases the Liabilities of the Banking Sector (Deposits) and the Assets (Reserves). Central Bank purchases of Treasury Bonds from the Banking Sector undo the effect of the Treasury selling those bonds to the Banking Sector in the first place: they replace income-earning assets in the Banking Sector’s portfolio (Treasury Bonds) with non-income-earning ones (Reserves). The Banks wouldn’t do the trade without making a profit, but the end-result is they end up with a lower income stream, since they no longer get the interest Treasury pays on those bonds. Far from “monetizing” the deficit, Central Bank bond purchases reduce the amount of money created by the government, since they reduce the amount of interest paid to the Banking Sector.

The only use of Bonds that affects the money supply is the sales of bonds by the Banks to the non-Bank private sector (shown as the second last row in Figure 7), and this destroys money, rather than either creating it, or providing money to the government for it to spend. When Banks sell Treasury Bonds to non-Banks, the deposits of the non-Banks fall, as do the Bank’s own assets of Bonds. This destroys money. Rather than such sales being a source of revenue for the government, they are a source of trading profits for the Banks, and a way to reduce the spending power of the public.

This realistic perspective on government spending upends the conventional wisdom of Neoclassical economics. The government does not “borrow from the private sector” when it runs a deficit. Instead, a deficit creates “debt free” money for the private sector. The deficit increases private savings, rather than reducing them, as Mankiw alleges: the ledger for the Non-Bank Private Sector in Figure 8 shows that the equity of the public (the column PublicEquity in Figure 8) is increased by a deficit (when Spend exceeds Tax) and reduced by a surplus. Deficit thus make it less necessary for households and firms to borrow money from the private banks, while also providing the private banks with a guaranteed source of income, which makes them less likely to want to sell speculative financial assets to the non-bank private sector.

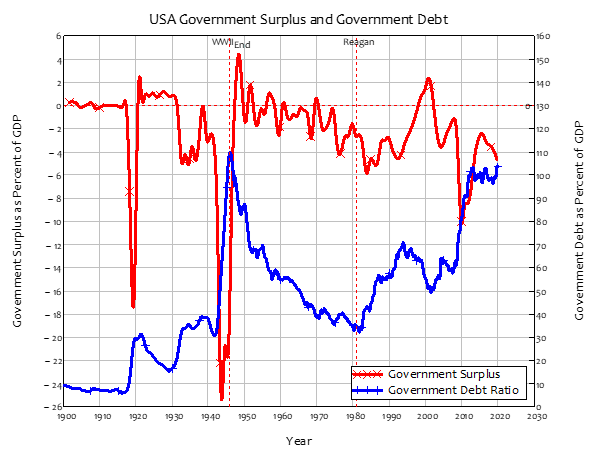

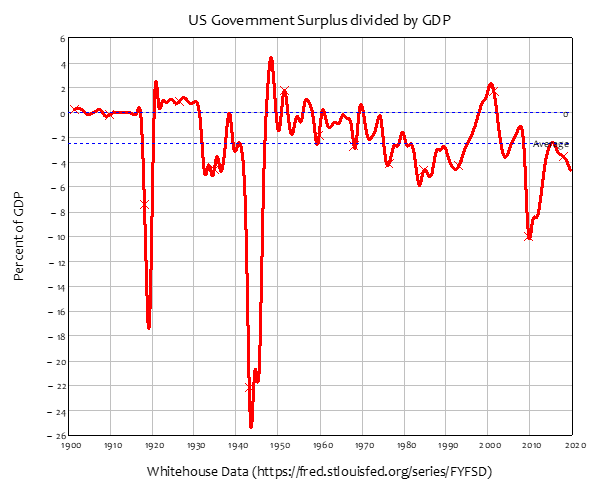

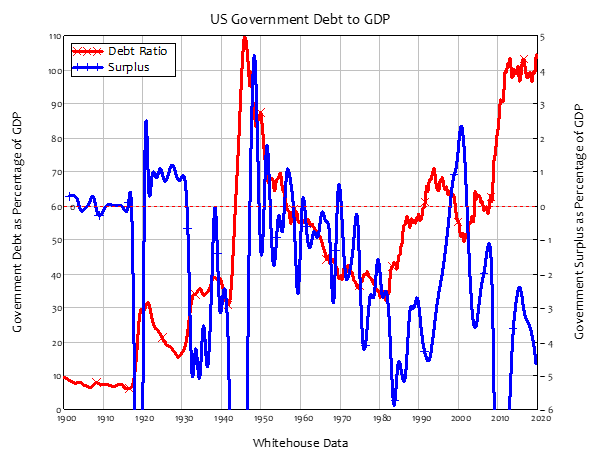

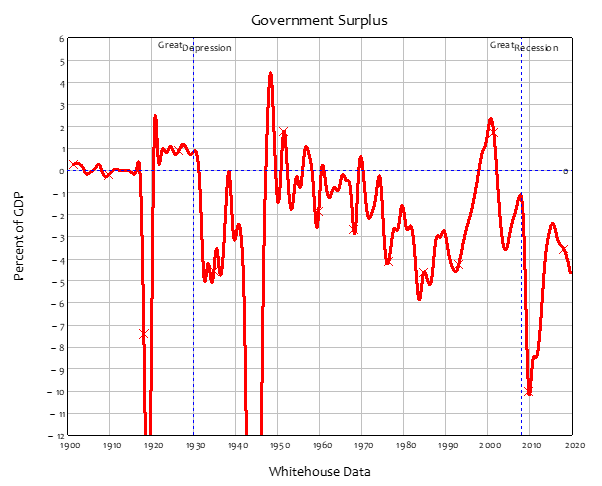

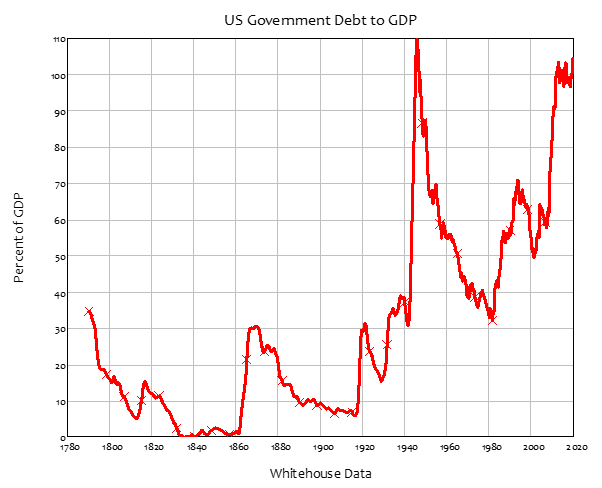

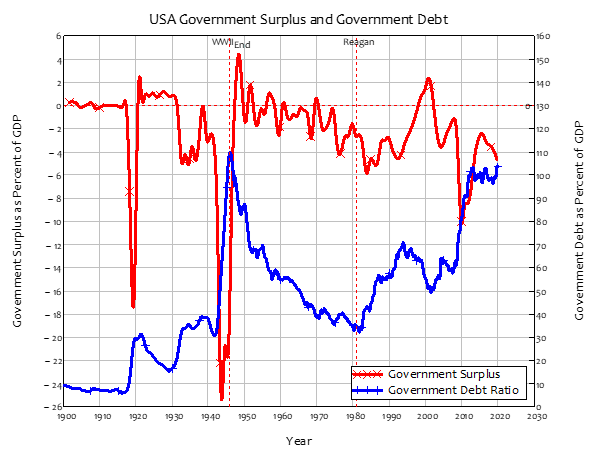

Therefore, far from government deficits “burdening future generations”, they enrich current generations. Any impact on future generations depends on the economic and political consequences of the spending which generates the deficit, and they can be substantially beneficial to the private sector, rather than deleterious. Consider, for example, the enormous deficits of up to 25% of GDP, and the resulting trebling of government debt (from 38% to 109% of GDP) caused by government spending during World War II (see Figure 9). Without that deficit—which, as we have seen above, was funded by fiat money creation, not by borrowing from the public or the banks—and corresponding ones for its allies (the UK’s deficit hit 44% of GDP in 1941), the Axis powers would have won WWII.

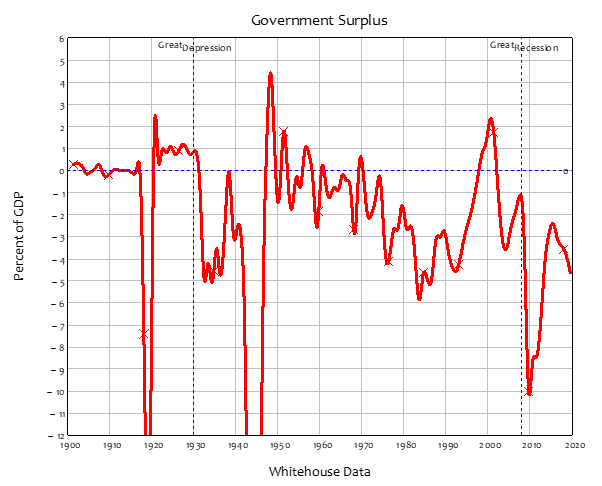

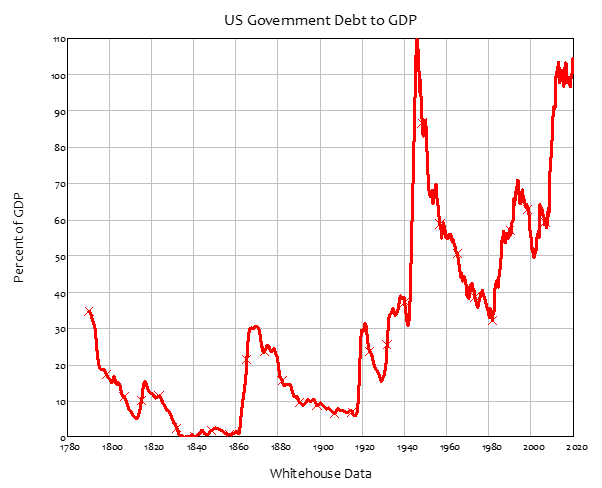

Figure 9: US Government debt and deficits over the past 120 years

Deficits of that scale rapidly increased the government debt to GDP ratio, to 110% of GDP—the highest in America’s history. According to Mankiw and almost all Neoclassical economists, this should have placed an enormous burden on the “future generation” that followed the wartime one. So how did this unfortunate cohort fare?

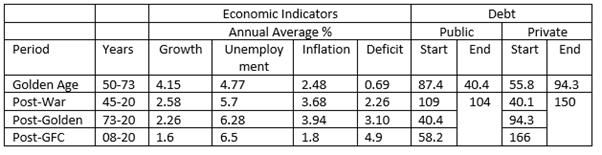

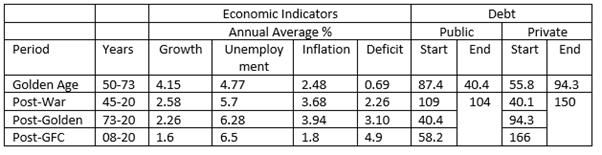

I speak, of course, of the Baby Boomers. Born between 1946 and 1964, they were probably the most privileged generation in human history. Far from suffering pain from having to repay the enormous government debts accumulated during WWII, their time in the sun coincided with the “Golden Age of Capitalism” (Marglin and Schor 1992) between 1950 and 1973. They experienced high growth, low unemployment, low inflation, and—in an apparent paradox—a falling government debt to GDP ratio, while the budget was normally in deficit (see Table 5). If that’s being burdened, then please, bring it on.

Table 5: Economic performance of major periods in post-WWII USA

-

An integrated view of deficits and credit

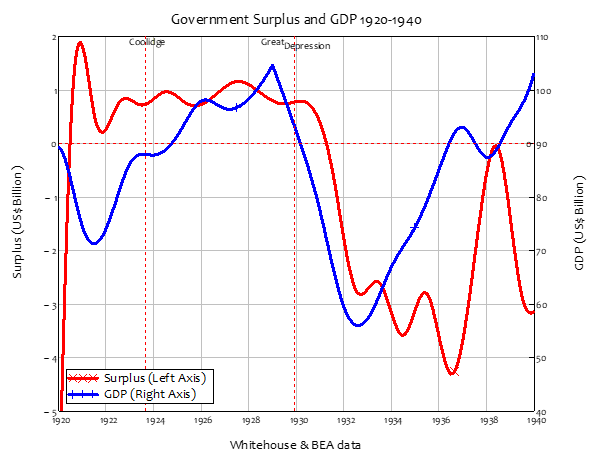

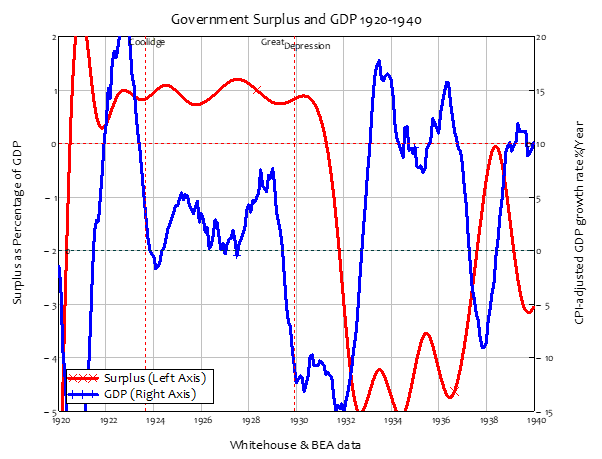

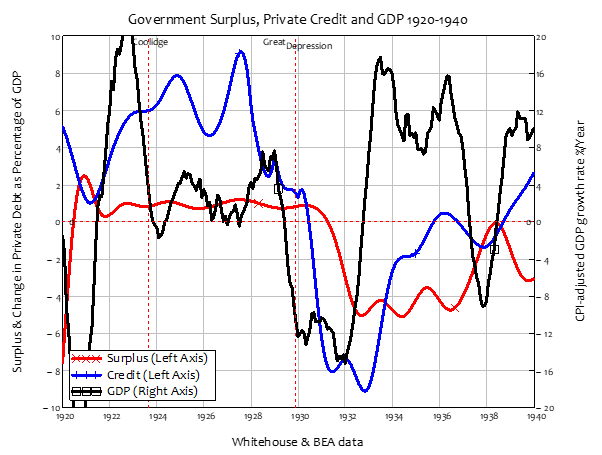

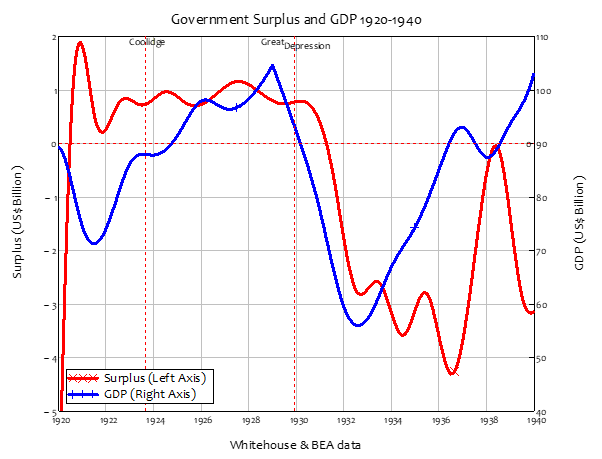

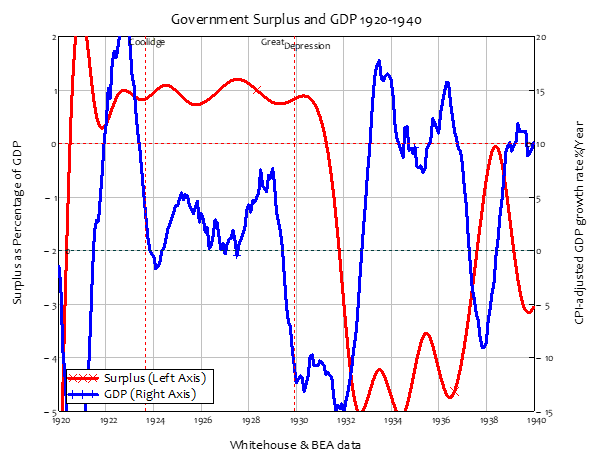

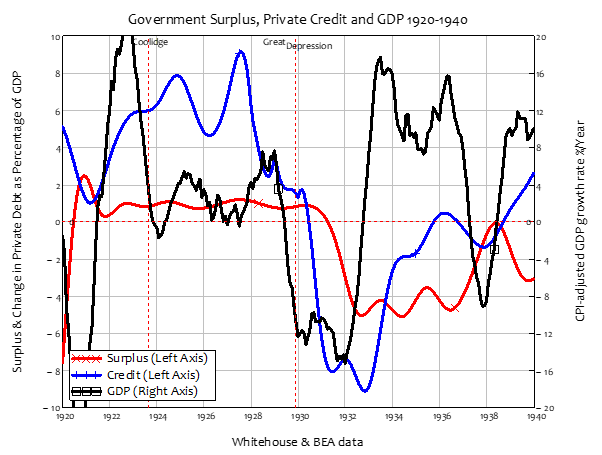

One striking feature of Figure 9 is the rarity of government surpluses, despite the never-ending political rhetoric about achieving them. The only period of sustained surpluses was the 1920s, when the government maintained a surplus of roughly 1% of GDP each year. The “Roaring Twenties”, as the decade became known, was a time of great economic prosperity, and in his 1928 State of the Union Address, then President Calvin Coolidge attributed this success to the government surplus:

No Congress of the United States ever assembled, on surveying the state of the Union, has met with a more pleasing prospect than that which appears at the present time…

a surplus has been produced. One-third of the national debt has been paid… the national income has increased nearly 50 per cent…. That is constructive economy in the highest degree. It is the corner stone of prosperity. It should not fail to be continued. (Coolidge 1928)

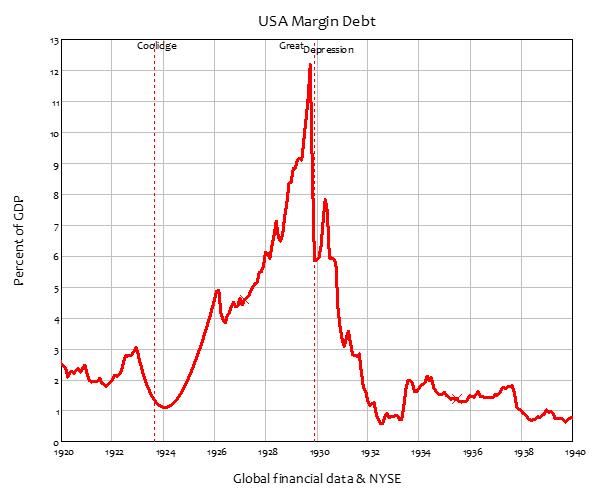

In fact, the surplus was depressing the economy, by taking the equivalent of just under 1% of GDP out of private bank accounts every year. The public responded by borrowing on average 5% of GDP every year, and using this to gamble on financial assets—initially housing in a forgotten but significant housing bubble (Vague 2019), and then in the stock market—in an orgy of debt-fueled speculation. As Coolidge lauded himself for causing government debt to fall from 30% to 15% of GDP, private debt rose from 55% to 100% of GDP—so that for every one dollar of (for the private sector) debt-free fiat money Coolidge removed from the economy, the private sector pumped $3 of debt-based money back in.

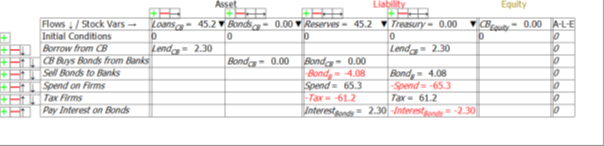

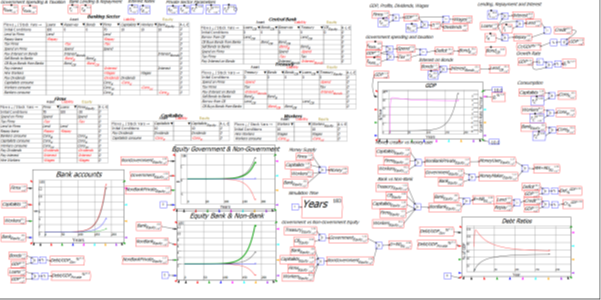

We can avoid Coolidge’s mistake of attributing all of the economy’s performance during the 1920s to the government surplus by building a simple Minsky model with both a government, and a banking sector that lends to the non-bank public: see Figure 10. I did three simulations: one with the Coolidge-era settings of a 1% of GDP government surplus and credit at 5% of GDP; one with a balanced budget and credit at 5%; and one with a 1% of GDP surplus and no credit.

Figure 10: An integrated view of government deficits and private sector credit

The first setting led to the “pleasing prospect” of which Coolidge waxed lyrical. Over a ten-year simulation, GDP rose from $560 billion to $1660, and the government debt ratio fell from 30% of GDP to 2%. But the model economy did better still with a balanced budget. GDP hit $2,000 billion, and the government debt ratio still fell to 7.5%. More tellingly, with the boost from credit removed—with a 1% of GDP surplus and zero credit, and therefore no growth in private debt—the economy slumped. GDP peaked at $750 billion after 3 years and fell thereafter, reaching $700 billion after ten years on a sustained downward trajectory, while the government debt ratio fell less (to 11% of GDP) because GDP was falling as well as government debt.

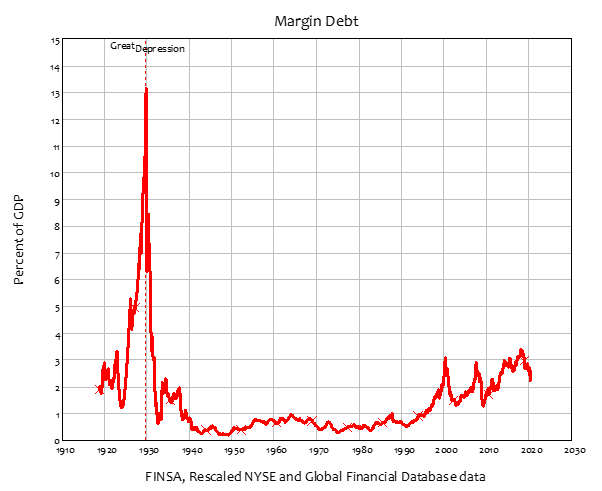

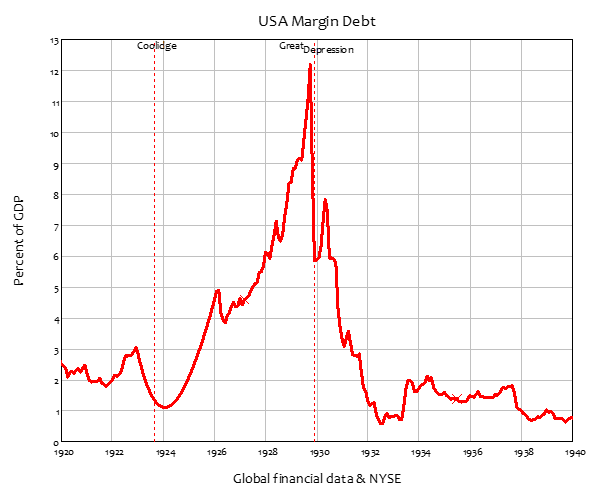

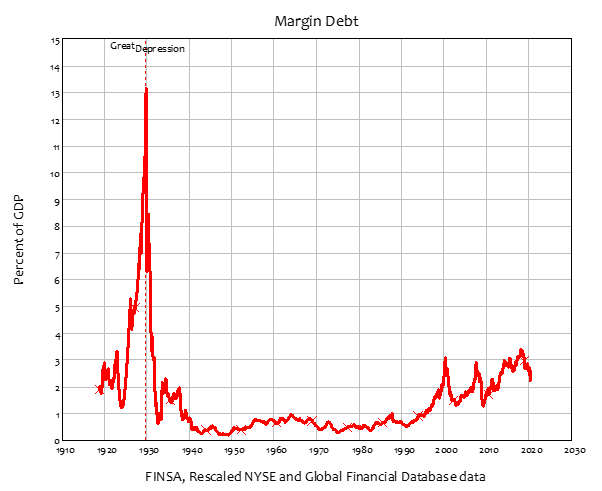

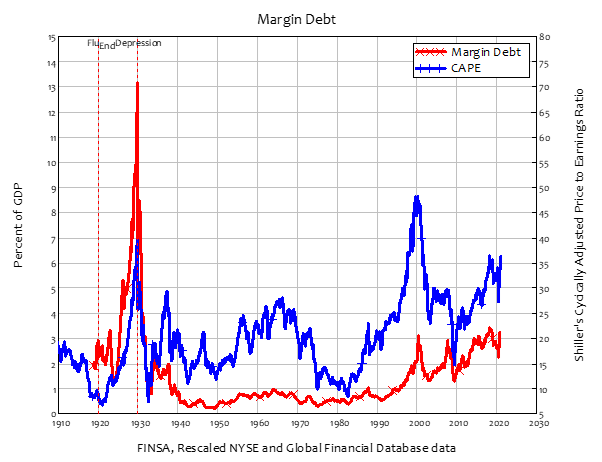

This model actually flatters Coolidge and the 1920s, because borrowing in it boosts GDP via investment by firms and consumption by workers and banks. But during the 1920s, much of the borrowing went into speculation. The most spectacular instance of this was the unprecedented, and unsurpassed, level of margin debt, which rose from 1% of GDP in the early 20s to 13% in October 1929—see Figure 11. This is why the Twenties roared—and largely also why the Thirties wailed.

Figure 11: Margin debt since 1918

Margin debt enabled a speculator to put down a deposit of $1,000 with a stockbroker and borrow $9,000, to buy $10,000 worth of shares with a $10,000 “margin account”. The borrower paid interest on the loan of course, but the leverage meant that, if markets rose 10%, then before expenses, the speculator doubled his money: $10,000 worth of shares became $11,000, doubling the speculator’s net worth from $1,000 to $2,000. There was a catch: if the market fell 10%, then the speculator had to top up the account to keep it at $10,000. This would wipe the speculator’s equity out—from $1,000 to zero (before expenses). If the speculator couldn’t comply with his ready cash, then the stockbroker was entitled by the margin contract to liquidate any of the speculator’s assets: it was an unlimited liability. But most speculators were confident that this would never happen, and over the course of the decade, they were right: while the margin debt to GDP ratio increased 5.5 times between the stock market’s all-time low point in 1921 and October 1929, the stock market itself rose sixfold.

Few were more confident than Professor Irving Fisher, who was his day’s Paul Krugman: a famous mainstream economist (and also inventor) who also wrote a column for the New York Times. He had levered the profits from inventions into the stock market, and became its most prominent cheerleader. On October 16th 1929, Fisher was quoted in the Times as saying at a conference that “Stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau.” He continued:

I do not feel that there will soon, if ever, be a fifty or sixty point break below present levels, such as Mr. Babson has predicted. I expect to see the stock market a good deal higher than it is today within a few months. ( “Fisher sees stocks permanently high“) (Fisher 1929, October 16th, p. 8. Emphasis added)

Just two weeks later, the Dow Jones Industrial Average plunged over 60 points in two days, losing more than 20% of its value. Margin calls wiped out levered speculators like Fisher immediately, and ushered in The Great Depression, which itself did much to cause the rise of fascism and the Second World War.

As awful as those crises were, they had one strong positive economic side-effect, from which the next generation—the Baby Boomers—benefited handsomely. The combination of massive government spending and constrained private sector consumption during WWII enabled the deleveraging that commenced in 1933 to continue. By the end of WWII, private debt had fallen to 40% of GDP from its debt-deflation-driven peak of 144% in 1932 (see Figure 6). This low level of private debt, along with the substantial level of fiat-based money created during WWII, low interest rates, and regular government deficits, meant that the financial burden on the private sector in the 1950s and 1960s was trivial. It was as if the slate had been wiped clean by a classical Jubilee.

Not realizing any of this, and certainly not understanding the incredible reluctance of their parents and grandparents to go into debt, the Baby Boomers restarted the borrowing bubble, culminating in the telecommunications, dotcom, and finally Subprime bubbles, which drove private debt to its highest level in American history (and in most of the rest of the developed world).

Contrast that to today, where private debt fell by only 20% from its Great Recession peak of 170% of GDP. It still sits above the previous peak that it was driven to by deflation in 1932. We need to reduce private debt back to its levels during that Golden Age—but we should find a better way of doing so than another World War.

-

A Modern Debt Jubilee

The monetary perspective developed in the previous sections shows that the real-world roles of private and public debt, and of credit and government deficits, are the exact opposite of what the Neoclassical conventional wisdom asserts. Private debt, not government debt, is the primary cause of economic crises. Credit, and not government deficits, is dangerous when it is large relative to GDP. Rising private debt, not rising government debt, is the main indicator of an approaching crisis. Private debt, not government debt, can depress economic activity because it is too high. These insights indicate that the levels of private debt and credit are economic indicators of at least as much importance as the customary ones of the unemployment rate and the inflation rate. They should be monitored as closely, and economic policy should aim to keep them both relatively low.

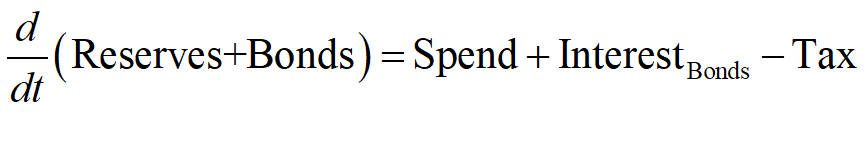

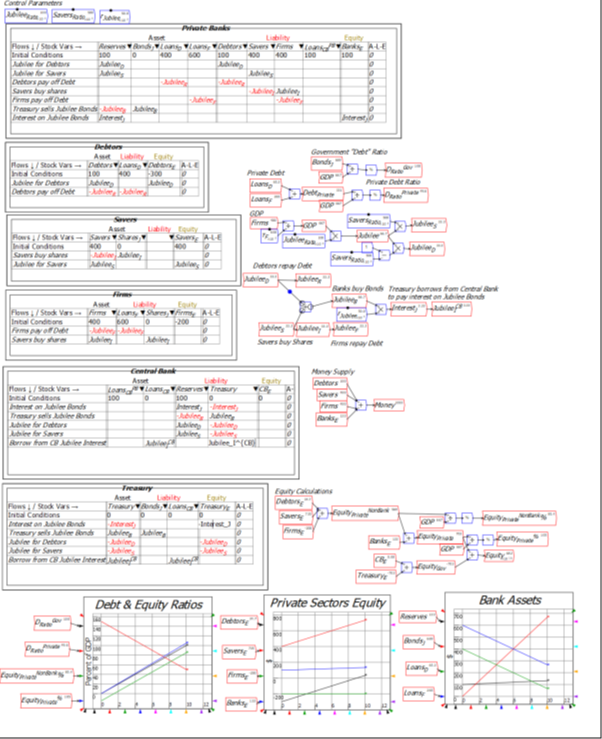

But that leaves the issue of what to do after Neoclassical economics, by not merely ignoring private debt, but by actively arguing in favor of debt-financing of business (Modigliani and Merton 1958), has helped drive private debt to at least three times its Golden Age level. If capitalism is ever to have another Golden Age—and one will be needed to address the challenges of Climate Change—then we need to reduce the private debt to GDP ratio by at least as much as it was reduced during the 1930s and 1940s. This could be done in exactly the same way that the government runs a deficit today, in a way that does not advantage those who gambled with borrowed money over those that did not, and without causing inflation—and even, if it is so desired, without increasing aggregate demand—by what I call a Modern Debt Jubilee.

Figure 12 shows the basic accounting logic of a Modern Debt Jubilee (Coppola 2019). Firstly, the Treasury issues every adult resident, debtor and saver alike, the same sum of fiat-based money. If this amount were $100,000 per American over 15 years old, the total would be $24 trillion—roughly 110% of the USA’s GDP, or 70% of the level of outstanding private sector debt. Those who had bank debt would be required to reduce it by that amount. Those who were debt free, or whose debts were less than $100,000, would be required to buy newly-issued corporate shares, the revenue from which would have to be used to cancel corporate debt and replace it with equity.

The banks would not lose out of this process. Instead, their Reserves would rise by precisely as much as their debt-based assets would fall. Then, they would use these excess reserves to buy Jubilee Bonds, which would generate an income stream for banks in partial compensation for the loss of income from interest on household and corporate debt.

No additional money, or spending power, would be created directly. Instead, there would be an increase in fiat-backed money, and an equivalent decline in credit-back money. For corporations, shareholder equity would rise, and corporate debt would fall. Private debt would go from 150% of GDP to 40% of GDP—roughly the level it was at the start of the Golden Age of Capitalism.

This would also reduce the obscene increase in inequality that has been the direct and deliberate result of the program of “Quantitative Easing” (“QE“) that the Federal Reserve has followed since 2010. As Bernanke himself put it in an OpEd for The Washingon Post, “higher stock prices will boost consumer wealth and help increase confidence, which can also spur spending. Increased spending will lead to higher incomes and profits that, in a virtuous circle, will further support economic expansion” (Bernanke 2010). QE, which initially saw The Fed promise to be a net buyer of bonds from banks to the tune of $80 billion per month, or almost $1 trillion per year, encouraged financial corporations to buy shares in place of the bonds they had sold to The Fed.

This was a—and perhaps the—major factor in the rise of the S&P500 from its nadir of 666 in early 2009 to almost six times as much in 2020. This boosted wealth dramatically—but only the wealth of those who owned shares. The vast majority of the population own no shares directly, and only a trivial fraction of the stock market’s overall valuation via pension schemes and the like. This policy decision, made by and undertaken by the Neoclassical economists who run the Federal Reserve, amplified the inequality already created by the preceding debt-financed bubbles—a point I’ll elaborate upon in the next chapter. It is a policy mistake that should be reversed, and a Modern Debt Jubilee could do it.

You will, I hope, note that actual QE didn’t involve any taxes, and it was entirely a Federal Reserve action, because the increase in The Fed’s liabilities—the huge rise in the Reserves of private banks—was matched by an equivalent increase in The Fed’s assets, its holdings of both government and corporate bonds. Unlike actual QE, a Modern Debt Jubilee would necessarily involve the Treasury, as shown in Figure 12, and the negative equity generated for the Treasury would be identical to the positive equity created for savers and debtors (and the banking system, via interest payments on Jubilee Bonds).

Figure 12: Accounting for a Modern Debt Jubilee

-

Taming “the Roving Cavaliers of Credit”

Some of Marx’s greatest and undeniably truest rhetorical flourishes occurred in Chapter 33 of Volume III of Capital (Marx 1894, Chapter 33), when he discussed the financial system:

A high rate of interest can also indicate, as it did in 1857, that the country is undermined by the roving cavaliers of credit who can afford to pay a high interest because they pay it out of other people’s pockets (whereby, however, they help to determine the rate of interest for all), and meanwhile they live in grand style on anticipated profits. Simultaneously, precisely this can incidentally provide a very profitable business for manufacturers and others. Returns become wholly deceptive as a result of the loan system…

Talk about centralisation! The credit system, which has its focus in the so-called national banks and the big money-lenders and usurers surrounding them, constitutes enormous centralisation, and gives this class of parasites the fabulous power, not only to periodically despoil industrial capitalists, but also to interfere in actual production in a most dangerous manner—and this gang knows nothing about production and has nothing to do with it. (Marx 1894, Chapter 33)

Marx’s disparaging outsider’s remarks about bankers are confirmed by insider accounts today, including ex-banker and philanthropist Richard Vague, whose A Brief History of Doom (Vague 2019) is a magisterial account of the role of bankers, credit and debt in causing all of the world’s major economic crises before Covid-19. Vague acknowledges, as I do, the creative role that credit can play in a capitalist economy:

Take away private debt, and commerce as we know it would slow to a crawl. The world suffered crisis after crisis in the 1800s, but per-capita-GDP increased thirtyfold in that century, and private debt was integral to that growth. Many of those nineteenth-century crises were rooted in the overexpansion of railroads, but they left behind an impressively extensive network of rails from which countries still benefit. (Vague 2019, p. 16)

But he echoes Marx from insider knowledge about the incentives for irresponsible over-lending that are rife in banks:

… financial crises recur so frequently … that we have to wonder why lending booms happen at all. The answer is this: growth in lending is what brings lenders higher compensation, advancement, and recognition. Until a crisis point is reached, rapid lending growth can bring euphoria and staggering wealth… Lending booms are driven by competition, inevitably accompanied by the fear of falling behind or missing out…

Having spent a lifetime in the industry, I can report that there is almost always the desire to grow loans aggressively and increase wealth… So the better and more profound question is, why are there periods in which loan growth isn’t booming? … when lenders are chastened—often in the years following a crisis. (Vague 2019, pp. 7-8)

While financial instability cannot be wholly eliminated from capitalism—for reasons that will become evident in the next chapter—the most egregious elements of irresponsible bank lending can be addressed by limitations on what banks are allowed to lend for—limitations that should be part and parcel of being granted the privilege and power to create money that comes with a banking licence, especially since history provides ample evidence that, without controls, this privilege will be abused. These limitations should constrain or eliminate lending that finances asset price bubbles, and direct lending as much as is possible towards investment and essential consumption rather than speculation.

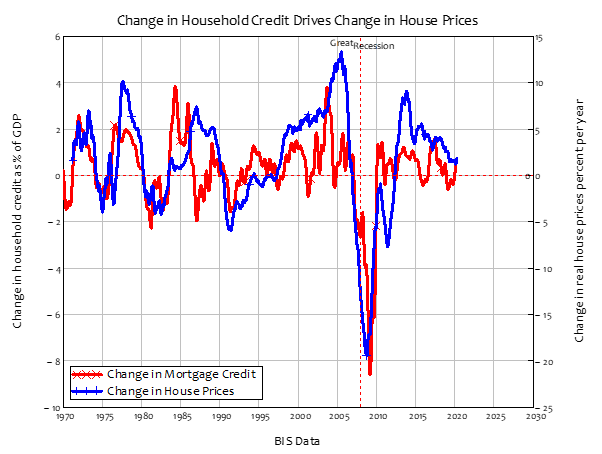

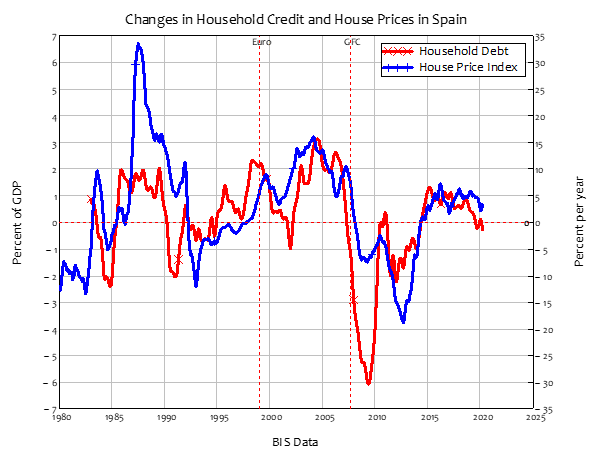

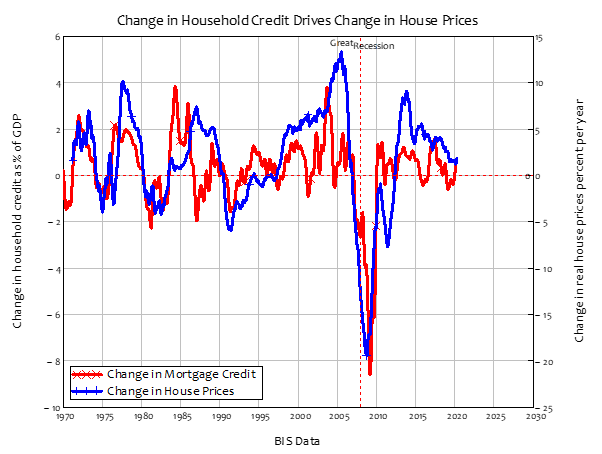

Once the role of credit in aggregate demand is understood, it’s easy to extend this to asset markets, in which credit plays a major role. With mortgage debt as the main means by which houses are purchased, there is a causal relationship between new mortgages—or mortgage credit—and the house price level, and hence between change in mortgage credit, and change in house prices. The same logic applies to change in margin credit, and change in stock prices. The correlation between change in mortgage credit & change in house prices since 1971 is 0.64, while the correlation between change in margin credit and change in Shiller’s CAPE index since 1990, when margin debt began to rise again after 50 years of being below 0.5% of GDP, is also 0.64.

Figure 13: Change in household credit and change in house prices (Correlation 0.64)

This type of borrowing drives asset price bubbles, and does precious little benefit to benefit society. We need means by which this kind of borrowing can be discouraged, while lending for productive purposed can be enhanced.

-

“The Pill”

At present, if two individuals with the same savings and income are competing for a property, then the one who can secure a larger loan wins. This reality gives borrowers an incentive to want to have the loan to valuation ratio increased, which underpins the finance sector’s ability to expand debt for property purchases.

I instead propose basing the maximum debt that can be used to purchase a property on the income (actual or imputed) of the property itself. Lenders would only be able to lend up to a fixed multiple of the income-earning capacity of the property being purchased—regardless of the income of the borrower. A useful multiple would be 10, so that if a property rented for $30,000 p.a., the maximum amount of money that could be borrowed to purchase it would be $300,000.

Under this regime, if two parties were vying for the same property, the one that raised more money via savings would win. There would therefore be a negative feedback relationship between leverage and house prices: a general increase in house prices would mean a general fall in leverage. This would also encourage treating housing as it should be treated: a long-lived consumer good, rather than an object of speculation.

-

Jubilee Shares

The key factor that allows Ponzi Schemes to work in asset markets is the “Greater Fool” promise that a share bought today for $1 can be sold tomorrow for $10. No interest rate, no regulation, can hold against the charge to insanity that such a feasible prospect foments. The vast majority of activity on the stock market is also the sale of existing shares by one speculator to another, which raises no capital for the company in question. The primary market—the sale of new shares by a company to raise capital—is trivial by comparison.

I propose the redefinition of shares in such a way that the enticement of limitless price appreciation can be removed, and the primary market can take precedence over the secondary market. A share bought in an IPO or rights offer would last forever (for as long as the company exists) as now, with all the rights it currently confers. It could be sold once onto the secondary market with all the same privileges. But on its next sale, it would have a life span of 50 years, at which point it would terminate.

The objective of this proposal is to eliminate the appeal of using debt to buy existing shares, while still making it attractive to fund innovative firms or startups via the primary market, and still making purchase of the share of an established company on the secondary market attractive to those seeking an annuity income.

I can envisage ways in which this basic proposal might be refined, while still maintaining the primary objective of making leveraged speculation on the price of existing share unappealing. The termination date could be made a function of how long a share was held; the number of sales on the secondary market before the Jubilee effect applied could be more than one. But the basic idea has to be to make borrowing money to gamble on the prices of existing shares a very unattractive proposition.

-

Entrepreneurial Equity Loans

Entrepreneurs, in Schumpeter’s compelling vision of their role in capitalism’s development (Schumpeter 1934), are people with a good idea but no money with which to turn these ideas into products. Credit to entrepreneurs from banks is almost non-existent, though this function was the basis of Schumpeter’s explanation of the endogeneity of money. And for good reason: most entrepreneurs will fail, and banks that lend to them lose their capital, while only securing an interest-rate return from those entrepreneurs who succeed.

One way to encourage banks to lend to entrepreneurs in return for equity, rather than debt, via “Entrepreneurial Equity Loans” (EELs). Banks would still lose money on those entrepreneurs that failed, but could make a capital gain as well as a flow of dividends on those entrepreneurs who succeeded.

-

Shifting the monetary paradigm

I am often asked what I would keep of Neoclassical economics in a new paradigm. My answer is that I would keep as much of Neoclassical economics as modern astronomy kept of Ptolemaic astronomy—which is to say, nothing at all. On its own, that answer may seem both arrogant and flippant: surely there is something of value in all the work done by Neoclassical economists?

There are skerricks of merit in the entire edifice. But I hope that is evident after this chapter on money that nothing of worth remains of the Neoclassical perspective on money and banking, once the reality that banks create money is accepted. Rather than being irrelevant to macroeconomics, banks, private debt, and money, are essential. Rather than playing no role in macroeconomics, credit is a significant component of aggregate demand and income, and, given its volatility, it is the “causa causans” (Keynes 1937, p. 221) that drives macroeconomics. Financial crises, rather than being “Black Swans”, are products of credit turning negative. Private debt, not government debt, is dangerous when it is high relative to GDP. Governments should normally run deficits to create identical surpluses for the non-government sectors. Government debt does not burden future generations but instead generates monetary assets for current ones. All the Neoclassical arguments about money are invalid: there is nothing at all to keep.

The same applies to the next, more technical failing of Neoclassical economics: its obsession with modelling the economy as if it has a stable equilibrium.

-

References

Aristotle and H. D. P. L. (translator) (350 BCE [1952]). Meteorologica / Aristotle. London, Heinemann.

Bernanke, B. (2010). Aiding the Economy: What the Fed Did and Why. The Washington Post, The Washington Post.

Bernanke, B. S. (2000). Essays on the Great Depression. Princeton, Princeton University Press.

Census, B. o. (1949). Historical Statistics of the United States 1789-1945. B. o. t. Census. Washington, United States Government.

Census, B. o. (1975). Historical Statistics of the United States Colonial Times to 1970. B. o. t. Census. Washington, United States Government.

Chambers, C. (2019). “Bitcoin Really Is Money, Here’s Why.” Forbes

https://www.forbes.com/sites/investor/2019/02/15/bitcoin-really-is-money-heres-why/?sh=f01d78679d22.

Coolidge, C. (1928). State of the Union Address: Calvin Coolidge (December 4, 1928).

Coppola, F. (2019). People’s Quantitative Easing. Cambridge, Polity Press.

Deutsche Bundesbank (2017). “The role of banks, non- banks and the central bank in the money creation process.” Deutsche Bundesbank Monthly Report

April 2017: 13-33.

Fisher, I. (1929). Fisher sees stocks permanently high. New York Times. New York, New York Times. 16 October 1929.

Fisher, I. (1932). Booms and Depressions: Some First Principles. New York, Adelphi.

Fisher, I. (1933). “The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions.” Econometrica

1(4): 337-357.

Fontana, G. and R. Realfonzo, Eds. (2005). The Monetary Theory of Production: Tradition and Perspectives. Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan.

Fullwiler, S. T. (2013). “An endogenous money perspective on the post-crisis monetary policy debate.” Review of Keynesian Economics

1(2): 171–194.

Gleeson-White, J. (2011). Double Entry. Sydney, Allen and Unwin.

Graziani, A. (1989). “The Theory of the Monetary Circuit.” Thames Papers in Political Economy

Spring: 1-26.

Holmes, A. R. (1969). Operational Constraints on the Stabilization of Money Supply Growth. Controlling Monetary Aggregates. F. E. Morris. Nantucket Island, The Federal Reserve Bank of Boston: 65-77.

Ireland, P. N. (2011). “A New Keynesian Perspective on the Great Recession.” Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking

43(1): 31-54.

Keen, S. (1995). “Finance and Economic Breakdown: Modeling Minsky’s ‘Financial Instability Hypothesis.’.” Journal of Post Keynesian Economics

17(4): 607-635.

Kelton, S. (2020). The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and the Birth of the People’s Economy. New York, PublicAffairs.

Keynes, J. M. (1937). “The General Theory of Employment.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics

51(2): 209-223.

Krugman, P. (2009). “Liquidity preference, loanable funds, and Niall Ferguson (wonkish).” The Conscience of a Liberal

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/05/02/liquidity-preference-loanable-funds-and-niall-ferguson-wonkish/.

Krugman, P. (2011). “Debt Is (Mostly) Money We Owe to Ourselves.” The Conscience of a Liberal

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/12/28/debt-is-mostly-money-we-owe-to-ourselves/ 2012.

Krugman, P. (2011). “Liquidity Preference and Loanable Funds, Still (Wonkish).” The Conscience of a Liberal

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/06/03/liquidity-preference-and-loanable-funds-still-wonkish/.

Krugman, P. (2012). End this Depression Now! New York, W.W. Norton.

Krugman, P. (2013). “Commercial Banks As Creators of “Money”.” The Conscience of a Liberal

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/08/24/commercial-banks-as-creators-of-money/.

Krugman, P. (2014). “A Monetary Puzzle.” The Conscience of a Liberal

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/04/28/a-monetary-puzzle/.

Krugman, P. (2015). “Debt Is Money We Owe To Ourselves.” New York Times

https://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/02/06/debt-is-money-we-owe-to-ourselves/?_r=0.

Krugman, P. (2015). “Debt: A Thought Experiment.” New York Times

https://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/02/06/debt-a-thought-experiment/.

Kumhof, M. and Z. Jakab (2015). Banks are not intermediaries of loanable funds — and why this matters. Working Paper. London, Bank of England.

Kumhof, M., R. Rancière and P. Winant (2015). “Inequality, Leverage, and Crises.” The American Economic Review

105(3): 1217-1245.

Mankiw, N. G. (2016). Macroeconomics. New York, Macmillan.

Marglin, S. A. and J. B. Schor (1992). Golden Age of Capitalism. Oxford, UK, Clarendon Press Oxford.

Marx, K. (1894). Capital Volume III. Moscow, International Publishers.

McLeay, M., A. Radia and R. Thomas (2014). “Money creation in the modern economy.” Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin

2014 Q1: 14-27.

McLeay, M., A. Radia and R. Thomas (2014). “Money in the modern economy: an introduction.” Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin

2014 Q1: 4-13.

Minsky, H. (1963). Can “It” Happen Again? Banking and Monetary Studies. D. Carson. Homewood, Richard D Irwin: 101-111.

Minsky, H. P. (1963). Can “It” Happen Again? Banking and Monetary Studies. D. Carson. Homewood, Illinois, Richard D. Irwin: 101-111.

Minsky, H. P. (1975). John Maynard Keynes. New York, Columbia University Press.

Minsky, H. P. (1977). “The Financial Instability Hypothesis: An Interpretation of Keynes and an Alternative to ‘Standard’ Theory.” Nebraska Journal of Economics and Business

16(1): 5-16.

Minsky, H. P. (1978). “The Financial Instability Hypothesis: A Restatement.” Thames Papers in Political Economy

Autumn 1978.

Minsky, H. P. (1982). Can “it” happen again? : essays on instability and finance. Armonk, N.Y., M.E. Sharpe.

Minsky, H. P. (1990). Longer Waves in Financial Relations: Financial Factors in the More Severe Depressions. Monetary theory. T. Mayer. Aldershot, U.K., Elgar: 352-363.

Minsky, H. P. and M. D. Vaughan (1990). “Debt and Business Cycles.” Business Economics

25(3): 23-28.

Mirowski, P. (2020). The Neoliberal Ersatz Nobel Prize. Nine Lives of Neoliberalism. D. Plehwe, Q. Slobodian and P. Mirowski. London, Verso: 219-254.

Modigliani, F. and H. M. Merton (1958). “The Cost of Capital, Corporation Finance and the Theory of Investment.” The American Economic Review

48(3): 261-297.

Moore, B. J. (1979). “The Endogenous Money Stock.” Journal of Post Keynesian Economics

2(1): 49-70.

Moore, B. J. (1988). Horizontalists and Verticalists: The Macroeconomics of Credit Money. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Moore, B. J. (1997). “Reconciliation of the Supply and Demand for Endogenous Money.” Journal of Post Keynesian Economics

19(3): 423-428.

Moore, B. J. (2001). Some Reflections on Endogenous Money. Credit, interest rates and the open economy: Essays on horizontalism. L.-P. Rochon and M. Vernengo. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham: 11-30.

Offer, A. and G. Söderberg (2016). The Nobel Factor: The Prize in Economics, Social Democracy, and the Market Turn. New York, Princeton University Press.

Roberts, A. (2012). America’s first Great Depression: economic crisis and political disorder after the Panic of 1837. Ithaca, Cornell University Press.

Schumpeter, J. A. (1934). The theory of economic development : an inquiry into profits, capital, credit, interest and the business cycle. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press.

Sennholz, H. F., Ed. (1975). Gold is Money. London, Greenwood Press.

Taleb, N. N. (2010). The black swan : the impact of the highly improbable / Nassim Nicholas Taleb. London, London : Penguin.

Vague, R. (2019). A Brief History of Doom: Two Hundred Years of Financial Crises. Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press.

Werner, R. A. (2014). “Can banks individually create money out of nothing? — The theories and the empirical evidence.” International Review of Financial Analysis

36(0): 1-19.

Werner, R. A. (2014). “How do banks create money, and why can other firms not do the same? An explanation for the coexistence of lending and deposit-taking.” International Review of Financial Analysis

36(0): 71-77.

We can now classify parts of the table as aggregate expenditure and aggregate income. The negative of the sum of the diagonal elements is aggregate expenditure. The sum of the off-diagonal elements is aggregate income. They are necessarily identical.

We can now classify parts of the table as aggregate expenditure and aggregate income. The negative of the sum of the diagonal elements is aggregate expenditure. The sum of the off-diagonal elements is aggregate income. They are necessarily identical.

When you add up expenditure and income in this table, Credit cancels out: for every positive entry for Credit in either Aggregate Demand (the negative of the sum of the diagonal cells) or Aggregate Income (the sum of the off-diagonal cells), there’s an offsetting negative entry that cancels it out. The only effect of lending on this model of the economy is that Interest payments turn up as part of both expenditure and income:

When you add up expenditure and income in this table, Credit cancels out: for every positive entry for Credit in either Aggregate Demand (the negative of the sum of the diagonal cells) or Aggregate Income (the sum of the off-diagonal cells), there’s an offsetting negative entry that cancels it out. The only effect of lending on this model of the economy is that Interest payments turn up as part of both expenditure and income:

The key outcome is that Credit does not cancel out, as it does in Loanable Funds: there is a single entry for Credit in Aggregate Expenditure—it finances part of the Household Sector’s purchases from the Manufacturing Sector—and a single entry in Aggregate Income—where it is part of the Manufacturing Sector’s income:

The key outcome is that Credit does not cancel out, as it does in Loanable Funds: there is a single entry for Credit in Aggregate Expenditure—it finances part of the Household Sector’s purchases from the Manufacturing Sector—and a single entry in Aggregate Income—where it is part of the Manufacturing Sector’s income:

Each crisis turned around only when the decline of credit stopped. But the renewed growth engendered by rising credit came at the expense of a rising private debt to GDP ratio, with this rise terminated either by another crisis, or by wars that drove the private debt ratio down dramatically because of the “War Economy” boost to GDP: nominal GDP growth reached 32% p.a. during the US Civil War in (1861-65), 29% during WWI (1914-1918), and 29% again during WWII (1939-45), far exceeding the maximum growth rate of credit during those periods (0.2% of GDP p.a., 8.6% and 4.5% respectively).

Each crisis turned around only when the decline of credit stopped. But the renewed growth engendered by rising credit came at the expense of a rising private debt to GDP ratio, with this rise terminated either by another crisis, or by wars that drove the private debt ratio down dramatically because of the “War Economy” boost to GDP: nominal GDP growth reached 32% p.a. during the US Civil War in (1861-65), 29% during WWI (1914-1918), and 29% again during WWII (1939-45), far exceeding the maximum growth rate of credit during those periods (0.2% of GDP p.a., 8.6% and 4.5% respectively).