The Coronavirus was not caused by Climate Change: it obviously correlates with climate change, but “correlation is not causation”.

However, when two trends do correlate, one reason can be that they are both caused by the same underlying factor. In the cases of both Coronavirus and Climate Change, that factor is the load that industrialized humanity has placed upon the Earth’s biosphere.

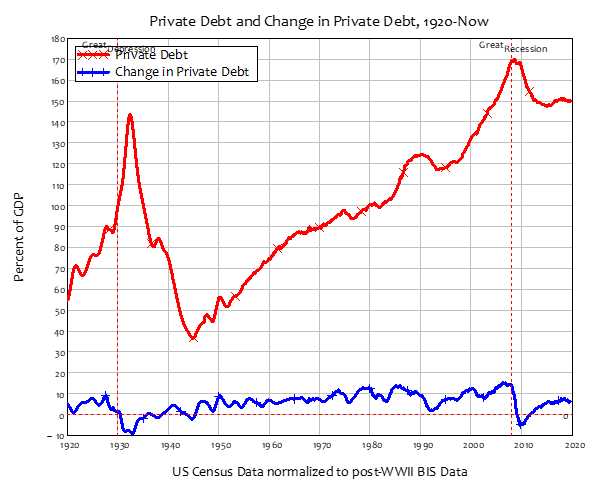

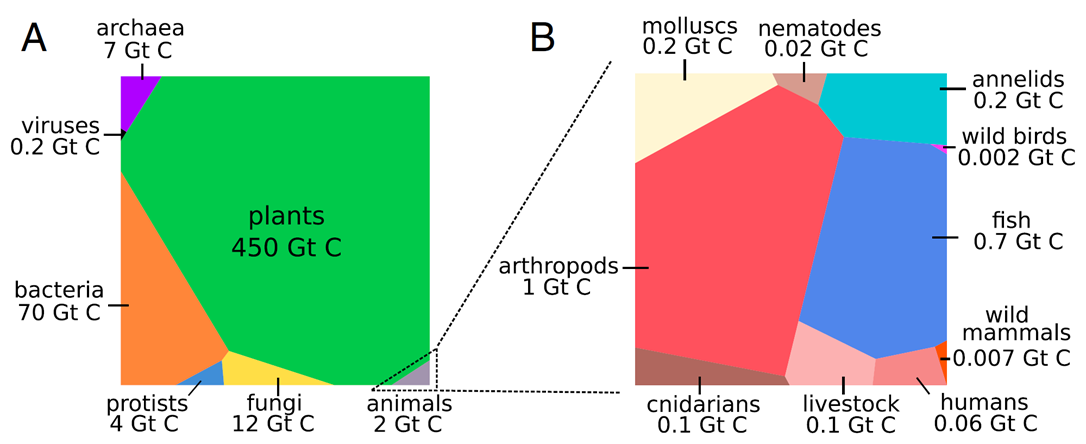

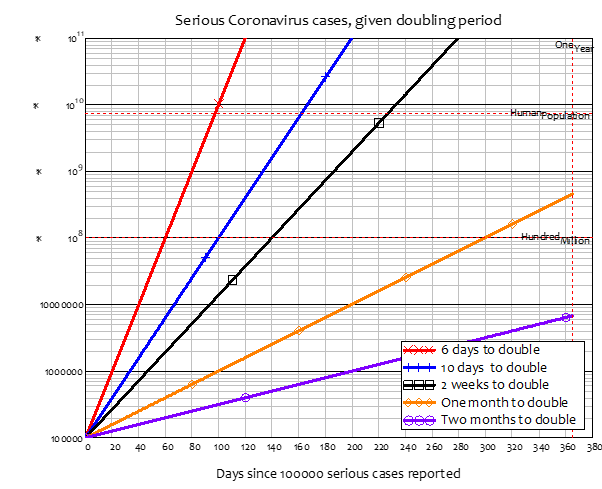

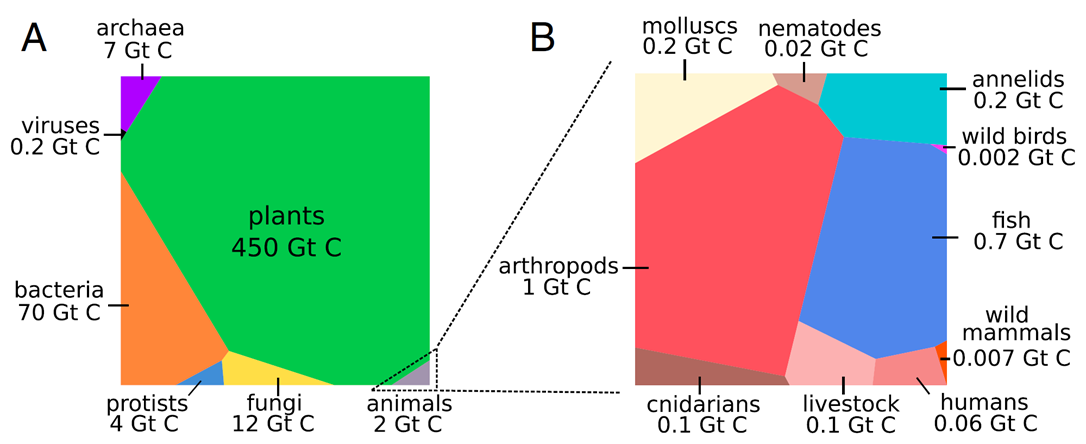

The stronger case for this can actually be made for the Coronavirus, rather than Climate Change. The academic paper “The biomass distribution on Earth” measured the relative mass of lifeforms (including viruses) on Earth, in terms of their carbon mass. It estimated that humans, at 0.06 Gigatonnes of carbon, represent almost ten times the mass of all wild mammals on Earth (0.007 Gt), while livestock are in turn almost 20 times the mass of humans (0.1 Gt: see Figure 1). Had an alien civilization done an audit of life on Earth like this 100,000 years ago, humans would have constituted only a tiny fraction of the roughly 0.1 Gigatonnes of mammals on this planet. Now, as it was summarized by one media outlet humans, and the animals we breed for our own use, constitute 96% of the mammal biomass of Planet Earth.

Figure 1: Biomass of lifeforms on Earth by Gigatonnes of Carbon

Several characteristics of humans that let us become the peak predator on this planet are key factors that have led to this crisis—and the many other crises that will follow it.

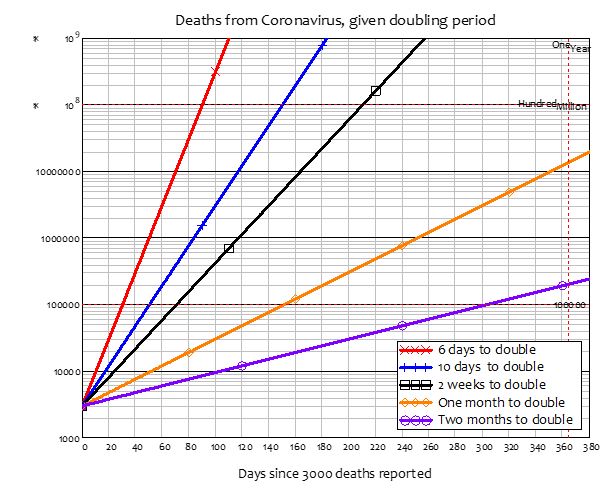

Because we are the peak predator, we (and our livestock) are also the best mammalian environment for pathogens. Any virus that infects a wild mammal peak predator—say a lion—will have a limited existence on Earth, because its host’s numbers are declining. Ours have been rising exponentially ever since industrialization, from under 1 billion in 1800 to over 7.5 billion today.

Unlike other predators, we are sociable between groups as well as within them (this sociability includes our wars, since the victors occupy the territory of the losers, and live amongst them). Lions are sociable within a pride, but not sociable between them (apart from a male killing the male and cubs of another pride, and taking over the females). A pathogen that infects one pride of lions is not highly likely to infect another. A pathogen that infects one group of humans is, on the other hand, highly likely to infect other groups.

Livestock are also sociable, so that a disease that springs up in one herd will spread through it—hence, for example, the death of something close to 50% of China’s pigs due to a swine fever last year. Livestock also constitute by far the biggest potential host for mammalian pathogens—which is one reason that many of our biggest diseases originate in chicken farms, pig farms, etc. But livestock are not mobile (of their own accord): they can’t move from one location to another if humans don’t want them to. It’s also easy to stamp out a pathogen in livestock by killing the herds that carry it—as was done with China’s swine fever outbreak in its pig farms.

We, on the other hand, are by far the most mobile, sociable species that has ever existed, and we don’t take kindly to killing our own kind—at least in comparison to how blithely we kill other species. So, what better environment could there be for pathogens to develop in than humans? A pathogen that infects humans will grow in numbers as our numbers grow, will spread thanks to our sociability, and will super spread thanks to our industrialized mobility.

In her brilliant 1994 book The Coming Plague, Laurie Garrett warned that it was only a matter of time before a successor to the Spanish Flu evolved, and wreaked havoc upon humanity. Garrett pointed out that pathogens evolve along two primary dimensions: transmissibility and virulence. Normally an increase in one dimension results in a decline in the other. But inevitably, a pathogen would evolve that was both more transmissible and more virulent.

The most dangerous combination is substantial transmissibility and moderate virulence. Substantial transmissibility lets a pathogen spread rapidly. Moderate lethality is more effective than high lethality, because with high lethality the pathogen can kill its host before it gets a change to be transmitted. Coronavirus hits this evolutionary sweet spot, with the additional dangerous characteristic that it can be spread by people who lack symptoms: simply avoiding people who are obviously sick is not a strategy to avoid Coronavirus. It is also inherently infectious: we have no acquired immunity to it as we have with influenza (the virus that Garrett expected would be the source of the next pandemic).

So the danger that Garrett anticipated a quarter of a century ago has come to pass. Had we designed our health and production systems to cope with the inevitable event, we would have:

- Increased the capacity of our health systems, and trained doctors and nurses in excess of underlying demand;

- Produced stocks of standard emergency equipment like masks and ventilators (Garrett anticipated, correctly, that The Coming Plague would be a respiratory illness);

- Made our economies as robust as possible to a health crisis, with short supply chains, and an emphasis upon local rather than globalized production;

- Established free—indeed, be-paid-to-be-tested—health monitoring systems, to ensure that we can easily identify disease carriers during a pandemic; and

- Extended our monetary systems to finance normal expenditure by the bulk of the population in the event of a pandemic.

Of course, we have done the exact opposite. We have instead:

- Reduced the capacity of our health systems to cope with even standard episodic health issues, in the belief that not spending on social infrastructure was “saving for a rainy day“;

- Designed an economic system in which production is focused in low-wage countries and exported to the rest of the world, via lengthy supply chains that involve as many as, for example, 43 countries in producing an iPhone; and

- Allowed the private sector to run up the highest level of corporate and household debt in history, which has made the financial sector both incredibly powerful and incredibly fragile at the same time.

Why? It’s primarily because politicians and bureaucrats, above all else, follow the advice of economists. When they listen to health professionals, it is within the context of a budget and a direction of social evolution set by economists. The advice of health professionals will help determine how the health budget is spent, but not how big that budget is, nor whether it is administered in a manner that helps or hinders our management of a pandemic.

This is because, when politicians are students, they don’t study epidemiology, or engineering, or even mathematics. Instead, if they study any analytic discipline at university, it is almost always economics. The UK in particular is dominated by politicians who have done the “Philosophy, Politics and Economics” degree at Oxford University, as this long read for the Guardian pointed out:

This training in economics makes politicians and bureaucrats incapable of understanding a crisis like this. They are, however, very susceptible to the advice of economists. They therefore enacted policies that reduced our capacity to cope with a pandemic, crafted systems of production and distribution that drastically amplified its damaging impact when it did arrive, and ridiculed warnings of people like Garrett as “alarmist” and “Malthusian”. For these reasons, Neoclassical economics itself bears a heavy responsibility for the severity of the coronavirus health and economic crisis.

Neoclassical economists will of course ridicule this claim. One thing I’ve learnt from fifty years of fighting these well-meaning but deluded bastards is that they’re great at taking credit when the economic system is doing well, but quick to deflect criticism by feigning impotence when a crisis actually arises. After it, they will merrily throw around their favourite explanation for why they couldn’t have seen it coming, that it was caused by an “exogenous shock”. Witness Ben Bernanke’s pronouncements before and after the Global Financial Crisis:

- Before it, Bernanke took credit (on behalf of both the economics profession and the Federal Reserve) for what he called the “Great Moderation”: “Recessions have become less frequent and milder, and quarter-to-quarter volatility in output and employment has declined significantly as well. The sources of the Great Moderation remain somewhat controversial, but as I have argued elsewhere, there is evidence for the view that improved control of inflation has contributed in important measure to this welcome change in the economy” (Bernanke 2004, “What Have We Learned Since October 1979?”);

- After it, he absolved “economic science” from any blame for the crisis: “Do these failures of standard macroeconomic models mean that they are irrelevant or at least significantly flawed? I think the answer is a qualified no. Economic models are useful only in the context for which they are designed. Most of the time, including during recessions, serious financial instability is not an issue. The standard models were designed for these non-crisis periods, and they have proven quite useful in that context. Notably, they were part of the intellectual framework that helped deliver low inflation and macroeconomic stability in most industrial countries during the two decades that began in the mid-1980s” (Bernanke 2010, “Implications of the Financial Crisis for Economics”).

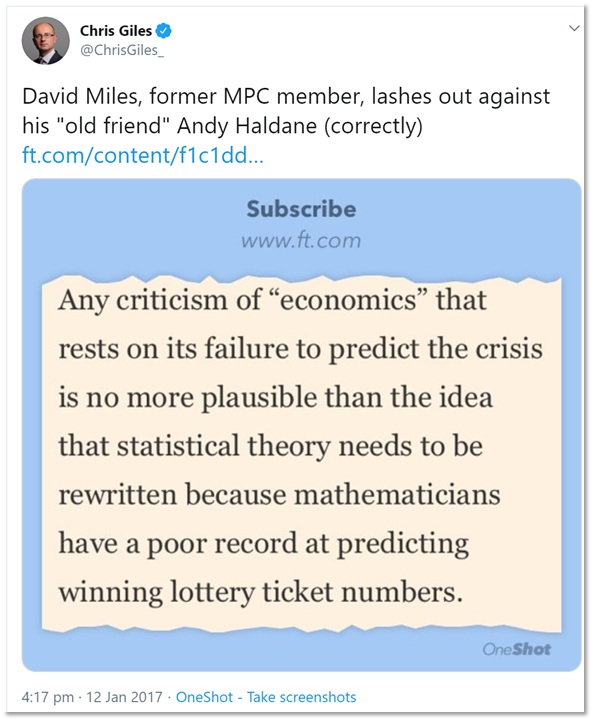

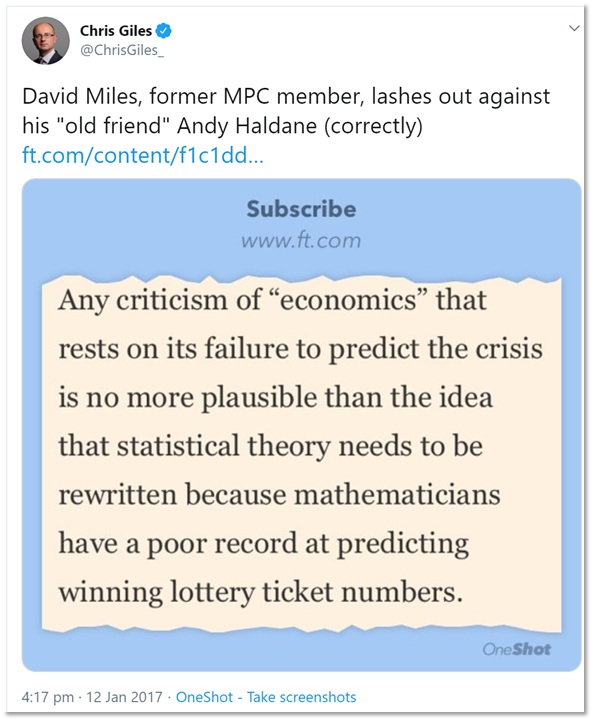

This isn’t because Neoclassical economists are inherently liars or weasels by the way: it’s because they have a paradigm that they sincerely believe does describe capitalism accurately, and as a result they can’t comprehend that in fact it doesn’t. So whenever their paradigm fails, as it did in 2007, they look for reasons why it didn’t really fail—such as that the crisis couldn’t have been predicted, and that criticizing them for not anticipating it was like criticizing a mathematician for not predicting next week’s winning Lotto numbers.

As I said in response to this comment at the time, this is Neoclassical bullshit. This is no different to a Ptolemaic astronomer telling Halley that he couldn’t predict the date of the return of the comet that bears his name, because in the Ptolemaic paradigm, comets were unpredictable atmospheric phenomena. As with Ptolemaic astronomers, it’s the Neoclassical paradigm that is at fault, and not the critics who reject it. **

So before they get up a head of obfuscating steam with respect to this crisis, let’s cut them off at the pass:

-

In the aftermath to this crisis—and possibly even during it—they will say that the influence of economics on policymakers is exaggerated: politicians took the decisions to cut medical funding and the like on their own accord.

- But if so, why did Paul Samuelson, the author of the most influential post-WWII economics textbook, and the true father of modern economics,*** state that “I don’t care who writes a nation’s laws—or crafts its advanced treaties—if I can write its economics textbooks“? He knew that the economic ideas of an age largely determine what its lawmakers and administrators do. His descendants today know likewise. The 1995 article linked to in this dot point describes the rise of Gregory Mankiw’s ubiquitous textbook, and states that he was the most promising of several “proselytizers” who “are jumping at the chance to mold the minds of the next generation of political leaders, executives, image makers and other members of the American elite“.

- This molding occurs primarily in the first year economics course that the vast majority of modern political leaders and bureaucrats take, in courses like Econ 101 in American universities, and in degree programs like Philosophy, Politics and Economics (“PPE”) in the UK. Mainstream economics is the main analytic tool they learn—very few learn mathematics, or engineering, let alone microbiology—and it’s the toolbox they first turn to when a new policy issue arises. ****

- Consequently, the perspective of all other disciplines doesn’t rate a mention compared to the impact of economics.

-

Economists will claim that it’s impossible to integrate all aspects of society into their analysis, so they have to make “simplifying assumptions” that, for example, omit the health system, population dynamics, and so on, from their underlying analysis.

- This has been false for sixty years, ever since the brilliant engineer Jay Forrester invented System Dynamics: a methodology to enable the analysis of multiple interlocking systems operating out of equilibrium, and having feedback effects on each other. This methodology still exists today, but it has received very little development support. Why? Because economists—and in this instance, particularly William Nordhaus, the recipient of the 2018 “Nobel Prize in Economics”—disparaged this methodology without understanding it in the first place. Economists, with their equilibrium methodology, continued to receive the lion’s share of funding, and system dynamics has wallowed along on trivial funding.

Economists cannot avoid responsibility for the fact that production is heavily globalized, both via the promotion by economists of free trade over self-sufficiency, and by their support for the relocation of production from the West to the Third World. Consequently, a disease like this hit the whole world when it hit just one country—though it helped that the one country initially was China, to which much of the world’s production was outsourced.

In the aftermath to this crisis, we have to revoke the carte blanche that economists were given to reshape the economy in the image of their textbooks. It’s time to let real sciences manage humanity’s impact upon this planet.

Footnotes

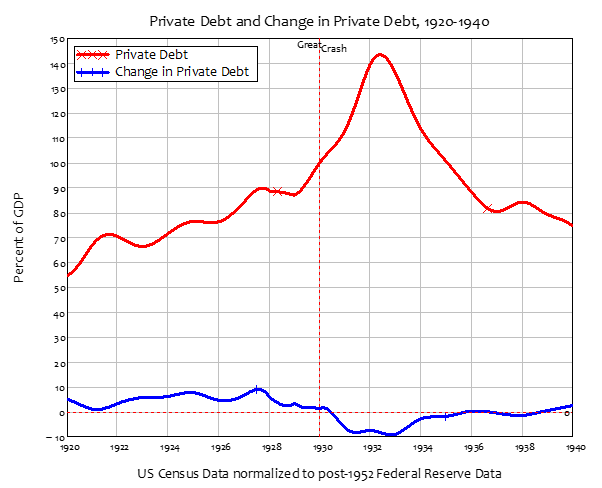

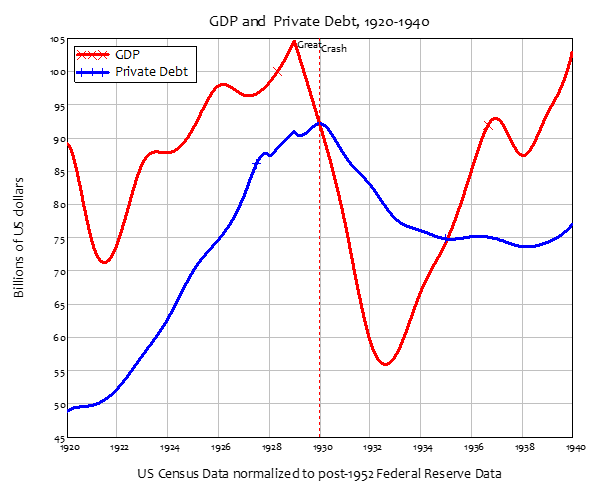

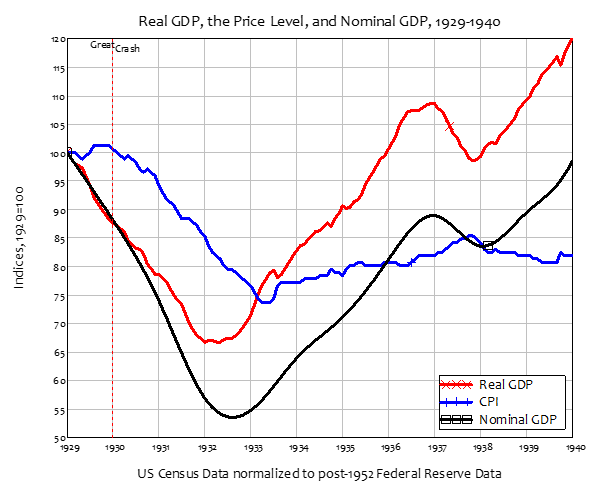

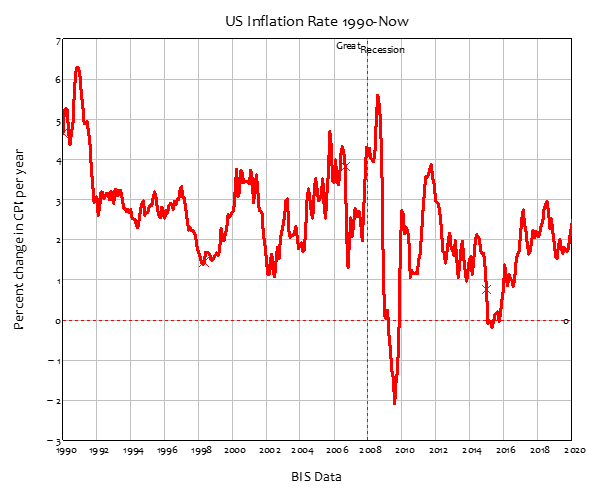

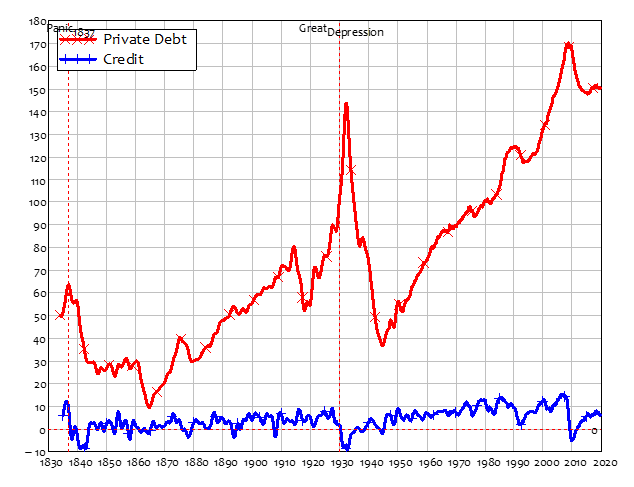

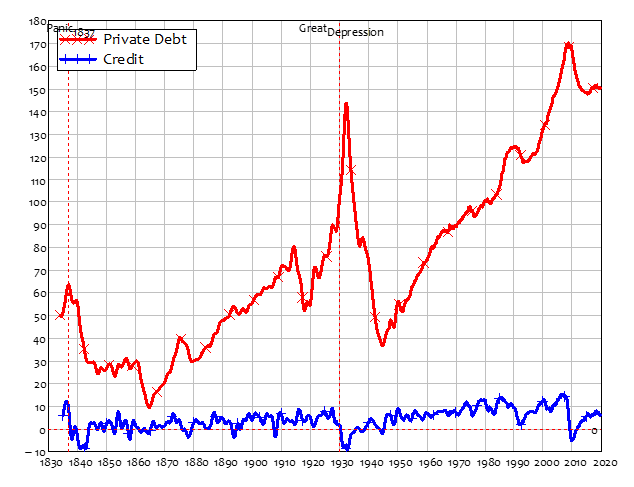

** There is an alternative paradigm (represented by people like the late Wynne Godley, as well as by myself, Michael Hudson, Ann Pettifor, Dirk Bezemer, and several others) in which private debt and its annual rate of change (which I call credit) play a pivotal role in macroeconomics, and their made a crisis inevitable. That’s what actually happened, but because private debt and credit play no role in the Neoclassical paradigm, they continue ignoring data about it. This is not because the data is not available, or is not compelling, but because it simply does not fit into their way of thinking about the world. So they ignore data which shows that every America’s three major crises were driven by a collapse in credit:

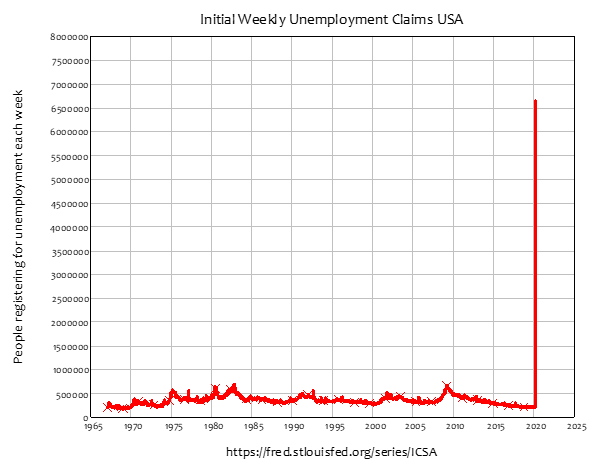

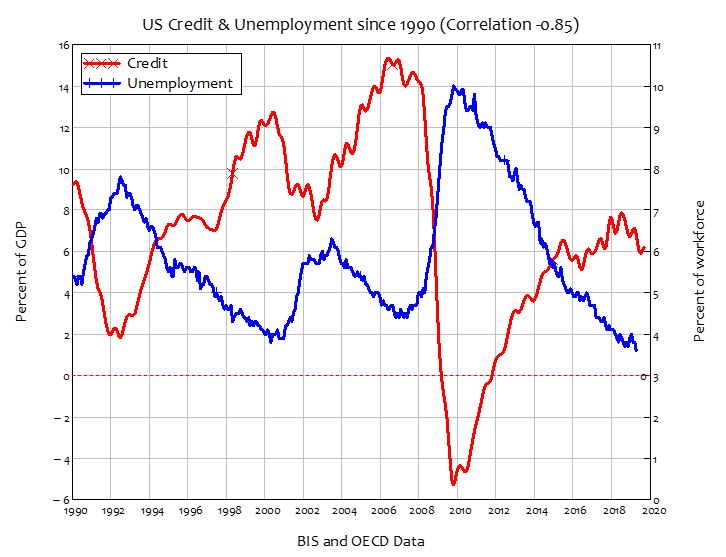

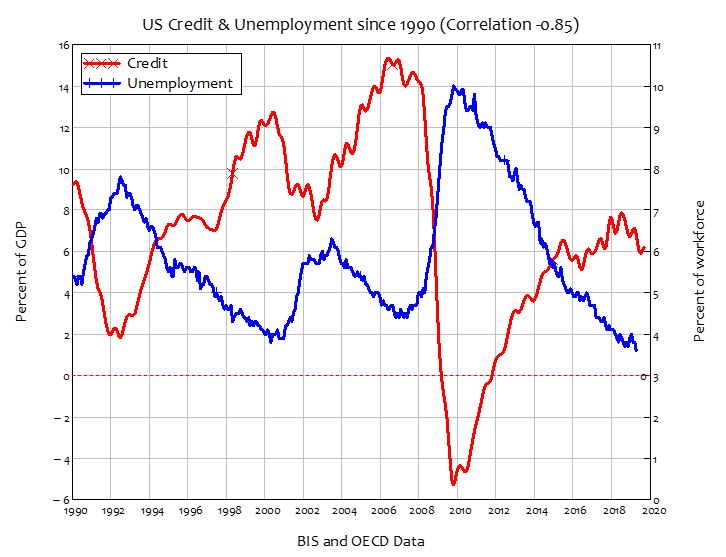

And they ignore the overwhelming correlation between credit and unemployment:

*** Both strands of mainstream macroeconomics—the so-called “New Classicals”, who are extreme free-market advocates and bear no resemblance to the actual Classical school of economic thought, and the so-called “New Keynesians”, who are moderate free-market advocates and bear no resemblance to the original ideas of Keynes—use the analytic tools that Samuelson invented, to generate what he called the “Neoclassical-Keynesian Synthesis“. What uninformed critics disparage as “Keynesian economics” should really be called “Samuelsonian Economics”.

**** A colleague of mine—the historian Chris Shiels, who wrote a brilliant critique of water privatisation in Australia called Water’s Fall—used to work in the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet when Paul Keating was Australia’s Prime Minister. He described how there would be panic amongst the staff at some new issue, which would only dissipate when someone suggested an approach that could be found in a first year economics textbook. Since almost all the advisors shared that paradigm, the idea would be readily adopted.

and

and  in the model:

in the model: