Support my research at https://www.patreon.com/ProfSteveKeen

Minsky is, and will remain, Open Source software. I will also always post the latest version of Minsky here too, for Windows and Apple PC (see the uploads at the end of this post). But though the Open Source repositories SourceForge and Github will continue to host the source-code for Minsky, no binaries will be posted there past the current version (version 2.10).

For new binaries, the SourceForge and Github Minsky pages will direct users to a new Patreon page: https://www.patreon.com/hpcoder.

The reasons for this move is simple: to raise development funding, and to build a user community.

Minsky has never received funding from the conventional research funding bodies like the UK’s Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), or Australia’s Australian Research Council (ARC). This is simply because, with about 80% of academic economists being Neoclassical, virtually 100% of the referees are Neoclassical. Non-orthodox projects like Minsky haven’t got a chance.

All Minsky‘s funding to date has come from just four sources:

That’s about $300,000, which is peanuts in software development terms. Despite this, Minsky is already a very innovative tool for system dynamics in general, and economic and monetary dynamics in particular. Each month, between 200 and 400 people download it from SourceForge.

Figure 1: Monthly downloads of Minsky since January 2018

What we are hoping is that at least 50-100 of those each month will be willing to pay $1 a month via Patreon to do so. The money raised will then employ Russell to maintain and extend the program.

I don’t expect anyone who’s supporting me on Patreon right now to sign up (though I wouldn’t object either!). You’re already supporting me here, and that’s more than enough. We just hope that users who are curious enough to download Minsky will also be curious enough to pay $1 a month (plus the VAT overhead!) to help us continue to develop it.

I give my time to develop Minsky for free of course—thanks to support I get from my Patrons already. But as a self-employed programmer, Russell has to earn a living, and he charges about US$100 an hour for his time.

Given Russell’s skills in programming, mathematics, big data, physics, and complex systems, this is a bargain.

I’ll never forget one telling incident on this front.

In my second-last year at the University of Western Sydney, a top notch young computer science student signed up for my course on Behavioural Economics and Finance: Nathan Moses. His essay was a C++ written, DOS-based, multi-agent simulation of monetary dynamics. It was so good that (a) I got him to give a lecture to the class on it, and (b) I gave him 22 out of 20 for his essay.

The next year, Nathan started a computer-science-degree project with two other friends to port Minsky to the Web, and wrote a user interface in which multiple people could work simultaneously on the same model. It worked, although there wasn’t time to add the underlying ODE engine beneath the GUI. But it was so good that I hoped to hire Nathan (& Kevin Pereira) if I got enough funding on Kickstarter.

That didn’t come to pass, but for a while during the Kickstarter campaign, we were collaborating on Minsky, and Nathan and Kevin checked out Russell’s existing code, just in case I could raise the funds to employ them.

Nathan walked into our next meeting and said, and I quote: “I used to think I was a hotshot C++ programmer until I saw Russell’s code”.

Patreon also offers two advantages that aren’t available on the Open Source repositories: the capacity for users to interact with other users, and to get some feedback from myself and Russell; and the capacity for us to know who has downloaded Minsky, and over time, to find out whether, why and how they’re using it. Downloads from SourceForge are completely anonymous, and all we know is metadata—how many people have downloaded it, from which countries, using which operating systems.

With a Patreon page, there is a capacity for discussion between users, as there is on this site, plus feedback to myself and Russell (we’ll be co-administrators of that site, though all of the funding will go to him to work on Minsky.

I’ll let you all know when the new Patreon page for Minsky goes live. The rest of this post is here just to provide graphics to use the page: images on Patreon must come from a website, so I’m placing them here so that we can link to them from the new page.

Figure 2: Basic Keen model of Minsky’s Financial Instability Hypothesis

Figure 3: Extended Keen model including prices but no government

Figure 4: Model of the Portuguese economy (by Pedro Pratas)

Figure 5: Bank Originated Money and Debt

Figure 6: The double pendulum

Figure 7: Keen model derived from macroeconomic definitions, with nonlinear behavioural functions

Figure 8: Lorenz’s model of fluid dynamics

Noah Smith (who tweets as @Noahopinion) made this tweet this morning, in response to the latest “Sokal hoax”, in which academics submit a nonsense paper to a journal which then publishes it:

5/The reason I know this is because of econ.

If you wanted to “prove” that econ was bullshit, you wouldn’t even have to Sokal hoax any journal. You could just pull real examples from the literature.

There are some BAAAD papers out there.

But are most econ papers bad? No.

— Noah Smith (@Noahpinion) 4 October 2018

Cameron Murray observed in response that he often felt he was reading a Sokal hoax when he read economics textbooks:

Unfortunately, sometimes I read an economics textbook and wonder if it’s a Sokal hoax!@rethinkecon @UnlearningEcon https://t.co/QsPgcTCLA8

— Cameron Murray (@DrCameronMurray) 4 October 2018

That set off a brainwave for me. Textbooks are in fact the places that “Sokal Hoax” calibre nonsense in mainstream papers get sanitized sufficiently to hide the nonsense. These nonsense papers make assumptions or “logical” steps that any sane non-economist would think must be part of a hoax. And yet they go on to dramatically influence the profession. So I suggested that we institute a “Nobble Prize in Economics” to recognise–or rather expose–these papers:

Now that’s a good question: what’s your favorite actual, influential economics paper, that any non-economist would think was a Sokal hoax? @rethinkecon @UnlearningEcon @PostCrashEcon @Renegade_Inc

We can award it The Nobble Prize In Economics! https://t.co/IeG5uR6TAI pic.twitter.com/kwSCtp9IXe— Steve Keen (@ProfSteveKeen) 4 October 2018

This is actually a serious issue, and maybe a way to break the veneer of science that still protects mainstream economics to this day. So when I have time (now there’s a nonsense assumption at present!) I’ll see if I can institute and get funded a Nobble Prize in Economics, to assemble a list of all the absurd papers that have made economics into what it is today.

There’s tons. Cause is economists wanted particular results, but mathematical logic or empirical data denied it to them. So they make bonking mad assumptions to sidestep the problem, and the discipline swallows them whole because it wants those results. #NobblePrizeInEconomics

— Steve Keen (@ProfSteveKeen) 4 October 2018

The funding, of course, wouldn’t go to the original authors. I’m open to ideas as to how they might be employed.

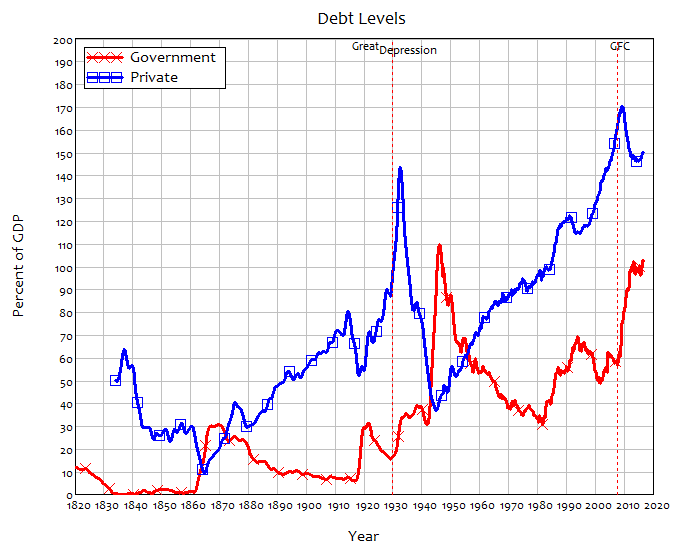

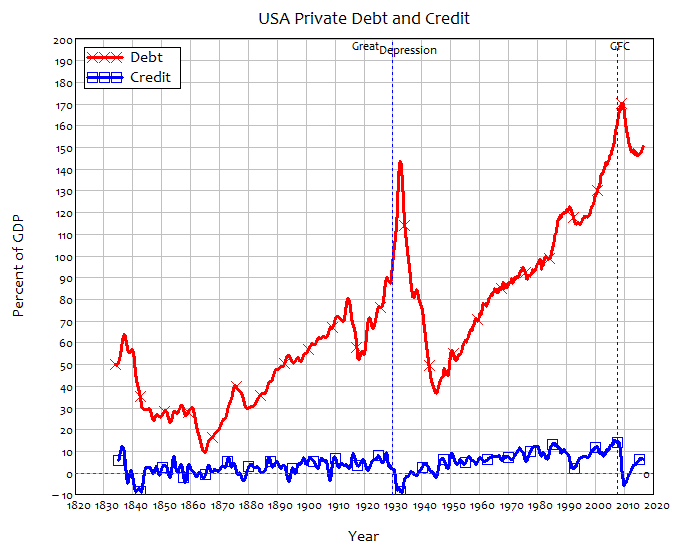

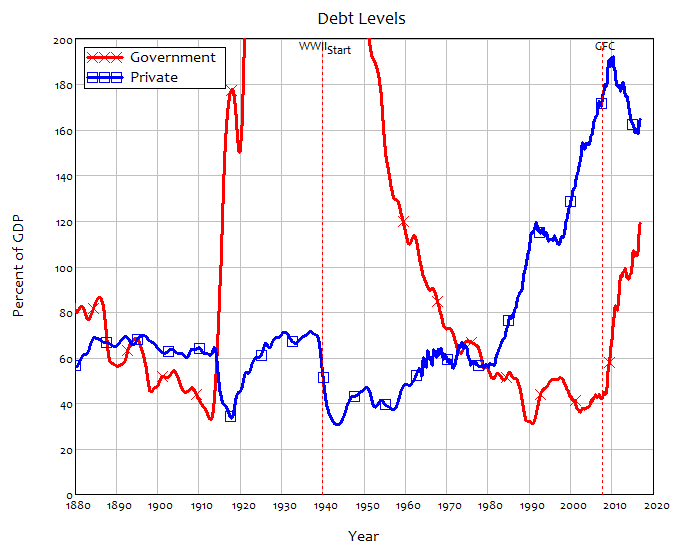

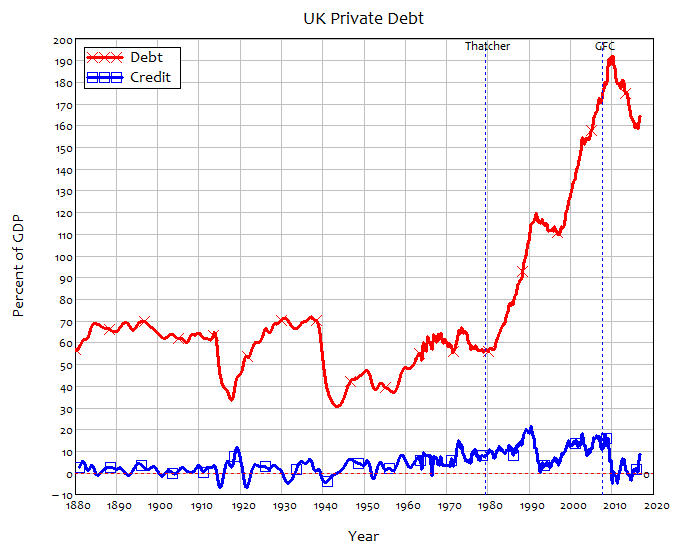

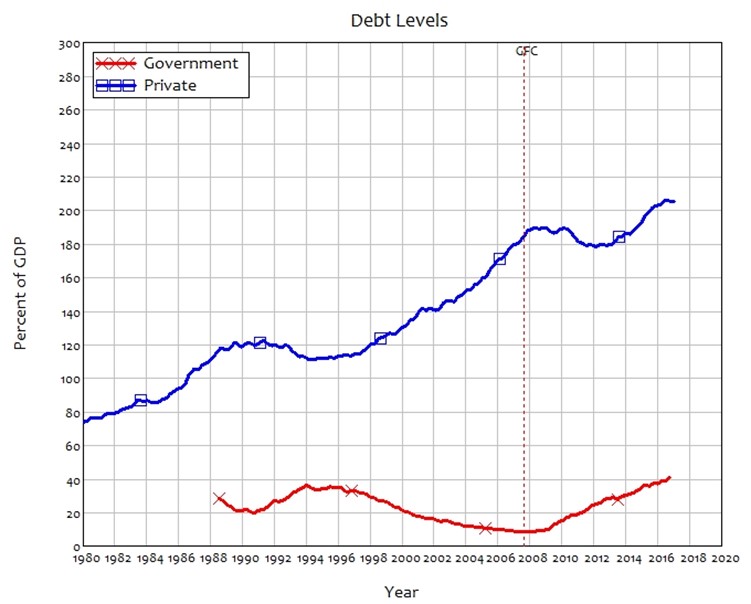

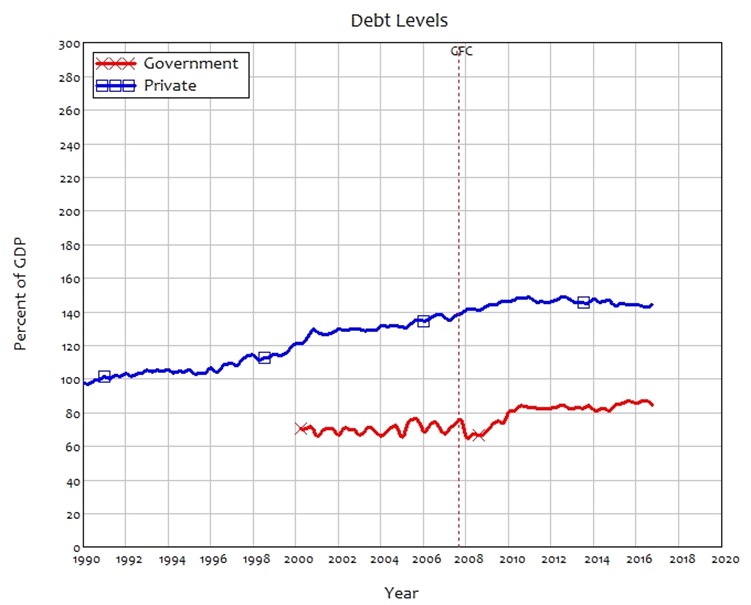

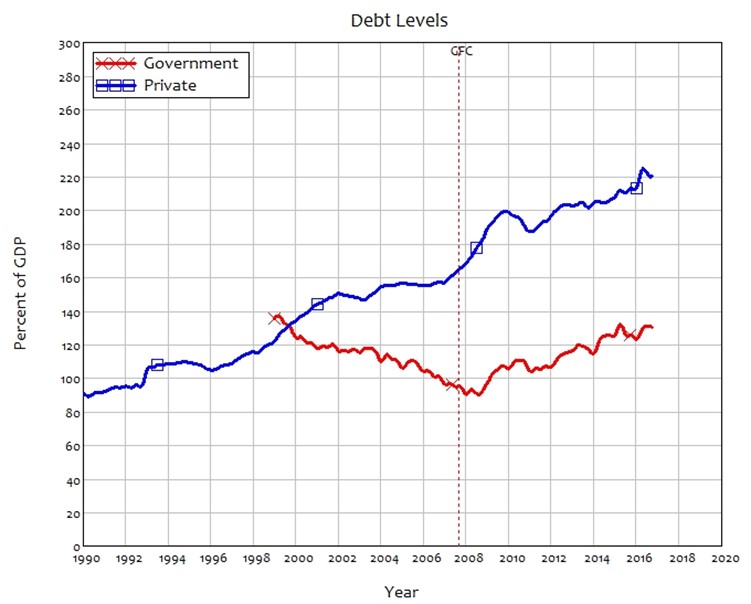

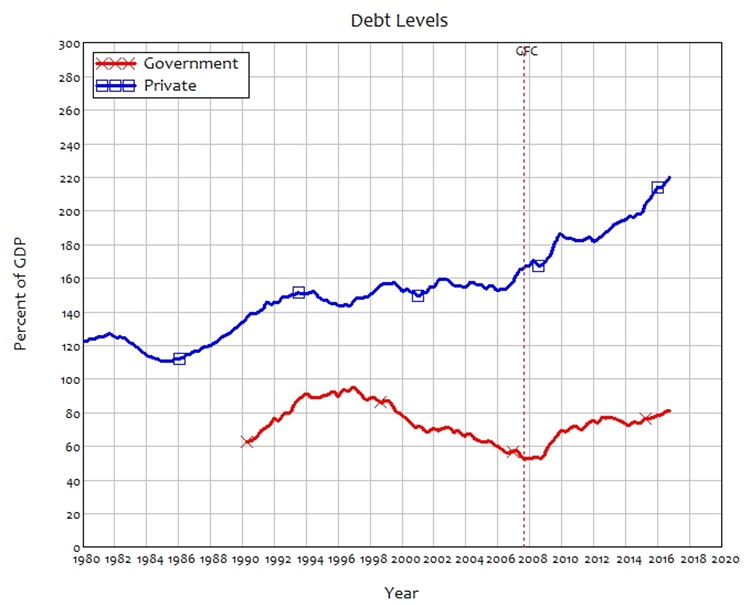

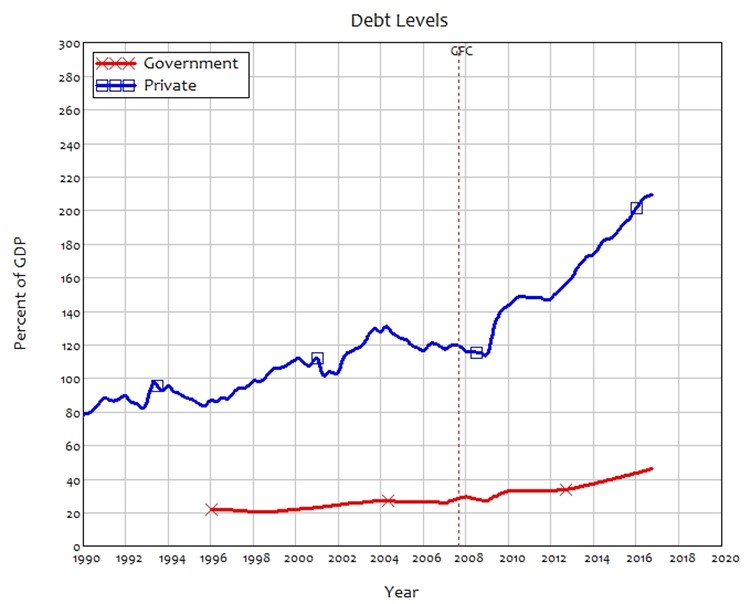

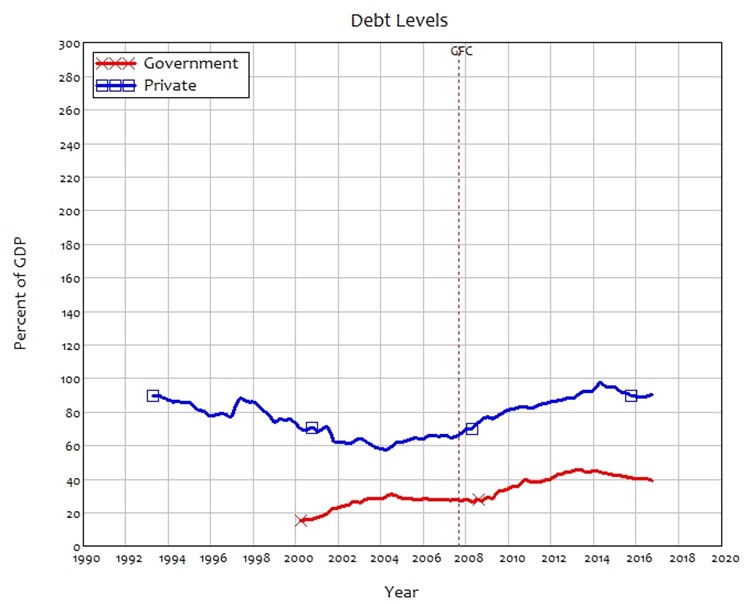

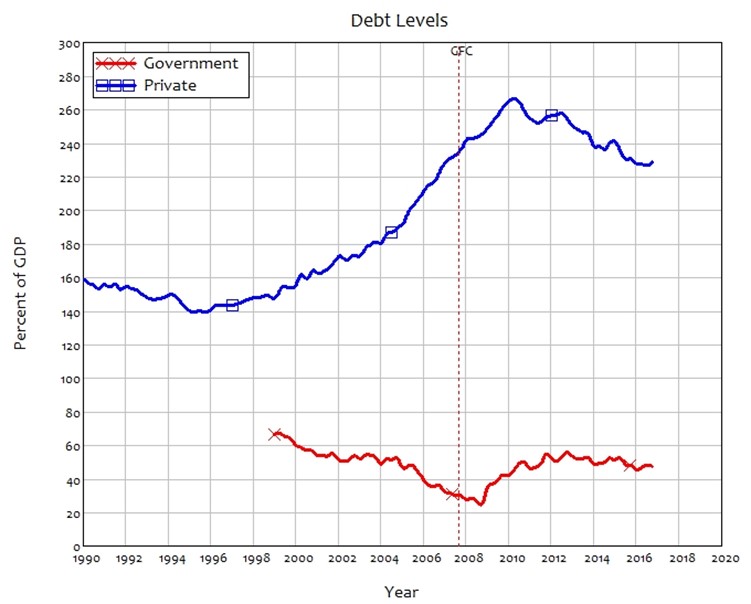

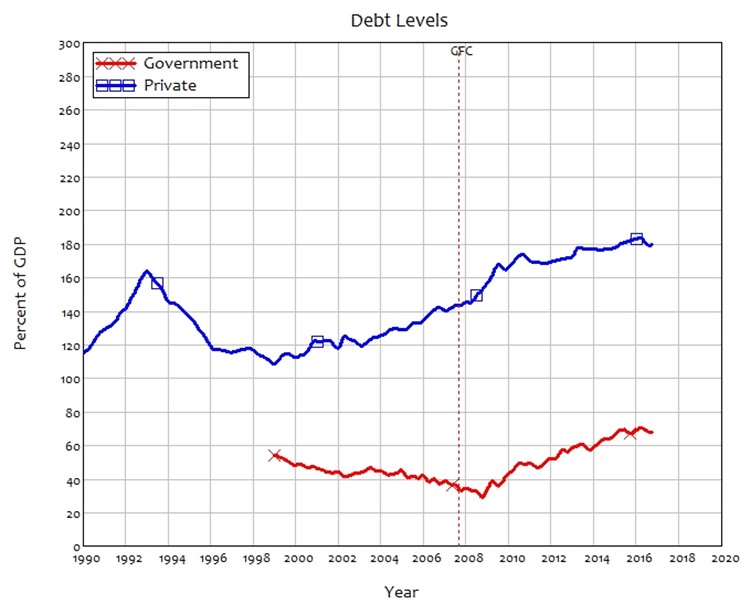

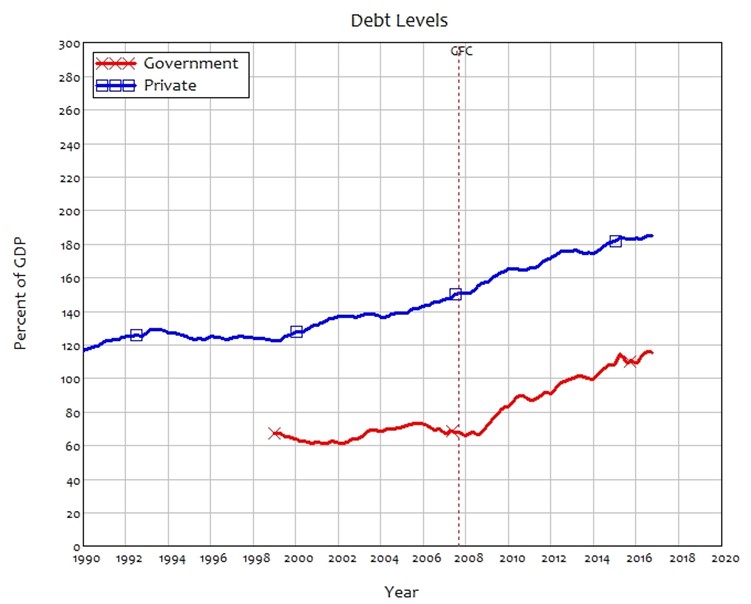

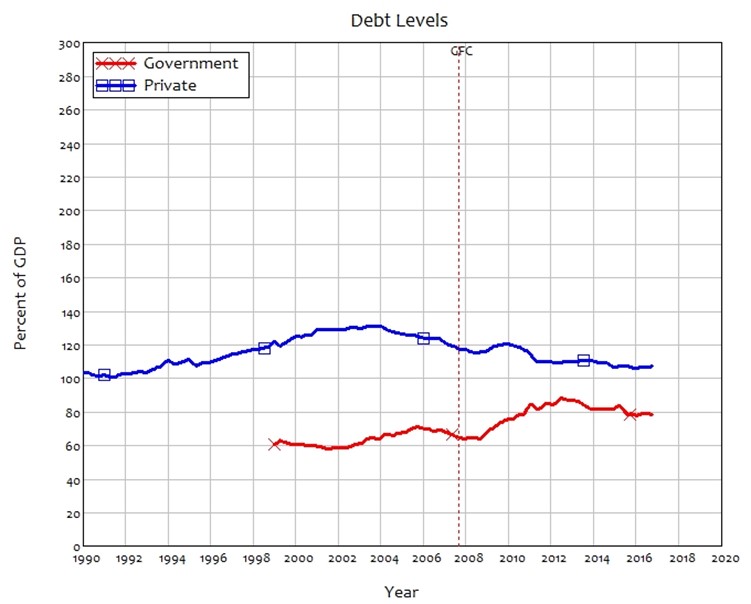

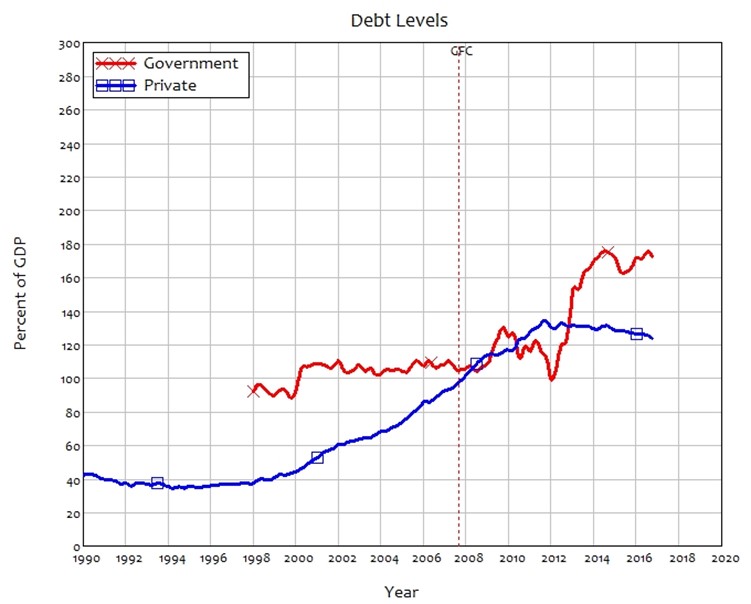

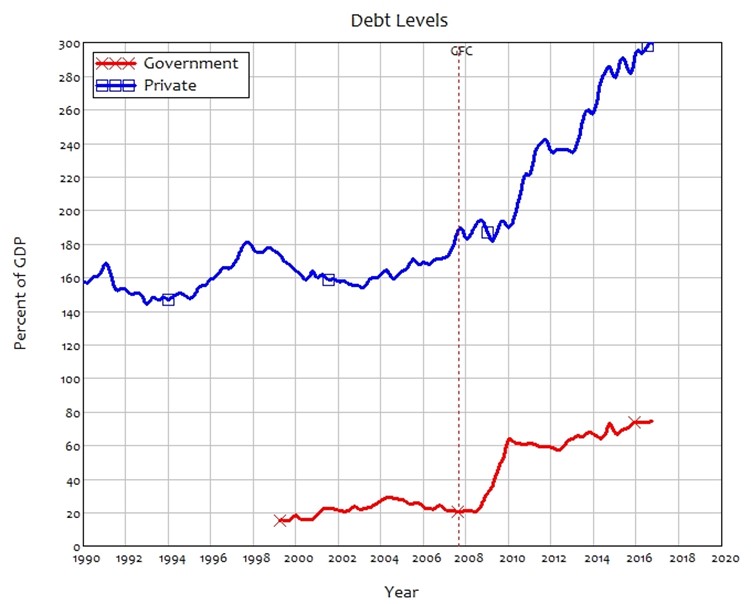

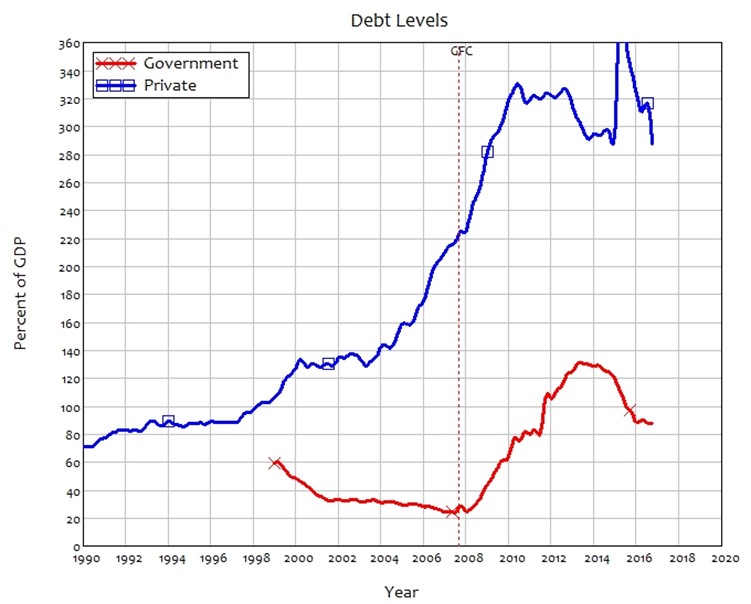

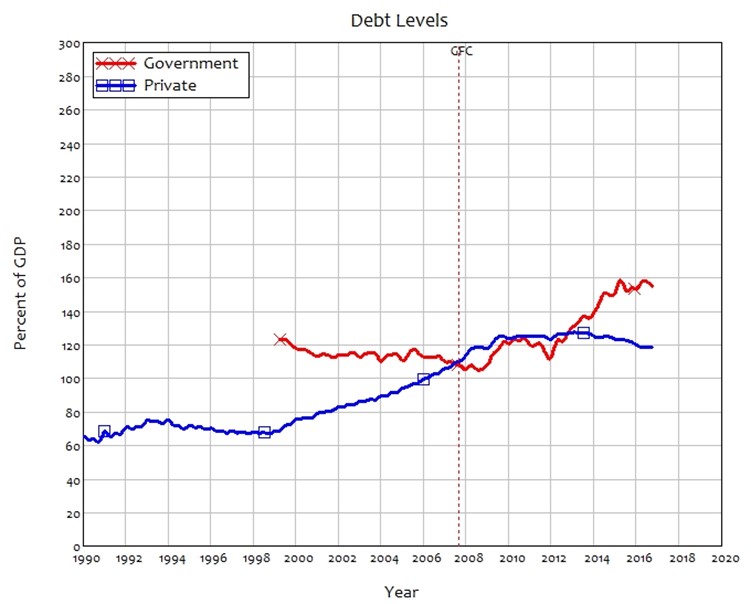

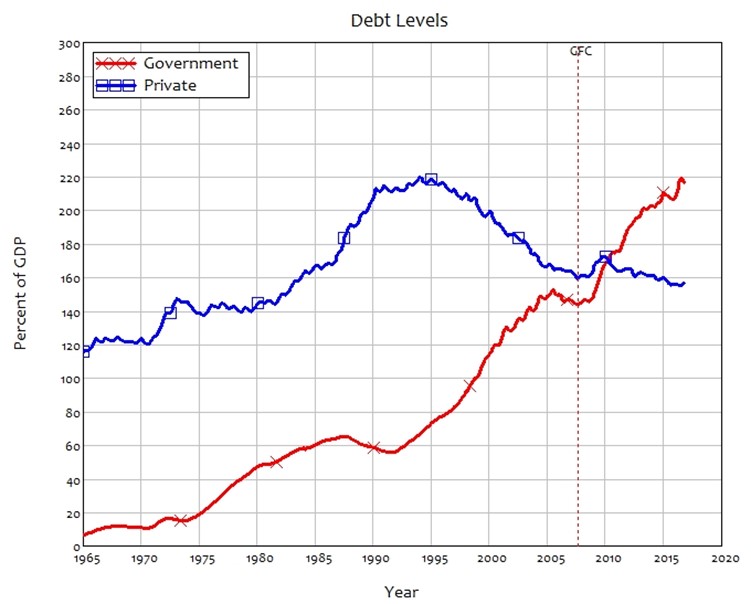

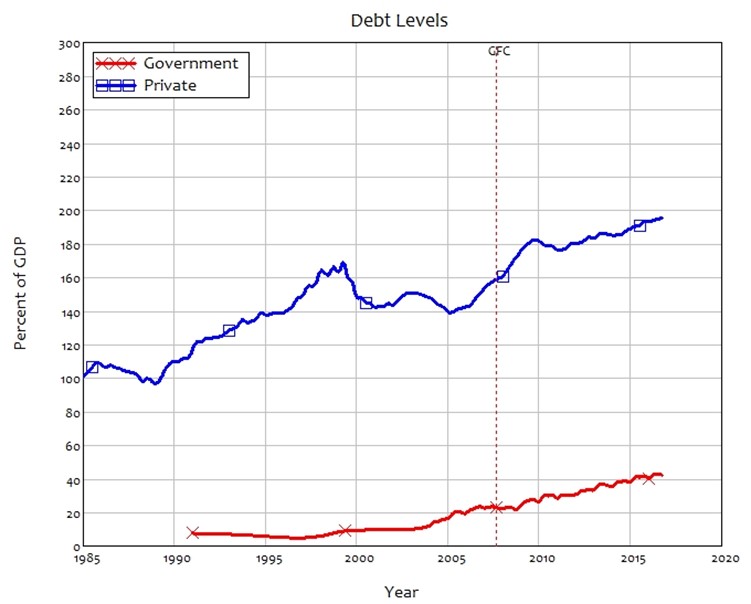

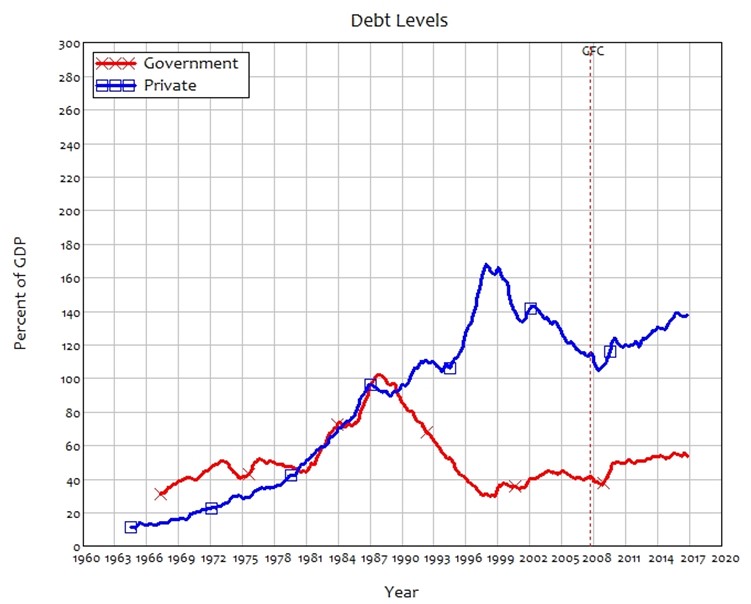

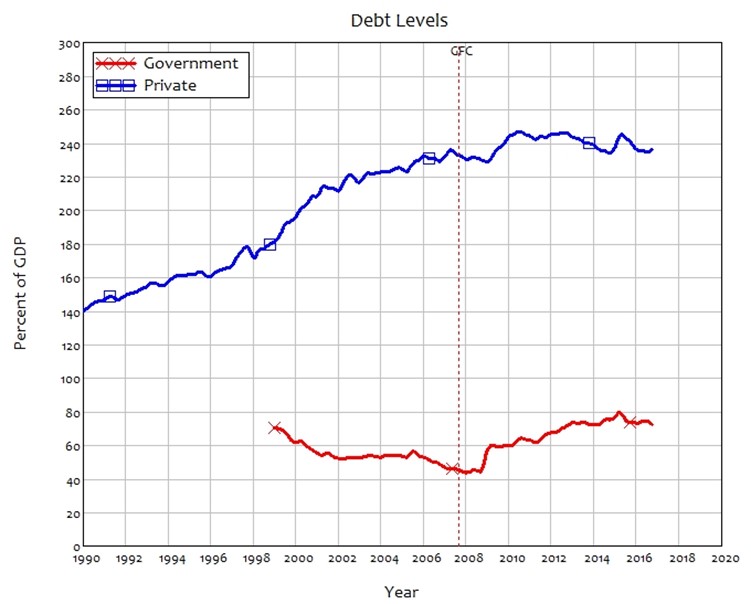

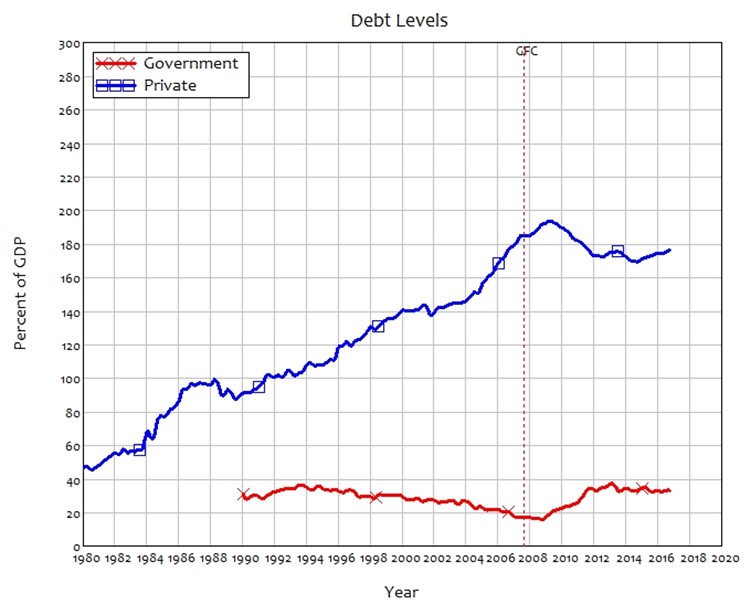

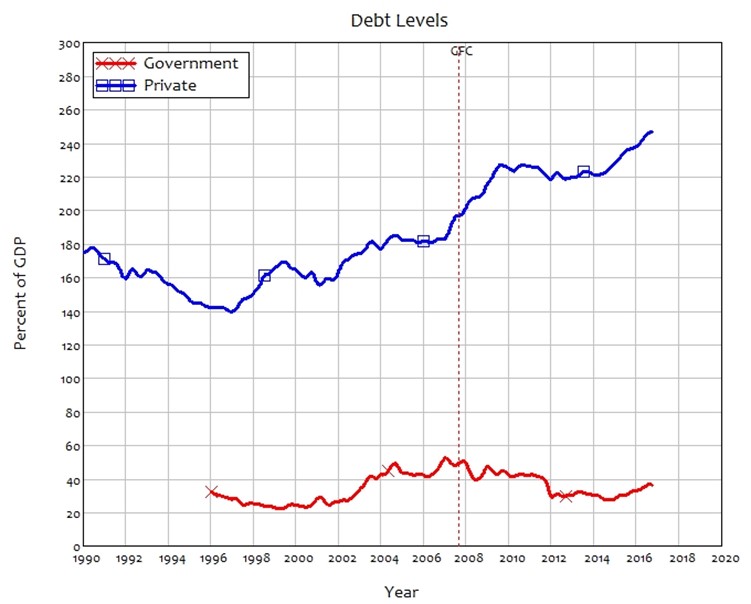

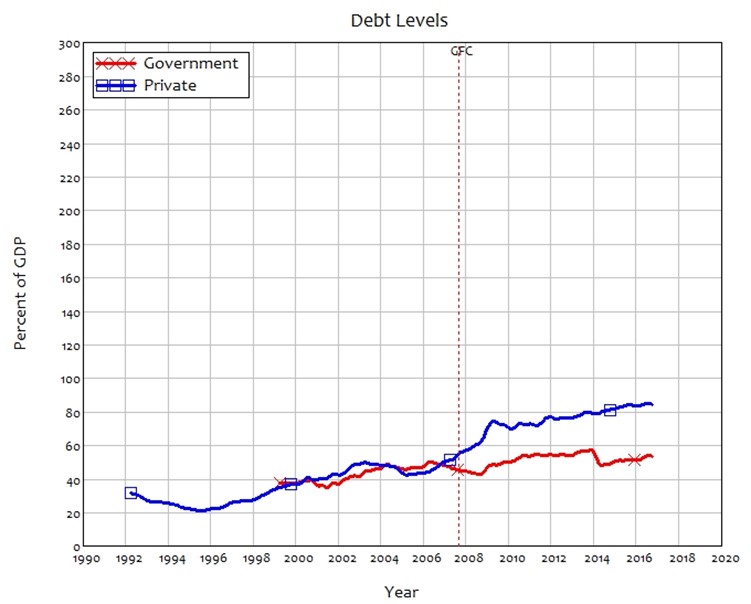

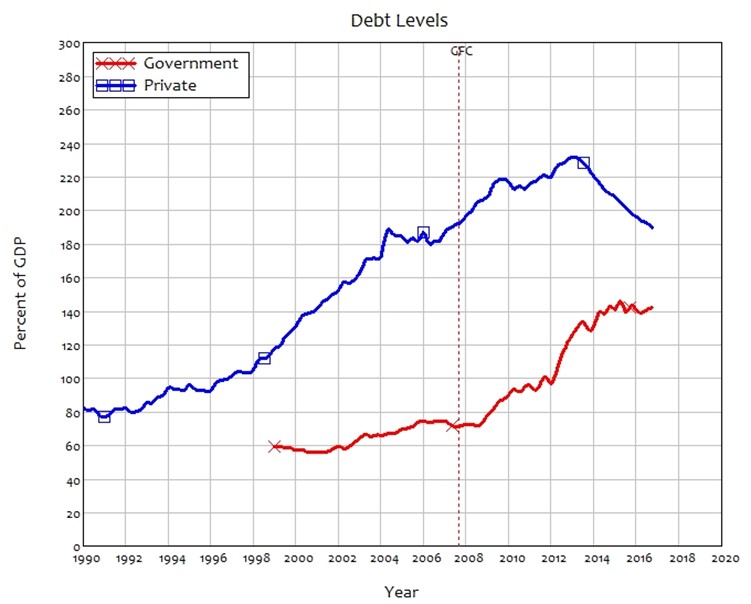

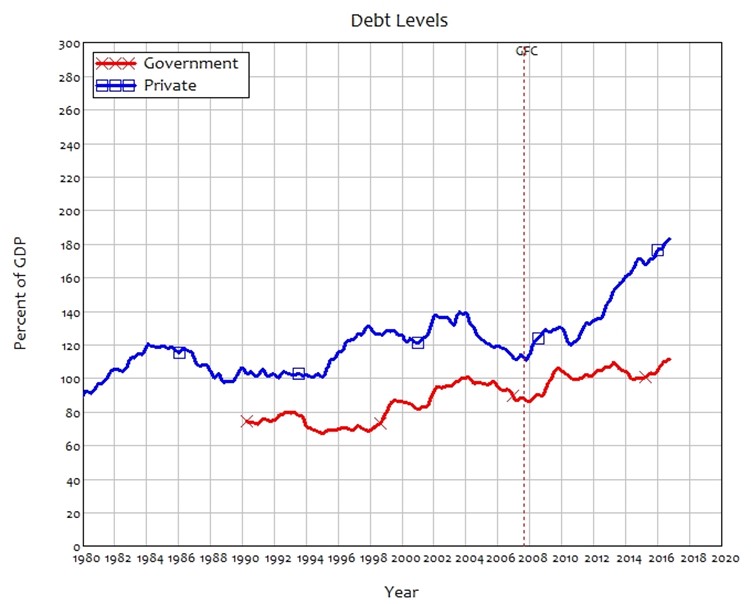

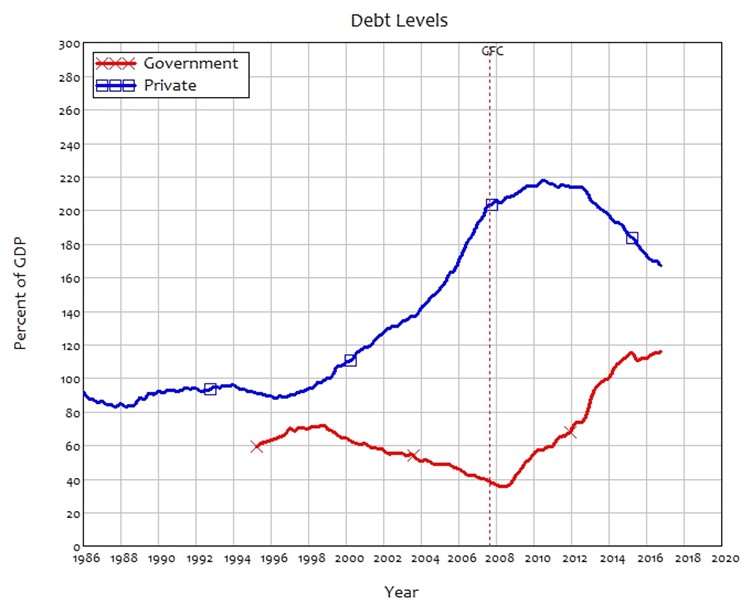

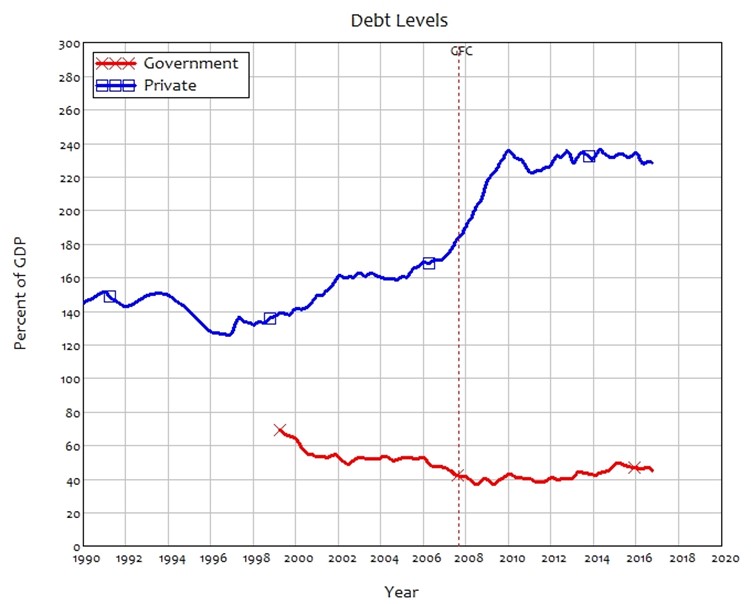

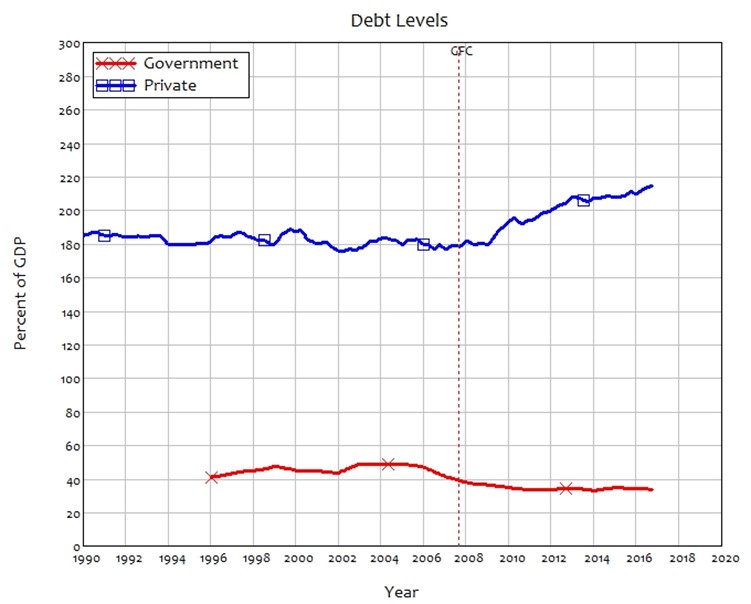

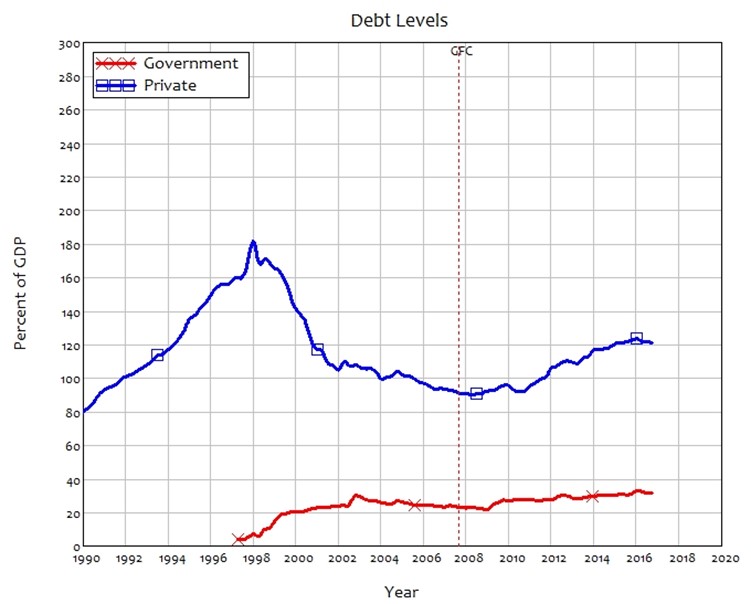

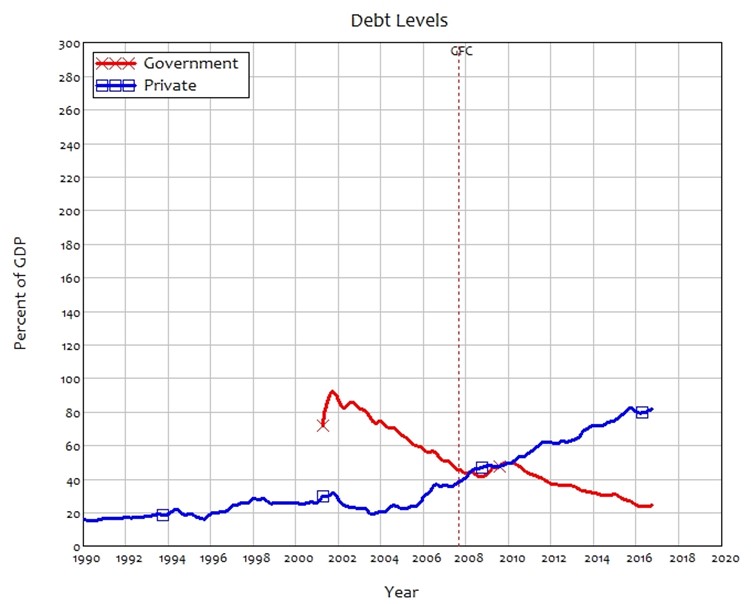

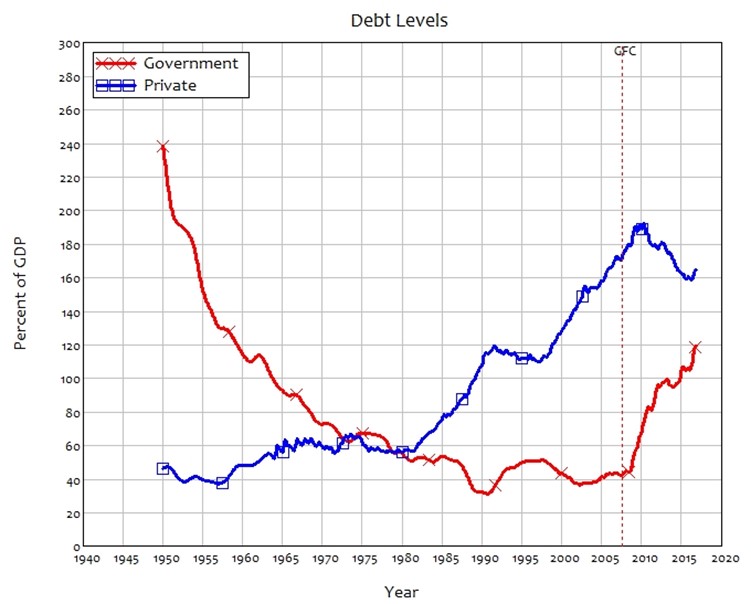

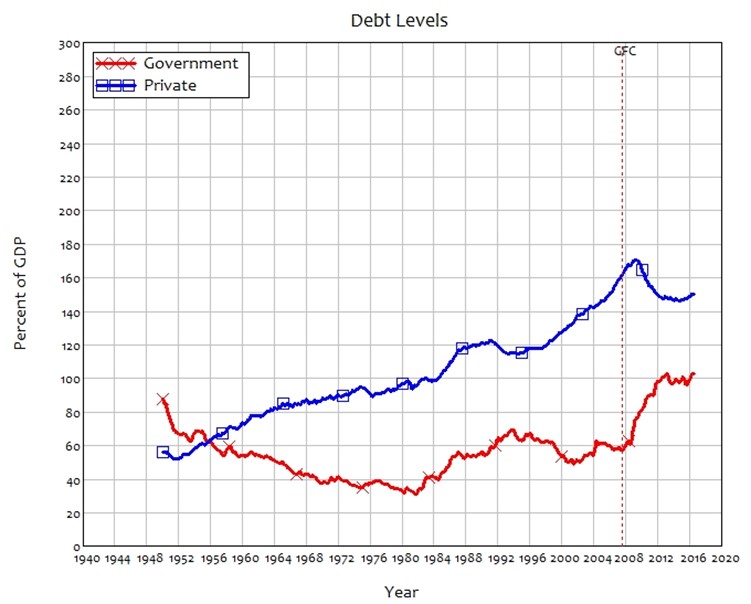

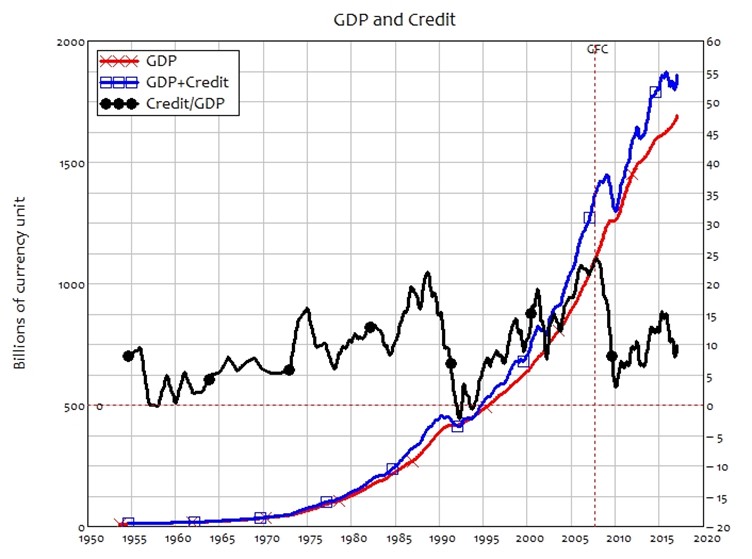

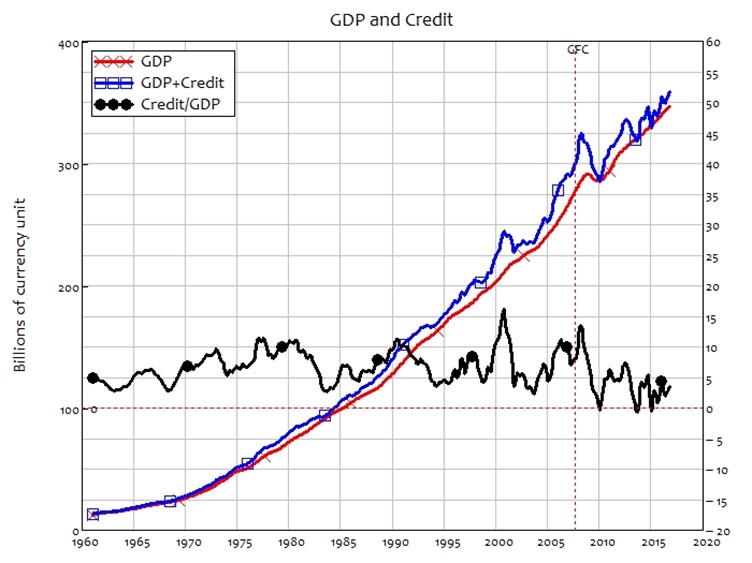

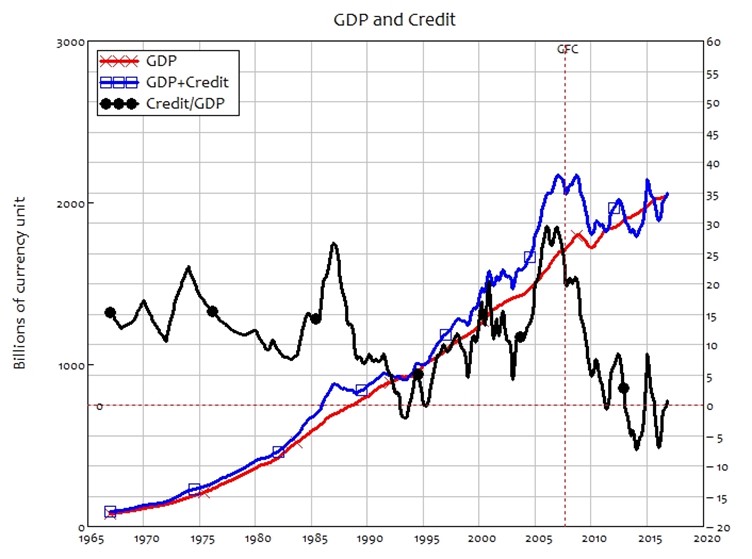

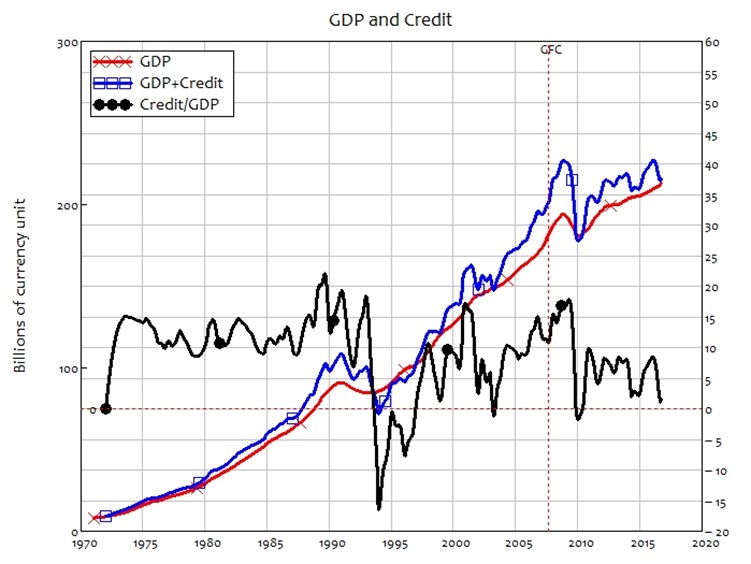

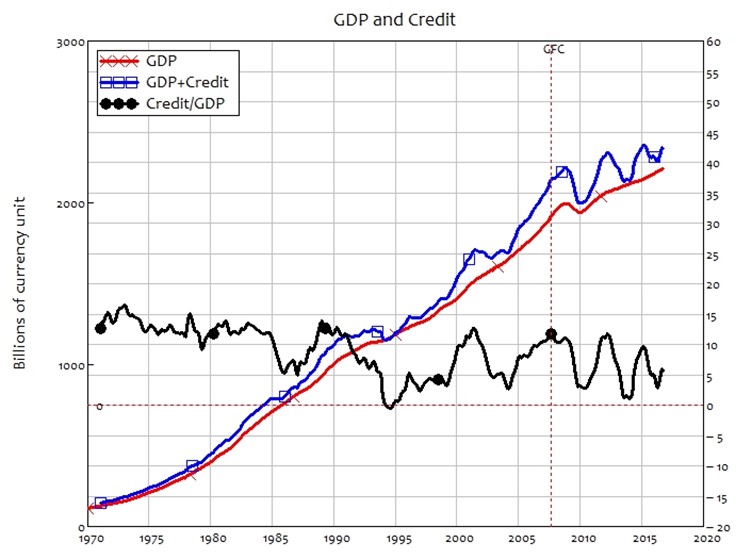

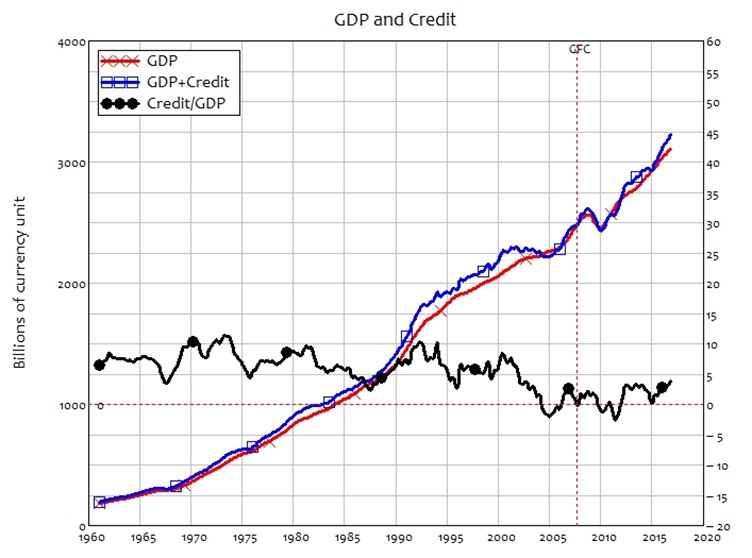

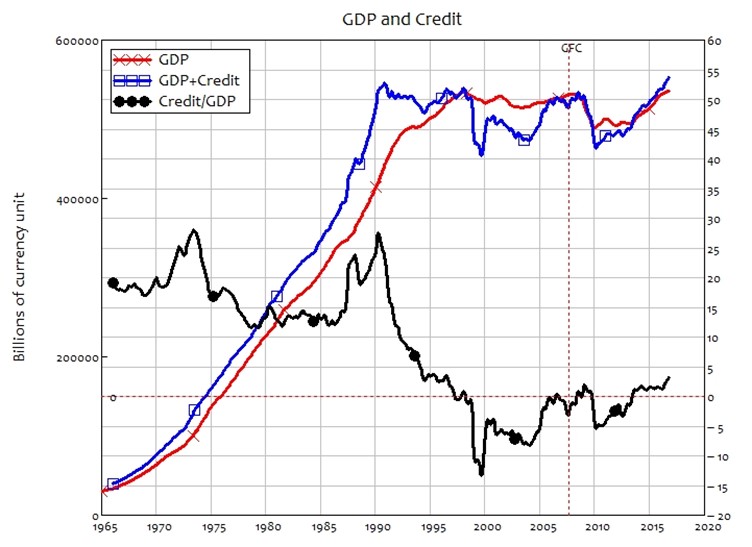

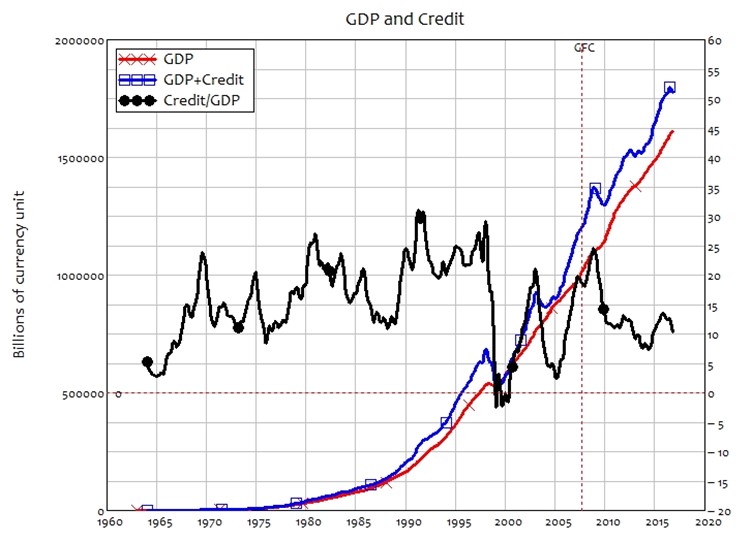

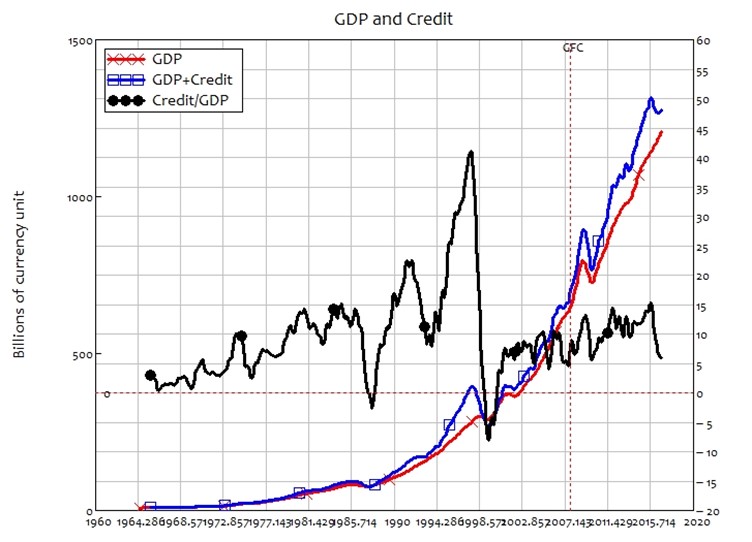

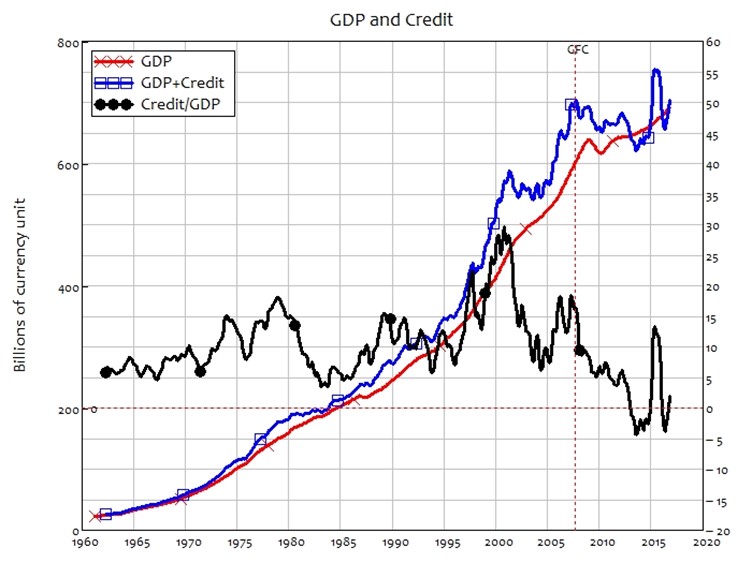

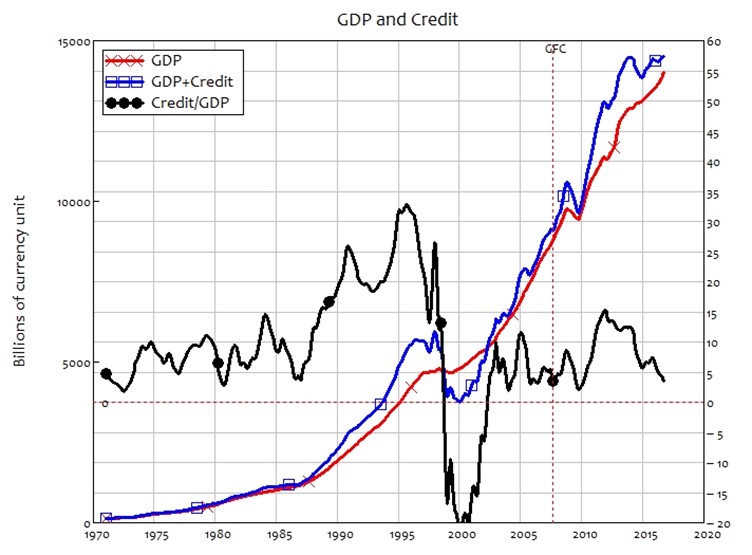

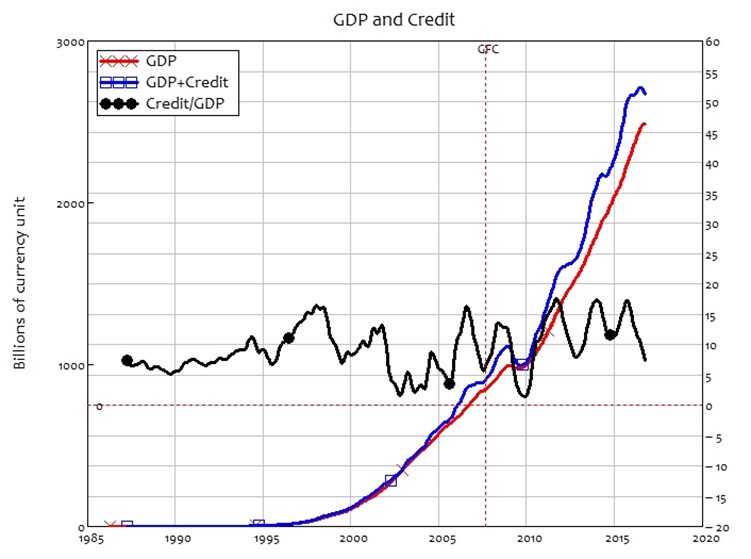

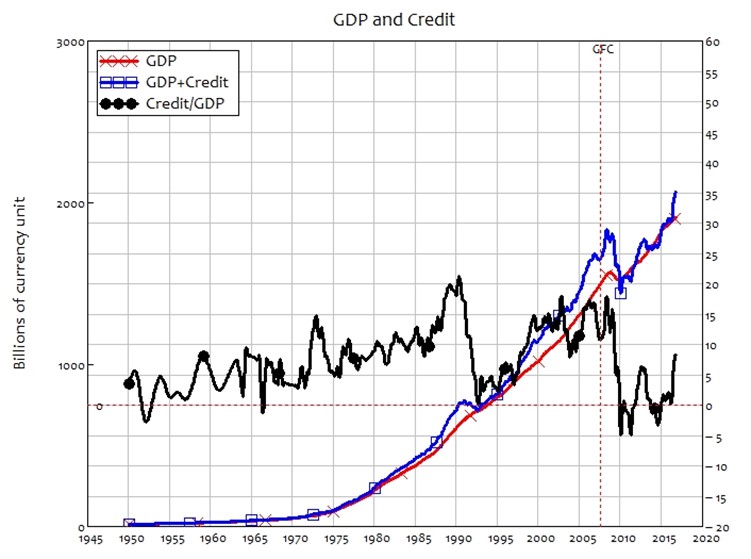

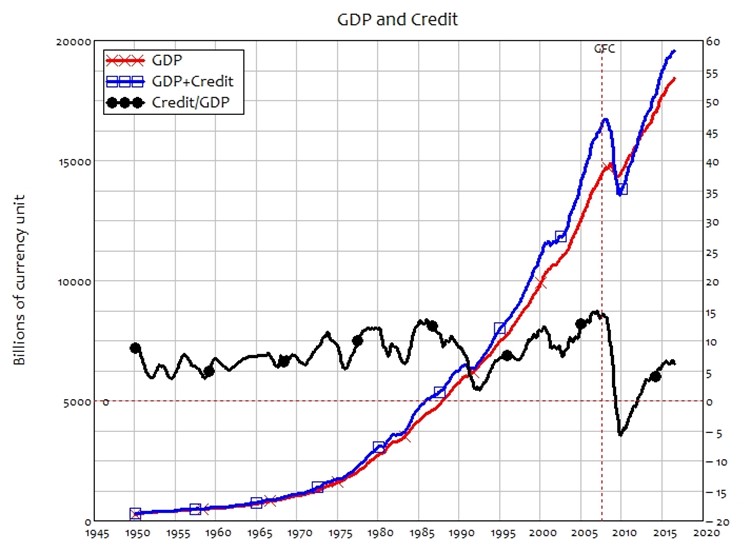

It has always been easy to find data on government debt, because mainstream economic theory, via concepts like “Ricardian Equivalence” (Barro 1973, Barro 1978, Barro 1989, Barro 1991), has argued that this is an important economic variable, and economic statisticians collect the data that economists assert is significant. Private debt data, on the other hand, was available only by historical accident—as in the case of the US Federal Reserve’s Flow of Funds data, which was designed in the early post-WWII period before concepts like Ricardian Equivalence raised their misleading heads—because mainstream economists argued that private debt was a “pure redistribution” and, to quote Ben Bernanke, “Absent implausibly large differences in marginal spending propensities among the groups, … pure redistributions should have no significant macro¬economic effects” (Bernanke 2000, p. 24)

That changed in 2014, when the Bank of International Settlements released a database on private debt. The BIS stepped outside the mainstream because it had the good fortune to have, in Bill White, a Research Director who took Hyman Minsky’s “Financial Instability Hypothesis” seriously (Minsky 1963, Minsky 1977, Minsky 1978, Minsky 1982, Minsky 1982), when mainstream economists simply ignored him. Bill White has since moved to the OECD, but the tradition he established at the BIS lives on.

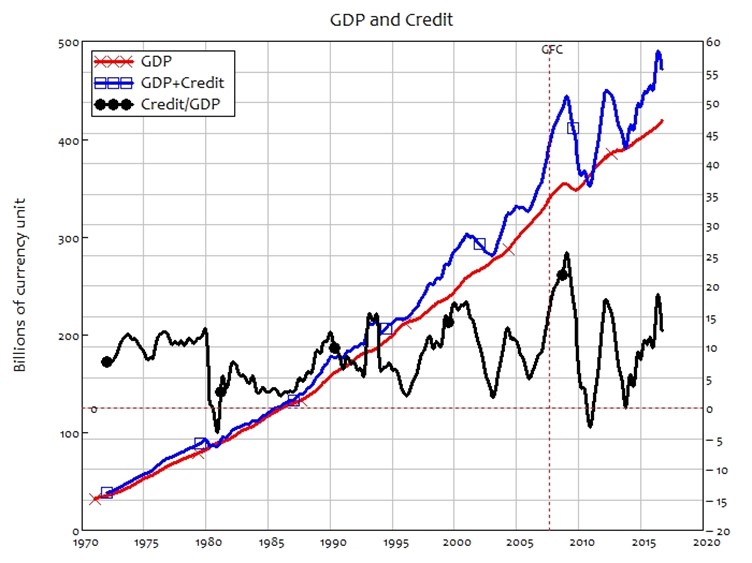

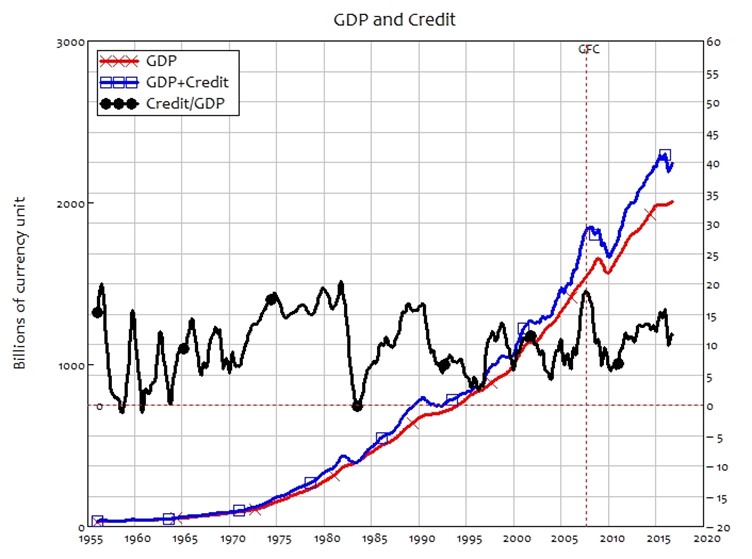

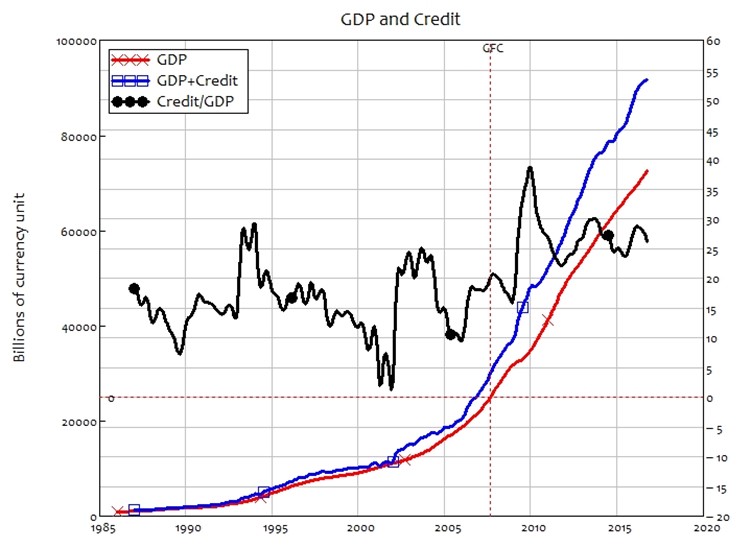

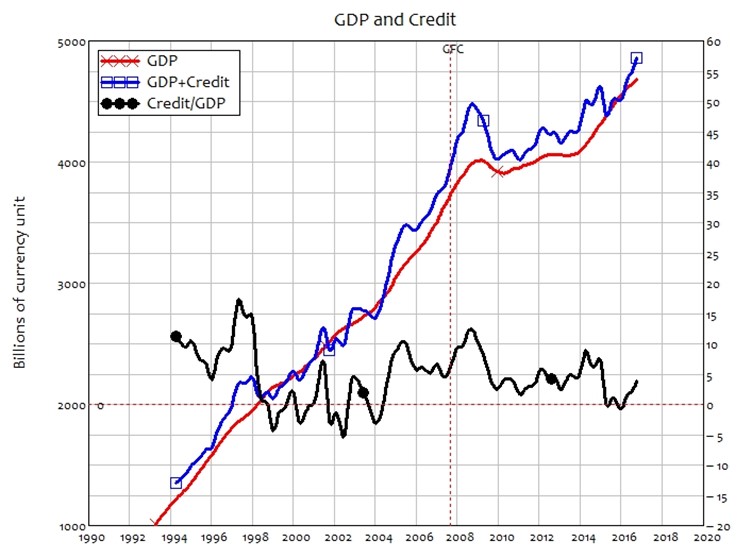

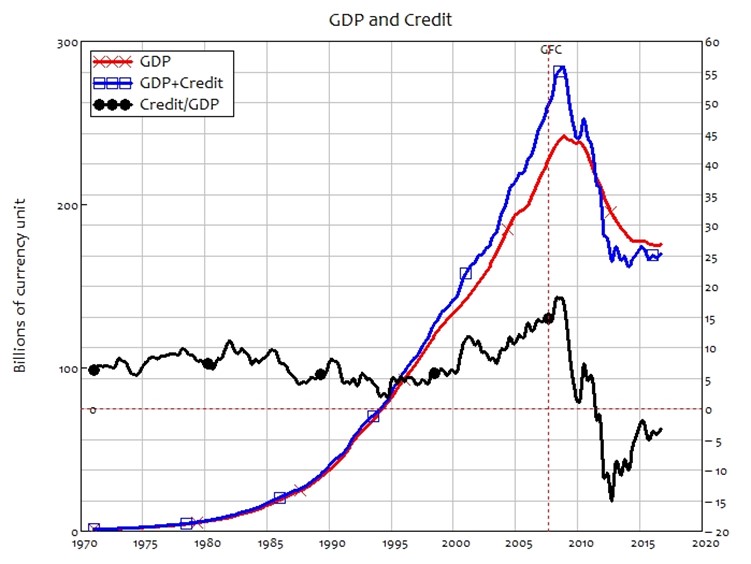

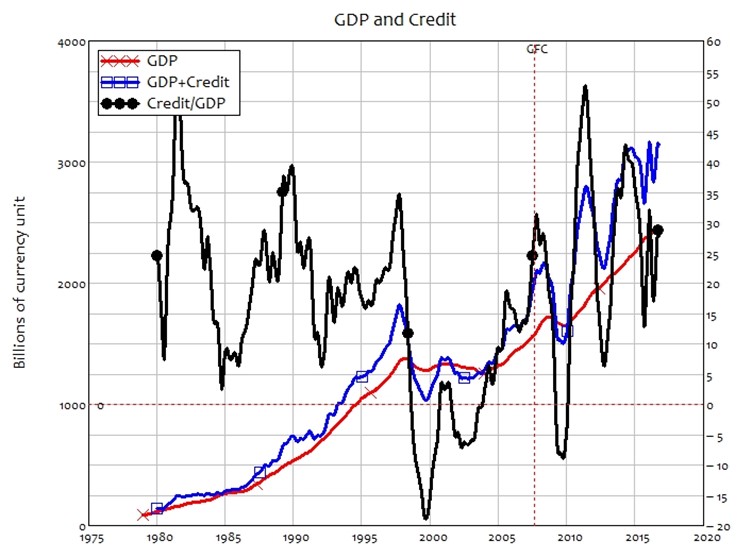

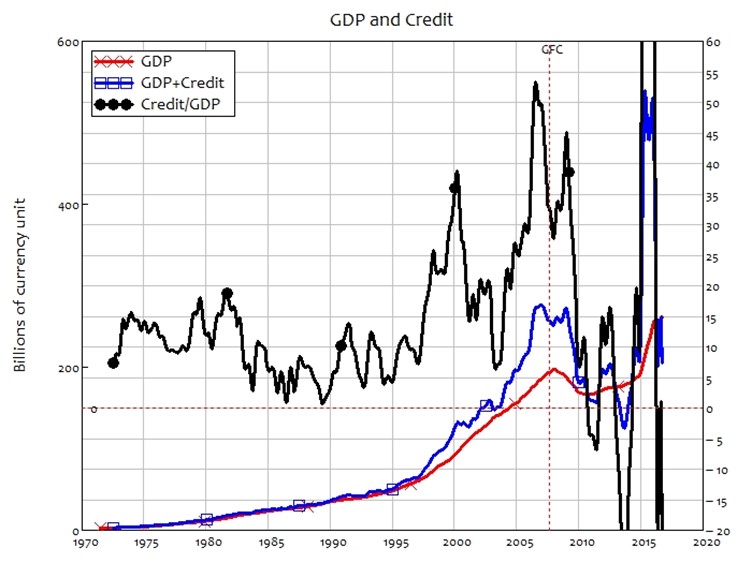

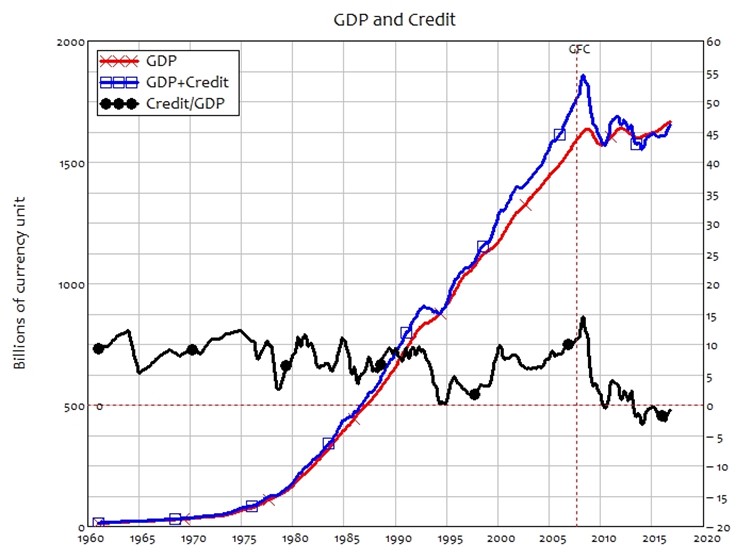

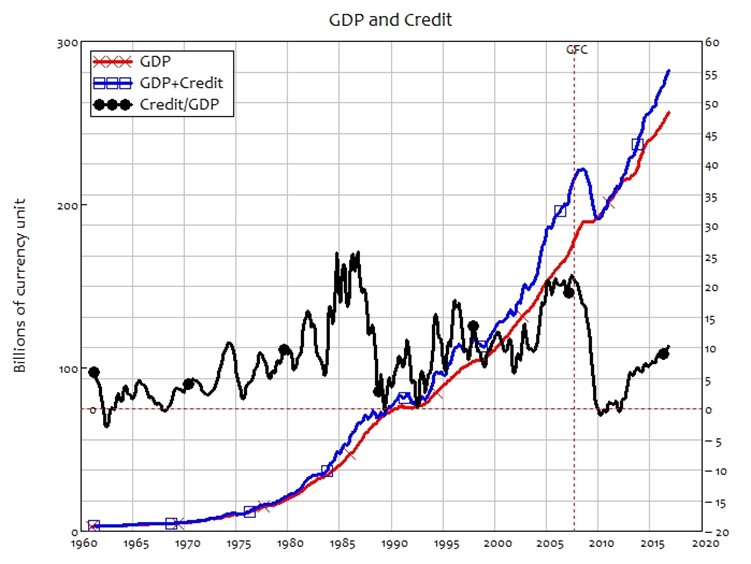

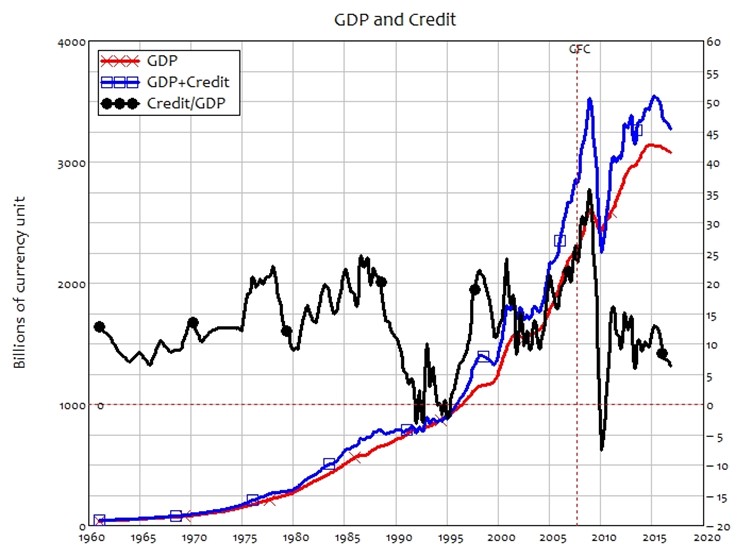

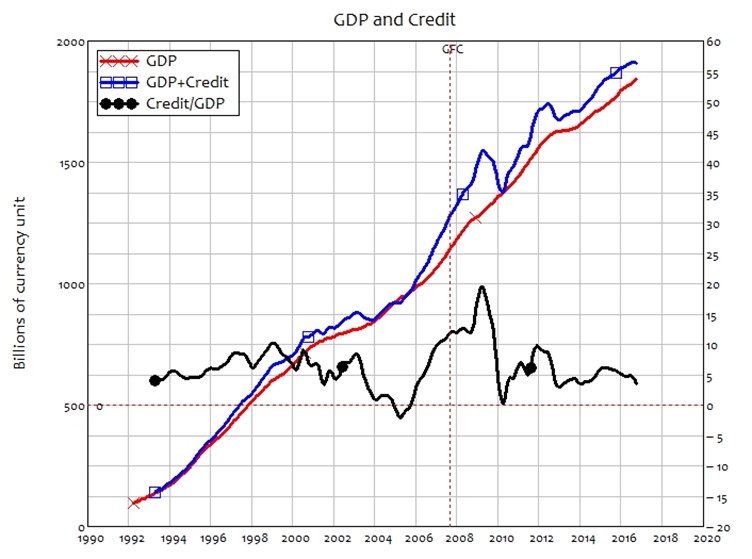

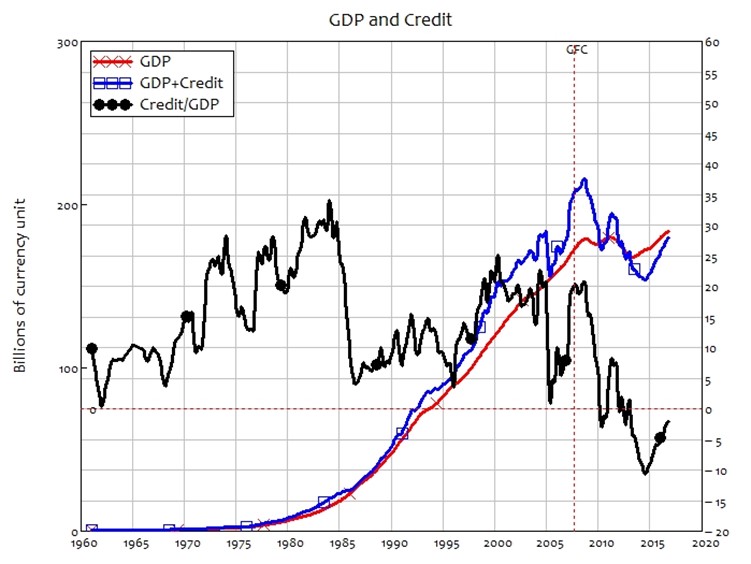

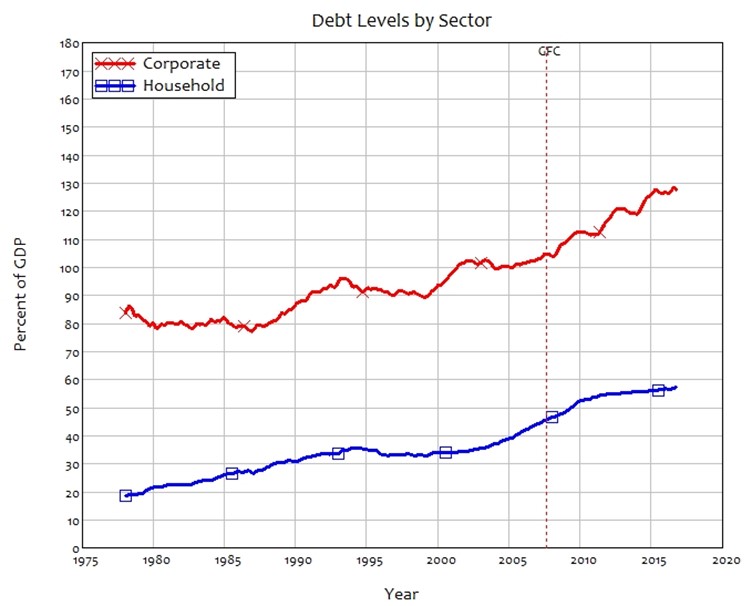

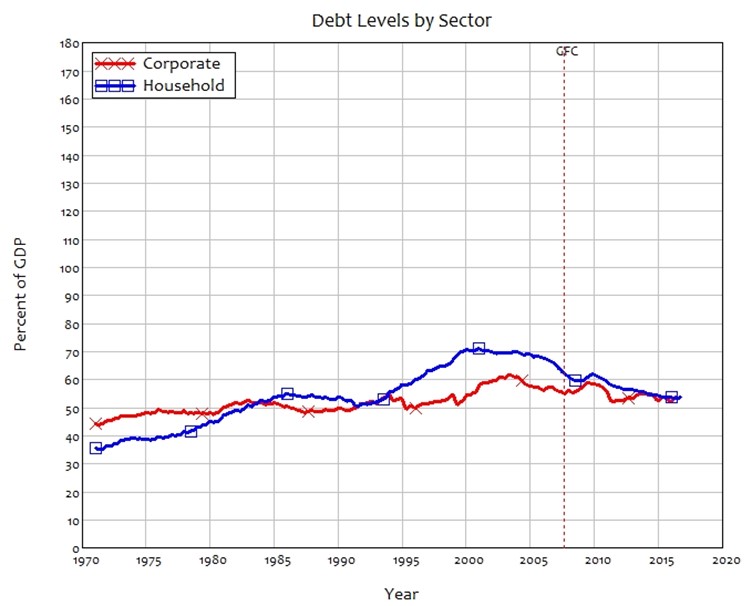

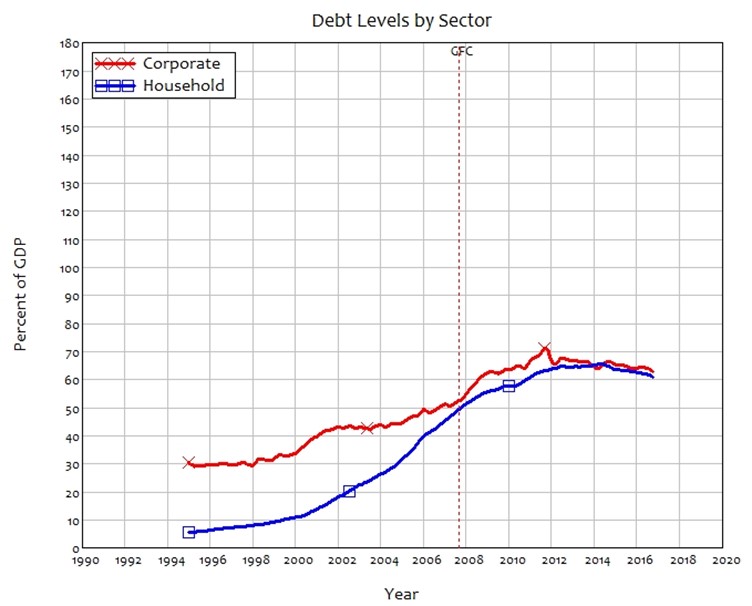

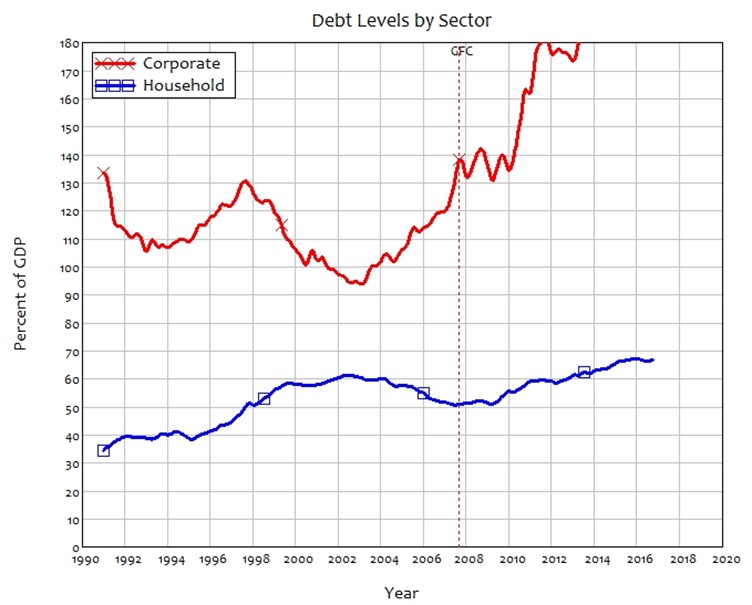

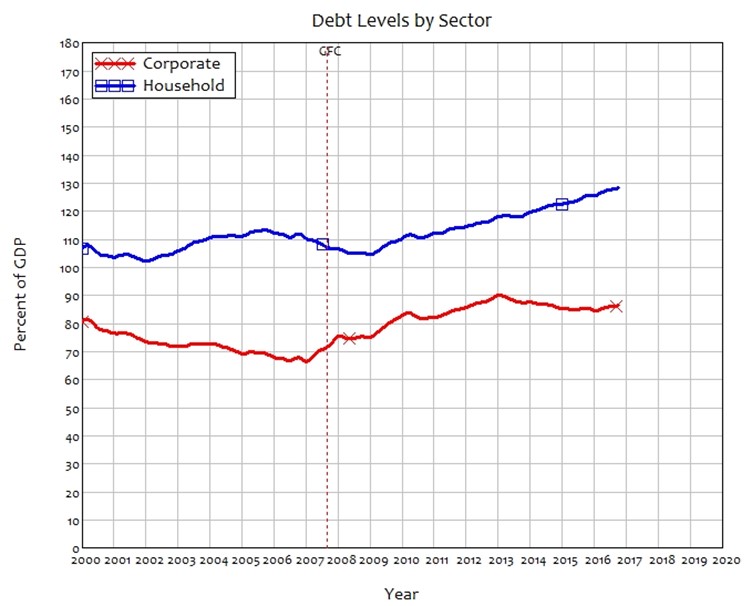

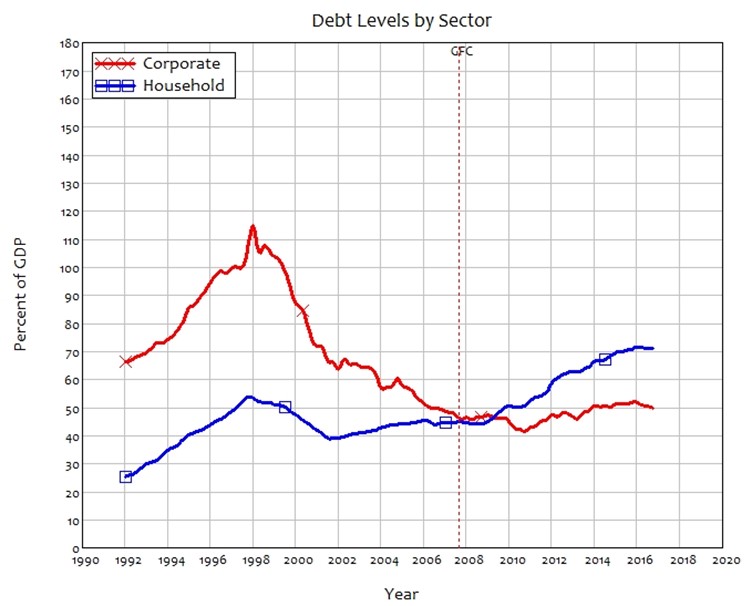

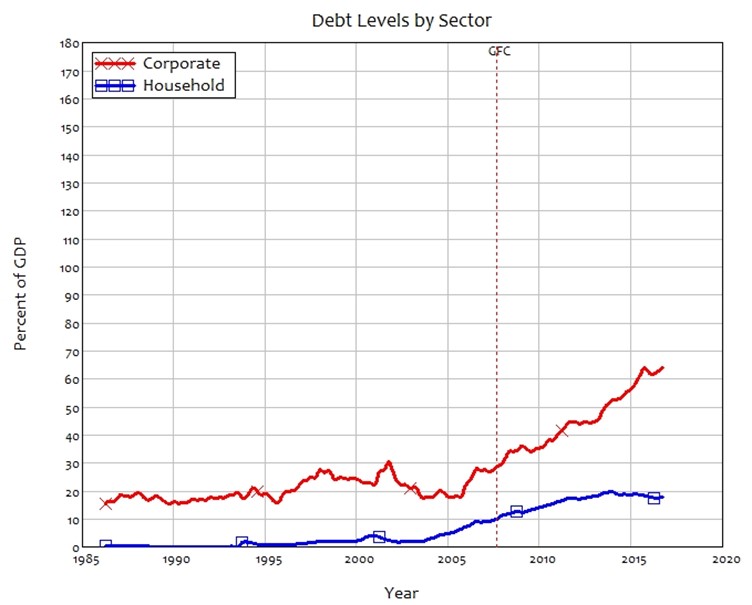

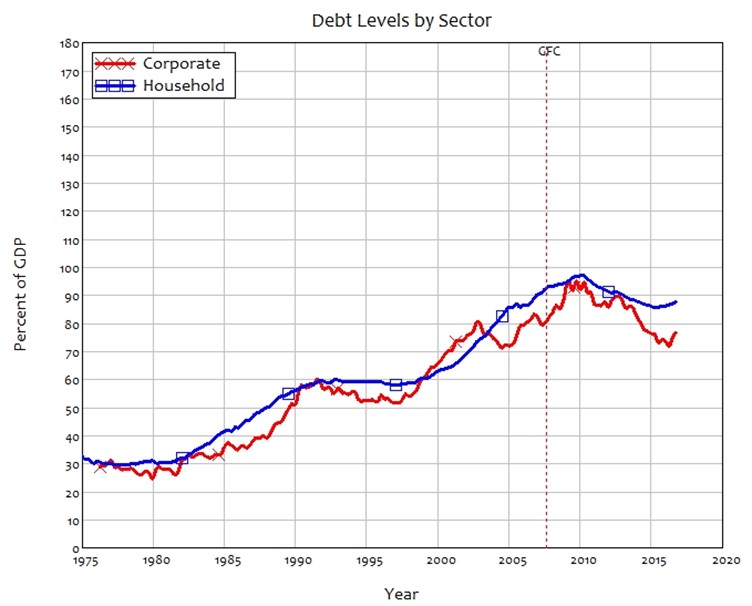

That data made this book possible. But the size of the book—a mere 25,000 words—made putting all the data in the book impossible. Thankfully the web enables a way around this. While I focused on the data for just the USA, UK, Australia, Japan and China in the book, this web page provides all the data for all countries in the BIS databases—which now include house prices and consumer prices.

The charts here are static snapshots of the data as of Q3 2016, but in a short while I will release Ravel©™, a new tool for dynamically presenting and analysing large data sets like this easily.

Contents

Government and Private Debt Levels 8

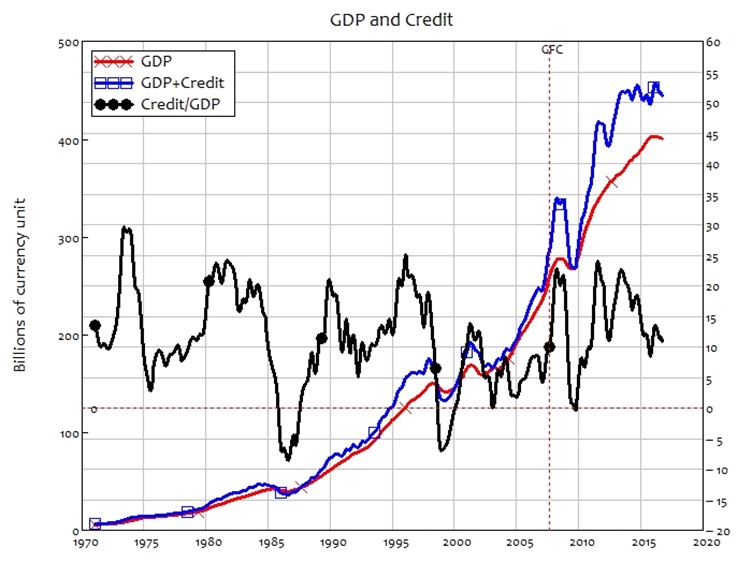

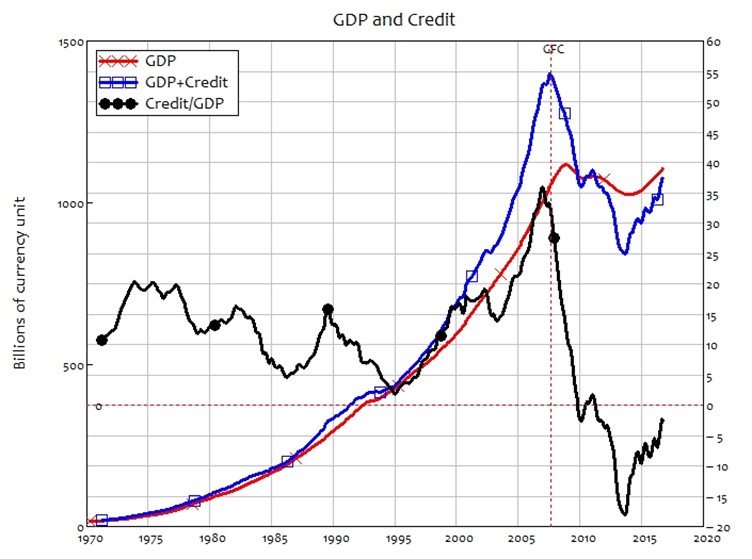

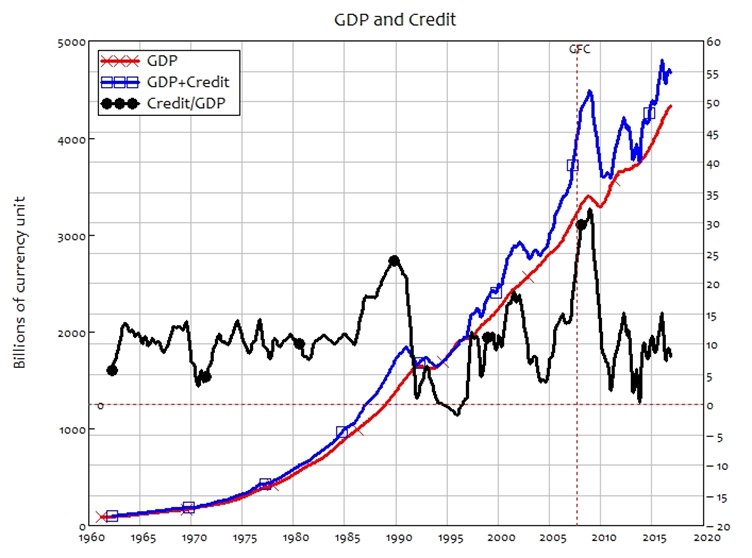

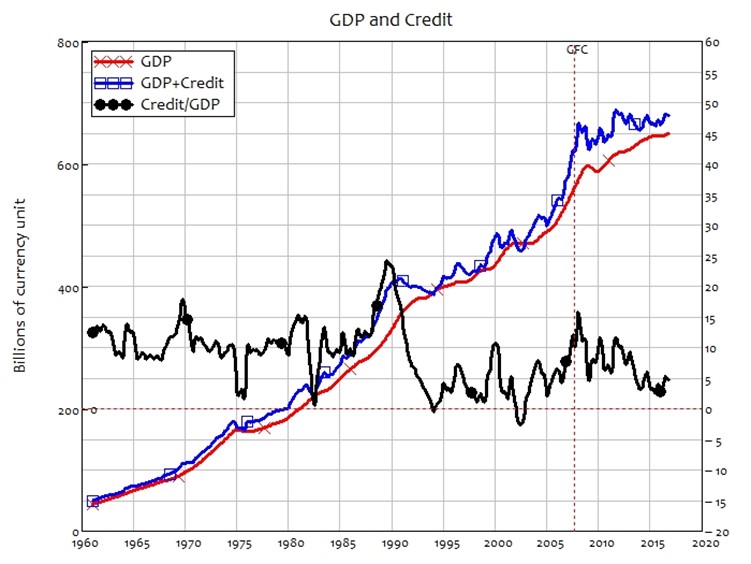

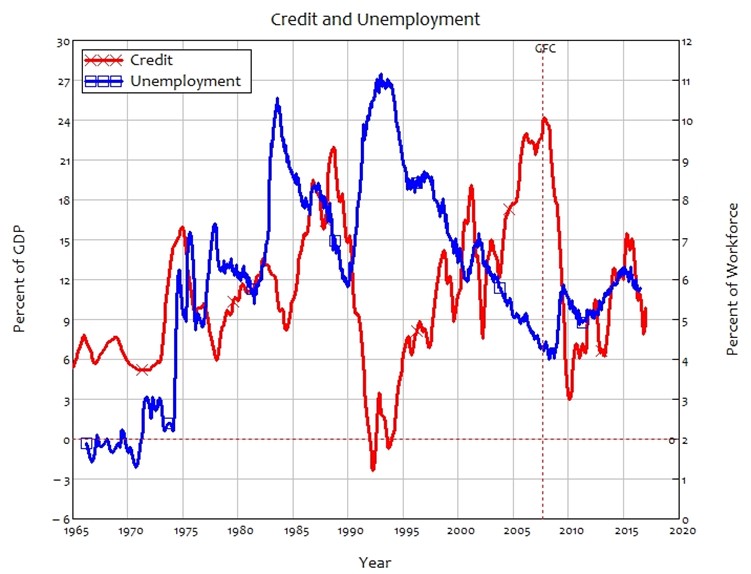

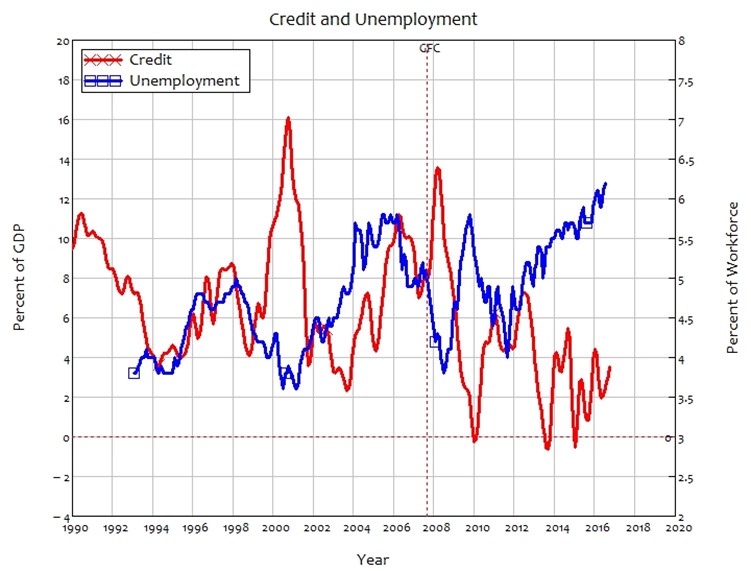

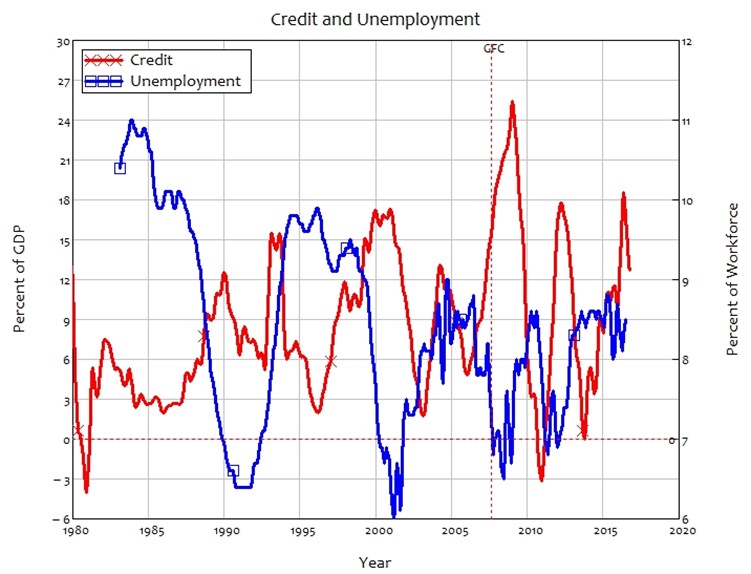

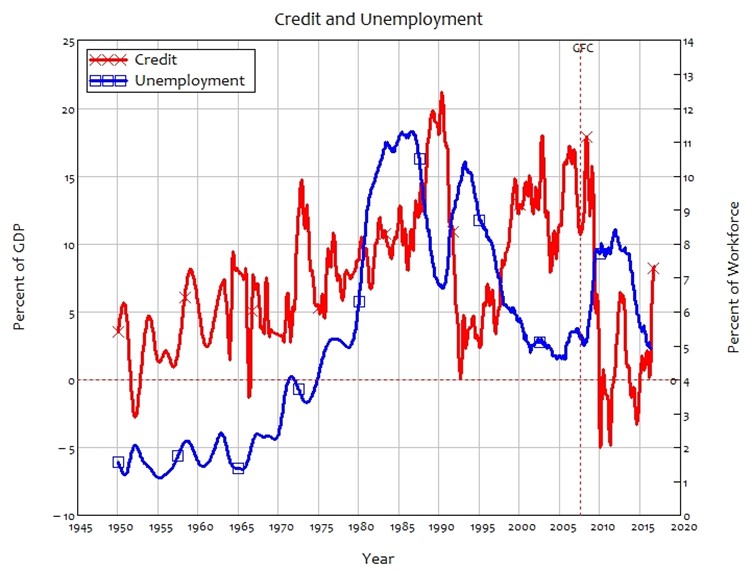

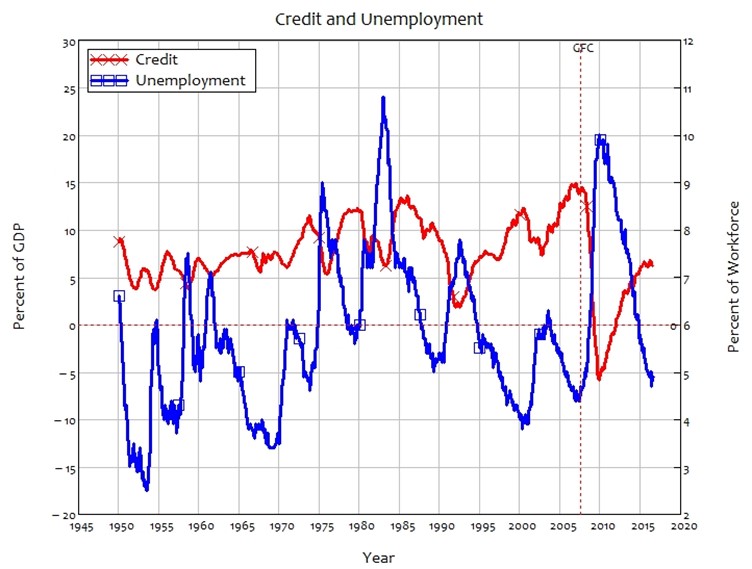

Credit and Aggregate Demand 38

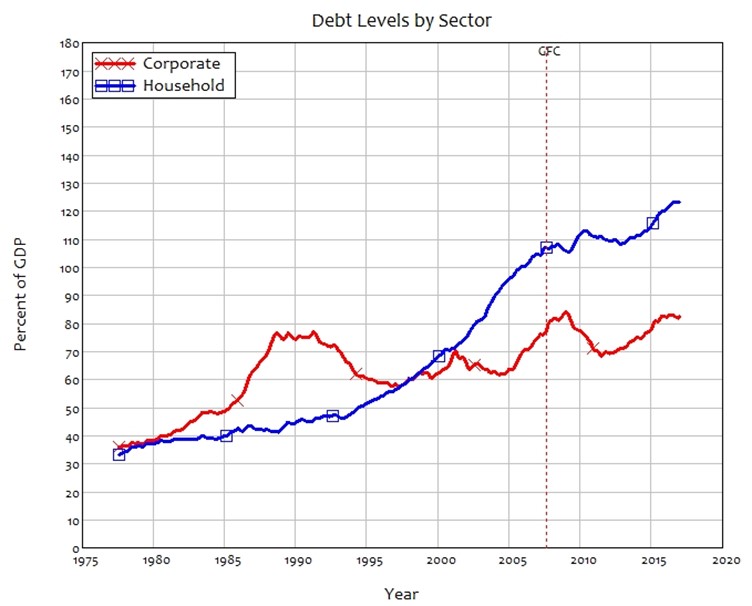

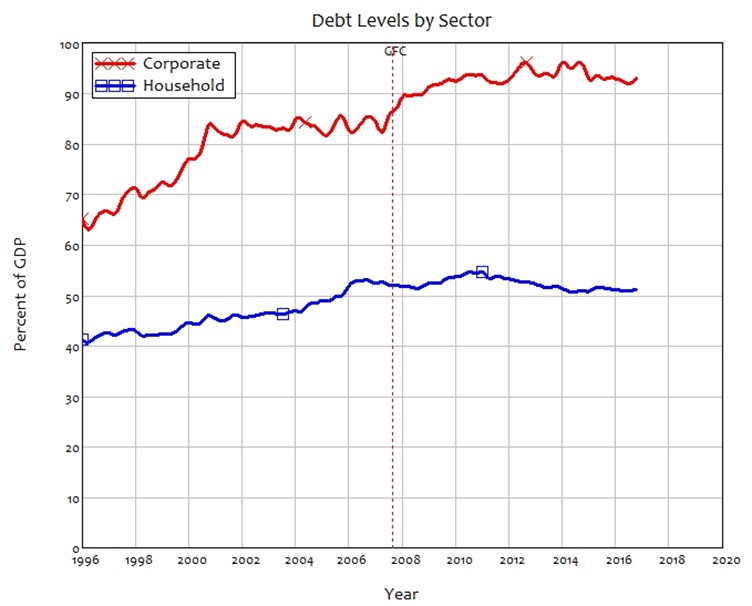

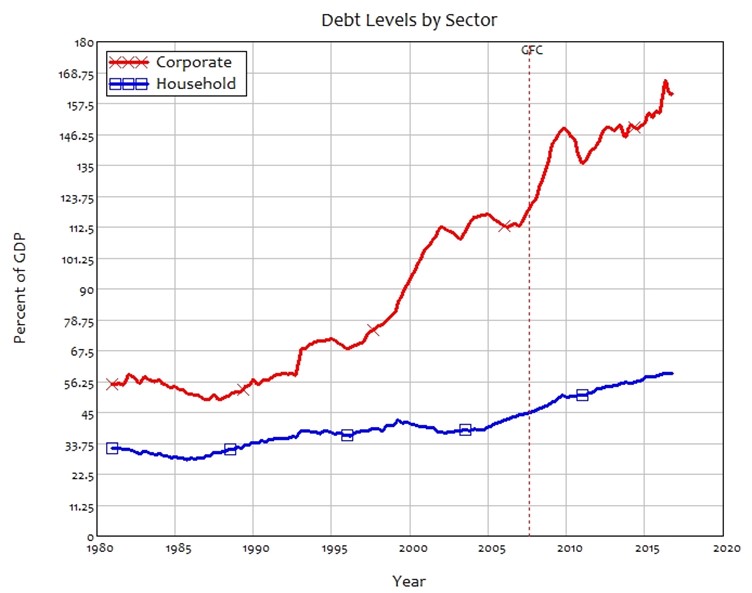

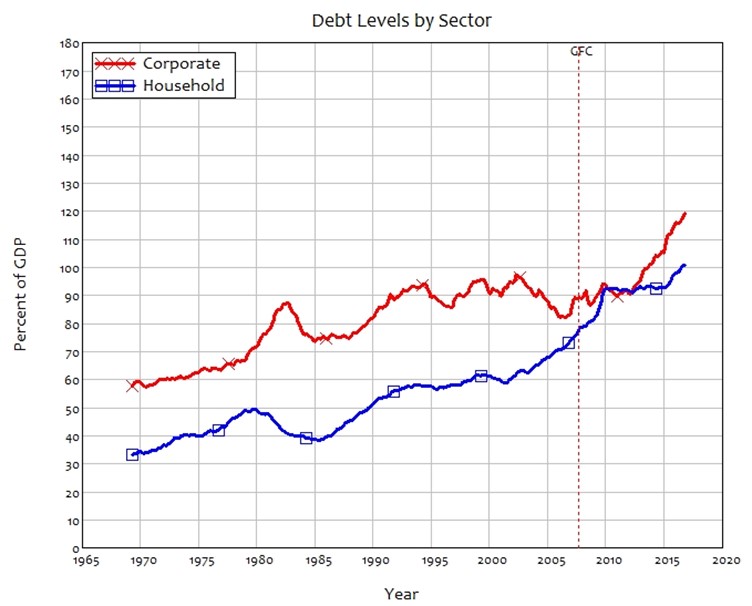

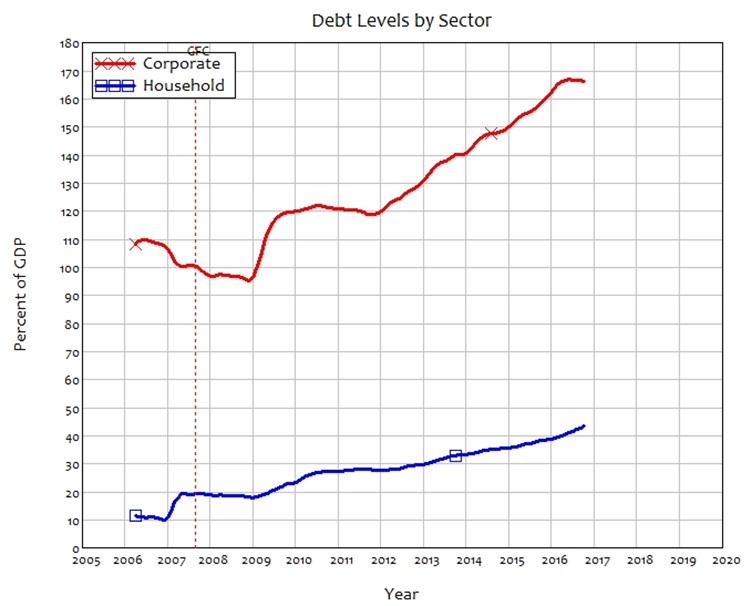

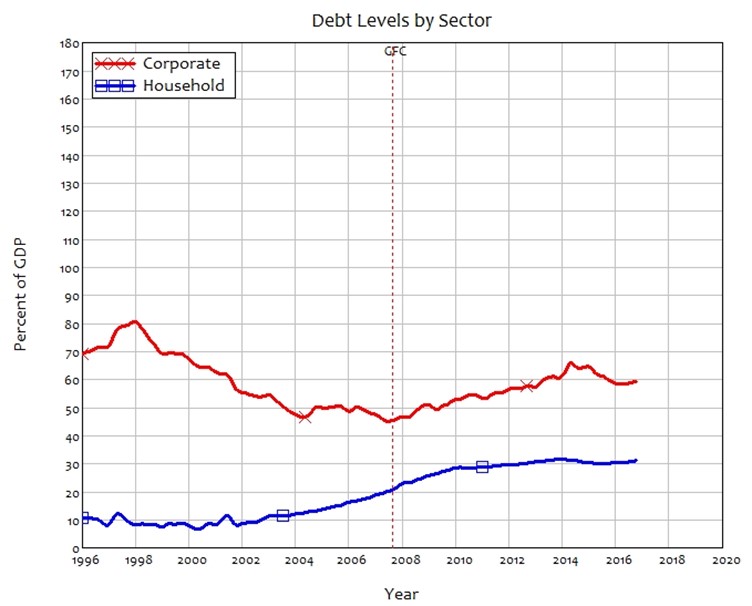

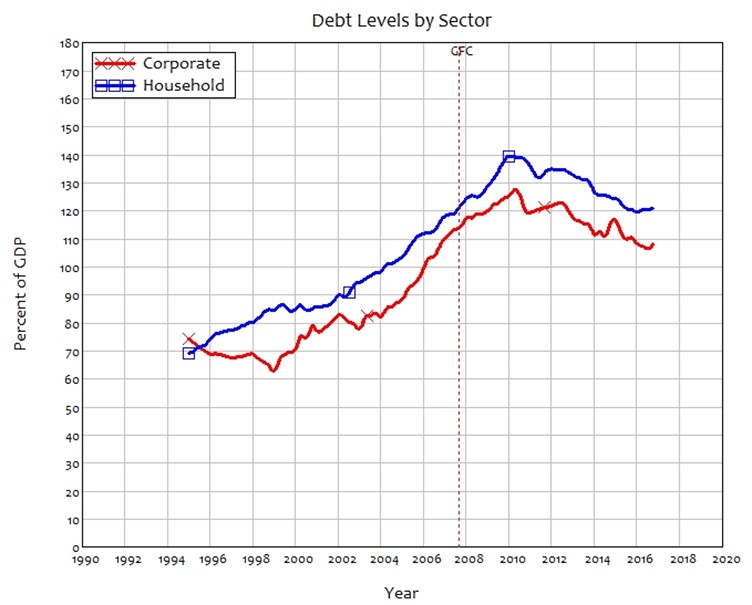

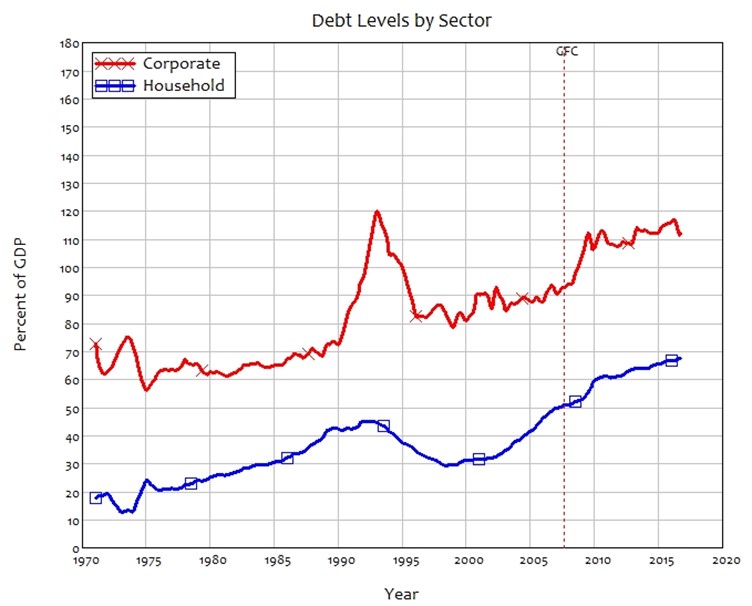

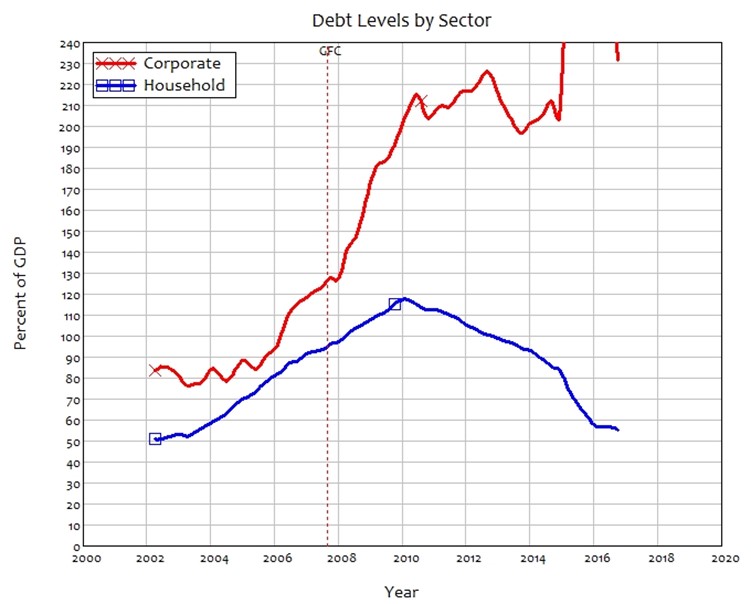

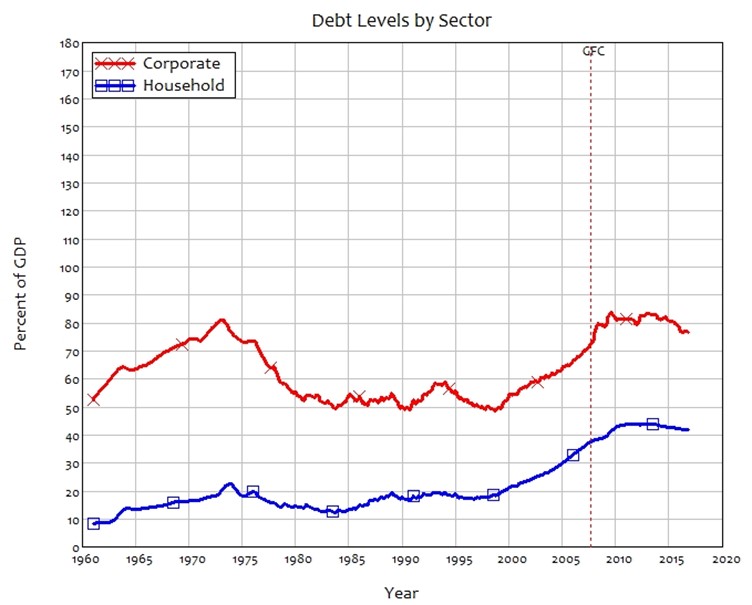

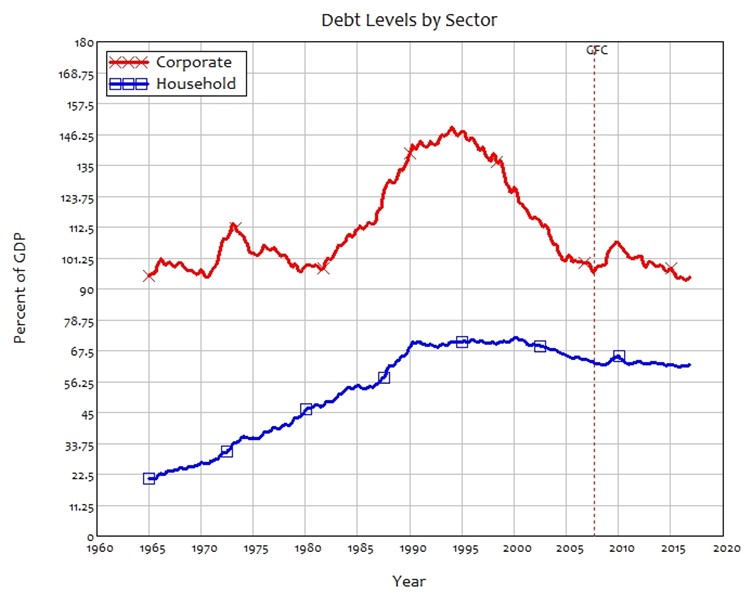

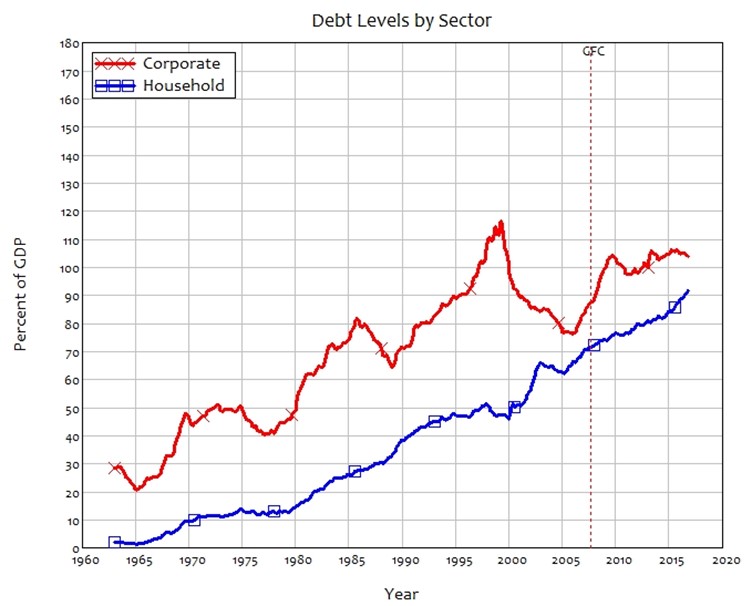

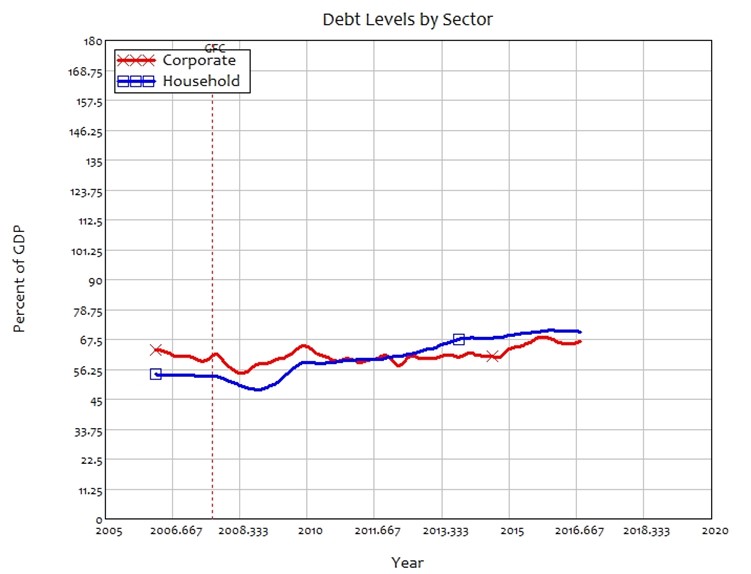

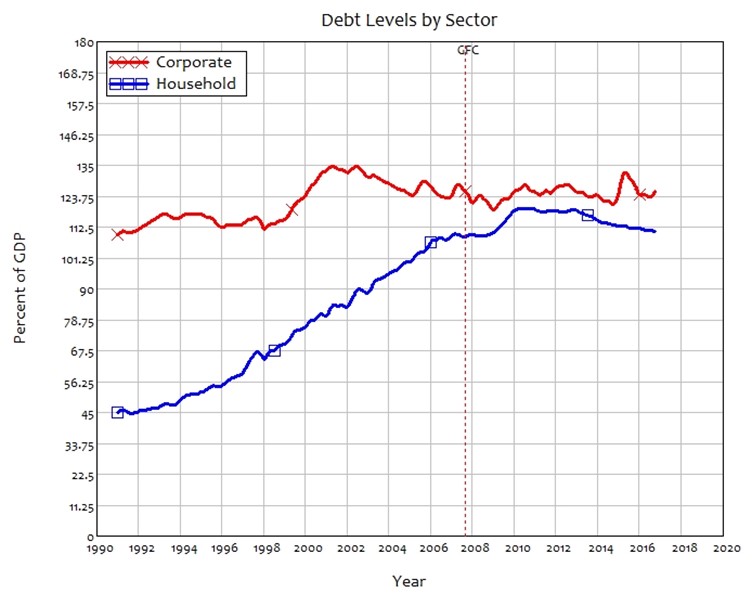

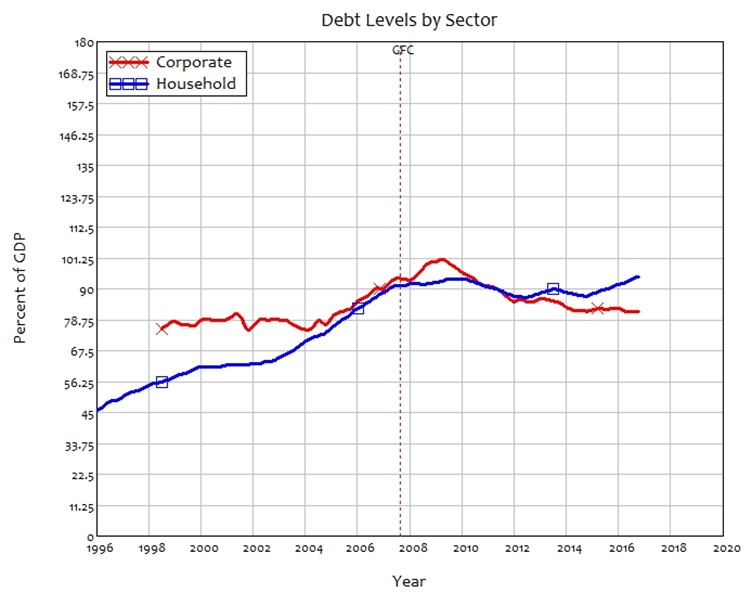

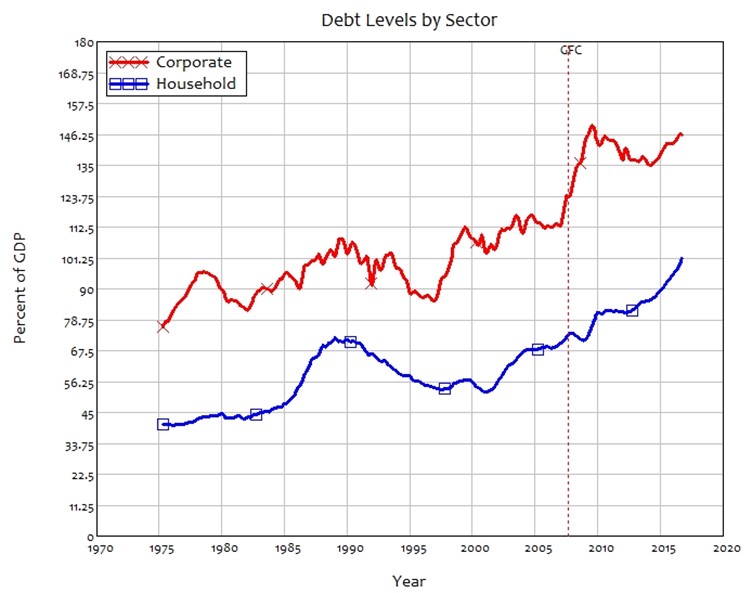

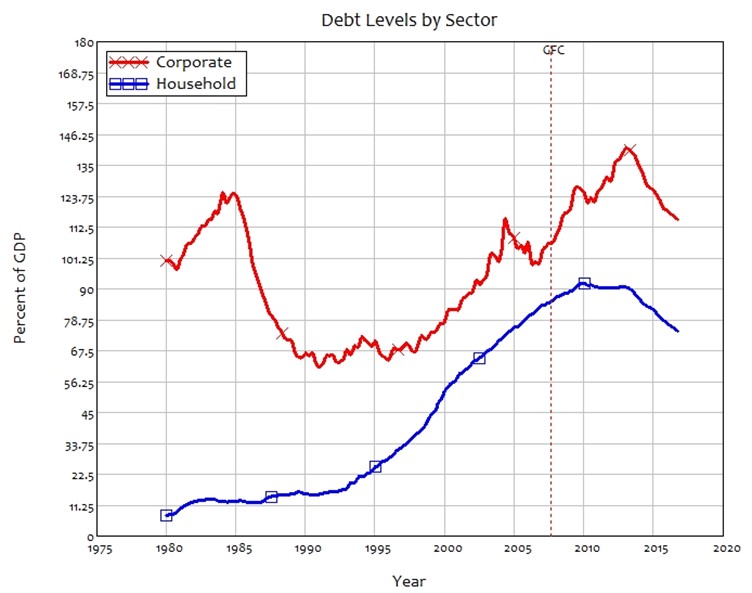

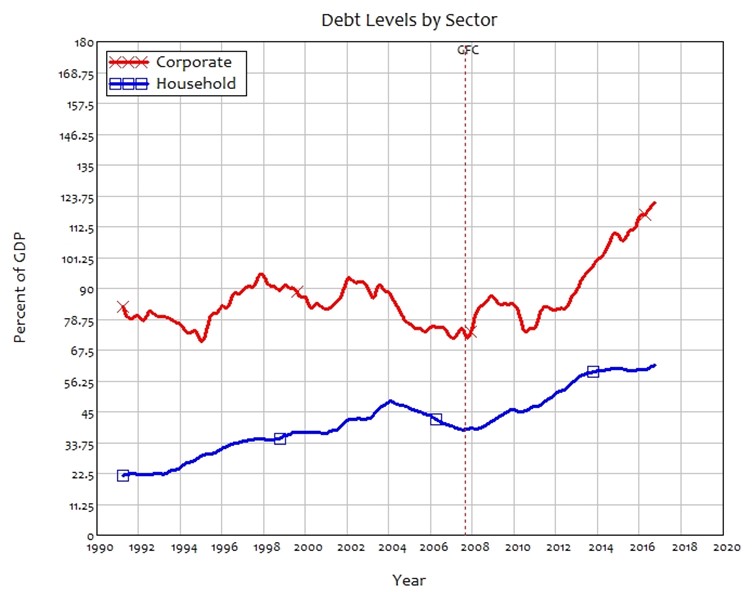

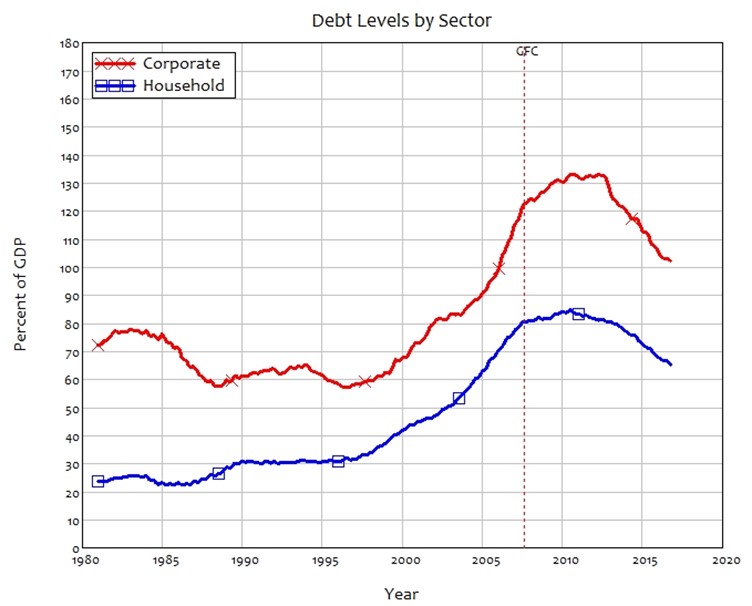

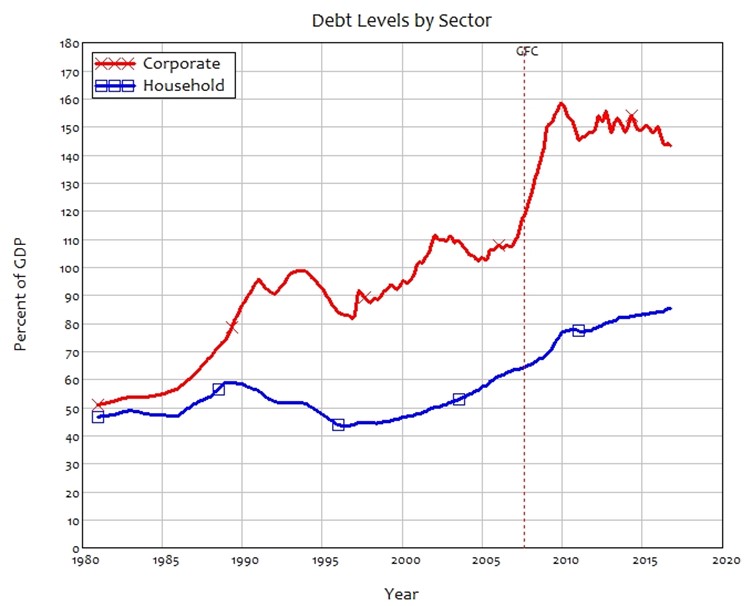

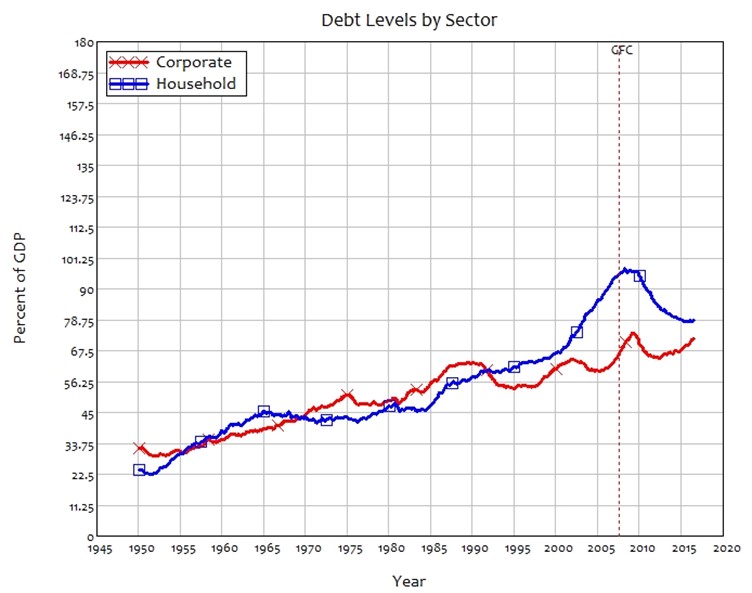

Breakdown of Private Sector Debt 68

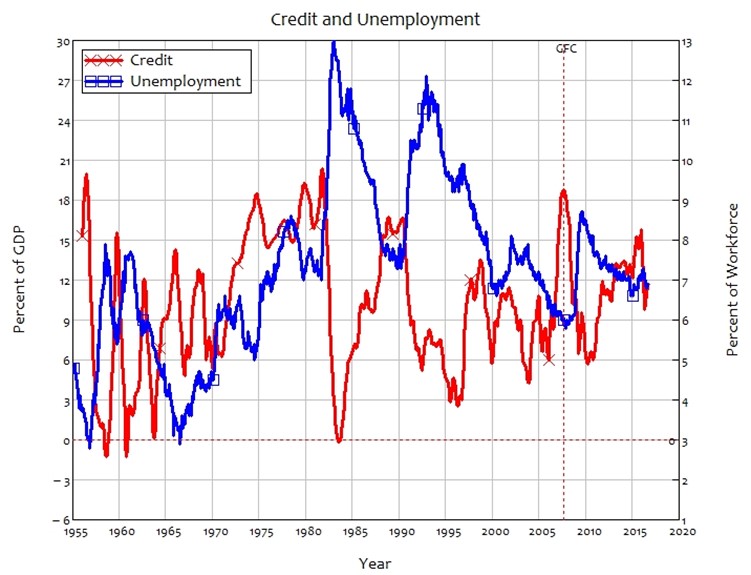

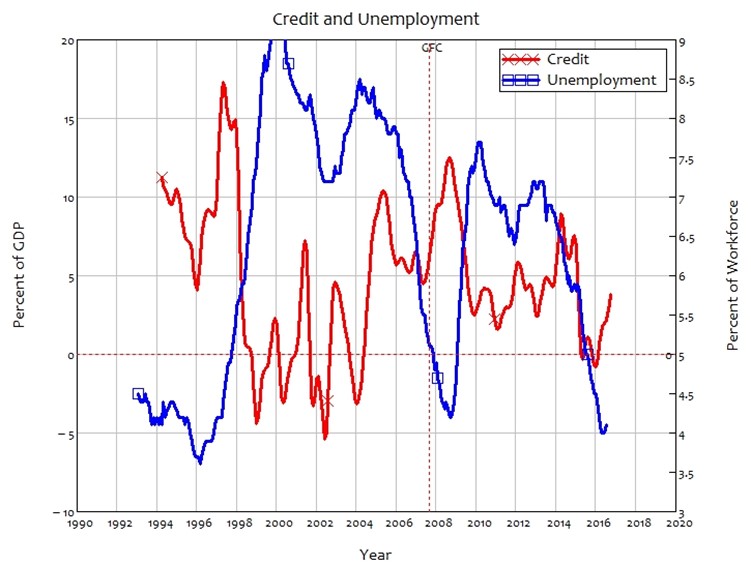

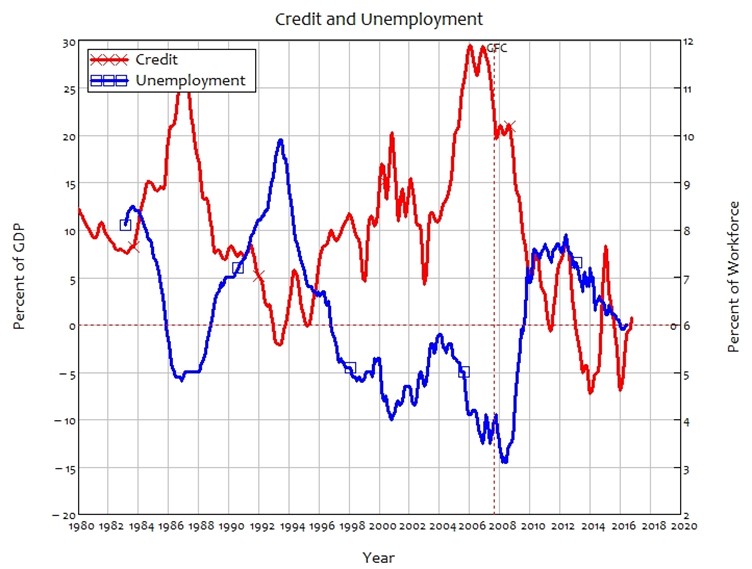

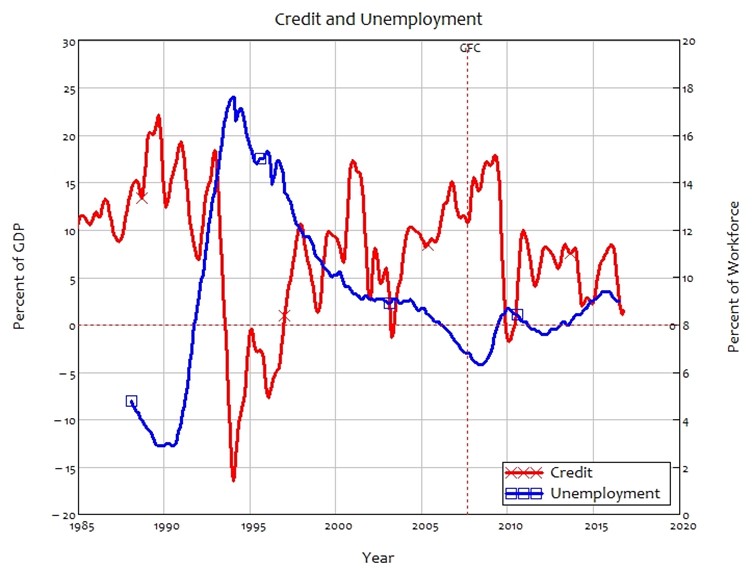

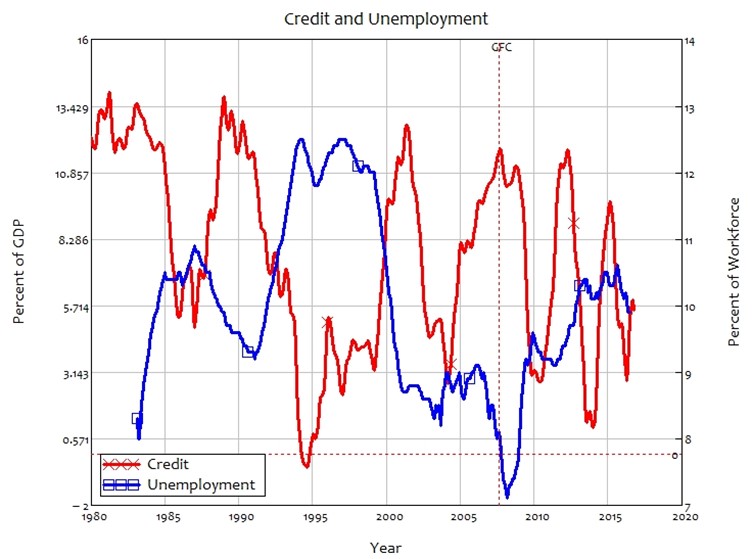

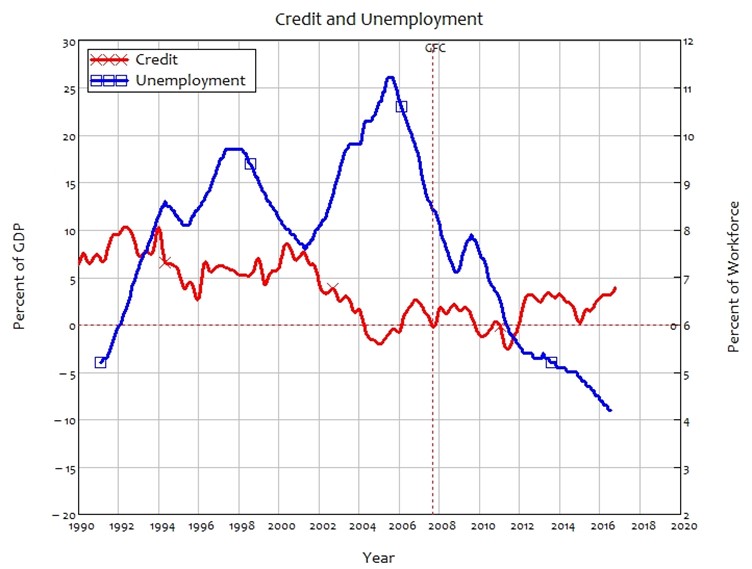

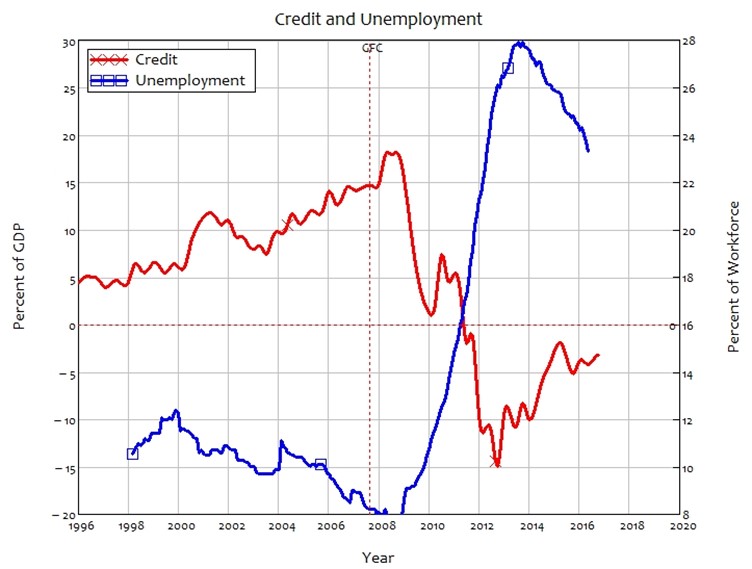

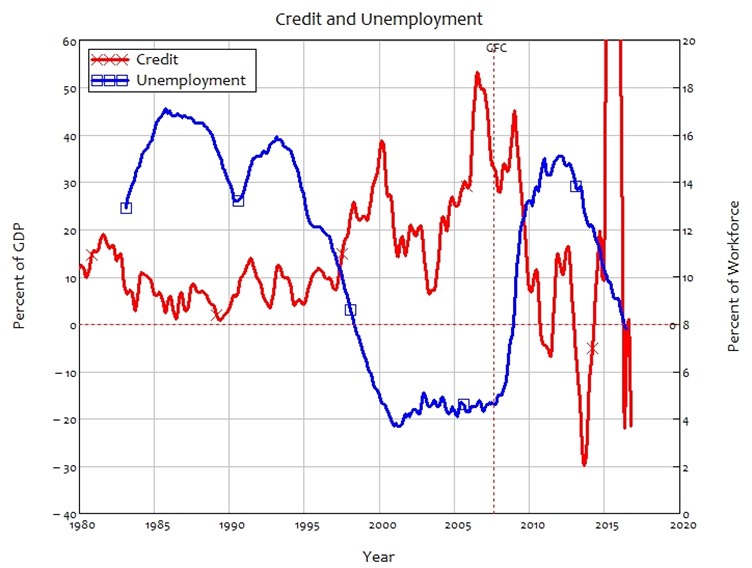

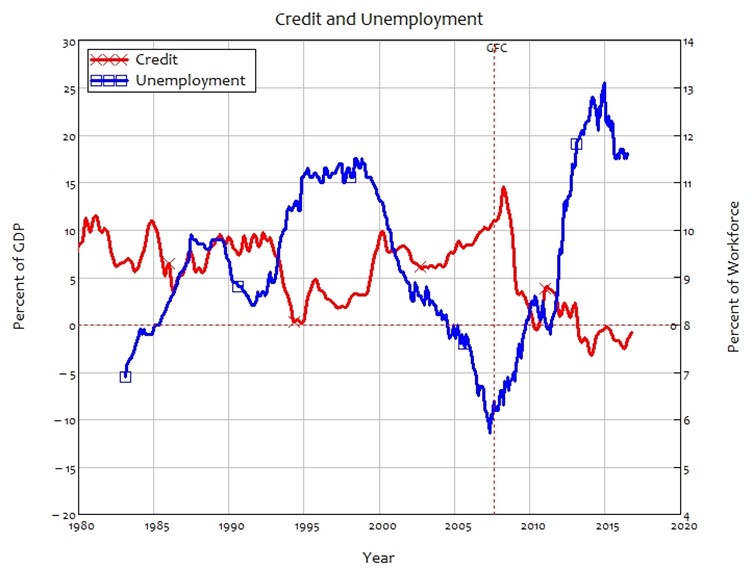

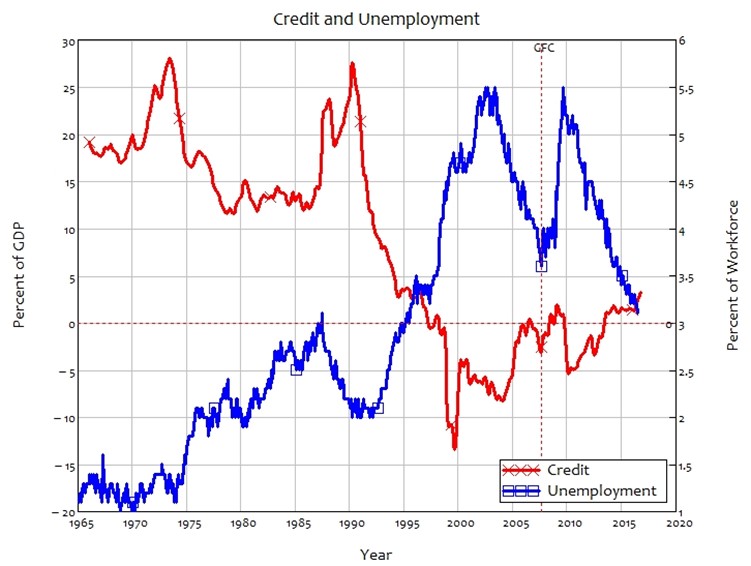

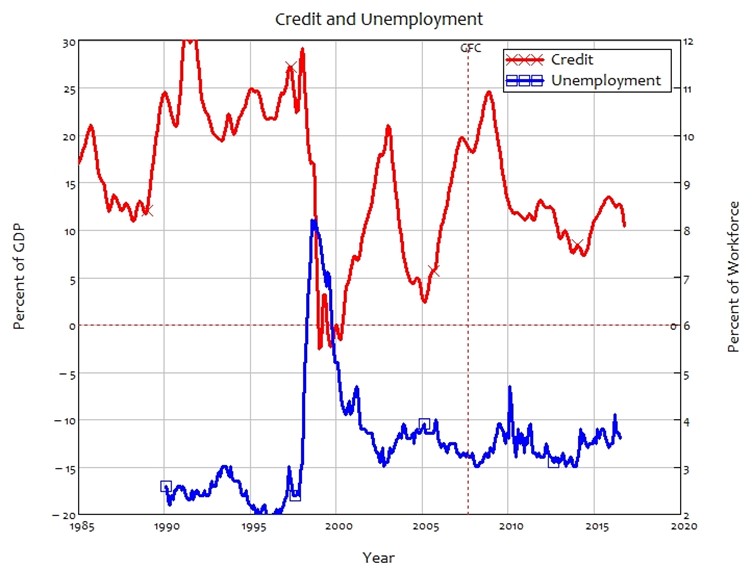

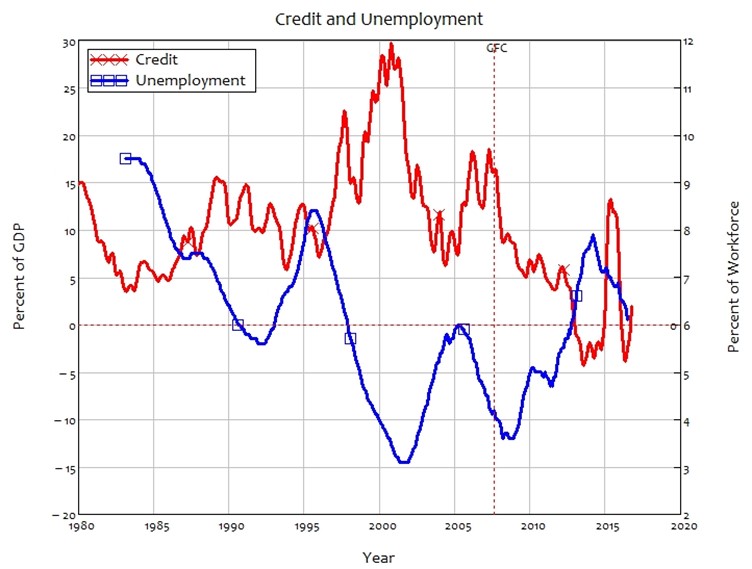

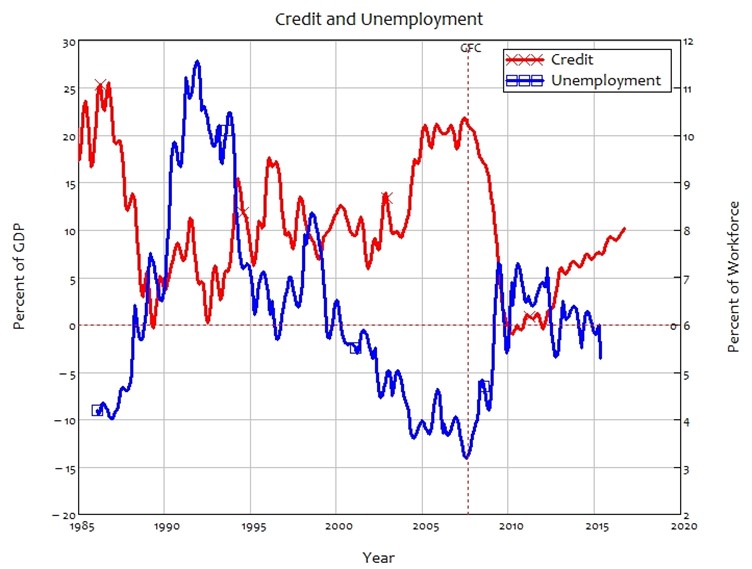

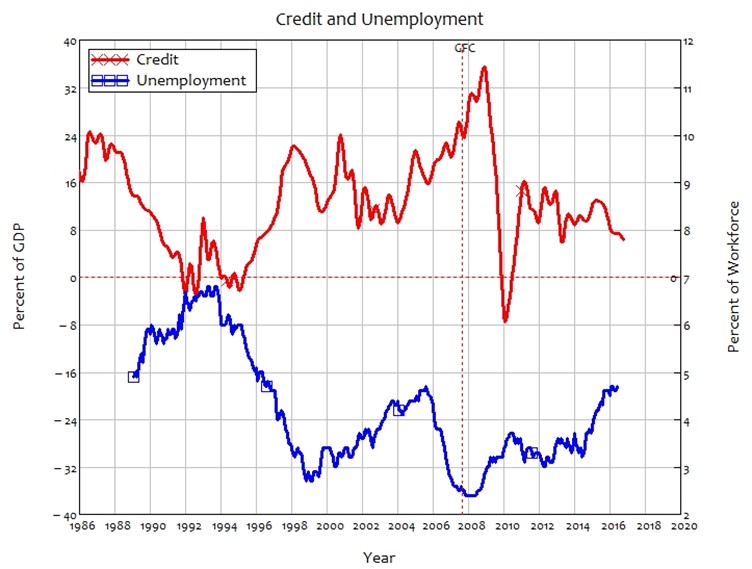

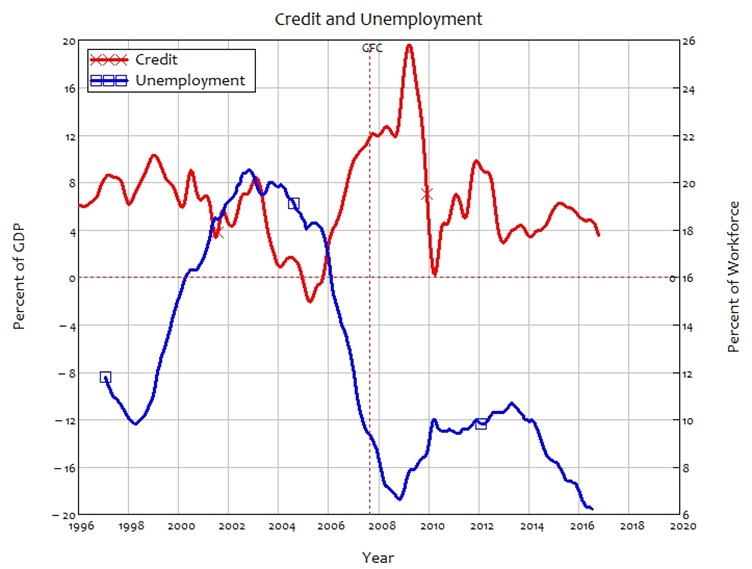

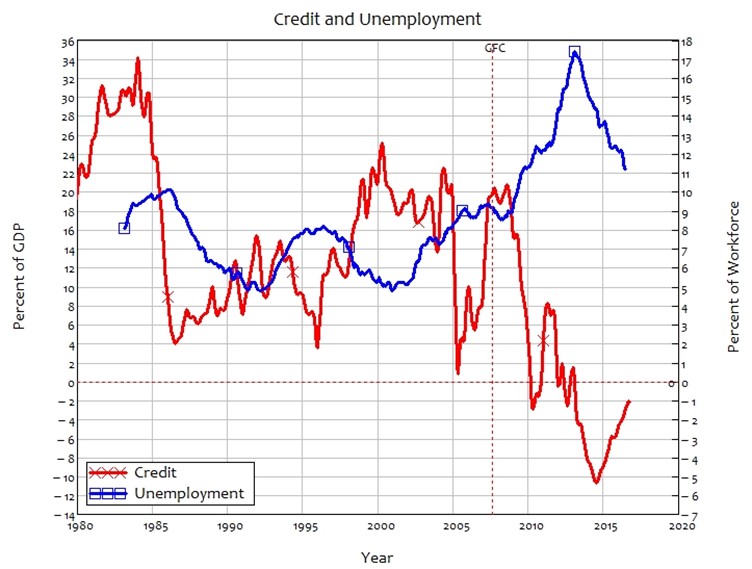

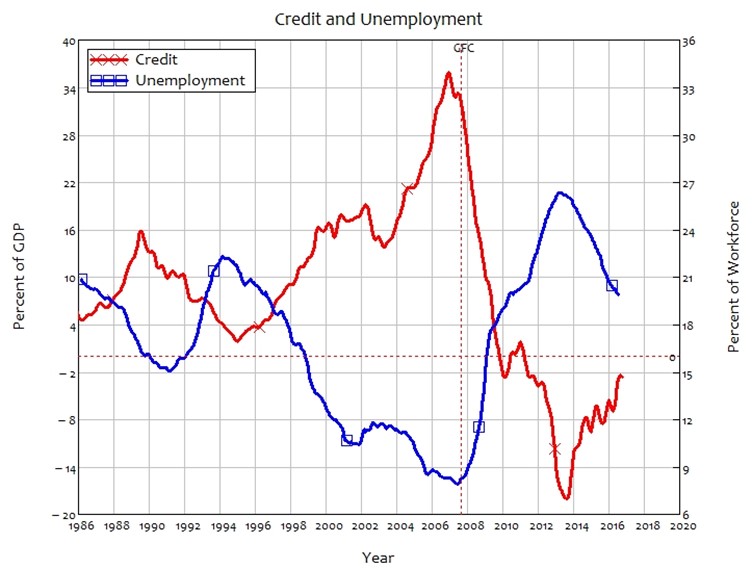

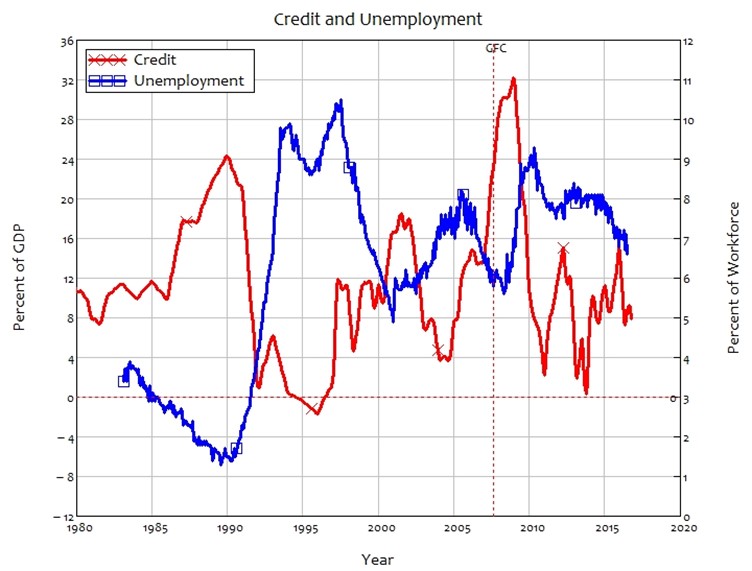

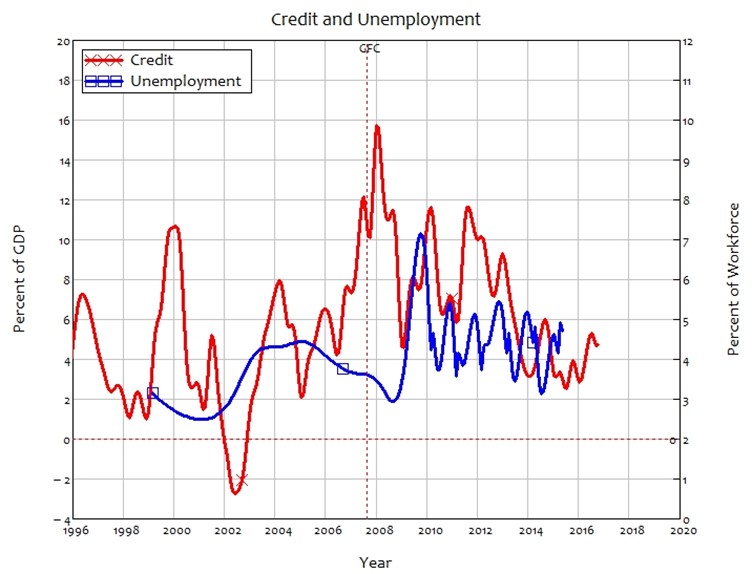

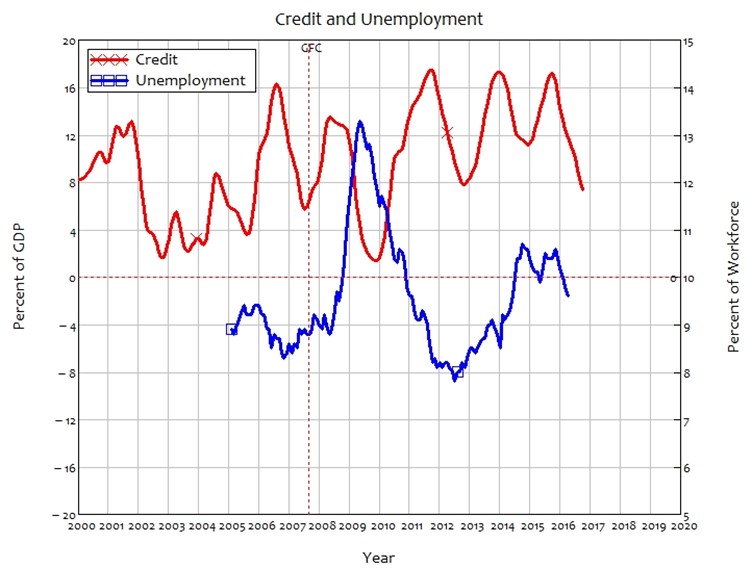

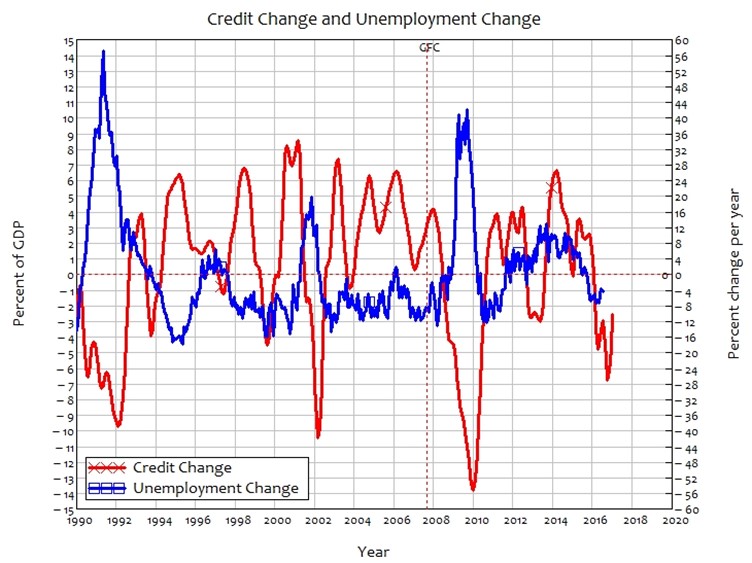

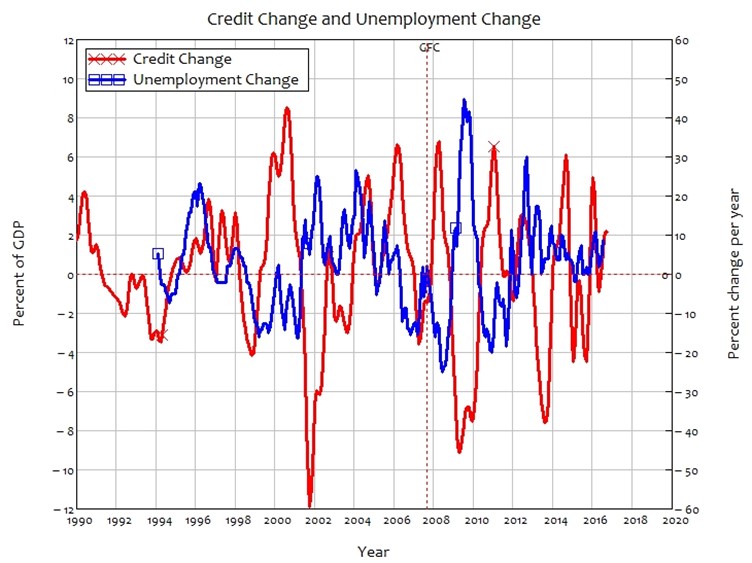

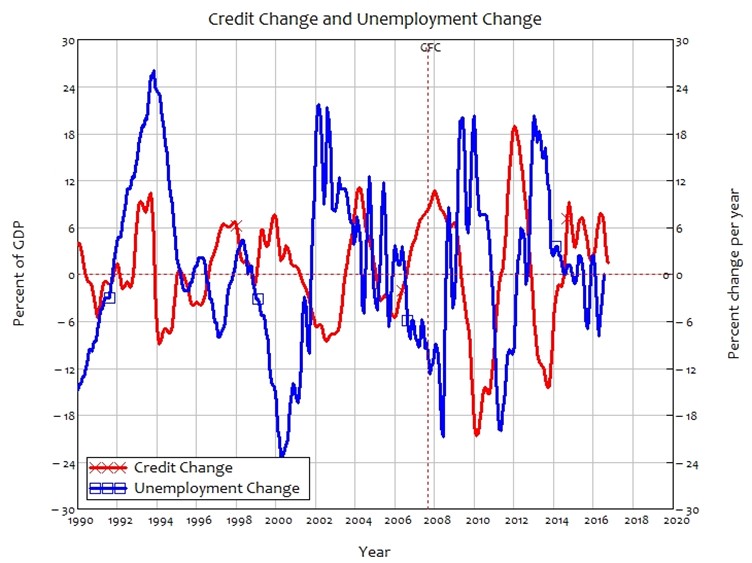

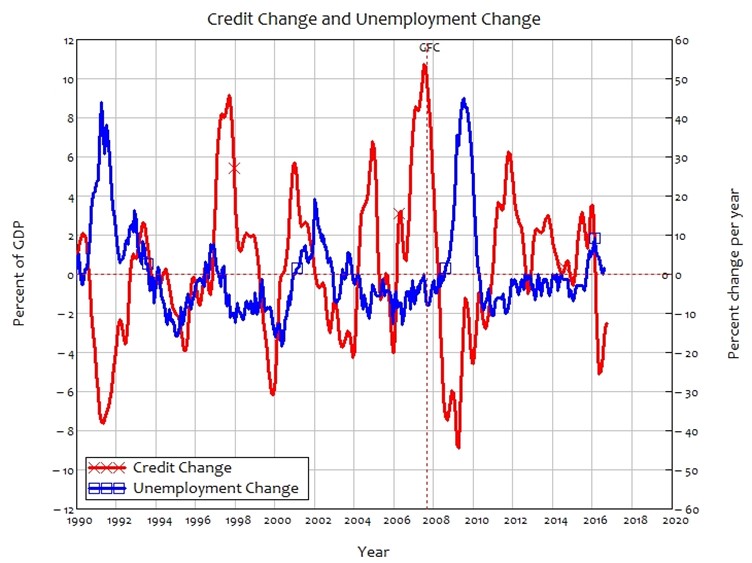

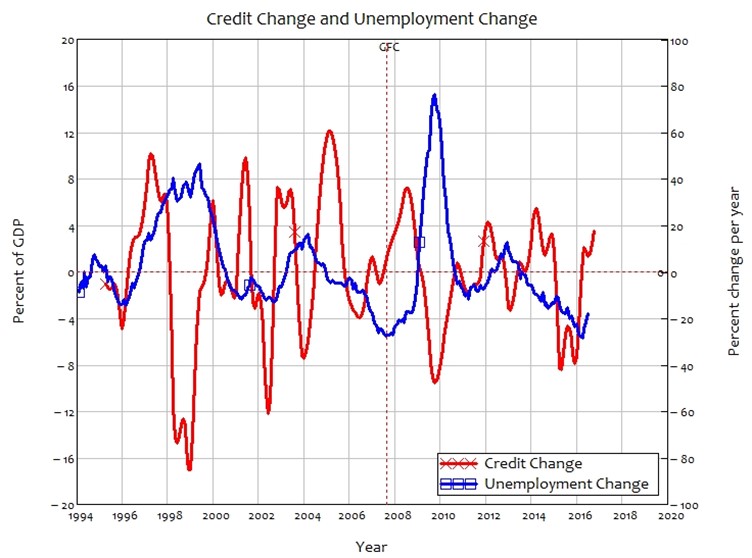

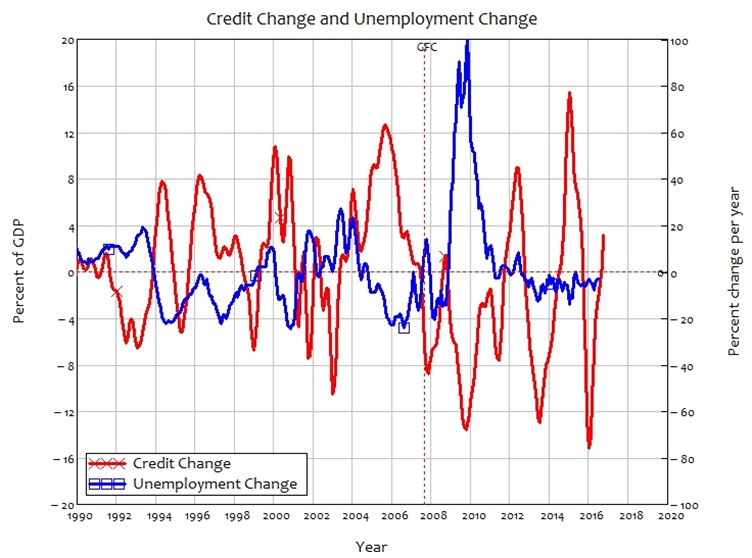

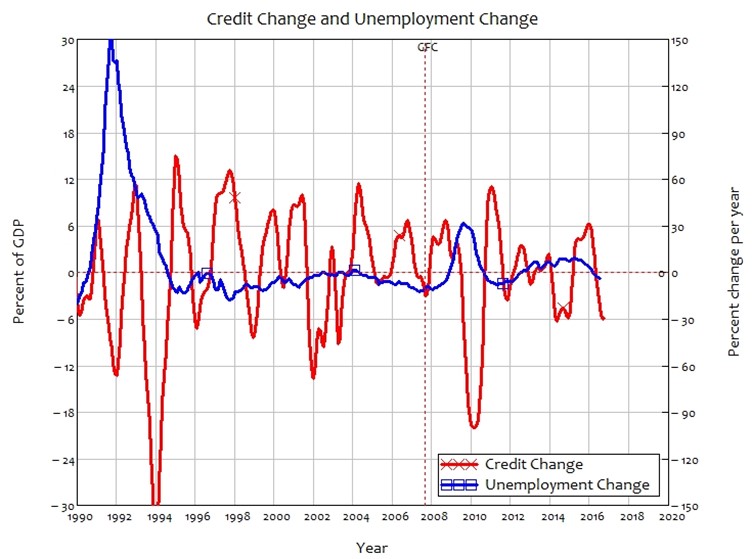

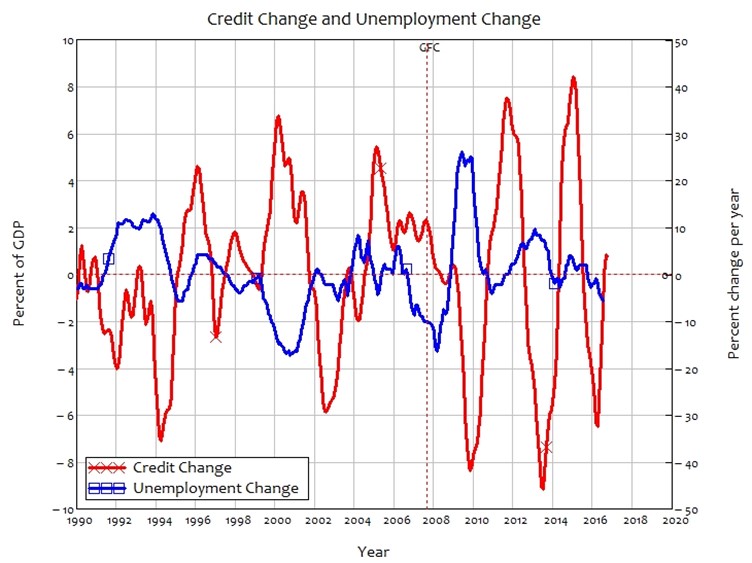

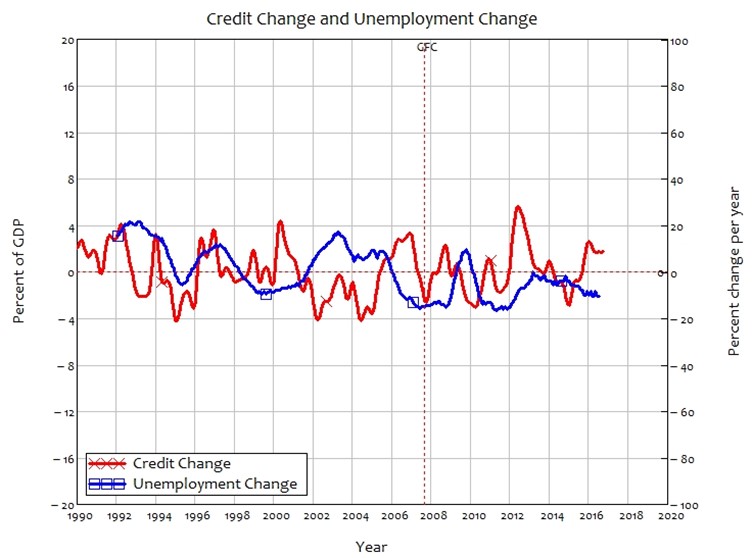

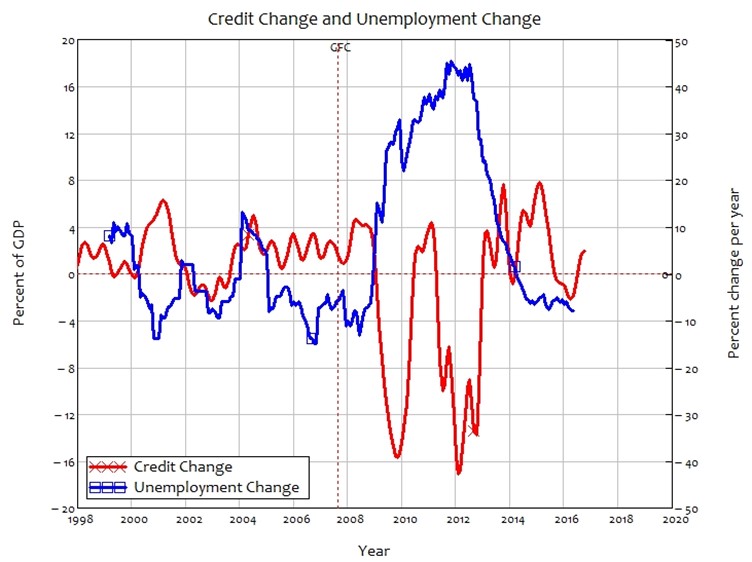

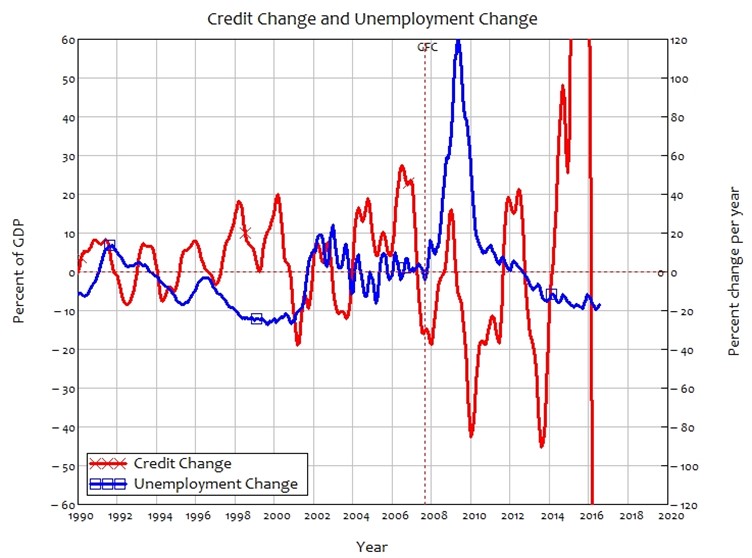

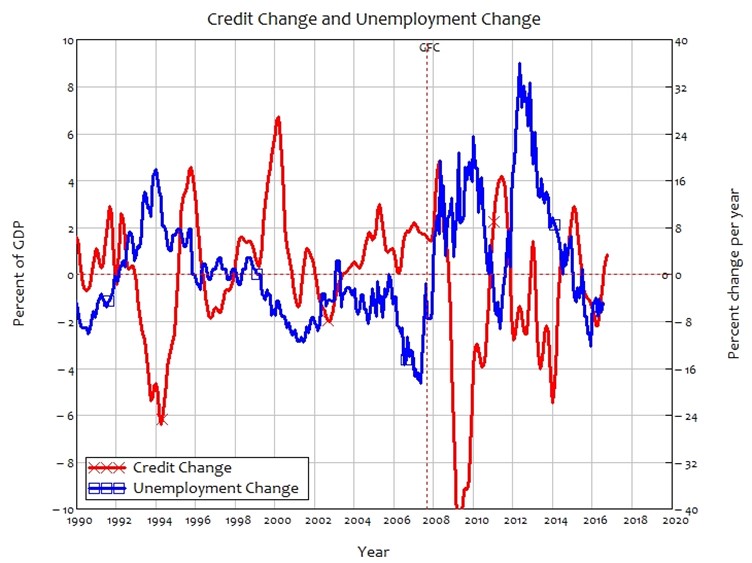

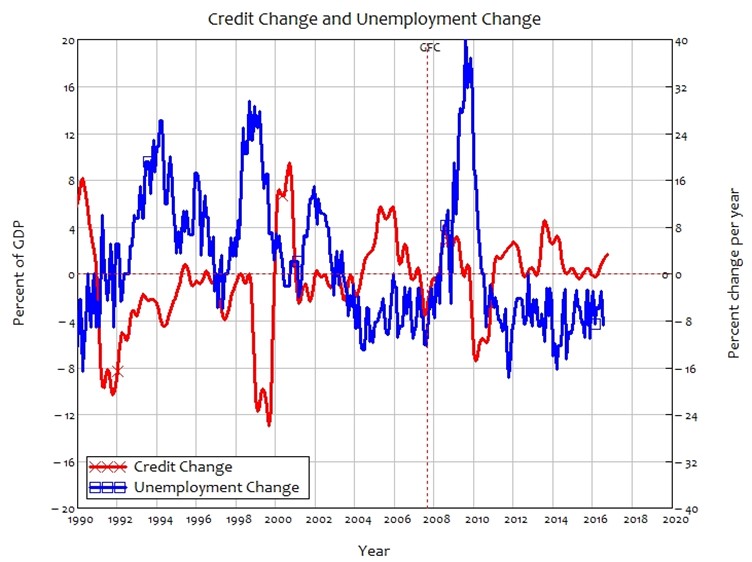

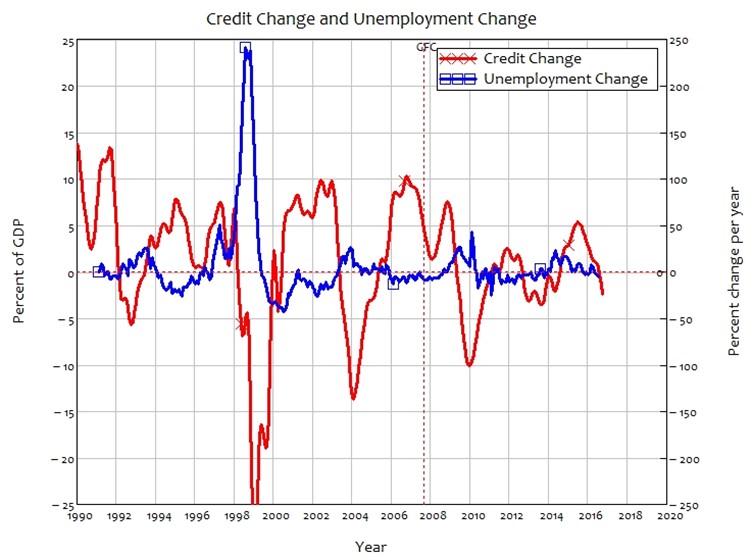

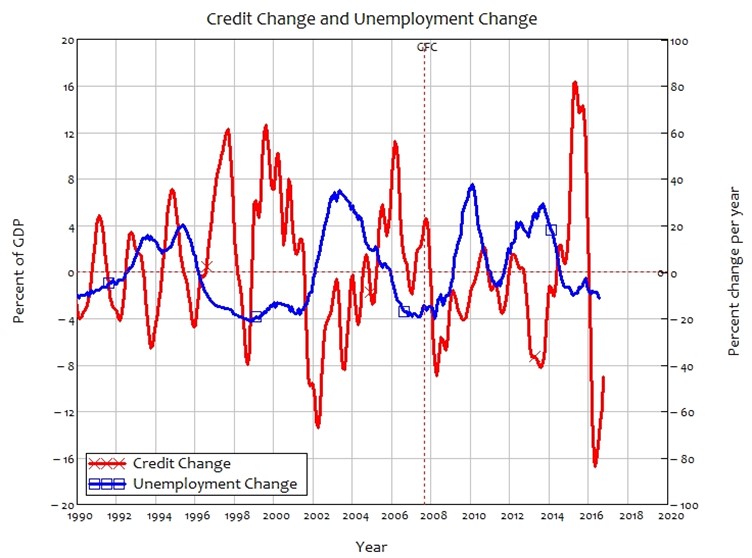

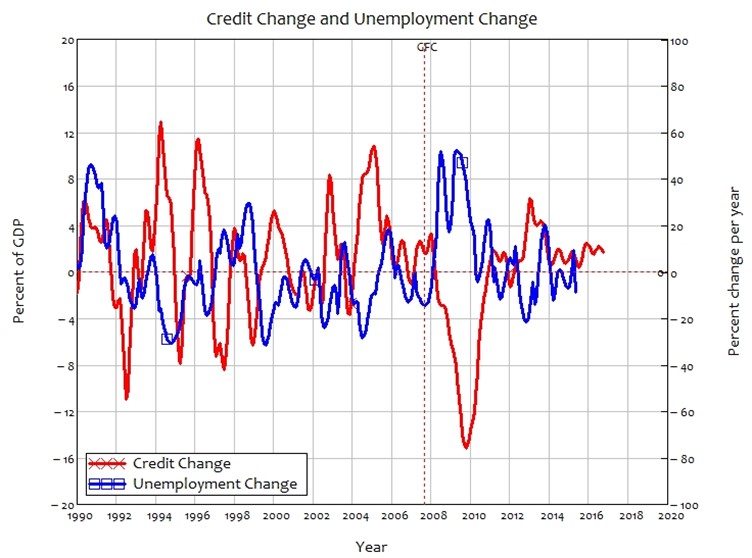

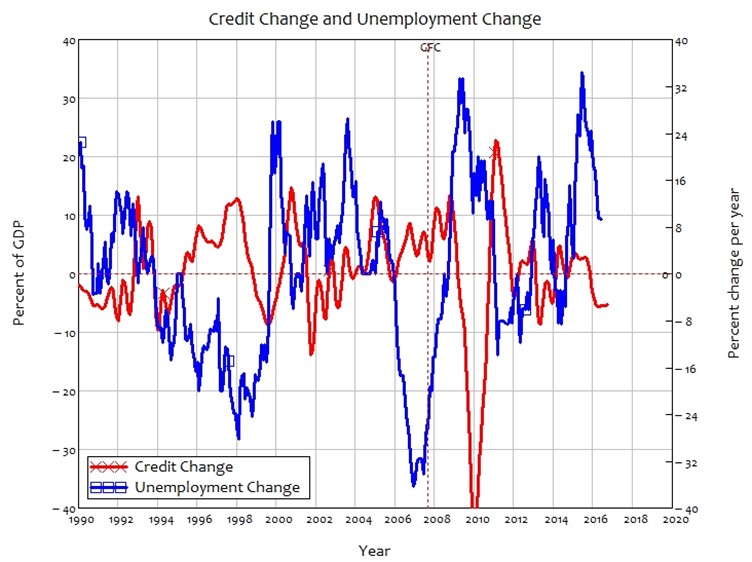

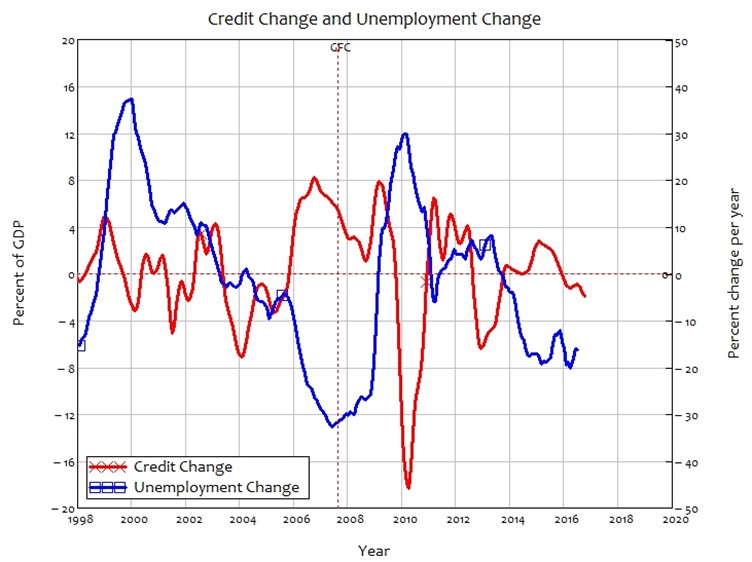

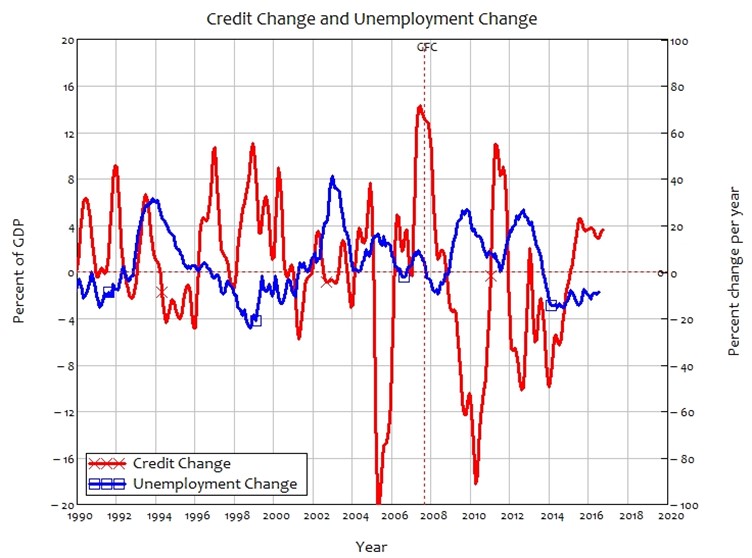

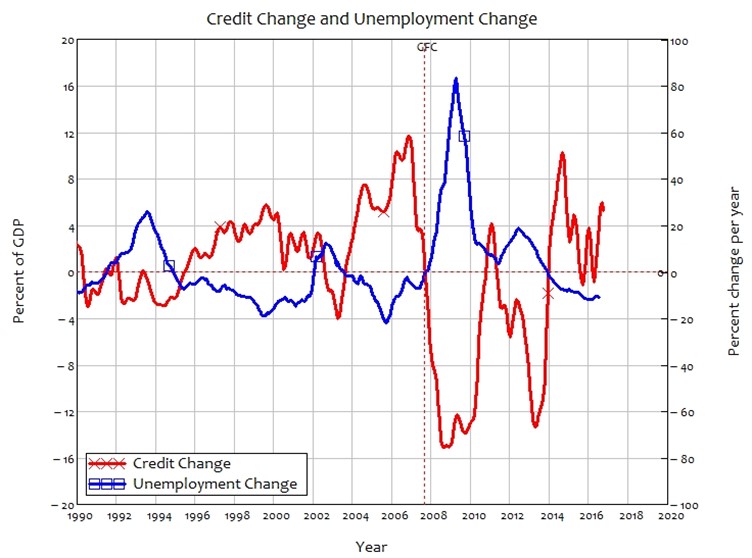

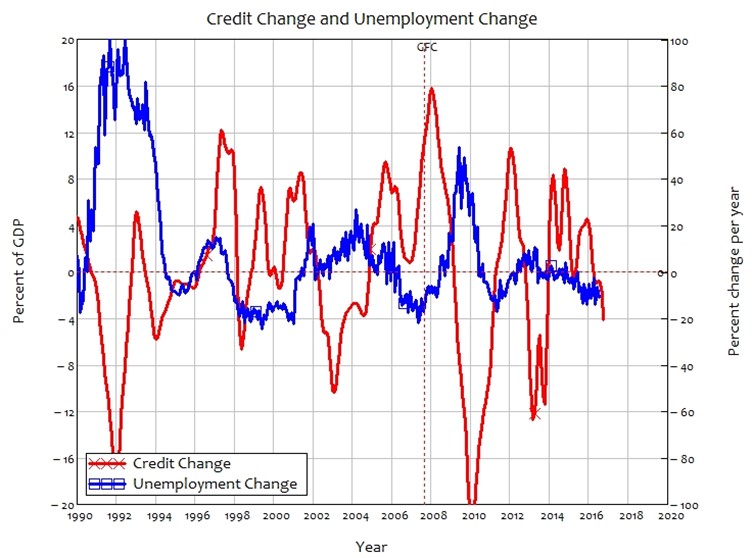

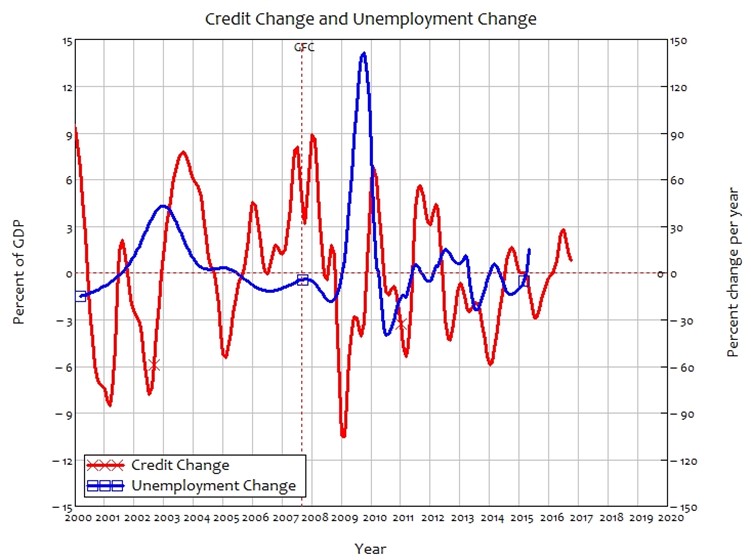

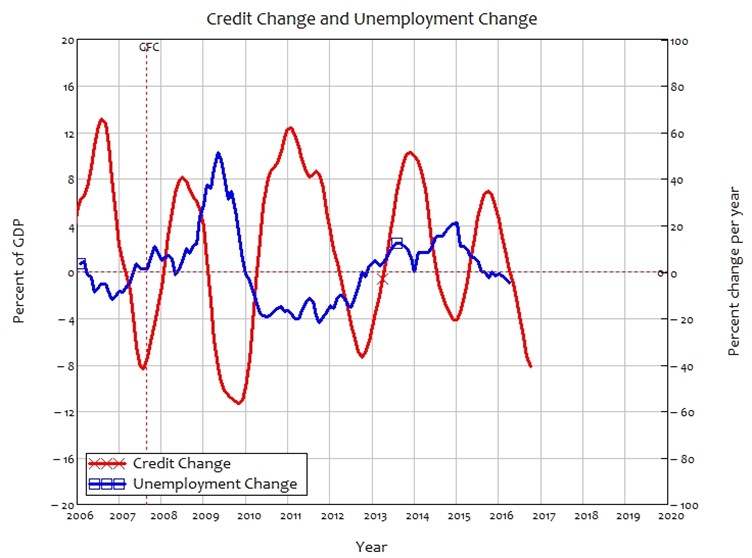

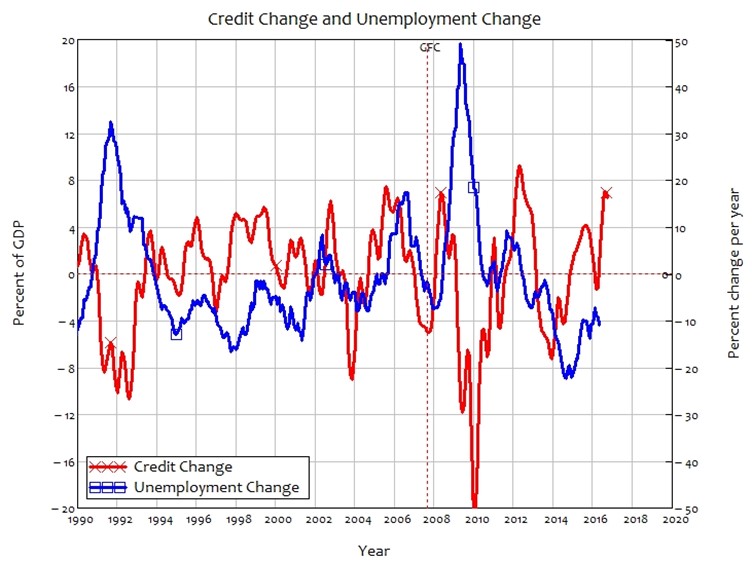

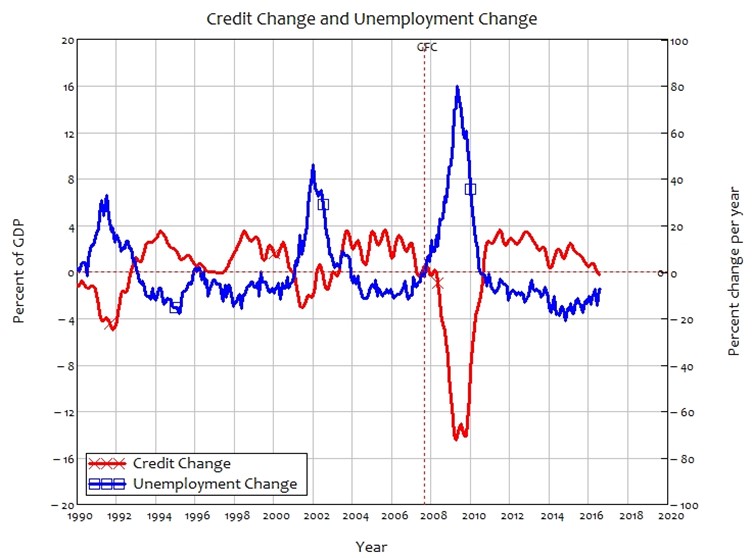

Change in Credit and Change in Unemployment 122

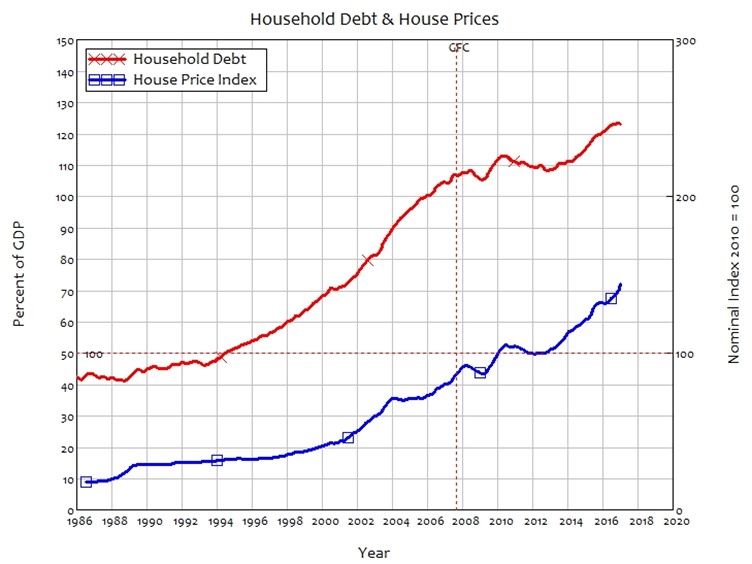

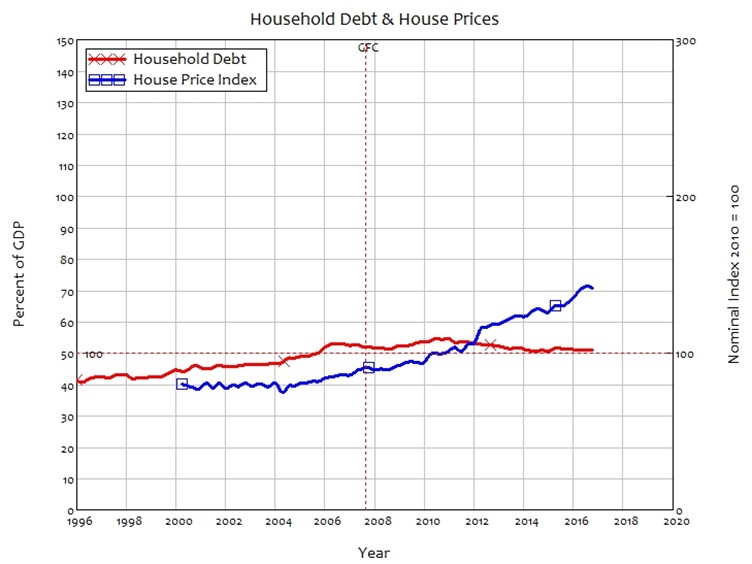

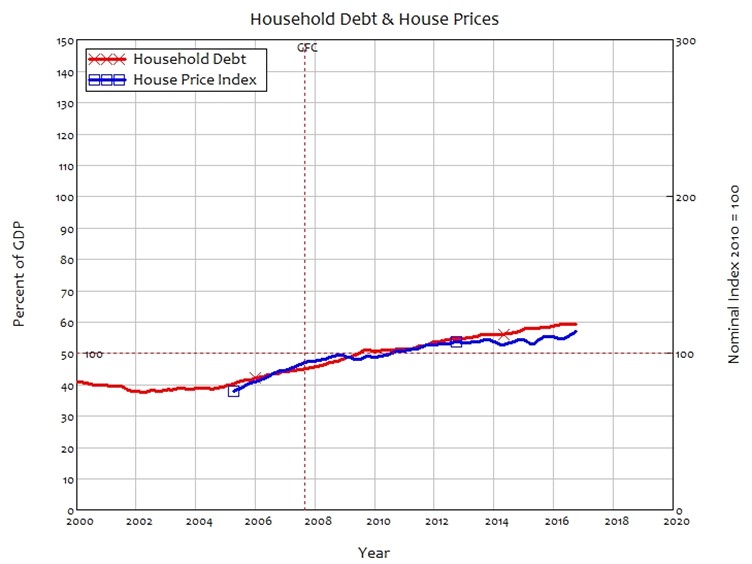

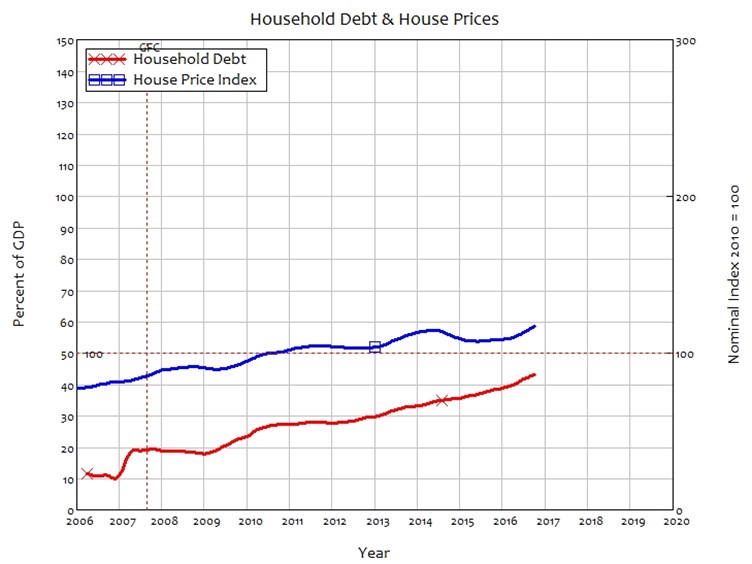

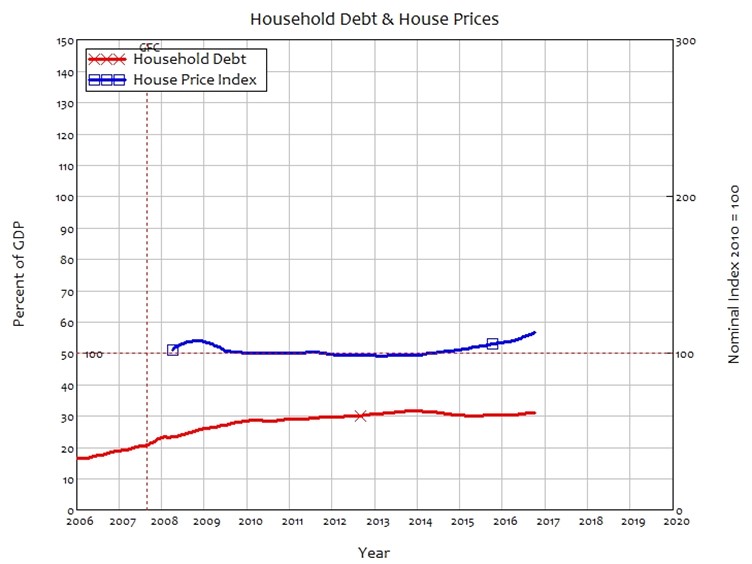

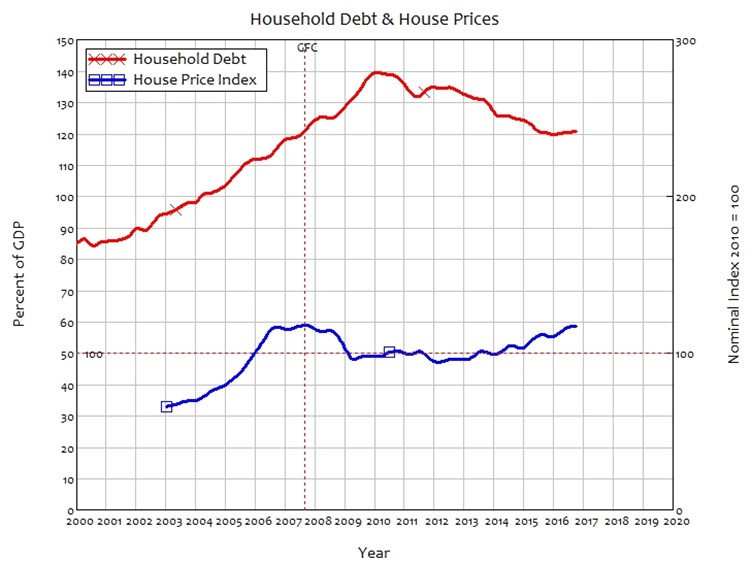

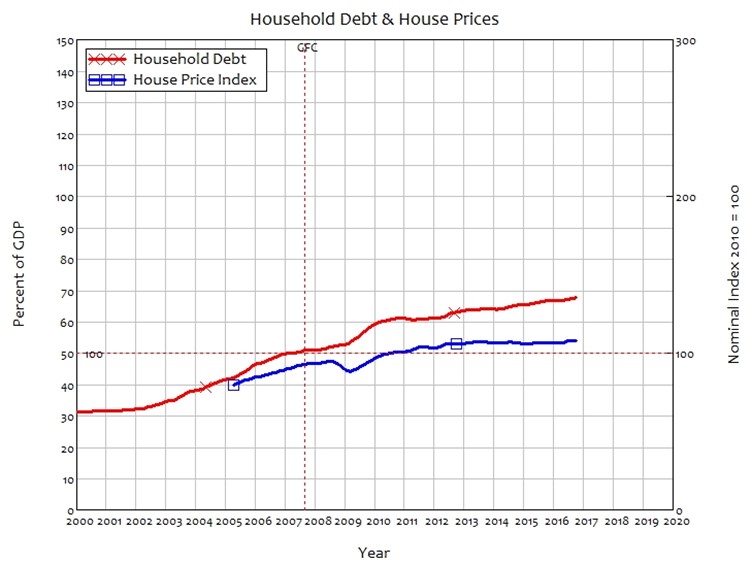

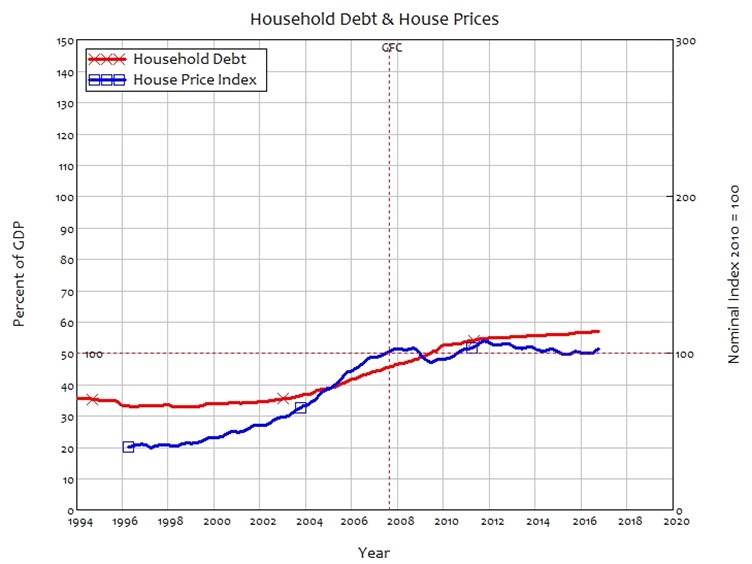

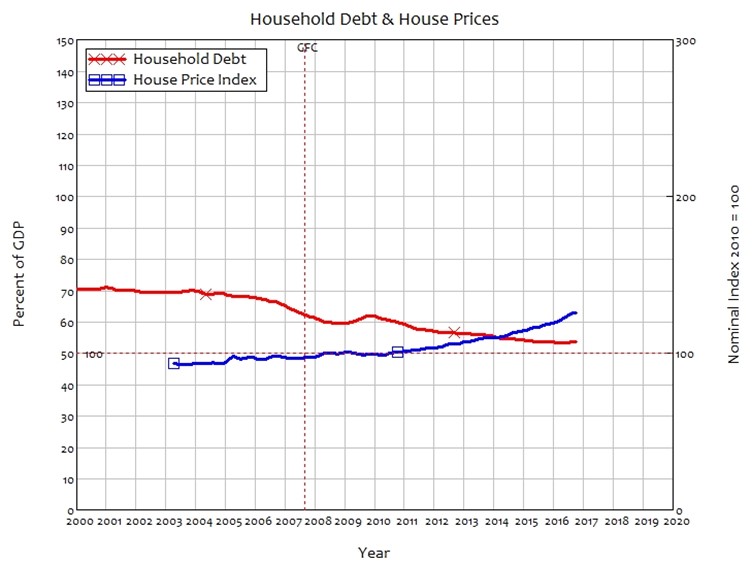

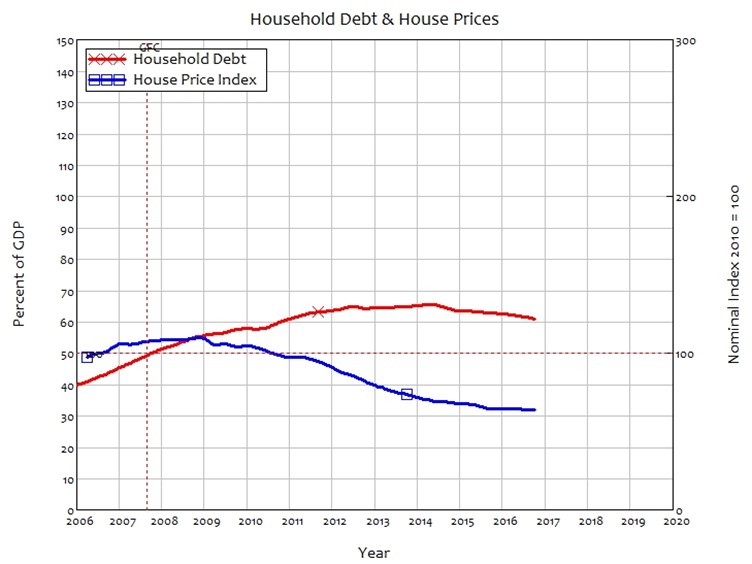

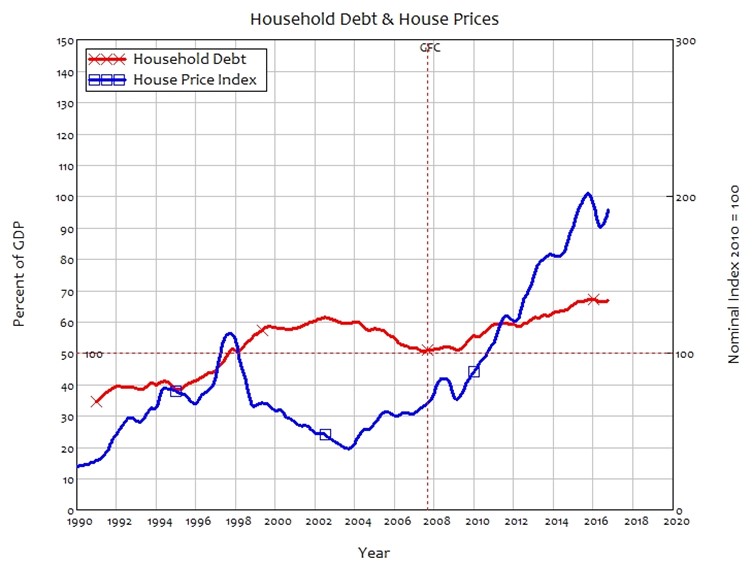

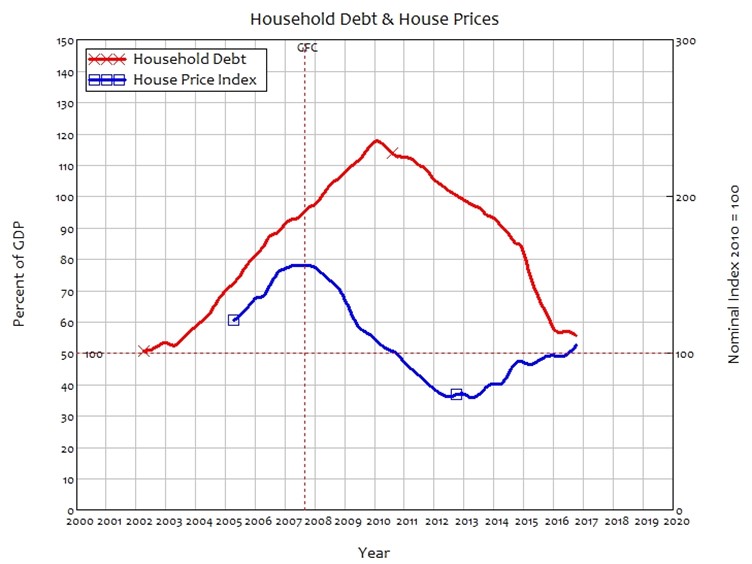

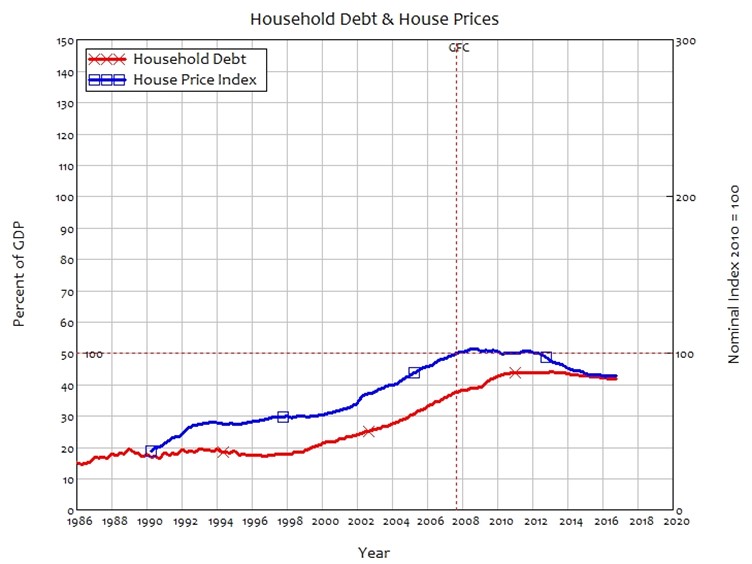

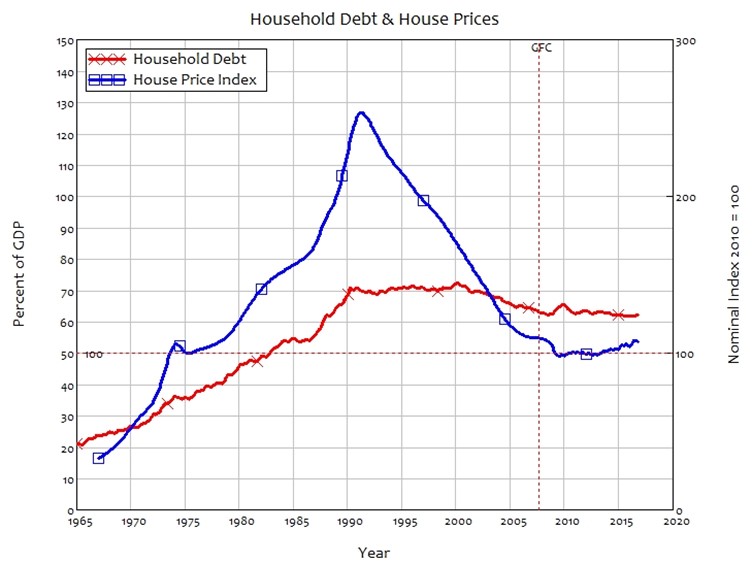

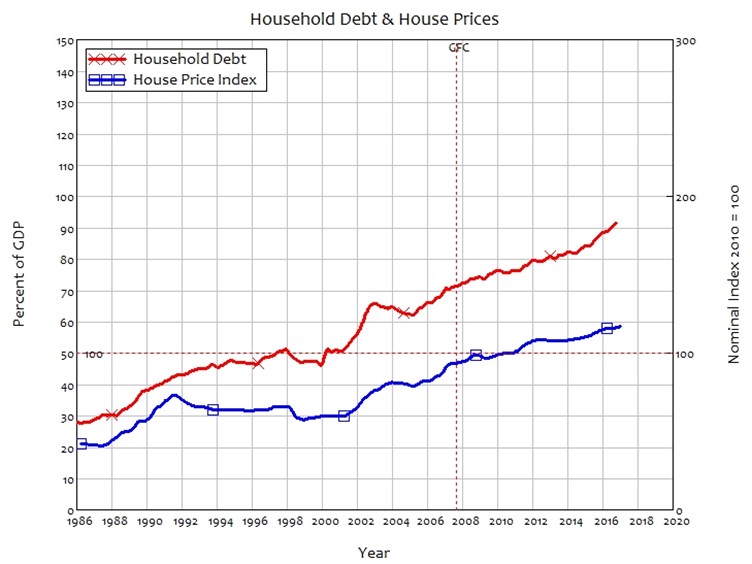

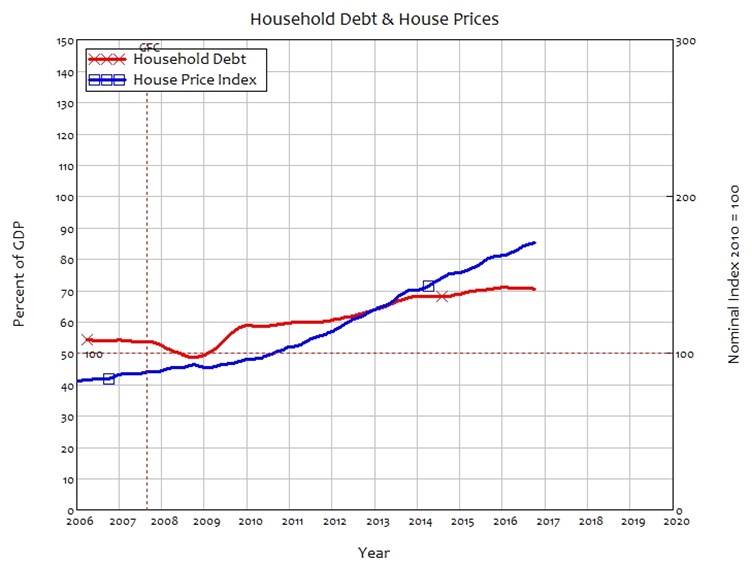

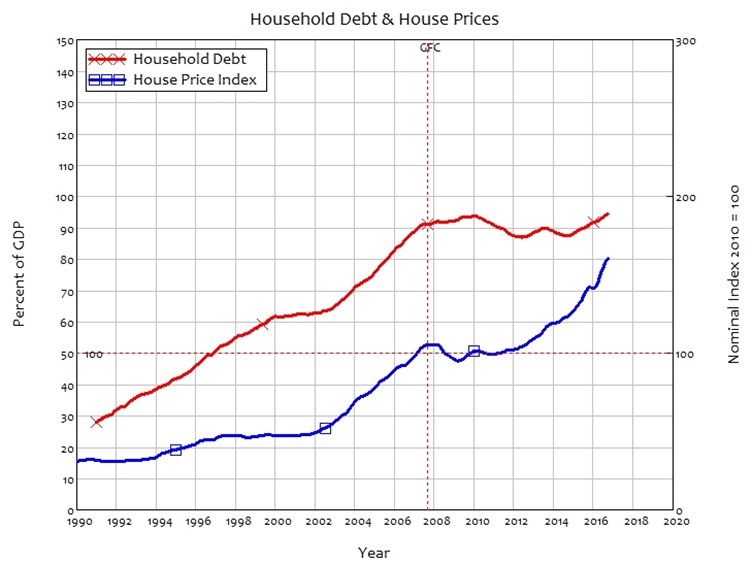

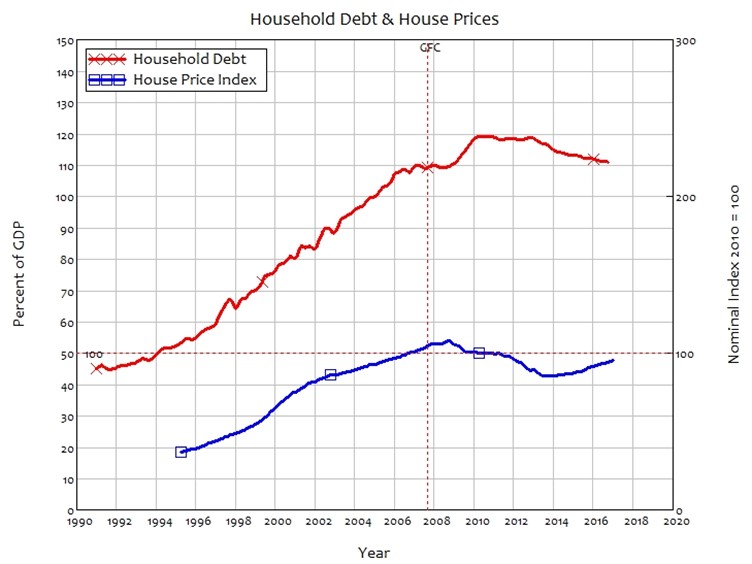

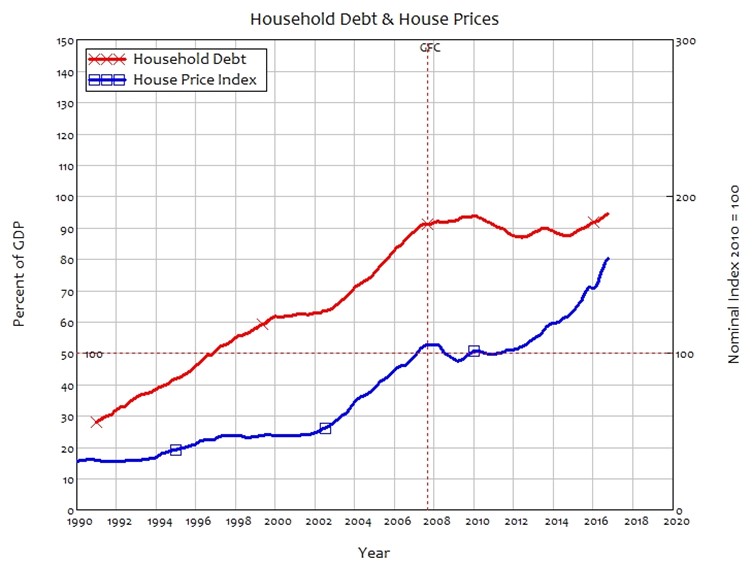

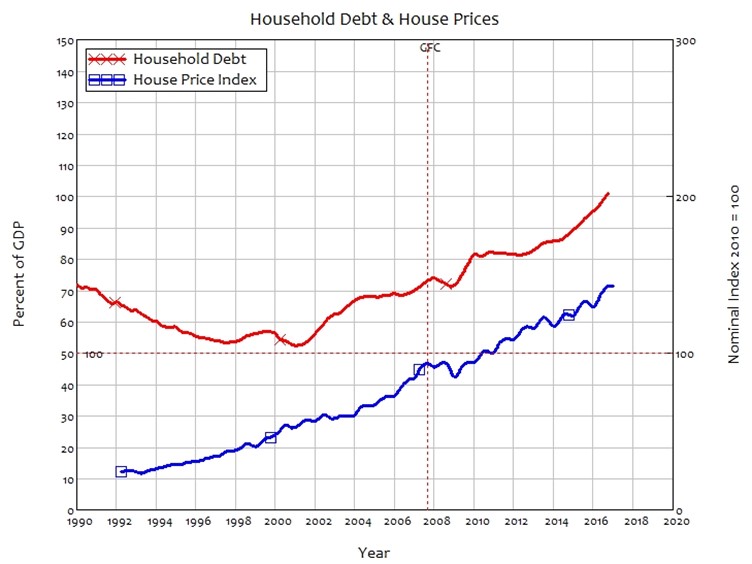

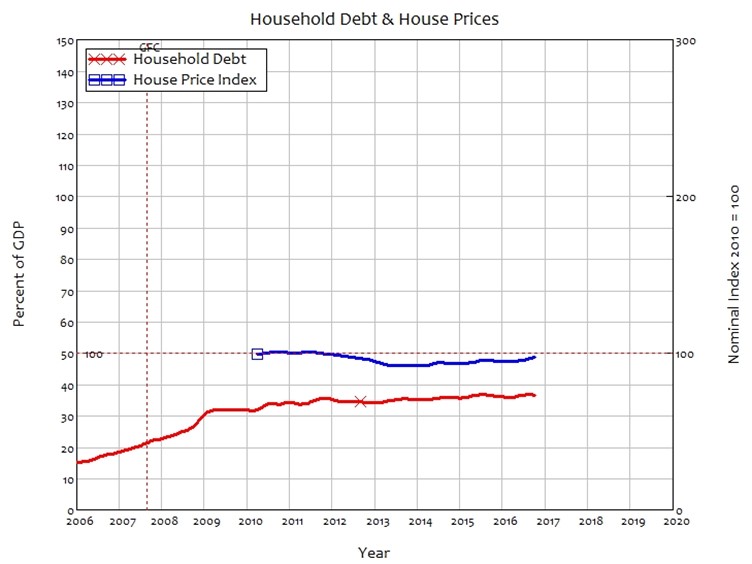

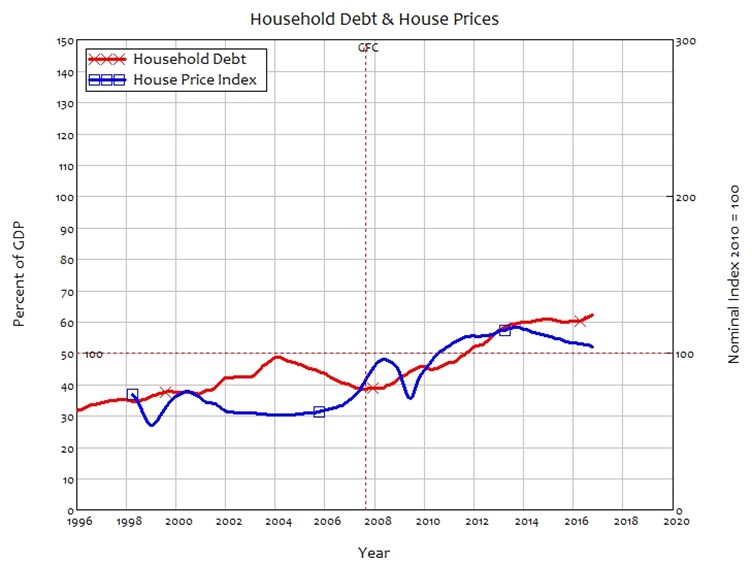

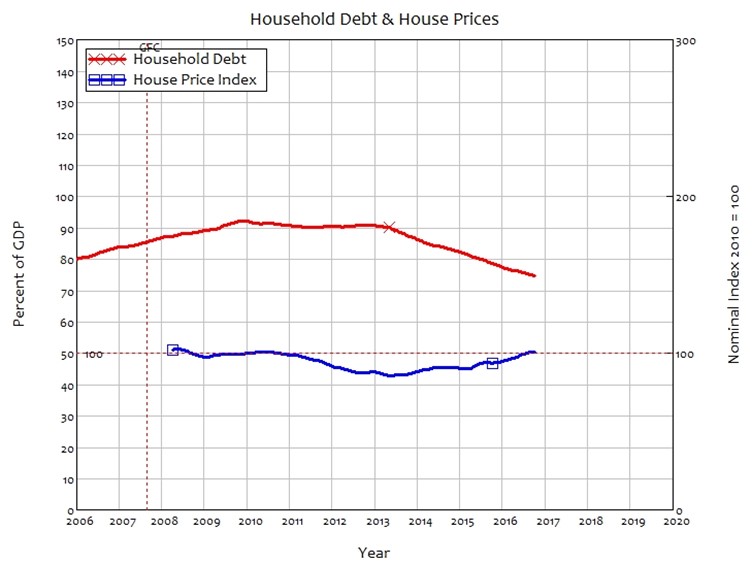

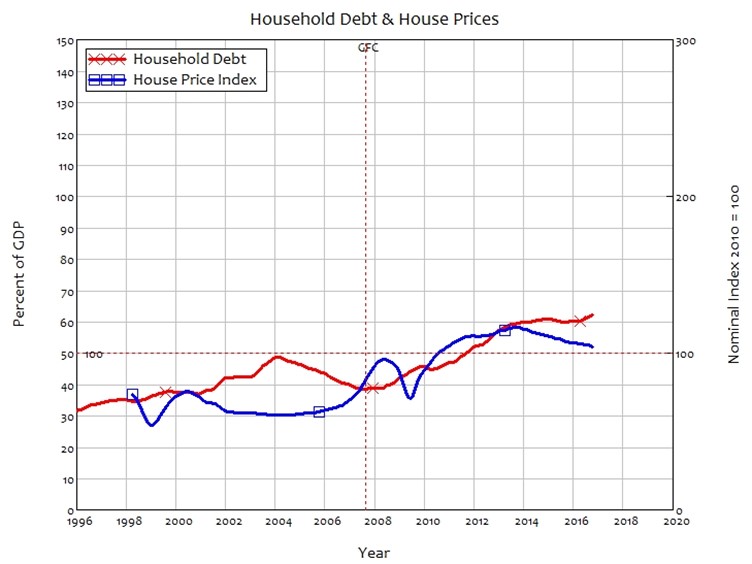

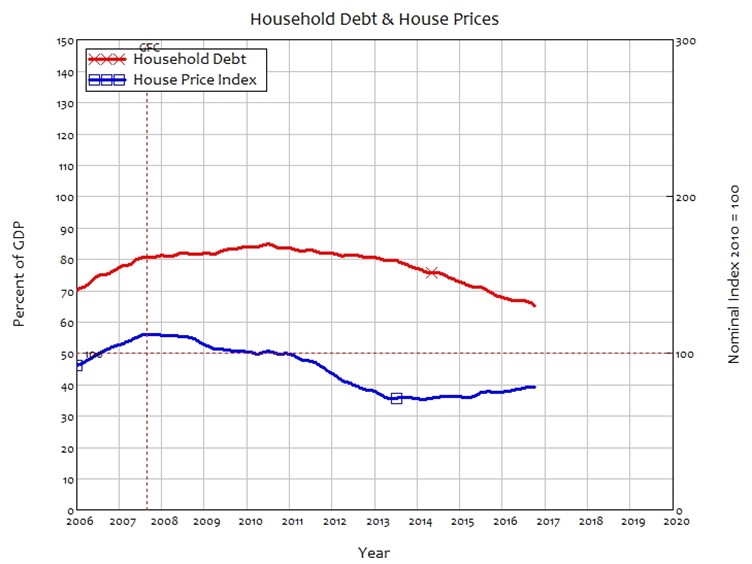

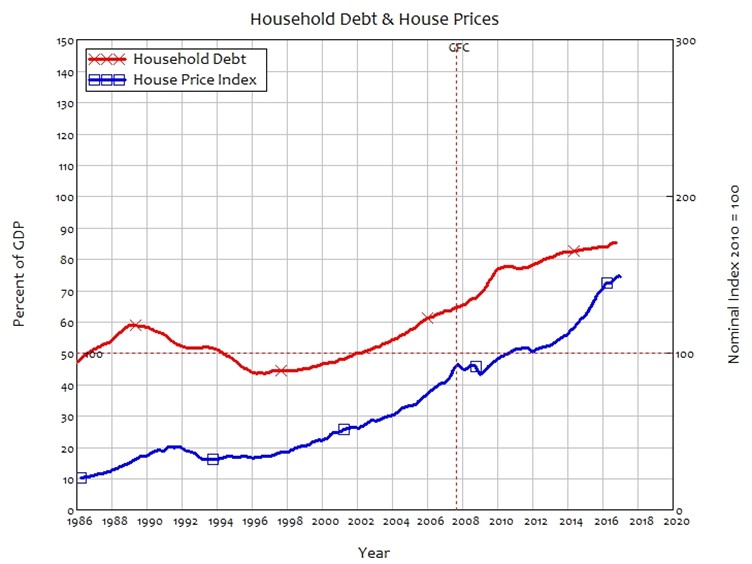

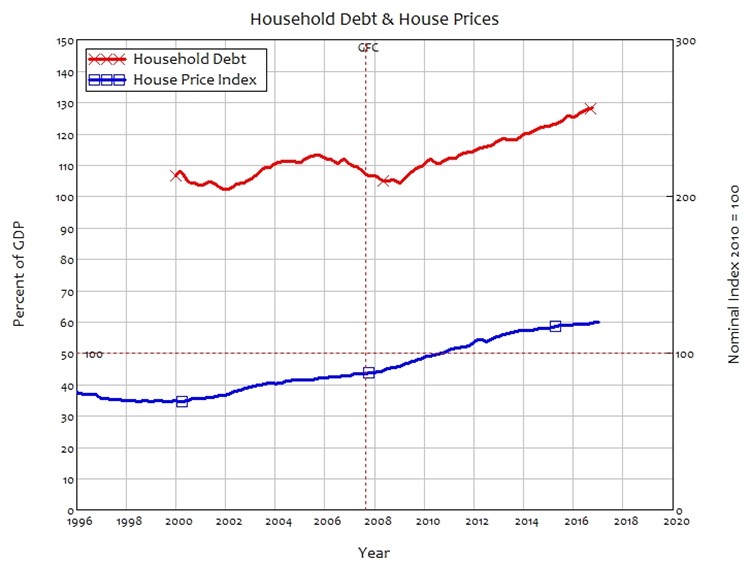

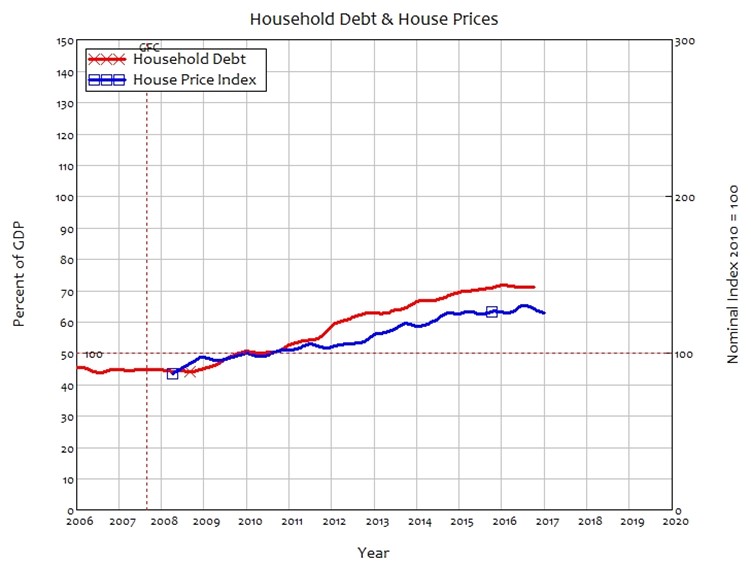

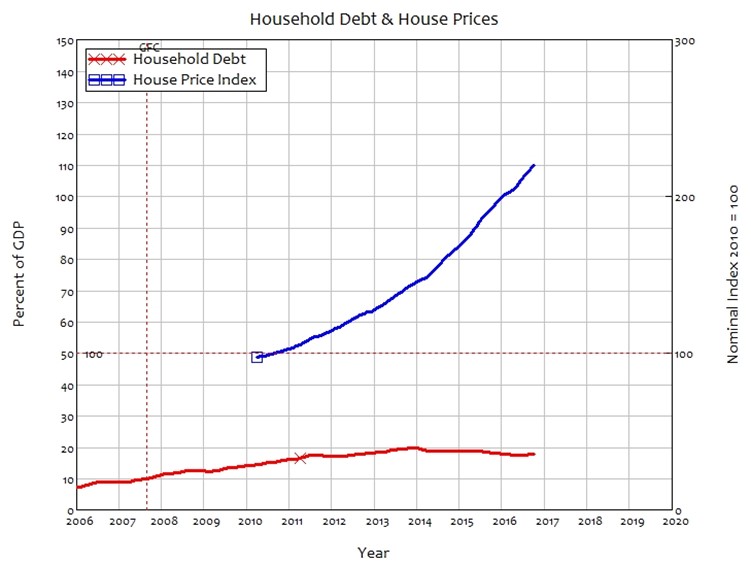

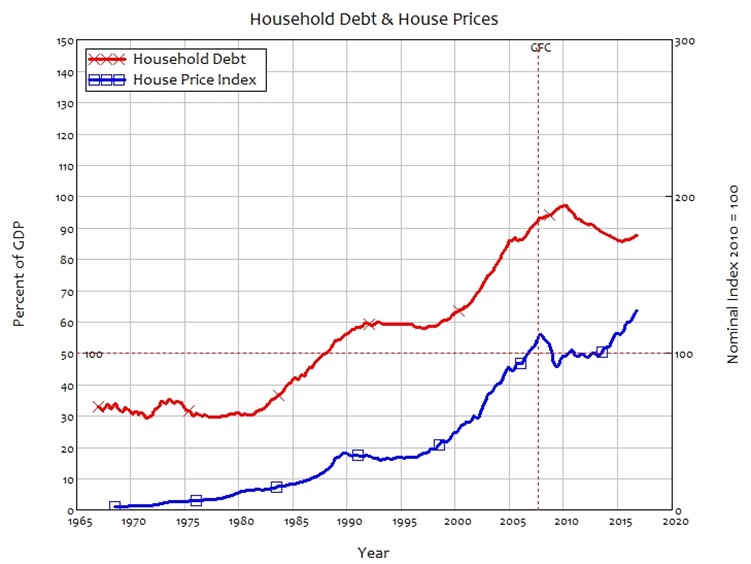

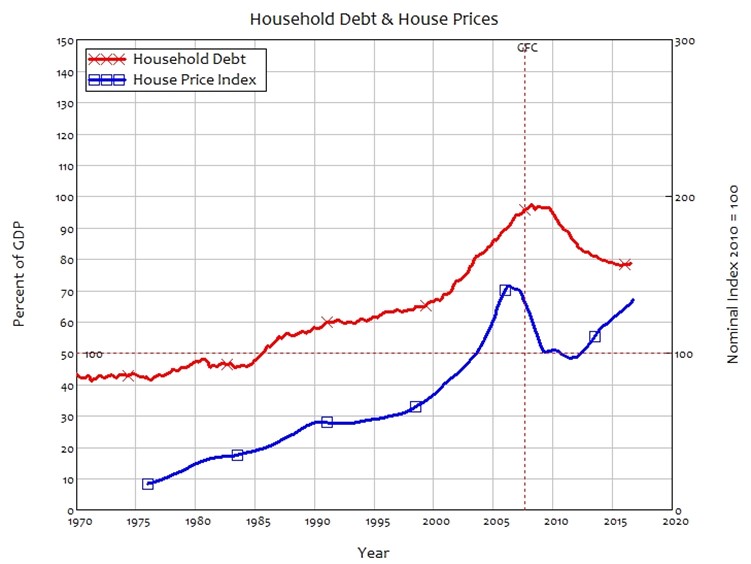

Household Debt and House Prices 147

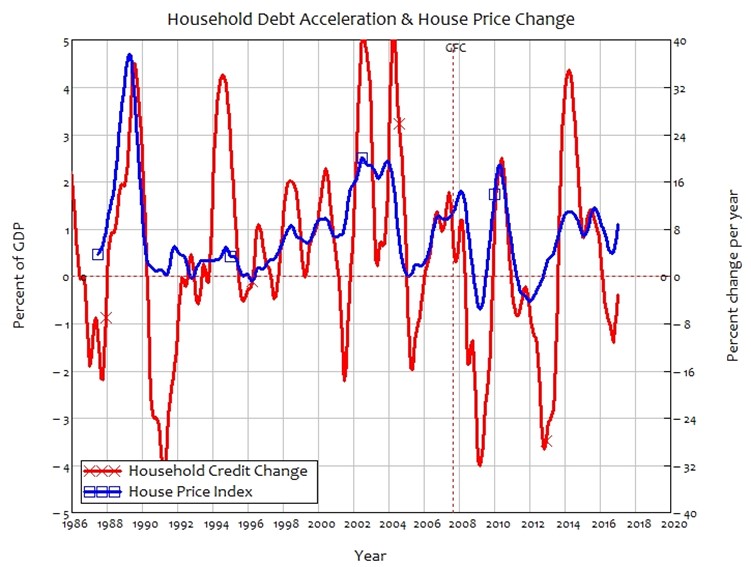

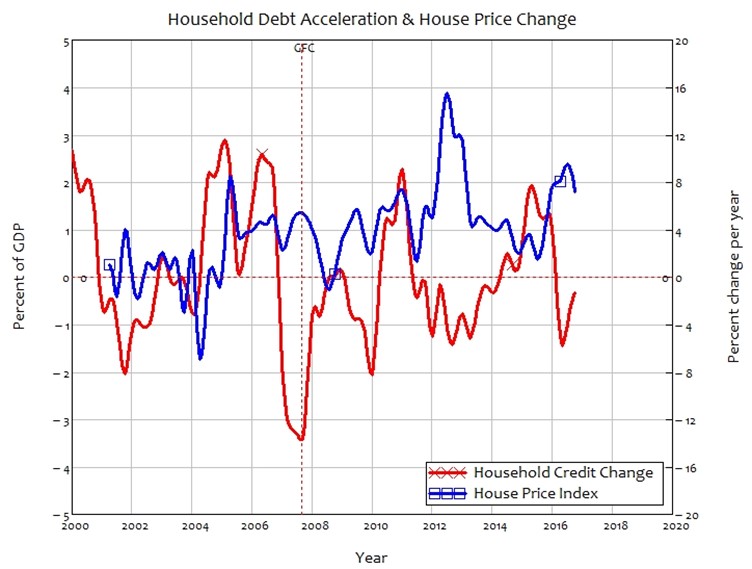

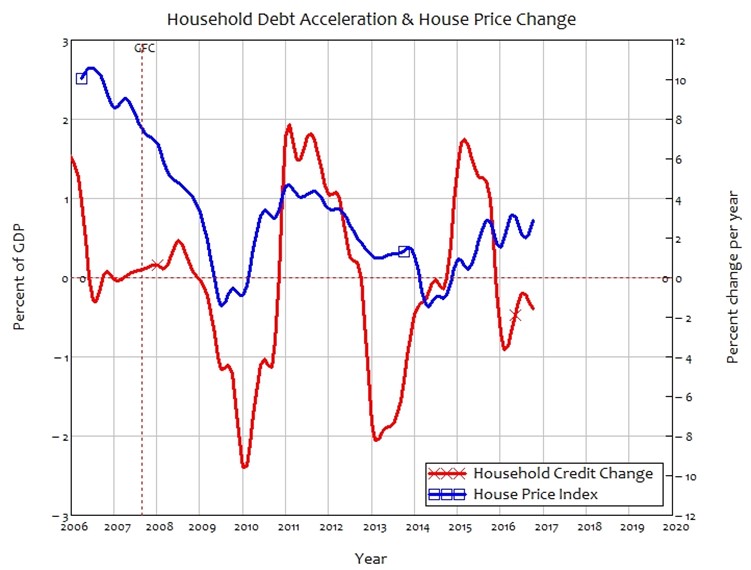

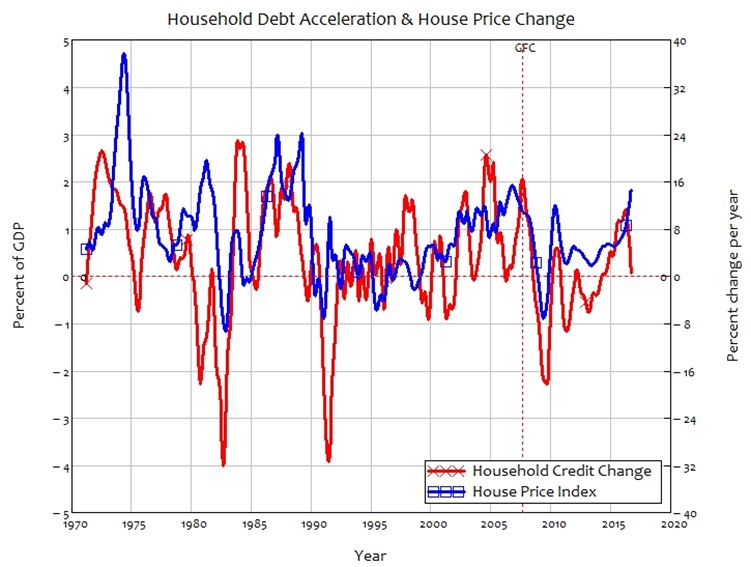

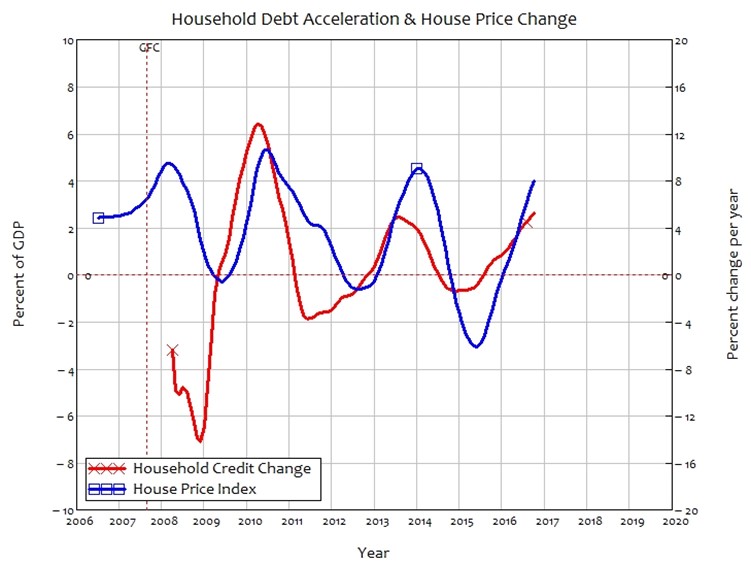

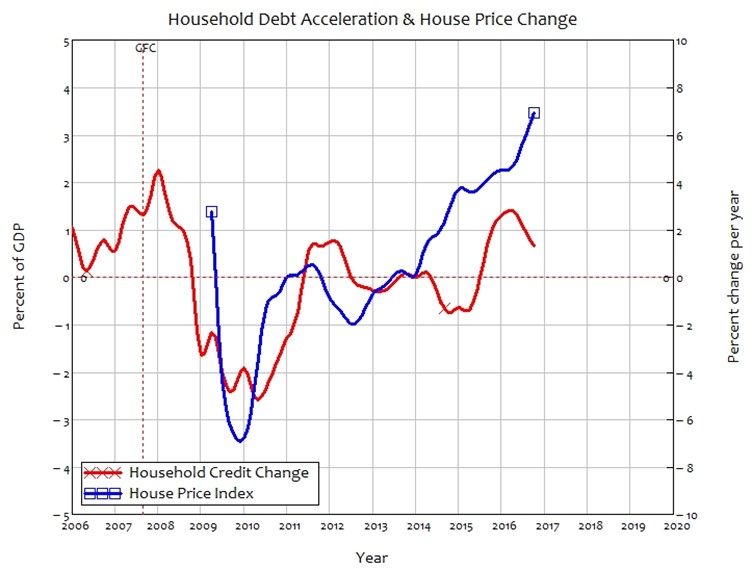

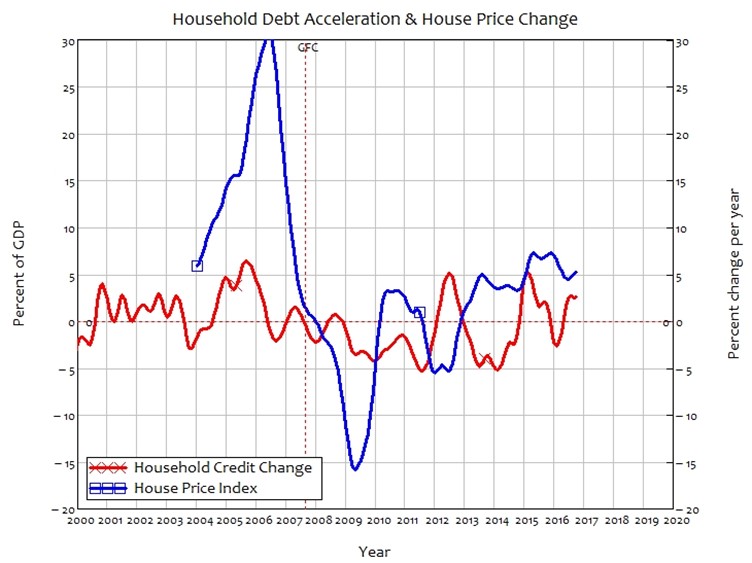

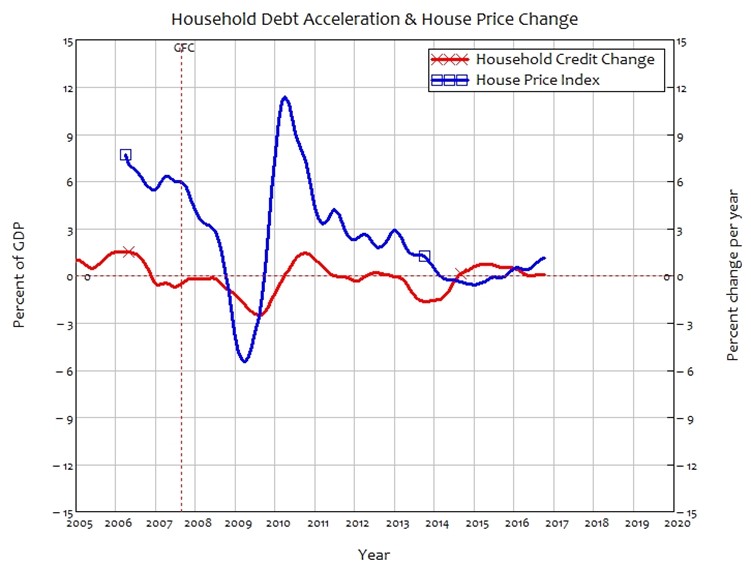

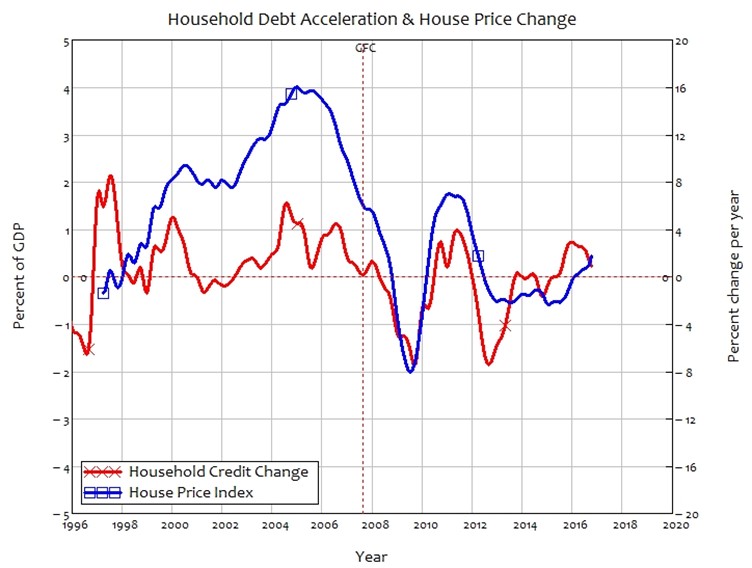

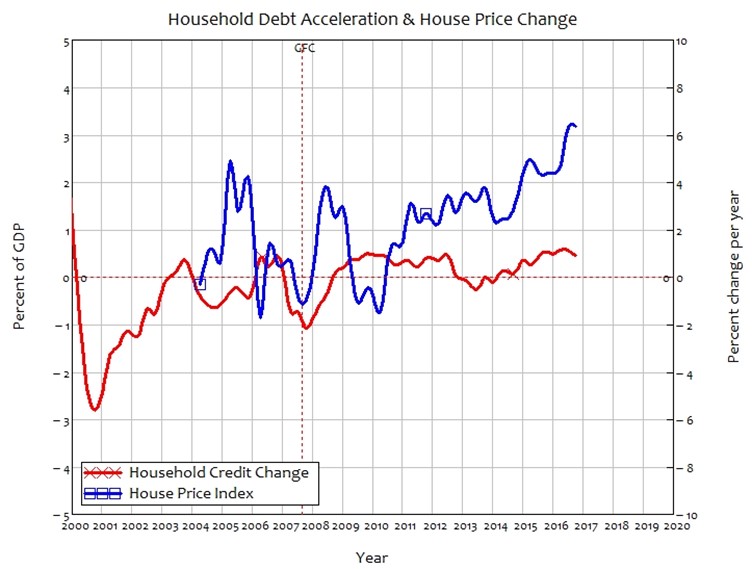

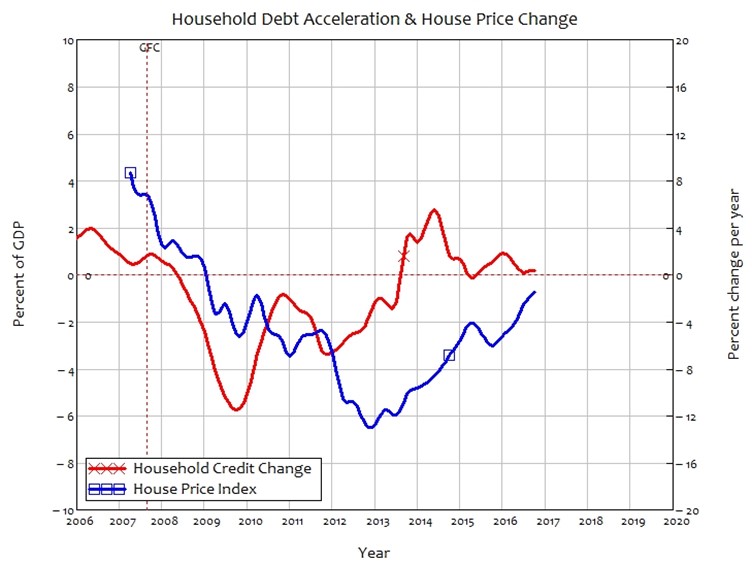

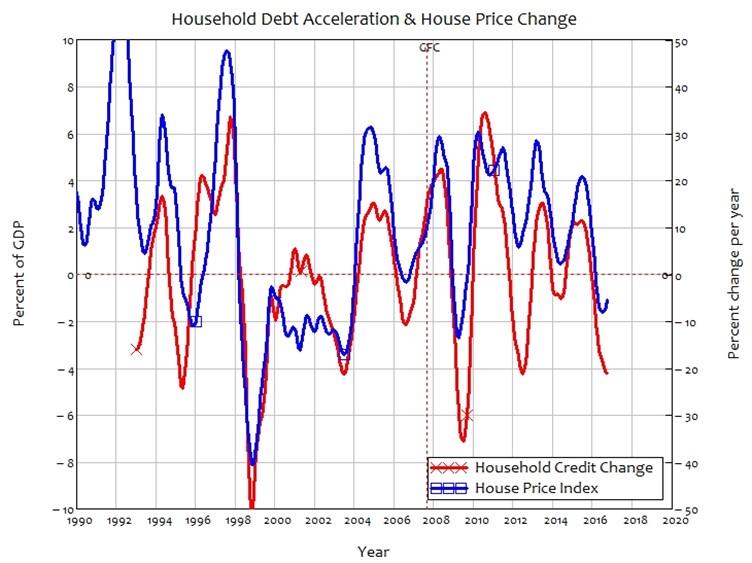

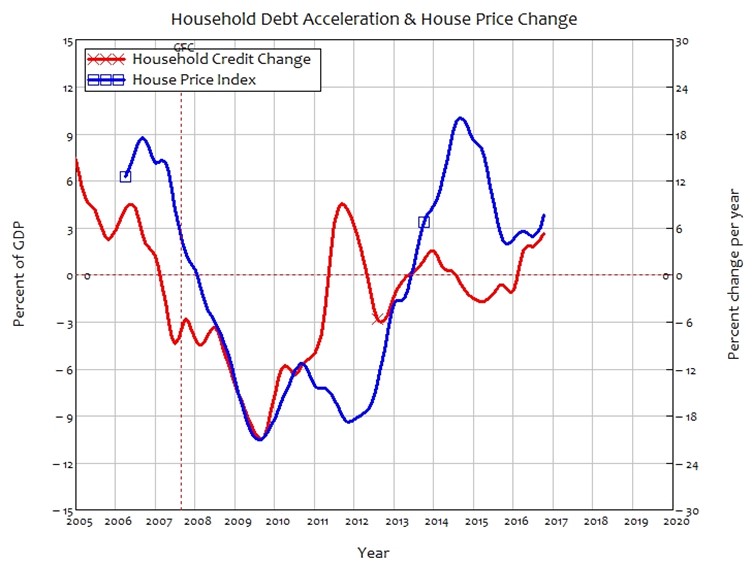

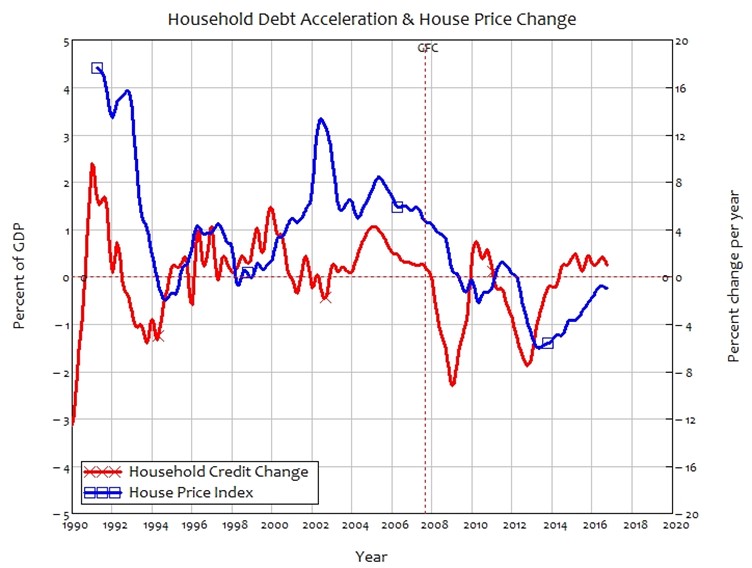

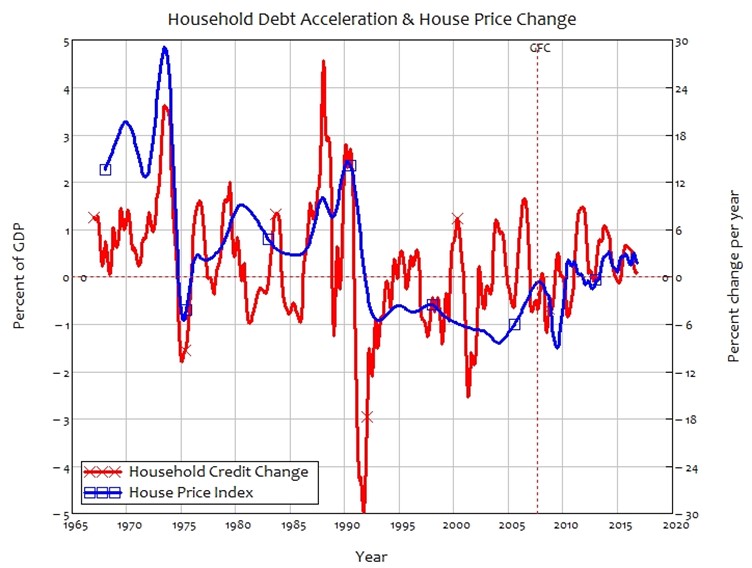

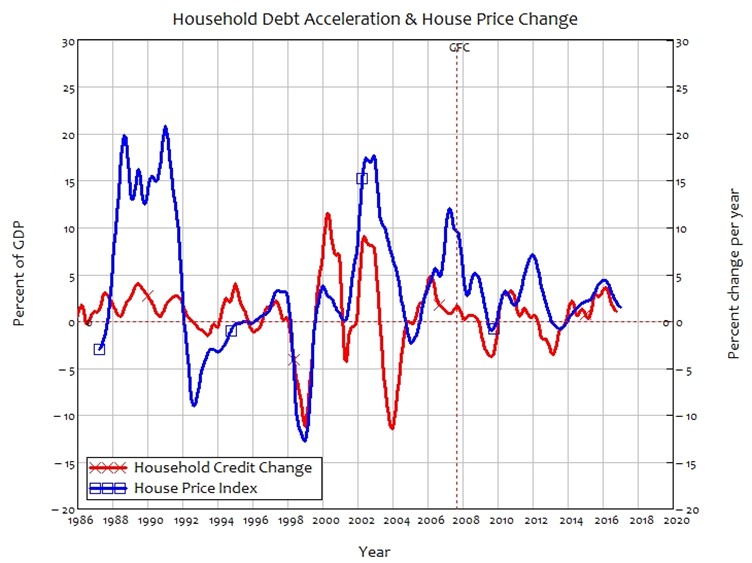

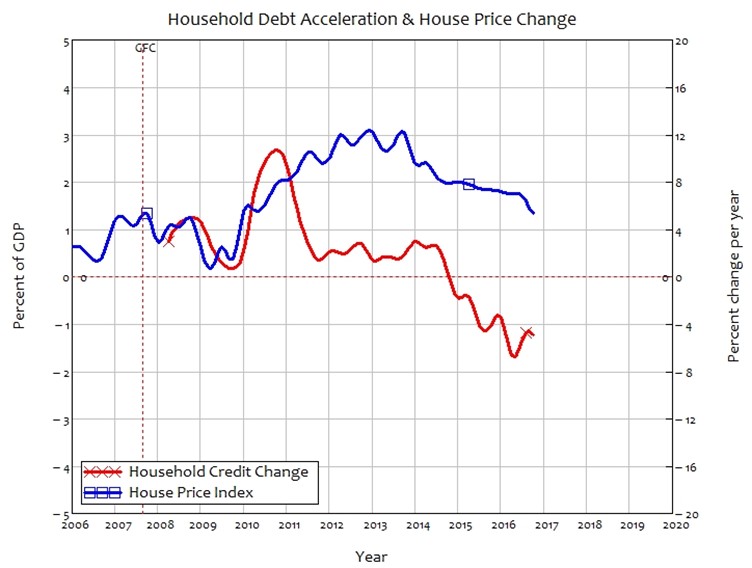

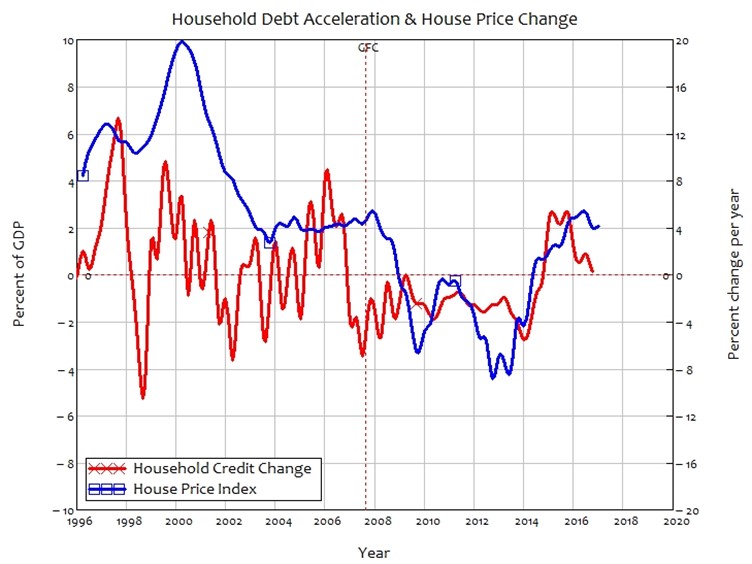

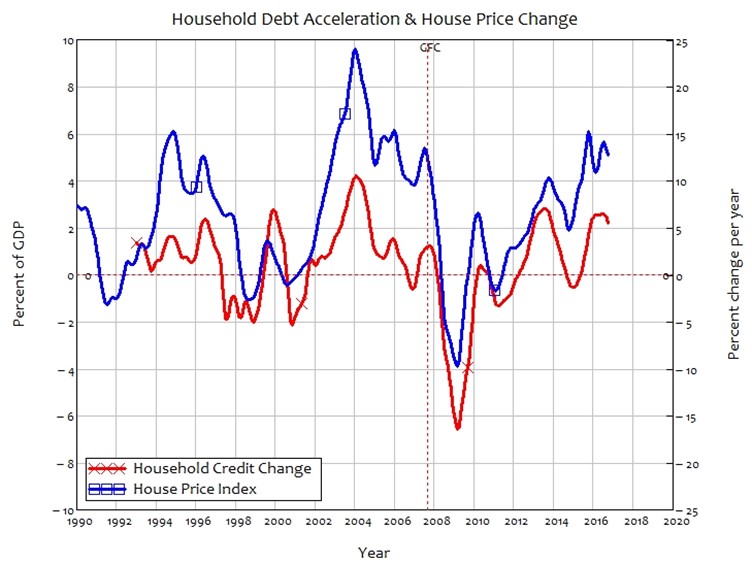

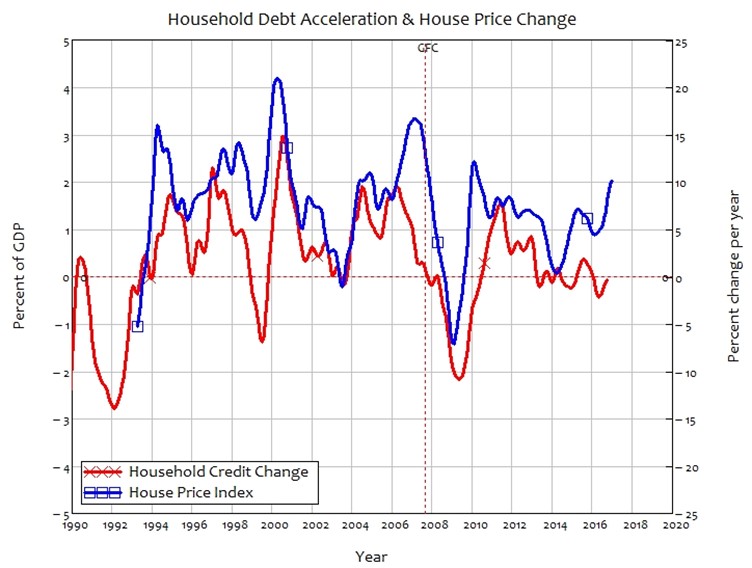

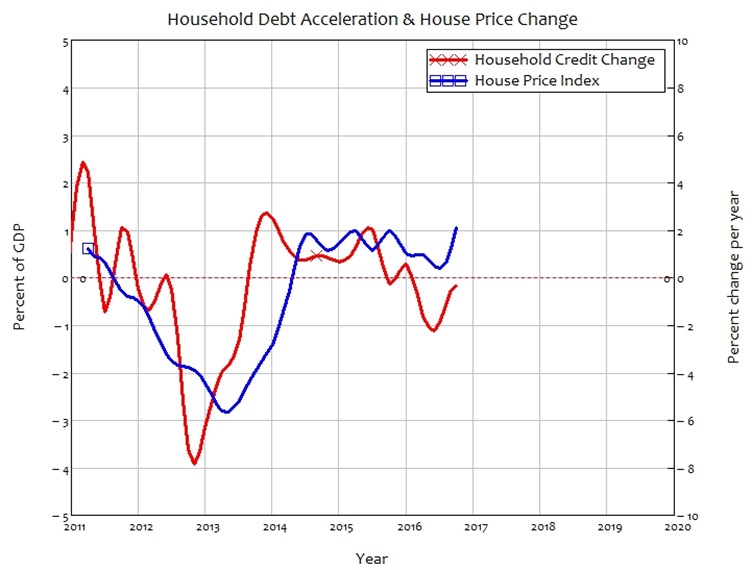

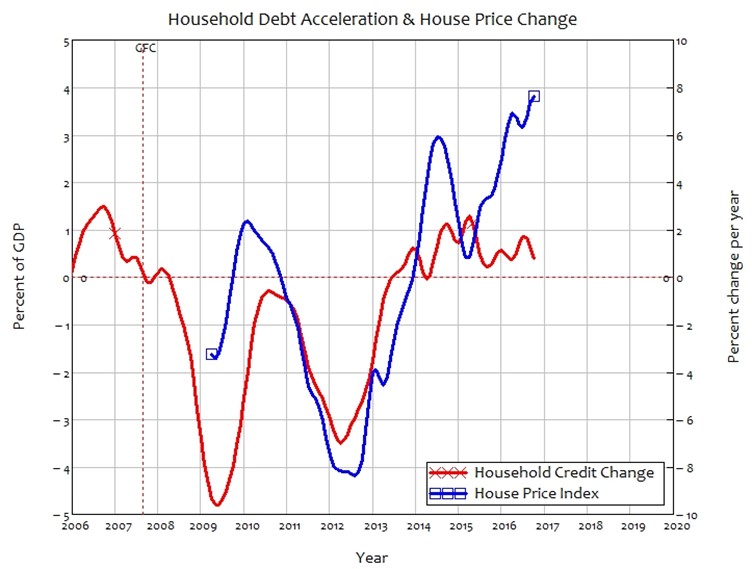

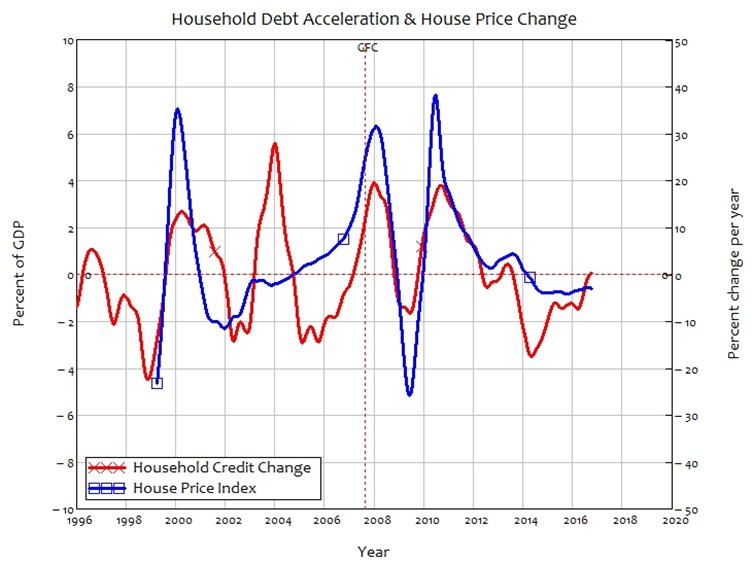

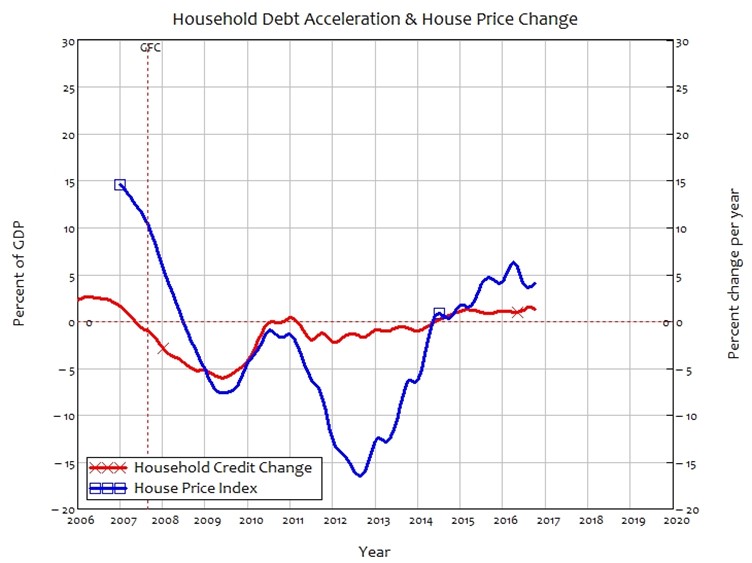

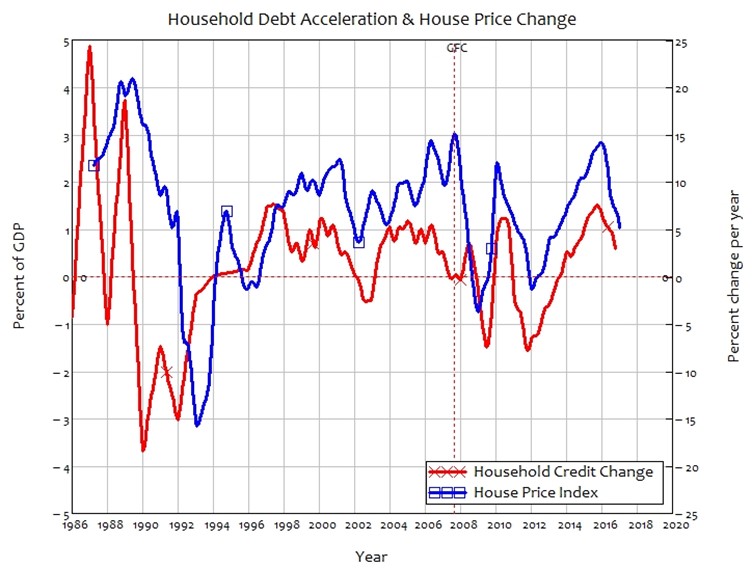

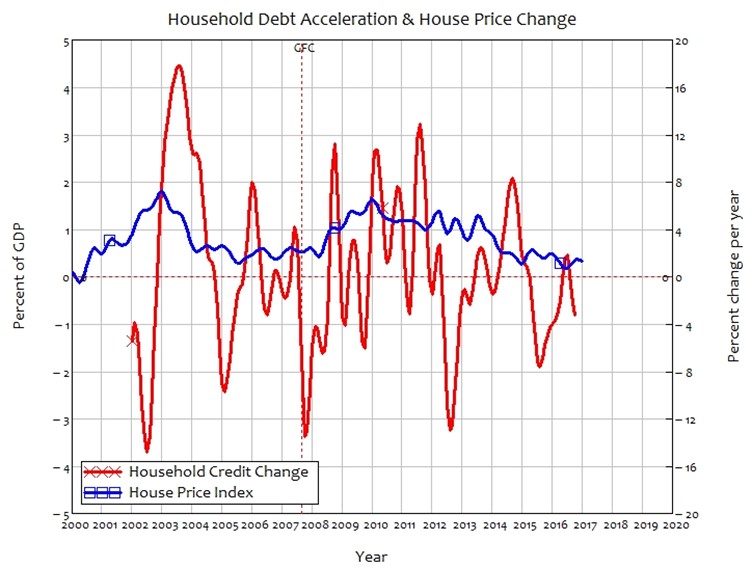

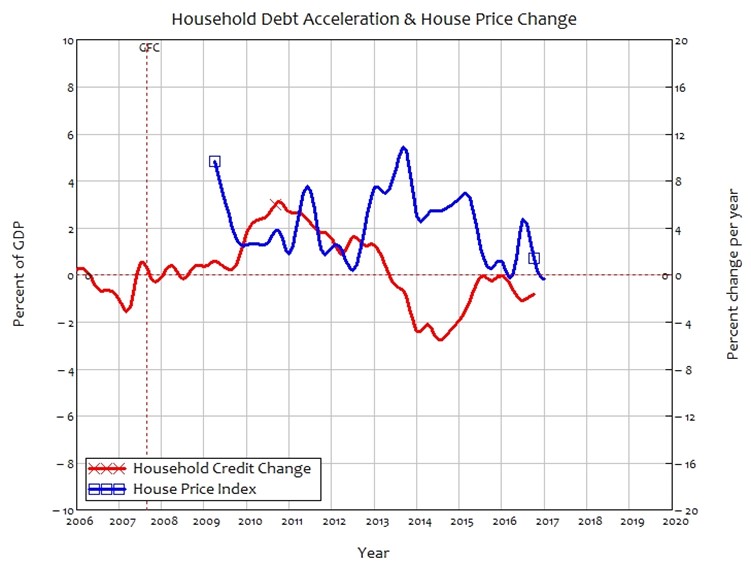

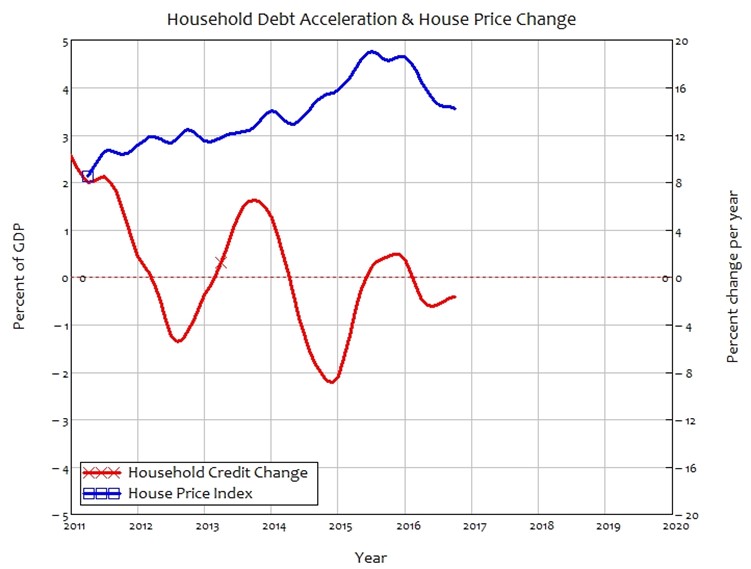

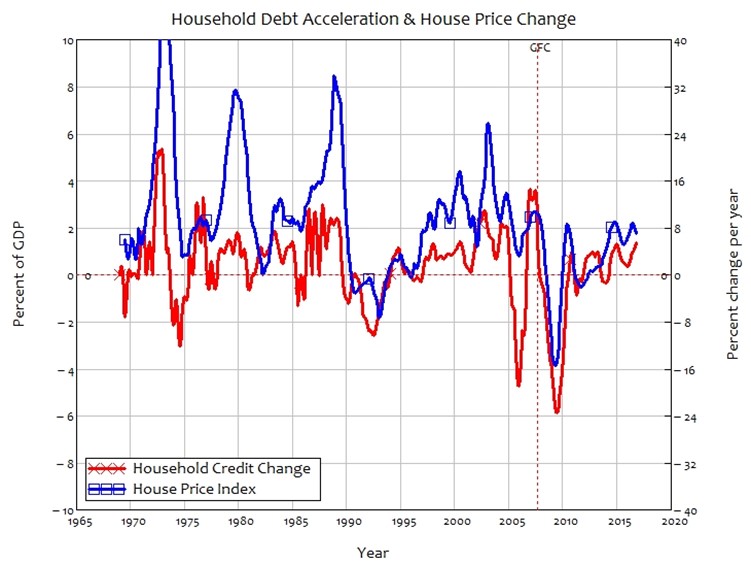

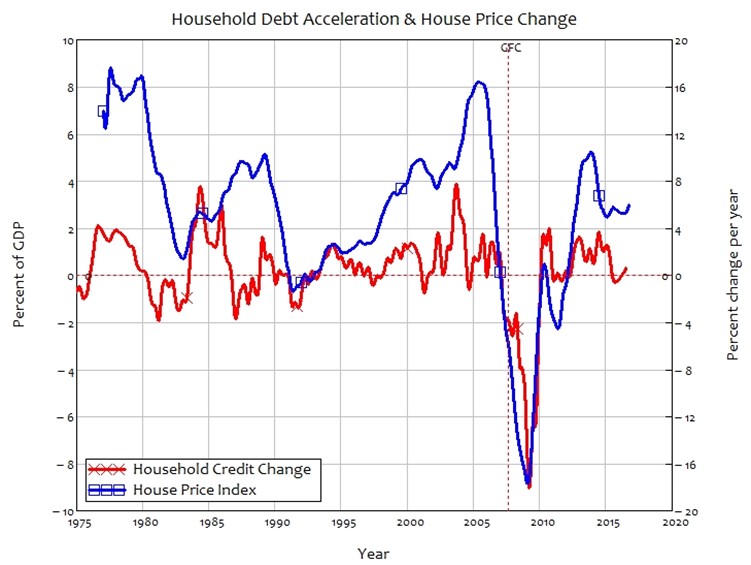

Change in Household Credit and Change in House Prices 178

Not Available

Not Available

Not Available

Not Available

Not Available

Not Available

Not Available

Not Available

Not Available

Not Available

Barro, R. J. (1973). “The Control of Politicians: An Economic Model.” Public Choice

14: 19-42.

Barro, R. J. (1978). “Comment from an Unreconstructed Ricardian.” Journal of Monetary Economics

4(3): 569-581.

Barro, R. J. (1989). “The Ricardian Approach to Budget Deficits.” Journal of Economic Perspectives

3(2): 37-54.

Barro, R. J. (1991). The Ricardian Model of Budget Deficits. Debt and the twin deficits debate. J. M. Rock, Mountain View, Calif.; London and Toronto:

Mayfield, Bristlecone Books: 133-148.

Bernanke, B. S. (2000). Essays on the Great Depression. Princeton, Princeton University Press.

Minsky, H. P. (1963). Can “It” Happen Again? Banking and Monetary Studies. D. Carson. Homewood, Illinois, Richard D. Irwin: 101-111.

Minsky, H. P. (1977). “The Financial Instability Hypothesis: An Interpretation of Keynes and an Alternative to ‘Standard’ Theory.” Nebraska Journal of Economics and Business

16(1): 5-16.

Minsky, H. P. (1978). “The Financial Instability Hypothesis: A Restatement.” Thames Papers in Political Economy

Autumn 1978.

Minsky, H. P. (1982). “Can ‘It’ Happen Again? A Reprise.” Challenge

25(3): 5-13.

Minsky, H. P. (1982). Can “it” happen again? : essays on instability and finance. Armonk, N.Y., M.E. Sharpe.